Opinion

The Gray Market: How the Met and the Shed Are Sharing Their Wealth in Two Very Different Ways (and Other Insights)

Our columnist considers what it really means to "redistribute privilege" as a wealthy cultural center.

Our columnist considers what it really means to "redistribute privilege" as a wealthy cultural center.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, examining philanthropy at two of New York’s newest and oldest arts nonprofits…

On Friday, my colleague Ben Davis reviewed the Shed, Manhattan’s latest starchitect-designed, billionaire-approved arts institution. At a cost of $475 million, the Shed has been positioned as the potential saving grace of Hudson Yards, perhaps the most targeted thing to rise out of New York City since King Kong climbed a skyscraper.

Two main traits aim to separate the Shed from the institutional pack. The first is its building (designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Rockwell Group), which can be reconfigured inside and out to accommodate any event. The second is a programming calendar of A-list cross-disciplinary mashups, like a concert series on the history of African American music directed by Steve McQueen and Quincy Jones or a “‘kung fu musical’ with tunes by Sia.”

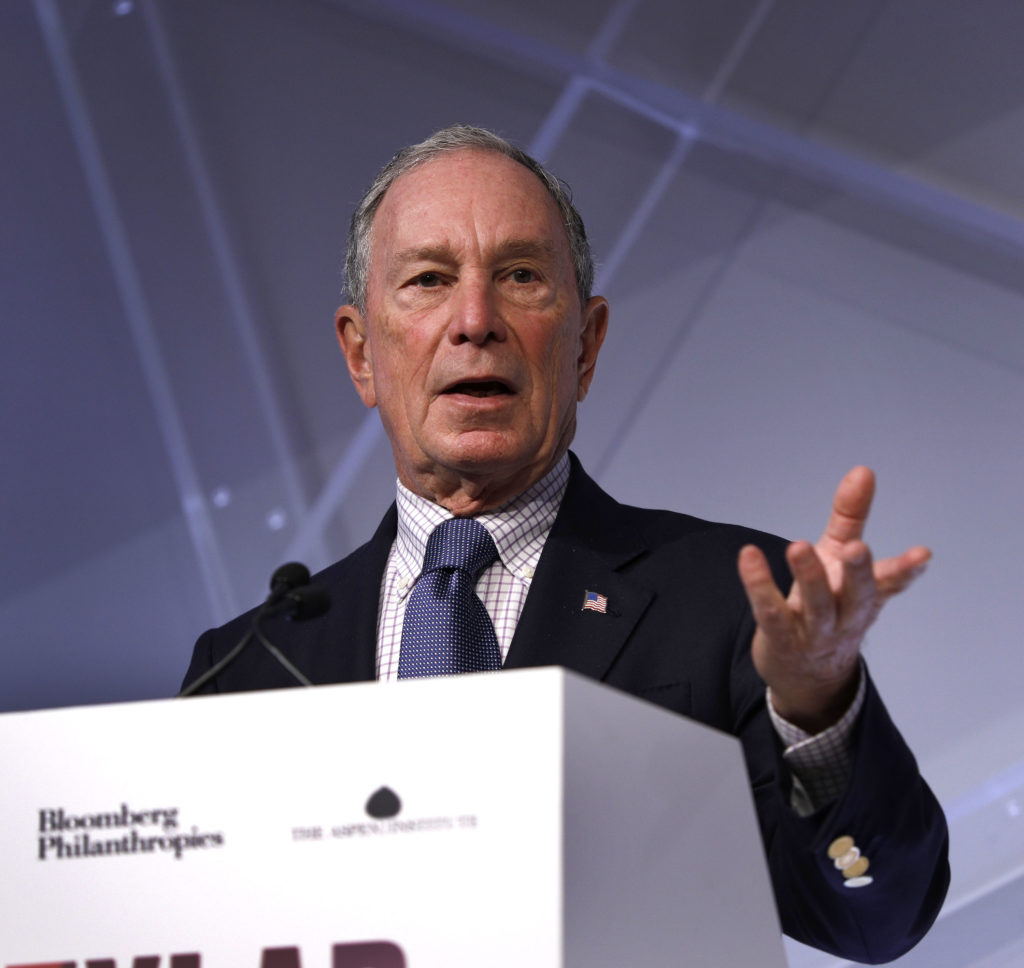

Based on Davis’s report from the opening festivities, though, the Shed is also infused tip to tail with rhetoric about inclusivity, social justice, and, in the words of CEO and creative director Alex Poots, the need to “redistribute privilege.” And there’s an awful lot of privilege to go around. Gifts from a shock force of plutocrats made the institution possible: $75 million from Michael Bloomberg, $45 million from property developer Frank McCourt, $27.5 million from travel and tourism magnates Jonathan and Lizzie Tisch, and many more.

Michael Bloomberg, billionaire and former Mayor of New York City, speaks at CityLab Detroit. (Photo by Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

This high-level collision of #woke words and gilded fortunes creates in the Shed a dilemma that Davis summed up this way:

[I]f you are a very rich person and are going to fund empowerment of diverse communities through an arts organization, I am not sure why you’d do it through a glittering brand-new one on the West Side, rather than through one of the thousands of local, culturally specific nonprofits dispersed across the city, which are starved for funding from both city and private donors in New York’s desperately asymmetrical, over-centralized landscape of mega-institutions and mega-donors.

He then answers his own question a few lines later: “You could give to those littler, long-standing organizations—but then you wouldn’t get to meet Steve McQueen or Björk or have your name on the cool Transformer building.”

