Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, asking a natural follow-up question about an art year in flux…

MOVE IT OR LOSE IT

Starting last Wednesday—only hours after the World Health Organization declared the novel 2019 coronavirus a global pandemic—a tidal wave of museum and gallery closures, art-fair postponements, and auction-sale delays began surging across the Western art world in response to the growing public-health crisis. And although the reopening of select art institutions in East and Southeast Asia on Friday provided a jolt of optimism to art lovers and the nonprofit side of the industry, the reality on the for-profit side is that COVID-19’s temporary reshuffling of events could also permanently reshape the art-market calendar in the years ahead.

If you haven’t been tracking the minute-by-minute changes, here’s just one small sample of what the virus triggered in the art market between Wednesday morning and Saturday night:

- TEFAF Maastricht ended four days early after an exhibitor tested positive for COVID-19.

- Pace, Gagosian, and Acquavella announced the postponement of their joint exhibition of the $450 million collection of Donald Marron, shortly before seemingly every gallery in New York (including all Pace and Gagosian locations in the city) shut down until further notice.

- Four major spring art fairs on three continents, including Art Cologne and the inaugural edition of Paris Photo New York, moved their opening dates either to the fall or another time yet to be announced.

- Christie’s postponed 14 spring sales (so far excluding its major May auctions in New York) and closed down 26 of its locations worldwide, leaving only its King Street venue in London operating at full capacity.

- Phillips delayed all sales in the US and Europe through mid-May, including the premier 20th-century and contemporary auctions it would have held during May auction week in New York. All physical locations in the US and Europe are also vacant until further notice.

Aside from their largely high-profile nature, the examples above capture one of the most important points about the (much) larger list of changes to the 2020 schedule: “postponed” is the magic word. Only a small number of art-market players have admitted defeat by outright cancelling key events.

And who can blame the organizers? Every business owner has a responsibility to try to adapt to market conditions, and almost every human being has an urge to try to maintain as much normalcy as possible in unsettling times.

However, it seems highly unlikely to me that the art market can effectively transfer a full quarter’s worth of sales and trade fairs into the back half of the year without a significant amount of cannibalism taking place. (To be clear, I’m strictly talking about metaphorical cannibalism. Things aren’t that bleak yet.) And the reason why has been staring us in the face like a creepy train passenger for years.

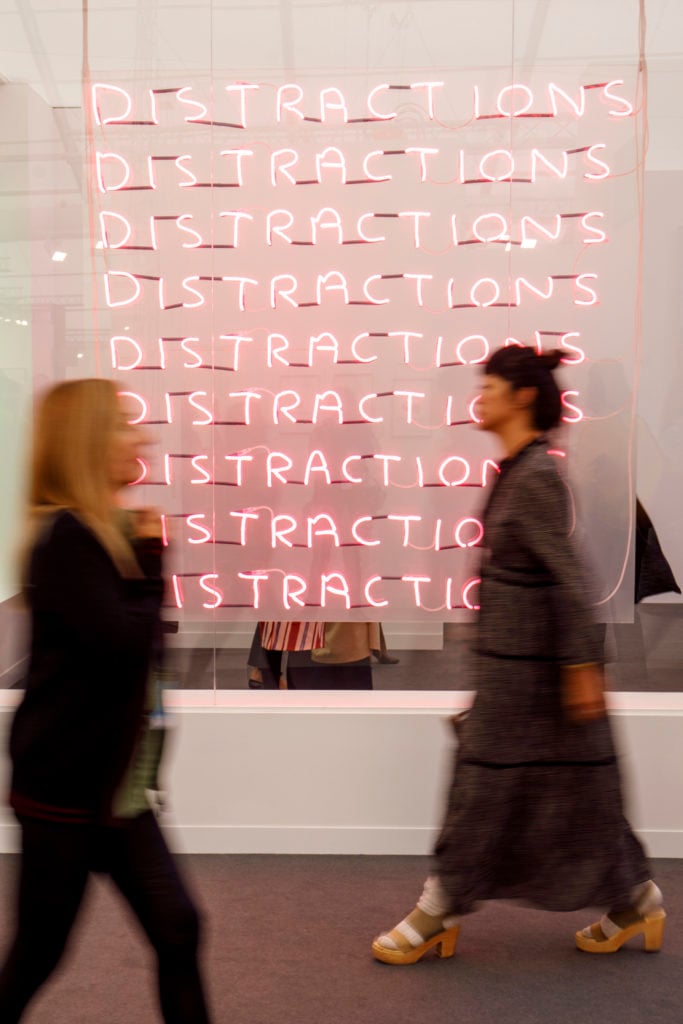

David Shrigley’s Distractions at Frieze 2018. (Photo: TOLGA AKMEN/AFP/Getty Images)

