The Big Interview

The Story of artnet, Part 2: How Founder Hans Neuendorf Helped Invent the Art Fair in a More ‘Innocent’ Time

In the second part of an interview series, Andrew Goldstein spoke to Neuendorf about his unusually energetic early career.

In the second part of an interview series, Andrew Goldstein spoke to Neuendorf about his unusually energetic early career.

Andrew Goldstein

When artnet founder Hans Neuendorf was in his twenties, Germany’s art world was reeling from the country’s recent defeat in World War II, engulfed by a cloud of shame and guilt. But German industriousness was beginning to re-emerge, and, for a young art dealer like Neuendorf, who ran a gallery in his native Hamburg and soon expanded to Cologne, the world was fresh and full of possibility. Especially, it seems, when it came to importing the dynamic art being made in England and America—which were invigorated by their victory in the war—to sell to German collectors at home.

After getting a life-changing chance from Ileana Sonnabend to show Pop art in Hamburg, Neuendorf dove into the dynamic new currents sweeping the international art scene, becoming an important node for bringing the work into Germany. Along the way, he helped found the first-ever art fair (Art Cologne), spent time in Los Angeles with his friend David Hockney, and bought and sold a staggering number of artworks that today are considered to be modern masterpieces.

In the second installment of a multipart interview to celebrate artnet’s 30th anniversary, artnet News editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein spoke to Neuendorf about this heady chapter of his life, and why he thinks the art world will never be the same again.

You borrowed about a dozen artworks from the Paris gallerist Ileana Sonnabend to stage the first Pop art show in Germany—an assortment of works by Warhol, Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, and Lichtenstein that today would be worth at least $1 billion. And all you were able to sell were the prints?

That was the only thing Illeana would let me sell. She also made me show Allan D’Arcangelo—he was less successful than the others, so she said, “If you want to show the Pop artists, you have to show him.” That’s why one of my first shows was Allan D’Arcangelo. Anyway, I really liked these paintings, the highways with the signs on the side. Beautiful. But he was considered to be second-rate at the time.

How was Hamburg as a city to sell art?

Well, I didn’t know the difference at the time, but Hamburg was a very, very tough place. To separate people from their money there is almost impossible. They’re supposed to be open, friendly to strangers, and always interested in new things. The opposite is true. They were money-minded and petty, and they didn’t know what they were looking at. So I had picked a very bad town. Cologne was very, very different. But Cologne was Catholic—there’s a different way of looking at things, enjoying life. The people have a completely different mindset. So Cologne was much easier. Later on, I opened a branch in Cologne, so I had two galleries for a while.

So your business began to spread beyond Hamburg.

And it’s not like I stayed at the gallery all the time. I locked it up for half a year and let it sit there and went to New York and Los Angeles. I was also very much involved with English Pop art. I showed Allen Jones. I showed a lot of Eduardo Paolozzi. I showed Richard Hamilton, Colin Self, and David Hockney. David became a close friend.

Was there any insight you had that helped make your business successful? How did you make the gallery work?

I never thought about it. It was an adventure, it was never business, and I didn’t look at it as a way of making money. In fact, nowadays dealers are complaining that the big galleries are making all the money. We weren’t making any money, and we didn’t have any expectation of making money. We were happy to get by, to be able to pay the rent, to be close to the artists. The way we looked at art was very different then. Art developed in systematic paces, and there was a logical process for how you got from one movement to the next. So artists would occupy a certain territory, like they would experiment with moving things, and that led to Op Art, and then that led to Pop art and all that.

It was an evolution of art, with a target, a goal, and that was progress. We thought that art moved along what later, looking back, would be seen as historical lines. And we wanted to be involved in that. Making money was necessary, but not something that we wanted to do. Nobody was thinking about money at the time. When you went to the bars where the artists gathered, they weren’t discussing money—well, maybe a little bit on the side, but they were mostly talking about art, which way it would go, was there an opening here or there. People were thinking about the future and how it was all evolving, and they were fighting over it. That was the thing.

What was the art that you believed in championing—that you believed was the right path?

Well, I believed in Pop art. I thought it was so refreshing and so wonderful. I befriended [Claes] Oldenburg and did multiples with him. Actually, I did do prints and multiples, and that was an attempt to make money—because I thought a lot of people couldn’t afford the originals, but I could sell them the prints. So that was my first real business.

Did people eventually begin to buy the paintings as well?

Yeah, slowly, a lot of people did. I did quite well when I showed the English Pop artists, like Allan Jones and Richard Hamilton, even though Hamilton was really slow—his production was almost nothing—so it was very hard to get the paintings. He wouldn’t let them go. But I also showed other artists, like Dieter Roth. All the artists who are now famous, I showed them. In hindsight you would say, “Well, that was very smart, to have found all the right artists.” But, in fact, everybody was excited about the same artists—it wasn’t a special discovery. There were other dealers pursuing the same things, like Heiner Friedrich and Bruno Bischofberger and Rudolf Zwirner. All these dealers, they were on the same path. You couldn’t make a mistake, in a way.