Given the trajectory of Big Philanthropy in the arts this generation, I doubt Davis and I need to go around with spatulas to help many of you scrape your jaws off the floor. Big donors like big names and big new buildings. But that trend makes it all the more important to unpack what a much older and even more illustrious New York institution recently did to redistribute some of its own privilege—ironically, thanks to one of the most unpopular policy shifts in recent memory.

Visitors walk through the self-portrait section of the Edward Munch exhibition titled ‘Between The Clock and The Bed’ at the Met Breuer, November 13, 2017 in New York City. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

About three weeks ago, New York City announced that it would distribute around $2.8 million that the Metropolitan Museum of Art received (or estimates it will receive) during the 2018 and 2019 fiscal years to more than 175 smaller cultural organizations around the city. The total constitutes 30 percent of the projected increase in ticket revenue from the $25 mandatory admission fee for out-of-state visitors implemented last spring.

Per the New York Times, the Department of Cultural Affairs stated that half of the $2.8 million would go to “over 160 cultural development fund recipients that are in or serving what the city has identified as “high-need neighborhoods,” such as Harlem Stage and Staten Island’s St. George Theater. The remainder will go to 16 larger “institutions in city-owned property” within what have been designated as “underserved communities.” These include El Museo del Barrio, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Bronx Museum of the Arts.

There’s a really interesting reversal happening here. Metaphorically speaking, most of the art world pelted the Met with rotten fruit when it announced its new ticketing policy last January. (I thought critics were mostly missing the point.) Nowhere do I recall seeing any mention of this revenue-sharing policy at the time, which is especially odd since it should have at least mitigated the public onslaught on the museum.

But regardless of whether it was buried in the weeds or emerged later in hammering out a final deal with the city, the Met’s move stands in sharp contrast to how the Shed has so far chosen to redistribute privilege. Here’s Davis’s recap on the latter:

There will be commissions and workspace for local artists, including a show of more than 50 selected from an open call. The Shed has reserved 10 percent of tickets for low-income New Yorkers (though just whether Hudson Yards’s luxury mall complex truly wants to embrace lots of low-income New Yorkers passing through is not clear).

Along with the more star-studded stuff, in May, the schedule features the likes of “POWERPLAY,” a “women-centered celebration of radical art and healing” targeted at 16- to 18-year-olds and featuring participants in the new institution’s “DIS OBEY” program of social-justice workshops with New York City students. The Shed’s schools outreach, McCall says, serves some 600 low-income kids in 20 schools and the New York City Housing Authority, with teaching artists helping them, through creativity, to voice the “issues they have within school, or at home.”

This slate of initiatives is not nothing. At the same time, it raises one of the central issues complicating charitable giving in the New Gilded Age.

Performers demonstrate a scene from the “kung fu musical” Dragon Spring Phoenix Rise during the the press preview for The Shed. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Like Davis, I think the Shed’s redistributive programs are sincere and can do some real good. Yet they’re also auxiliary to the institution’s main function, which is basically to present cool, high-level arts events with a diversity component to a paying audience. Donors to the Shed, including ticket buyers, are still technically enriching the cultural fabric of the city’s underserved. They’re just not primarily doing that. Mostly, they seem to be sustaining what looks like Live Nation for the Young (or Wannabe-Young) Collectors set.

It’s not entirely fair, but I can’t help thinking about the Shed in relation to the Red Cross: a major organization that makes a donor feel great and look great until you examine how much tangible good is actually being done by the donation. For the uninitiated, NPR, ProPublica, and others have been investigating the Red Cross for years, and their findings have been consistently disturbing. For instance, in 2017, NPR reported that “instead of 91 percent of people’s money going to services,” as the Red Cross used to advertise, “the real number could be in the 70s, or lower,” since as much as 26 percent of each fundraising dollar went to expenses. (Far more appalling examples exist, but the Shed doesn’t deserve to be associated with any of those.)

I don’t know how much of the average ticket fee to a Shed production is distributed among the programs that redistribute privilege in a tangible way. I’m not even sure if the institution can calculate that at such an early stage in its life cycle. (An email sent over the weekend didn’t turn up a response before publication time.) But unless you’re specifically earmarking a donation for Open Call, DIS OBEY, or ticket subsidies for low-income residents, I suspect the answer is “not much.” And regardless of how each dollar is subdivided, all those fractions are staying inside the Shed, which will decide for itself how best to advance social justice in the arts.

That’s not the case with the Met’s revenue-sharing policy. People who think they’re giving solely to this massive, illustrious arts institution by buying a ticket are actually giving some of their money directly to dozens of other, smaller cultural organizations boosting their communities at a more grassroots level. It’s a kind of reverse Trojan Horse, sneaking privilege (see: cash) outside the walls directly to the people who don’t have access to it, so they can be the ones to decide how to use it themselves. In the process, it evolves an admissions policy initially torched as elitist into something with a surprisingly socialist endgame.

Obviously, there are distinct limits to the good being done here. The Met is only redistributing a portion of the general admission fees for out-of-state visitors, not going Robin Hood on each and every one of its revenue sources. And the city, which received the cash in the first place, appears to be the one who makes the final call about how these funds are redistributed.

Still, the museum and the Department of Cultural Affairs should be applauded for positioning the Met as a big fish with a responsibility to the larger arts ecosystem. Despite the shape-shifting ability of the Shed’s architecture, it remains to be seen whether New York’s newest arts institution can transform into the same kind of team player as one of its oldest just did.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Acting your age isn’t always a virtue.