Opinion

Why Some Protest Photographs Transcend the Moment They Capture and Make Social Movements Iconic

Certain images stemming from the unrest in the US are sure to be remembered in years to come.

Certain images stemming from the unrest in the US are sure to be remembered in years to come.

Kevin Moore

The best historic photographs don’t just document events but carry a residue of the mood. Some even become an emblem of a cause—they become iconic.

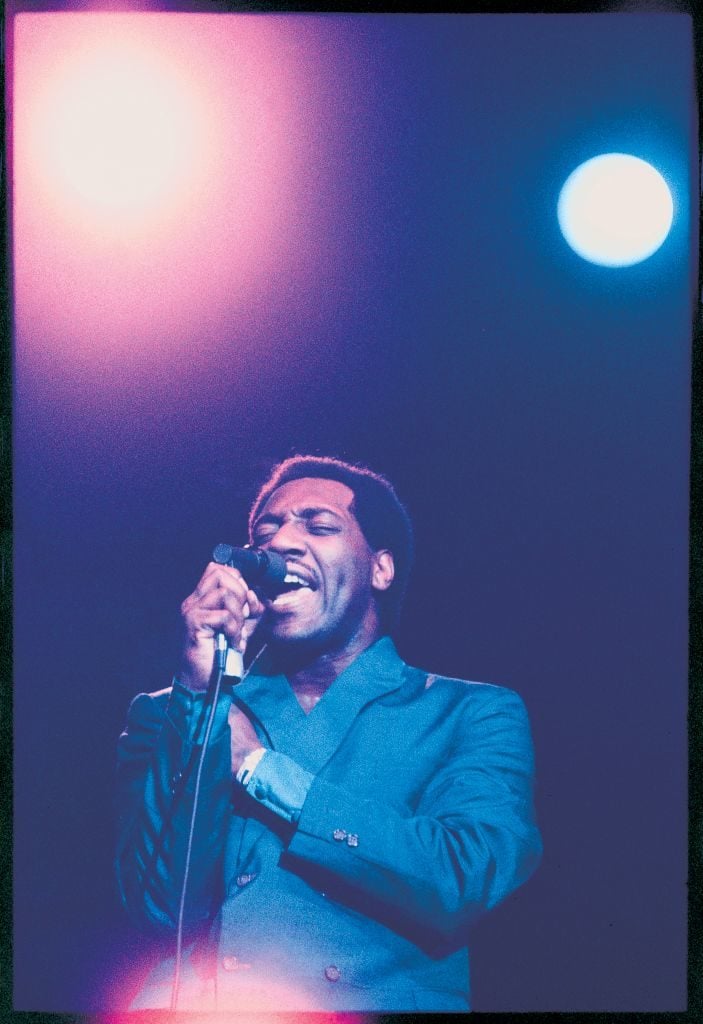

Elaine Mayes’s photographs of the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, for example, taken on assignment for the teen music magazine Hullabaloo, capture not only the intensity and style of the diverse performers—Janis Joplin wailing, a suave Otis Redding, Jimi Hendricks grimacing, a sacral Ravi Shankar—but also the peaced-out crowd, the flower children assembled for what would become the pinnacle of hippie culture’s highest moment: a tribal weekend of social transformation, real or imagined.

Monterey was the first of the music festivals, preceding Woodstock and Altamount, and it was the most positively generative (Monterey produced musicians, Woodstock produced agents, someone later said). Mayes now gently disparages her own body of work as “commercial,” but still says the experience of Monterey was blissfully transformative—“a vision for a way of life.”

Singer Otis Redding performing at the Monterey Pop Festival at the Monterey Country Fairgrounds on June 17, 1967 in Monterey, California. (Photo by Elaine Mayes/Getty Images)

Some images transcend the circumstances out of which they were born, expressing an almost otherworldly, fantasy version of events that took place. Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936) encapsulated in familiar Madonna-and-child format the hardship endured by men and women during the Great Depression. Such images, usually created as reportage for mass circulation, quite literally have a job to do, in the sense that they are created to show what is going on in the world and—if they are very effective—can even incite real political action. Lewis Hine’s Sadie Pfeiffer, a Cotton Mill Spinner (1908) was created to expose child labor and contributed to various legislative reforms.

