Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

In this edition, leaping from the week’s biggest story back in time…

PRIVATE PARTY

On Wednesday, news broke that the powerhouse collection of late financier and former Museum of Modern Art board president Donald Marron would not, in fact, supercharge this year’s auctions as expected. Instead, a gallery-sector triumvirate of Pace, Gagosian, and Acquavella will team up to sell Marron’s roughly 300 works, which collectively carry an estimated value in the neighborhood of $450 million, entirely on the private market. But while the collaboration is newsworthy and novel in certain ways, we’re fooling ourselves if we treat it as an unprecedented paradigm shift in the trade.

Granted, I’m more jaded than most when it comes to… well, practically everything, I guess, but especially the disintegrating boundary between major auction houses and major galleries. The theme was a pillar of the book I wrote in 2017, the cover story I wrote for the Artnet Intelligence Report last fall, and an undoubtedly annoying number of one-off pieces I’ve put out before, between, and after those milestones.

That doesn’t mean I wasn’t still surprised when I heard Marron’s widow, Catherine, and his other executors chose to bypass the Big Three auction houses for three big galleries. It just means that I got over the initial jolt pretty quickly, and that the finer points seemed downright intuitive once they emerged.

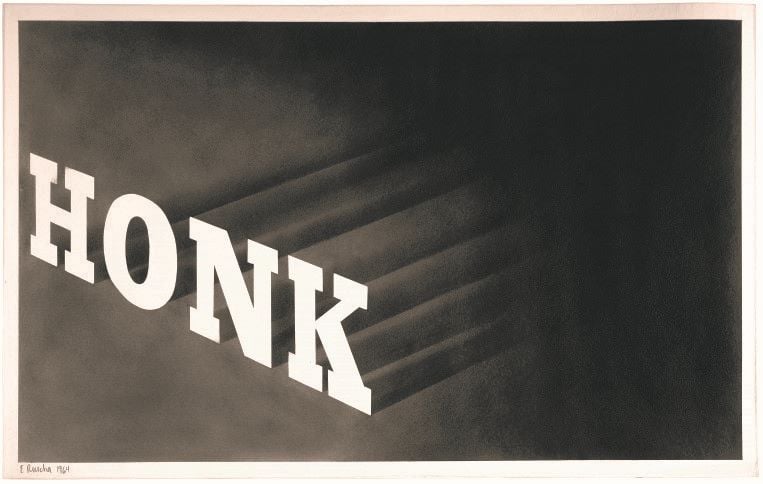

From left to right: Arne Glimcher, Bill Acquavella, Larry Gagosian, and Marc Glimcher ©Axel Depuex.

A few of those finer points are worth mentioning here for context’s sake. From April 24 to May 16, Pace and Gagosian will present a joint exhibition in their Chelsea spaces of highlights from Marron’s collection, such as Pablo Picasso’s Woman With Beret and Collar (1937) and Mark Rothko’s Number 22 (Reds) (1957), supplemented by select works loaned from institutions.

According to Marc Glimcher, the primary architect of the alliance, not every work in Marron’s collection will be for sale. (Personally, I don’t buy this notion for a second, but that’s the party line.) Eleanor Acquavella also verified that the troika sealed the deal in part by paying Marron’s estate an up-front financial guarantee of an undisclosed amount. (The Wall Street Journal reported that Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips had offered guarantees in the range of $300 million, so it’s safe to consider that figure a reasonable target.)

Last but not least, the galleries will work with premier publisher Phaidon to produce a lush book on the collection, not a crass auction-style “catalogue” with prices, as Glimcher emphasized to my colleague Eileen Kinsella.

Similarly, he told the WSJ that asking prices will only be publicized for works in the exhibition that are still unsold upon its opening. Because most, if not all, of the pieces are expected to find buyers in advance, most, if not all, of the prices will be known strictly to the galleries, the estate, and the necessary financial intermediaries.

All told, the plan has all the high-end elements and private-sale obfuscations I’d expect from a co-production by Pagavella. (Yes, I just Brangelina’d Pace, Gagosian, and Acquavella. Hit me with a steel chair.)

