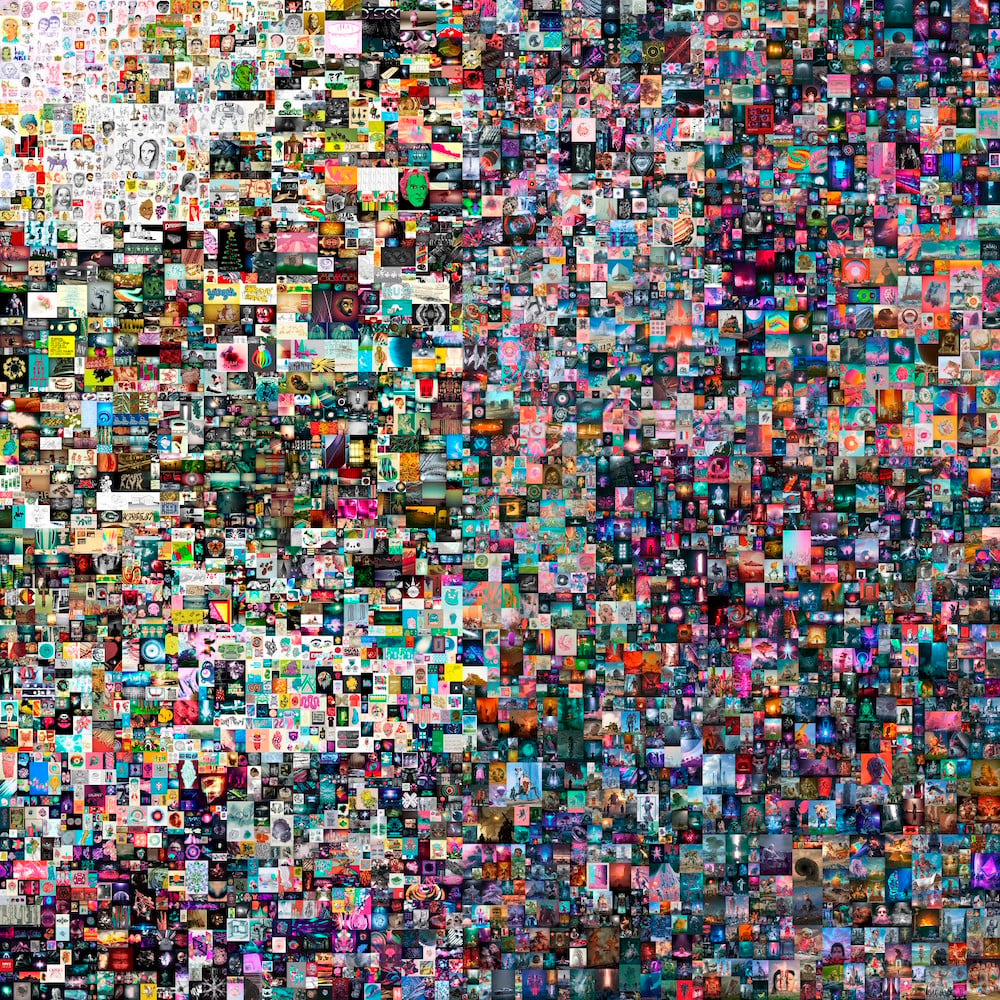

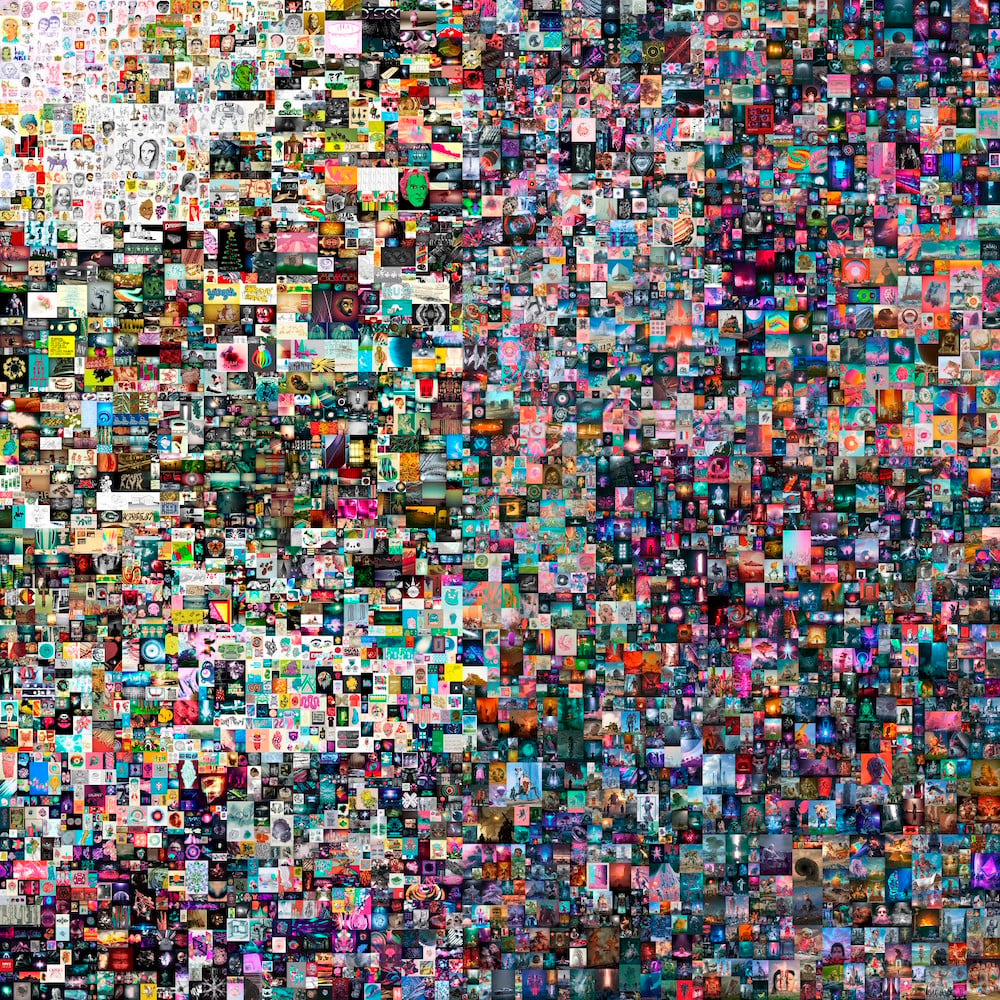

After a year of hibernation, the art market is making up for lost time. But dealers, collectors, and artists are reemerging into a changed landscape after the NFT upstart Beeple sold his opus Everydays: The First 5,000 Days at Christie’s in March for $69.3 million—the third highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist at auction.

Against the backdrop of this NFT market frenzy (not to mention other record auction sales), we would do well to remember an unresolved case that gripped the art world before the pandemic. Its lesson: greed will push the art market off the rails—but making sure the market works for artists can get it back on track.

Beeple, Everydays – The First 5000 Days NFT, 21,069 pixels x 21,069 pixels (316,939,910 bytes). Image courtesy the artist and Christie’s.