Because you would be the one to show the artists in Hamburg and Cologne, like it was a stop on their tour from city to city.

Yes. And then we did the first art fair in Cologne.

The first edition of Art Cologne, in 1967. Photo courtesy of Hans Neuendorf.

Yes, Art Cologne, the first art fair ever, which you helped start in 1967 as the Kölner Kunstmarkt. What was the impetus behind the fair?

It was because we were all separated in various cities—in Stuttgart and Munich and Cologne—and we said we’d all come together once a year so that collectors could go to one place and see what is available in the art world.

One person who did a lot to get the fair off the ground was Rudolf Zwirner, the father of the dealer David Zwirner. How did you know him?

He was an old friend. I started working with him in California—we were traveling together at the time and we did exhibitions together. He was in Cologne, and Cologne was the city where most of the activity in contemporary art was happening because [Peter] Ludwig lived there. He was “the Chocolate King.” He bought all these Pop art paintings, mostly from Zwirner. He was voracious. He wanted everything, and he bought contemporary art, mostly American. The Museum Ludwig in Cologne is now full of his stuff.

So that’s why everybody went to Cologne and started a gallery there. There was one gallery in Cologne called Der Spiegel, which means “the mirror,” and it was run by Hein Stünke. He knew the secretary of culture in the city, and he told him, “Wouldn’t it be a good idea to invite all the galleries in Germany”—and there were about 20 galleries in Germany, total—“to Cologne and have an event here? It would be great for cultural life in the town.” And that guy made it possible. So in 1967 we started the first Cologne Art Fair. It was Stünke and Zwirner who figured it all out, and I was there and some others who worked closely with Zwirner, and then we invited others who were a little bit further away. Altogether it became around 22 galleries, all from Germany.

So that’s how it happened, and then two years later [Ernst] Beyeler thought this would be smart to do in Basel. At the time, Germans were bringing their black money to Basel to deposit it there, so he thought it would be a good idea to sell them some art, because art is liquid, and you can ship it. Nobody was paying any attention, because no one thought it was worth anything. So that’s how Beyeler’s business evolved, with that German black money.

Visitors at the first Art Cologne. Photo by Peter Fischer.

What do you mean by “black money”?

When you have a business, you can always do a little bit of business on the side and take cash. Then the cash will accumulate, and you say, “Well, what do I do with it?” You can’t even spend it properly—you can’t buy property, because you have to prove where the cash came from. So they haul it to Switzerland. It was tax evasion. And then to convert it into paintings was a perfect business idea. Beyeler thought so, at least. That was how Art Basel came about.

So, back in Cologne, you had Ludwig, the Chocolate King, who later went on to found the city’s remarkable Museum Ludwig. How did you cultivate relationships with important clients like him and other collectors?

I did exhibitions, and I sent out invitations to a few hundred people in Hamburg and elsewhere—whoever I knew—and they would call me or come to the gallery and look at the paintings, and sometimes they would buy something. We had no other means of publicity. It was completely unknown. It was really very innocent, and kind of idiotic. Again, it was more of a cultural event than a monetary event. I actually think that all the money that’s coming into the art world now is really distorting the whole thing, to a degree that is already very dangerous.

But you can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube.

Yes, that’s true. But usually these things take care of themselves eventually.

You say you didn’t have any publicity. How important were the art critics to your gallery?

The critics were very important. We took them seriously, and they were actually coming to every exhibition. They were writing about it. That was a very good means of publicity. You’re bringing up a topic I’m energized about. We don’t have any critics anymore, honestly. Or hardly any, at least, because it doesn’t count for anything. What’s important now is popularity, not quality. When something is popular, it sells, and when it sells, the prices go up. And then the press has a reason to report on it. That’s how the art world functions nowadays. That’s very different even from how it was when I started artnet. At the time, we were still innocent and idealistic, but this money thing has completely ruined everything.

Considering how much artnet helped accelerate the market, you could say it’s the rule of unintended consequences.

Yes. They call it collateral damage.

Let’s come back to that later. Returning to your story, tell me about your LA experience. How did you meet David Hockney?

David Hockney was showing with John Kasmin, the father of [art dealer] Paul Kasmin. He had the best gallery in London next to Robert Fraser, which was where the Rolling Stones would show up for openings and all of that. Kasmin had Frank Stella and all the great American artists, but he also had Hockney. Well, I wanted to buy a David Hockney painting—I really liked his work, and I had met him—so I went to Kasmin, who was really very cagey. He wanted to sell the paintings himself at retail, he didn’t want to give me a discount. So we had an unpleasant conversation about it, and he said, “I don’t have any paintings. I can’t sell you any.” So it didn’t happen.