But the most remarkable aspect here isn’t necessarily that these cogs all came together. It’s that they came together in part because some of the galleries involved had connected several of them decades earlier.

Ileanna Sonnabend at her gallery in Paris in 1965. Image courtesy of the Sonnabend Collection Foundation. ©SOCAN (2019).

BLAST(S) FROM THE PAST

In her Wall Street Journal story on the Marron alliance, Kelly Crow briefly raises the most recent precedent: the 2008 private sale of artworks worth hundreds of millions of dollars owned by the late, great dealer Ileana Sonnabend. Larry Gagosian was a key part of that pact, too. And it’s worth sussing out how it compares to the Pagavella team-up to get a sense of what has (and hasn’t) changed over the years.

Antonio Homem, one of Sonnabend’s two heirs, told Carol Vogel of the New York Times in April 2008 that the estate had agreed to sell “two blocks of works” with a staggering combined estimated value of $600 million (about $720 million today, if you adjust for inflation). That’s well over the $450 million estimate for Marron’s holdings.

The first “block” of Sonnabend works, totaling roughly $400 million (and including Jeff Koons’s later-to-be-record-smashing Rabbit), was acquired by GPS Partners—the dealer trio of Franck Giraud, Lionel Pissarro, and Philippe Ségalot. Although Vogel reported the transaction came “on behalf of several clients,” art-market opinion has since solidified around the notion that most, or all, of the works were part of a historic spending spree by the Qatar Museums Authority, which both Giraud and Ségalot worked with closely for years.

The second “block” of works, comprising the remaining $200 million and consisting entirely of Andy Warhols, went to Gagosian. He was simply said to be “representing several American and Russian collectors in the deal,” which could mean literally anything.

What we can say for sure, though, is that Sonnabend’s collection was nowhere near cleaned out even after these two mass sales. Several more works mounted the auction block at Christie’s in 2015 via the estate of her daughter, Nina Castelli Sundell. The Sonnabend Collection Foundation (now run by Homem) also just staged an exhibition of more than 100 pieces at Canadian institution Remai Modern last fall.

From left: Arne Glimcher (Gary Gershoff/WireImage) and Marc Glimcher (Kris Graves, courtesy Pace Gallery).

Another antecedent to the Marron deal also warrants resurrection. In 1995, PaceWildenstein shocked the art market by winning the rights to sell the collection of late TV producer Mark Goodson—a trove of roughly 50 Modern masterpieces by the likes of Picasso, Francis Bacon, and Wassily Kandinsky. The face of the deal? Marc Glimcher’s dad, Arne Glimcher.

At the time, the elder Glimcher projected the Goodson holdings to be worth more than $40 million (about $68 million today). While the size of both the collection and the valuation pales in comparison to Marron’s, other aspects of the Goodson pact loudly echo elements of Pagavella’s new arrangement.

Most notably, PaceWildenstein mounted a dedicated exhibition simply titled “The Mark Goodson Collection,” from October 27 through November 25, 1995, at its New York headquarters on 57th Street. Goodson had acquired many of his works from Glimcher in life—just as Marron built his collection largely through Pace, Gagosian, and Acquavella—making it similarly organic for the same dealer(s) to handle them in death.

There was also speculation that PaceWildenstein had offered Goodson’s executors a financial guarantee. But Glimcher refused to discuss the matter with Vogel of the Times, who noted that “art experts close to PaceWildenstein [said] that the estate was not interested in such financing deals.”

Glimcher did shed light on his gallery’s sales pitch to Goodson’s estate… and it largely matches the one his son, Gagosian, and the Acquavellas used to secure the Marron consignment 25 years later. Unsold works would not be “burned” by failing in public, and pieces could be sold more judiciously over time instead of being lumped into one high-stakes evening auction.

He also argued that PaceWildenstein could exhibit and tour Goodson’s works across its network of permanent spaces—then spanning New York, Los Angeles, and London—even more effectively than the auction houses. Although the Pagavella alliance hasn’t mentioned this point to the press regarding the Marron estate, I’d be surprised if it didn’t come up during negotiations.