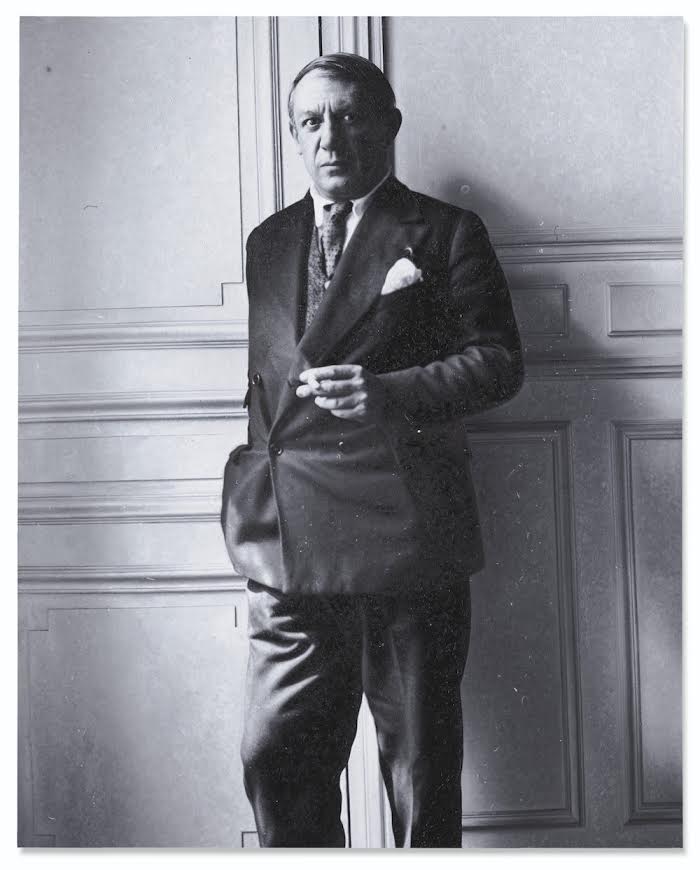

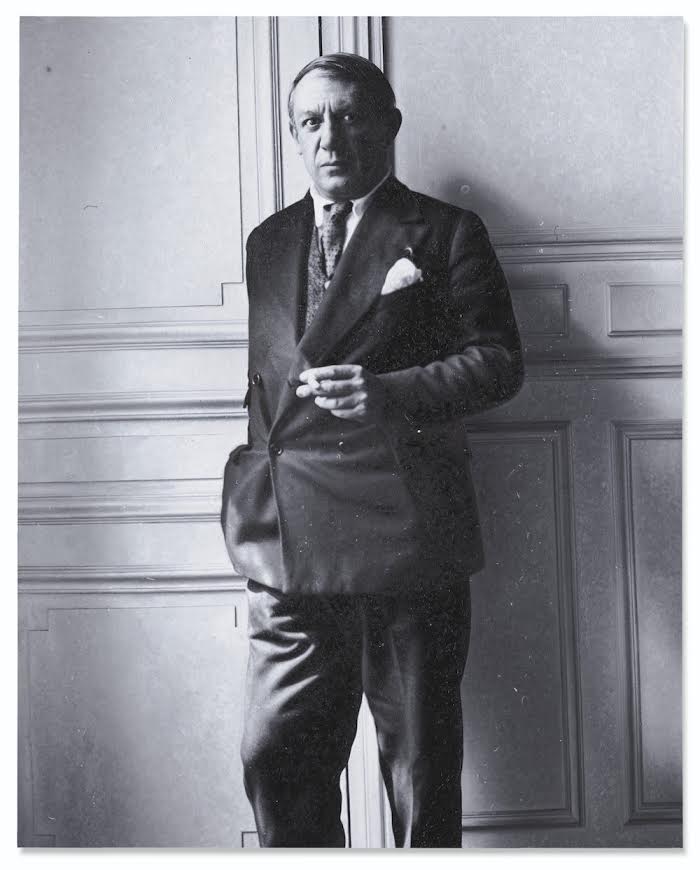

In June 2020, Inigo Philbrick, who had run an eponymous gallery in London, was arrested by U.S. federal agents on the Pacific island of Vanuatu. A sealed complaint brought by the Southern District of New York charged him with wire fraud and aggravated identity theft stemming from “false and fraudulent” art sales contracts.

According to the complaint, Philbrick “knowingly and willfully misrepresented the ownership of certain artworks […] by selling a total of more than 100 percent ownership in an artwork to multiple individuals and entities without their knowledge.” Claiming to use the oversold shares as loan collateral, Philbrick took an Icarus-like fall when his co-investors found out they didn’t actually own the artworks they thought they’d bought.

As we write in a paper published last week, the case sent shockwaves through the art market. At $20 million, the estimated total of Philbrick’s supposed fraudulent scheme is a fraction of other recent art fraud cases, like the one that engulfed Knoedler Gallery or Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier.