Now, at the tail end of this terrible spring of 2020, we find ourselves embroiled in layers of crises, starting with a pandemic that has killed more than 100,000 Americans; nationwide protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police; and a President and administration either at a loss to manage the chaos or skillfully taking advantage of it, depending on how one looks at it.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has not produced many iconic photographs, the recent protests against police brutality have delivered a variety of alarming and inspiring contenders as instant icons of the times.

A protester carries a U.S. flag upside-down, a sign of distress, next to a burning building early Friday, May 29, 2020, in Minneapolis. Protests over the death of George Floyd, a black man who died in police custody Monday, broke out in Minneapolis for a third straight night. pic.twitter.com/mH6Iy8fbDj

— Julio Cortez (@JulioCortez_AP) May 29, 2020

Images of crowds holding signs with slogans such as “We Can’t Breathe,” “Justice for Floyd,” and “No Justice No Peace,” have provided a density of visual material to help us better understand the scope and sentiment of the protests. More invitingly, other photographs have delivered condensed moments of heightened drama: Julio Cortez’s dramatic photograph of a protestor triumphantly hoisting an upside-down American flag in front of a burning storefront, taken on May 28 in Minneapolis, graphically conveys the turn to violence and its apparent justification in a malfunctioning nation.

On the more contemplative front, Paul Fischer’s photograph of the White House with its lights off, taken at night on June 1 as protests got hot outside the President’s home, presents a powerful symbol of abandoned leadership. As Fischer wrote in a Twitter post: “This is a resignation. It should be taken as resignation. If your country is in crisis, your cities are burning, your police forces are assaulting, murdering, and kidnapping people, and you turn the lights off and hide? You’re not the President. You’ve resigned your duties.”

For me, the most concise yet complex photograph to emerge is one by Mark Clennon of a shirtless Black man, seen from behind, shaking a fist at Trump Tower. The image, taken during a peaceful protest on May 30, has already circulated widely, both in the US and overseas. Black anger confronts the ultimate symbol of white power: the Trump brand in bold brass signage. The photograph also suggests the larger meaning of the moment: we are witnessing something more than Black lives taking a stand against police brutality; the whole of democratic citizenry is standing up against an increasingly authoritarian government, controlled by a few.

.@TIME https://t.co/xwNixiyfxH

— MARK CLENNON. (@thisismarkc) June 2, 2020

Which of these photos may help lead to real change? It is a difficult question to answer, and perhaps not the right one to ask. In some ways, events become inseparable from images, and what was once a widespread expectation of documentary photography—to show the world images of shocking poverty, brutality, or tragedy, and thus to spark action—has become a matter of disinterest. And this does not even take into account our gross desensitization to images of violence and suffering in an accelerating and image-clogged world. Overwhelmed and distracted by the quotidian humdrum, we turn away. As Susan Sontag wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), “Wherever people feel safe… they will be indifferent.” Thinking back to Monterey, hippie culture’s most obvious legacy was not political change but lifestyle consumerism and Whole Foods.

But even then, there is at least one remarkable exception: a Catskills summer camp for handicapped children that was formed in the early 1970s, which is the focus of the recent documentary film Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution, directed by Nicole Newnham and former camper Jim Lebrecht. At the camp, disabled youngsters—left largely to their own devices to smoke, have affairs, and do all the things ordinary adolescents and teenagers do—went through a transformative experience. Many, such as Judy Heumann, went on to fight for disability rights during the 1970s, staging sit-ins in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, DC.

The film’s remarkable period film footage (shot by members of the People’s Video Theater) shows disabled kids playing baseball, flirting, and gathering for afternoon chats, and serves as an archive of a quiet revolution. Perhaps this is the real lesson of lived experience and documentary imagery: sometimes actions inspire or warrant documentation, or are even sparked by it. But we must remember that potent experiences—especially those that change us and inspire us to create change for others—ultimately need no documentation at all.

Kevin Moore is the New York-based artistic director and curator of FotoFocus in Cincinnati.