The more things change, the more they stay the same, right?

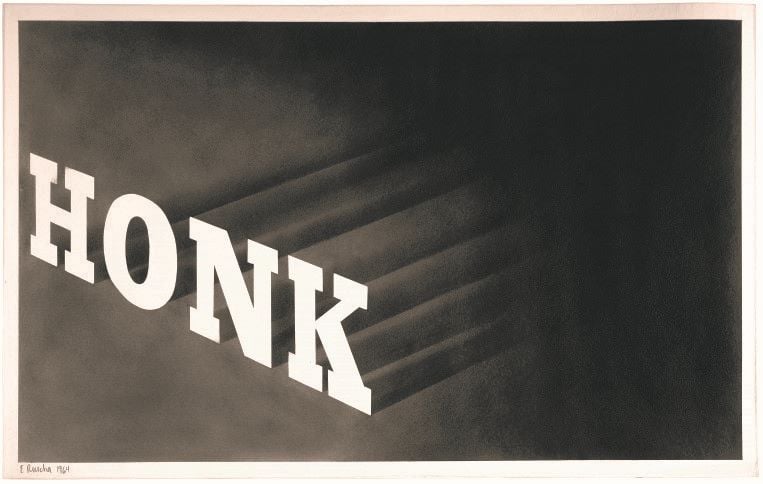

Ed Ruscha, Honk (1964) ©Ed Ruscha. Courtesy the Donald B. Marron Family Collection, Acquavella Galleries, Gagosian, and Pace Gallery.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Overall, then, Pace, Gagosian, and Acquavella’s arrangement with the Marron estate looks less like an art-market sea change and more like a natural progression from these two past landmarks. The Marron collection’s scope and value at least approach what we saw in the Sonnabend private sale, and the decision to hold a gallery exhibition of the works mirrors what PaceWildenstein did with the Goodson estate.

And while it was never stated that GPS Partners and Gagosian struck an official alliance regarding the Sonnabend works, the idea that these high-powered dealers didn’t coordinate closely (and likely argue hard) to divvy up the inventory seems about as dubious to me as ordering shellfish at a midwestern truck stop.

The financial guarantee made to the Marron estate lands in a gray area between the two private-estate-sale precedents. Even if we take Carol Vogel’s sources at their word that PaceWildenstein didn’t provide a set sum for the Goodson collection, you could argue that the Sonnabend private sale effectively worked as a guarantee since it was carried out as two massive up-front transactions that the dealers then had to carry forward into individual deals, each one vulnerable to second thoughts or bad behavior on the buyer’s side. (Remember: it’s not a deal until the check clears.)

In this sense, it could be said that the only true novelties of the Marron deal are the collaboration of three different mega-dealers instead of two… and the production of a great book on the collection.

I’m not saying those aren’t consequential, or that the estate’s choice to go private doesn’t wallop the Big Three auction houses with the force of an anvil dropping onto a trio of unsuspecting cartoon cats. I’m just saying that, when you consider that a quarter century has passed since PaceWildenstein’s agreement with the Goodson estate, it doesn’t exactly feel like a quantum leap in art-market innovation.

Let’s also keep in mind that even the public auction market now functions much more like the gallery market than ever. As Allan Schwartzman has pointed out, the real competition now tends to happen in private before the public sales, when buyers with swollen pockets jockey for the right to guarantee major works in the first place—a scenario that explains why upper-echelon lots often spur much less bidding in the room than they used to. So why not skip the gavel and go straight to the galleries, especially if they can now hand you just as rich a guarantee as Christie’s or Sotheby’s?

I don’t know if that was part of the Marron executors’ calculus when they accepted Pagavella’s collaborative offer. But I do think it makes a lot of sense for both sides of the deal.

All the more reason we shouldn’t be floored when another major estate goes the private-dealer route in the years ahead. Proof of concept has already been in plain sight since the ‘90s—and as more money and power gravitates to the apex of the gallery sector, the pitch is only going to become more persuasive.

[Artnet News]

That’s it for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Silicon Valley will tell you the best way to predict the future is to invent it… but being a geek about the past is a pretty decent strategy, too.