Inigo Philbrick © Patrick McMullan. Photo by Liam McMullan / PMC

Philbrick’s case is instructive not because it is the most extreme, but because some of his tactics—like the use of offshore entities and shell corporations in art-financing deals—are still widely exercised in the art market. And as the art world comes out of the pandemic and metabolizes the non-fungible token phenomenon, the Philbrick affair has something to teach us about the governance of the art market, the ways we form trust in systems, and the ways we might reform this one.

Lessons From Philbrick

Philbrick’s crime of financialization is only possible because of the norms of opacity in the art market. Art collectors and speculators alike place trust in dealers as people. Although there’s enormous development toward anti-fraud regulation, including the U.K.’s recent buyer transparency requirement, the art market does not yet generally have widespread, trusted registries for purchase such as those that have been proposed using blockchain technology.

This opacity ends up harming the characters who are missing in the Philbrick story: the artists. Artists are the primary citizens of the art market and also the starting point for the ways we might meaningfully reinvent art-market governance.

There are two different factors in the auction and resale market, where Philbrick was operating, that affect artists. The first is whether they get a percentage of the resale proceeds. The majority of artists do not benefit when their work sells at auction. Although artists receive modest resale royalties in some countries (but generally not in the U.S.), they are more often structurally cut out of the financial gains, receiving only a modest initial payment even if their works later soar in value.

An untitled Rudolf Stingel from 2012 at the cente of the Philbrick case. Image courtesy Christie’s.

The second factor is speculation—which, as in the Philbrick case, can destabilize an artist’s overall market by causing their works to sell for erratic prices. In an industry in which many gallerists view their job as managing their ascendant artists’ prices, a Philbrick scandal is analogous to an exogenous shock.

Of course, Philbrick didn’t introduce these inequities. But the market interest in non-fungible tokens can either point to more Philbrick scandals and greater inequity, or to an artist-centric future of collective ownership and shared upside.

Are NFTs the Problem or the Answer?

NFTs—typically digital artworks registered to the blockchain via a token that functions as a certificate of authenticity—allow digital objects to present as originals. NFTs make certain kinds of artworks newly investible—especially digital works that theoretically exist in infinitely replicable copies.

The big NFT sales—like the record Beeple—mask the important efforts by artists to build equitable market systems. Artists on SuperRare and Feral File receive a percentage share when their works resell. On these and similar platforms, the fact that the shares transfer via blockchain can help avoid a Philbrick-type scandal because 100 percent of the artwork must be accounted for. In this way, NFT structures and blockchain registration can stabilize and prevent fraud without relying on middlemen like Philbrick, who didn’t actually represent artists but only traded their works.

Maya Man, can I go where you go (2021). Image courtesy Feral File.

Artists are also using NFT structures to band together to share risk. In Kelani Nichole’s NFT sale through Transfer Gallery, artists who sold work received 70 percent of the proceeds and shared 30 percent across all of the artists in the show. Artists in a Feral File exhibition receive a copy of every other artwork in the show, so if one succeeds, the other artists can participate in the upside.

Still other artists are using NFT-type structures to redistribute proceeds. Sara Ludy, who is represented by Bitforms Gallery, started designating 35 percent of the proceeds from her NFT sales to her gallery, 50 percent to herself, and 15 percent to the crypto platform she decides to sell with. Of the 35 percent to Bitforms, one 7 percent share goes to the gallery owner and the other 7 percent shares go to the individual art workers employed by the gallery.

As the art world moves out of the pandemic, Philbrick should be an enduring reminder that the art market is a democracy of which artists are the citizens, and the rest of us benefit when we treat them that way and try to think like artists ourselves.

In an age of fake news, real inequities, and the difficulty of imagining the future, the artist-citizen is the antidote to this new kind of art market scandal. Adopting the mindset of the artist-citizen can teach all of us to navigate the risks of financialization and protect the things that matter to us most.

Amy Whitaker is assistant professor of visual arts administration at New York University and is the author of Art Thinking and the forthcoming Economics of Visual Art.

Fiona Greenland is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Virginia and published Ruling Culture: Art Police, Tomb Robbers, and the Rise of Cultural Power in Italy earlier this year.