Art & Exhibitions

Jeff Koons Talks Creativity, the Market, and Cicciolina

He destroyed certain works during the custody trial due to their content.

Photo: Jeff Koons.

He destroyed certain works during the custody trial due to their content.

Amah-Rose Abrams

Jeff Koons

Photo: via Observer

Jeff Koons’s unique output of art divides audiences and critics alike, with his work attracting both general disdain, and pure adoration.

This split view runs parallel with the increased prices his work can fetch at auction and his ever-increasing influence. His retrospective that closed out the Whitney in 2014 remained open for 36-hours straight on its final weekend to accommodate demand.

But you can hardly speak of Koons without opening up a larger discussion on taste.

Koons recalls walking around his exhibition at Versailles in 2008 to eavesdrop on the crowd (it seems many artists like to do this, including Tracey Emin). He heard a security guard walking around the installation saying, Merde, merde, merde,” in French.

“He was stirring up the crowd, because he was so upset,” the artist remembers, speaking to the Guardian. The guard has been replaced, Koons added before opening up on other, more intimate topics.

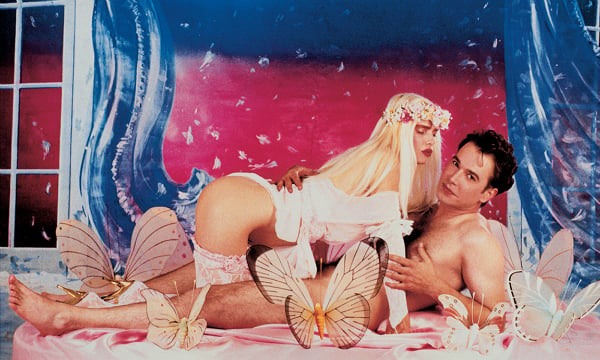

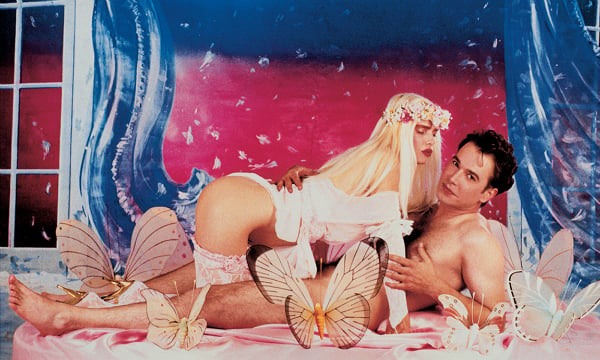

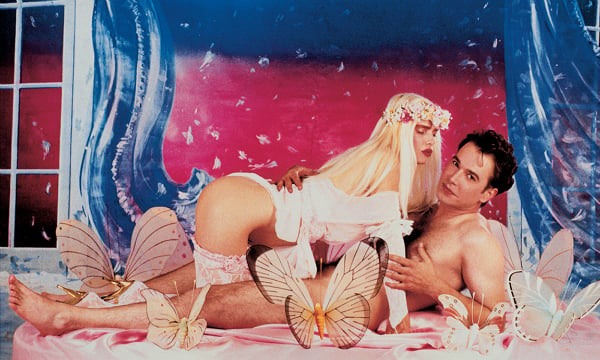

Jeff Koons, Ilona on Top (Rosa Background) (1990).

Photo: via the Guardian

In the same interview, Koons talks about his series Made In Heaven (1990), which shows him and his then wife, the adult film star Ilona Staller, known as Cicciolina, in different sexual positions in Pierre et Gilles style saturated color.

“When I made it, I was just thinking about the ideas around me,” he says. “I was involved with banal images. I realized that people respond to banal things; they don’t accept their own history; not participating in acceptance within their own being. I started then to take that into the body. Where do people start to feel guilt and shame and rejection of the self?”

Although Koons thinks of the roles played by himself and his ex-wife as universal.

“I think of Boucher, domesticated, un-domesticated. I think of all the polarities of the baroque and the rococo…My ex-wife and I were standing in there as Everyman and Everywoman. I wanted to present this Jungian, Dionysian way of looking.”

He did, however, destroy some of the works in Made in Heaven during the custody case over their son Ludwig due to their content.

“My ex-wife was saying that some of the works were pornographic. And of course my interests were just to protect my son,” he explains. “[It] was the only time in my life in which everything that is right was made wrong, ” he says of losing the case. “[I felt] a sense of, a loss of confidence in humanity.”

A proud father to eight children—Ludwig, a daughter from another relationship, and six children with his second wife Justine—Koons has been known to refer to his offspring as “biological sculptures.”

His actual sculpture tends to have a synthetic appearance being high shine, steel, occasionally incredibly large and, when figurative, have a cartoon like, overblown quality to them.

He refers to his bright, shiny balloon dogs as “Trojan,” imagining people dancing around them in a ritualistic act of worship.

“It’s very mythic. There’s a sense of the interior to the piece, which is a bit like a Trojan piece,” he extolls. “It’s very now—it’s like a balloon from a birthday party, and because it’s inflated, you imagine the birthday party was recent, not 20 years ago… At the same time, there’s a mythic and ritualistic quality; you can imagine people going around Balloon Dog in a sort of dance. A tribalistic quality.”

Jeff Koons, Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994-2000).

Photo: via ABC.es

Koons refuses to discuss the prices his work can fetch at auction—a 12 foot version of Balloon Dog (1994) was sold for $58 million at Christie’s New York in 2013—saying his secondary art market has nothing to do with him, although he seems unconformable with both the price paid for and the subsequent use of his work.

“It happens to everybody—the work is held by someone who doesn’t even particularly enjoy the work, and just has it stored in some warehouse and will sit there for 20 years. Or someone doesn’t understand it physically, and their motivations are just to show that they have the power to purchase.”

Jeff Koons at Frieze London, 2013.

Photo via: Hypebeast.

Jeff Koons, Baroque Egg with Bow BlueTurquoise (1994).

Photo: via jeffkoons.com

“Jeff Koons: A Retrospective” is on view at the Guggenheim in Bilbao through September 14.