BALANCING ACT

One common refrain you’ll hear about crises is that they inevitably reveal the structural flaws in the underlying systems they affect. Demand incentivizes realtors to price beachfront property as an aspirational luxury until climate change threatens to obliterate entire coastlines. Bankers beat their chests about the virtues of radical self-reliance until a global financial crisis wrought by some of their own actions sends them to the federal government begging for a gargantuan publicly funded bailout. The examples are almost endless.

True to form, the coronavirus is unearthing all kinds of foundational problems in government and industry alike. The art economy is most definitely among those whose vulnerabilities are getting exposed, and perhaps one of the most obvious is the potentially unsustainable bloat of the art-market calendar.

Many, if not most, people involved in the industry have agreed for at least the past couple of years that the lineup of annual events has gotten too packed, too frenzied, too all-consuming for anyone’s good. We all know the numbers by now: somewhere between 200 and 300 yearly art fairs; thousands of live and online auctions (Sotheby’s alone held over 400 combined sales in 2019); dozens of biennials, triennials, quinquennials, and seemingly every other -ennial you can imagine; plus, an almost-incalculable glut of gallery openings.

Put it all together, and the visual that keeps popping into my head is that of Red Panda, the acrobat who wows audiences during halftime at NBA games by kick-flipping ceramic bowls into a stack on top of her head while simultaneously riding a giant unicycle. In other words, the sheer amount of activity in a typical art year means that even a modest shock to the system can upend the entire spectacle.

Events cancelled outright are a micro problem—a blow to the people and businesses directly involved, but not a macro problem that radiates out to the rest of the calendar. And while the logistics would no doubt be difficult, it would probably still be possible for a handful of postponed events to find a safe haven later in the year without encroaching on others in the field.

However, the coronavirus has now pushed the balance hopelessly out of whack for 2020. Too many events have already been knocked out of their respective positions in the spring, and too few of them have thrown in the proverbial towel. It sounds fine in principle for the dozens of art-market events scheduled for March, April, and now early May to push back a few months. But where are they all going to go, exactly?

Sure, August is mostly open, but that’s because it’s the only month on the art-world calendar designated for something resembling leisure. How successful is an event going to be if it has to ask its clientele to diminish their Hamptons or St. Barths time? And good luck finding an opportune makeup moment in the fall art season, which is already packed-to-bursting with its own slate of gallery openings, fairs, and auctions. The center can no longer hold.

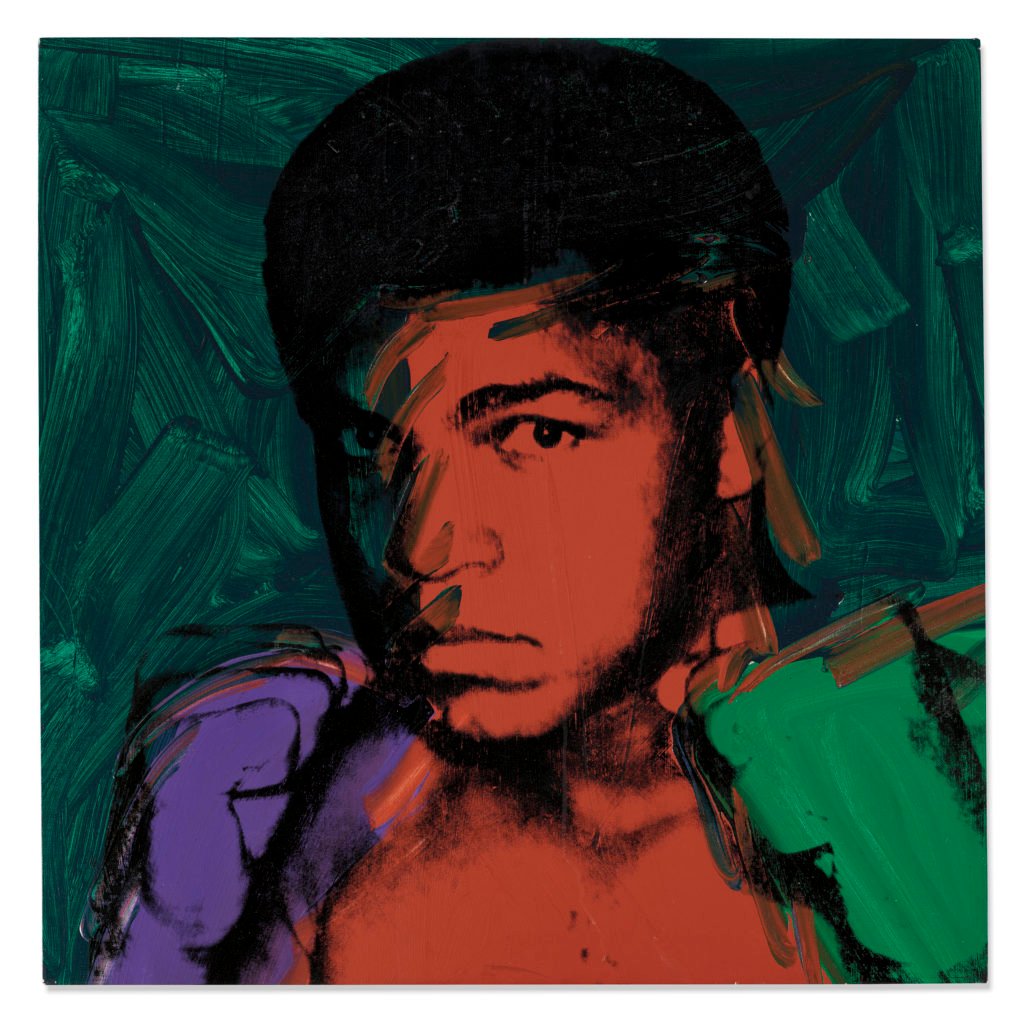

Andy Warhol, Muhammad Ali (1977). Courtesy of Christie’s.

KNOCK-DOWN, DRAG-OUT

All of the above leads me back to my comment about art-market cannibalism. As much as dealers, fair organizers, and auction houses will want to—or at least want to look like—they’re playing nice with one another in the aftermath of this crisis, their respective leaders all know that they can’t bend the space-time continuum to allow buyers, curators, and even the dealers themselves to be in multiple places at once with the best works on hand. Direct conflicts are going to arise.

Those conflicts will force people to make hard choices, and those choices will in turn take events with favorable odds for success when they were able to occupy their own slice of turf and turn them into losers when they’re forced to go head-to-head (or close enough) with competitors normally ensconced in other parts of the year.

I think this clash would play out even if buyers ultimately wrote just as many checks after the coronavirus fiasco as they would have in a pandemic-free year. But that scenario seems unlikely to me, too. Again, all signs point to COVID-19 triggering a global recession—a circumstance in which discretionary spending on items like artwork tends to tighten up dramatically. Combine more cautious buyers with an overabundance of available works resulting from so many spring events shifting to fall, and the supply-versus-demand dynamic tips into worrisome territory for almost everyone on the sell side.

I suspect the stakes are especially high for many (but not all) regional fairs. Assuming they won’t have to refund gobs of cash to exhibitors if their 2020 editions go forward at later dates—not a guarantee, depending on the tortuous specifics of insurance policies and exhibitor contracts—the situation will get especially dire if galleries use the recession as either an easy excuse, or a truthful basis, for opting out of returning to smaller fairs where results have been middling (or worse) for multiple editions.

After all, many dealers have been openly talking about their intent to cut back on their annual booth count for some time. What better motivation is there to finally do it than a financial crisis? Even more sobering, how many galleries won’t manage to survive the months between the original and rescheduled dates of fairs at which they’ve agreed to show, let alone endure long enough to pay the fees to take part in next year’s edition?

In the end, then, postponements may not save several art-market events whose prospects were already looking a bit shaky in a consolidating field. So when the dust settles on the coronavirus catastrophe, I expect it will leave near-future annual calendars in the industry sparser than the ones we’ve grown accustomed to. And while that won’t be a good thing for the organizers of the lost events, it very well could restore a measure of sanity to an industry that for years has been clamoring for exactly that.

[Artnet News]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember what Mike Tyson said: everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.