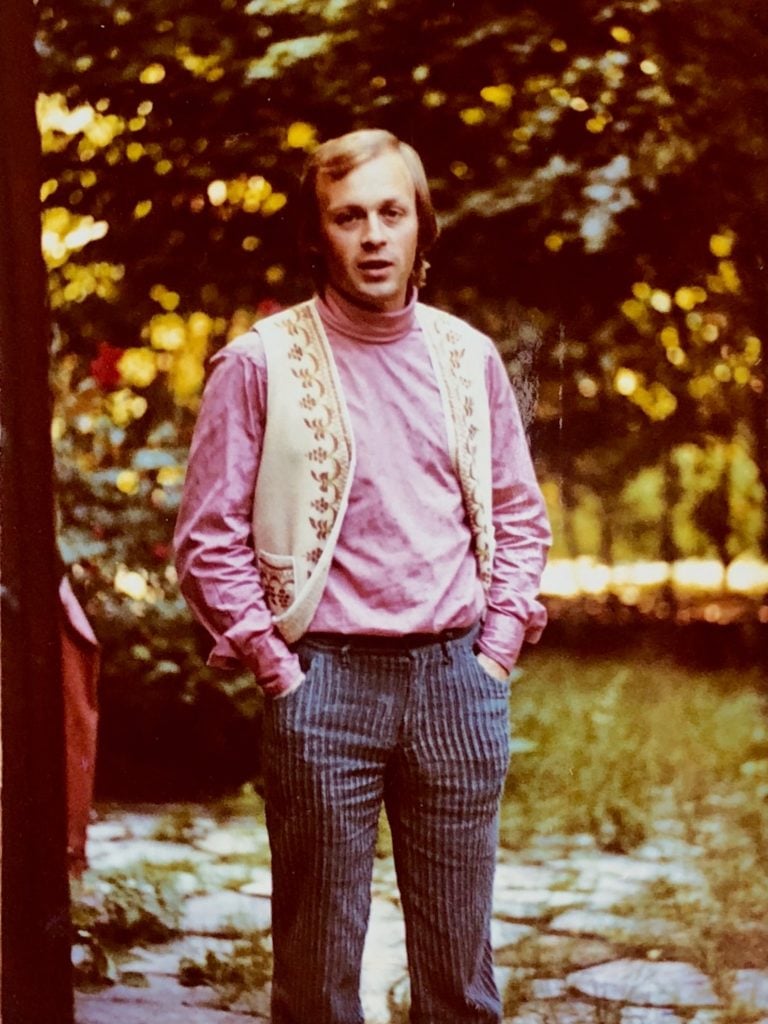

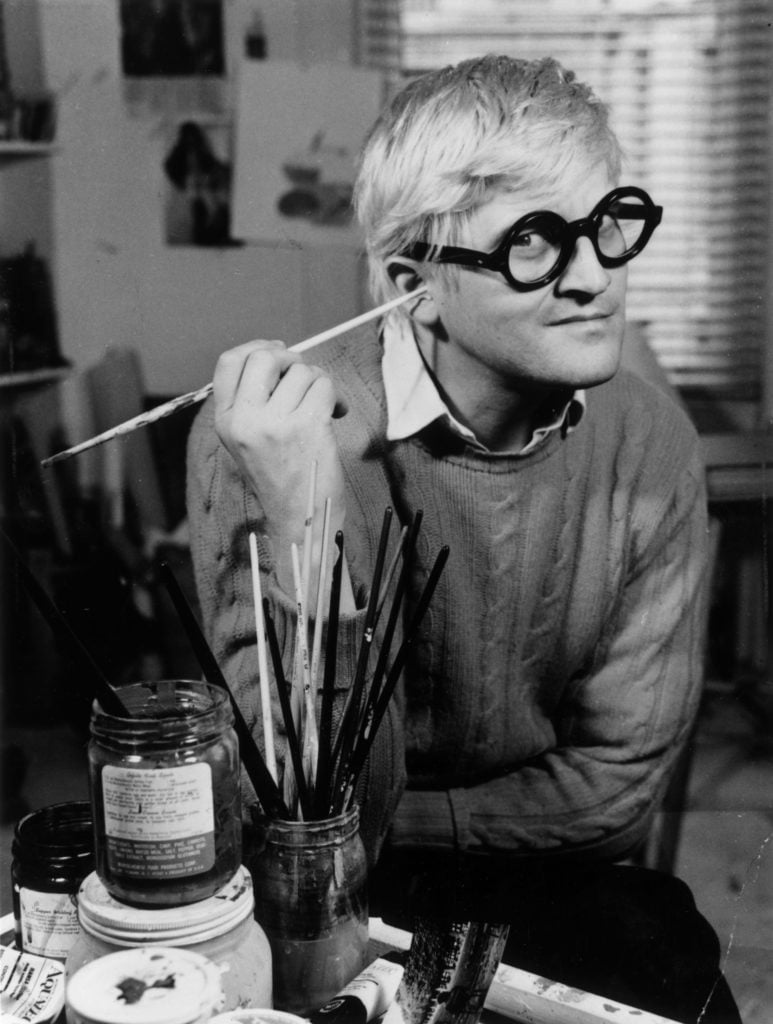

Then, when I came to L.A., David was already there, and enjoying himself. He had this blonde hair, you know, like “blondes have more fun.” But I needed to get my driver’s license, because I needed to rent a car—I wasn’t aware when I first went that you needed a car there, so I didn’t bring my driver’s license. And I needed a car of my own in order to pass the test, which I thought was kind of funny. So I asked David, and I passed my driving test in LA in David’s Ford Falcon. We got a ticket, actually, because I wanted to get some ice cream from an ice cream truck across the street, and a policeman gave us a ticket for $10. David was furious. He said, “You have to pay for this.” I said okay.

David Hockney in 1979. (Photo by Francis Goodman/Getty Images)

That’s very funny.

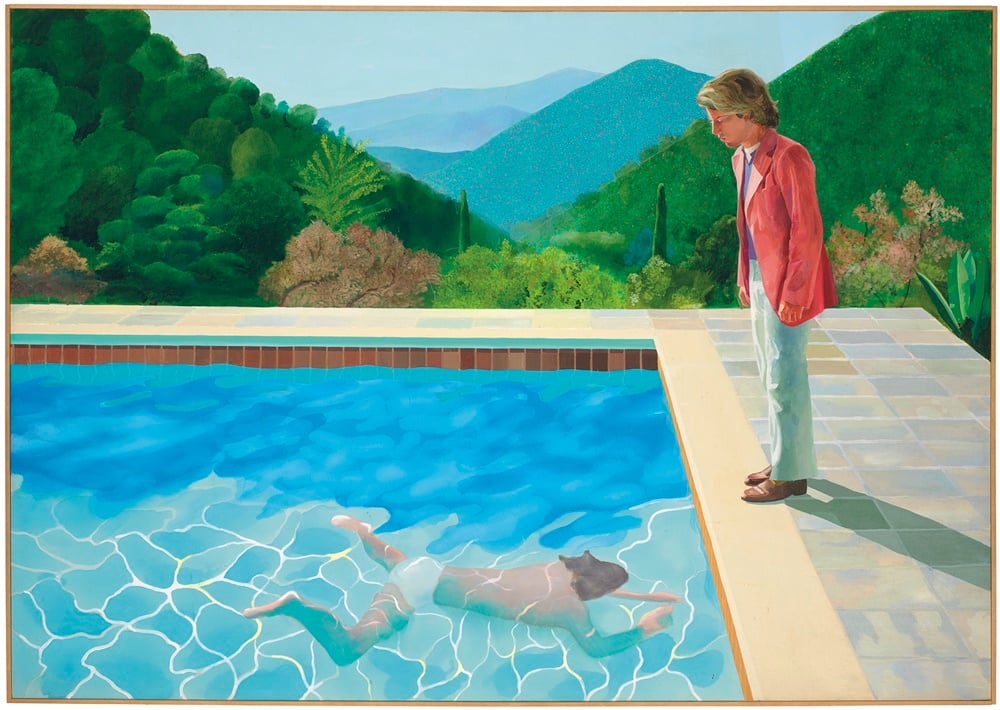

So, David painted in Los Angeles, and his paintings were shown at Landau-Alan Gallery, and I went there and saw five paintings. Big paintings. You know, two boys in a swimming pool, boys under the shower, then some of the buildings on Melrose, and the palm trees. Exactly what you want. They were priced at between $3,000 and $6,000, depending on size. I talked to the dealer and said, “Can you give me a discount?” And he didn’t want to give me a discount. I mean, David was in demand from day one. They knew they could eventually sell them at retail. I said, “Okay, I’ll pay you at retail,” and I bought all five of the paintings. Ever since, David thinks I’m a really smart guy.

Do you still have them?

No, I don’t—unfortunately I sold them to people in Hamburg and in other places. I’ve never heard of prices like what he’s selling for now. I never actually thought they could become very valuable. I just liked them.

His prices are extraordinary. Those paintings you bought could be worth $300 million today.

Yeah. There was a guy who was a professor of biology who did experiments with living rats, or something like that. I didn’t like that very much, but he was a very serious man, and he came to my gallery all the time. He wanted to buy a Hockney painting, and then he wanted to buy another Hockney painting. But he couldn’t pay for them. So I sold him one large Hockney painting for 12,000 D-Mark, and he paid it off in monthly installments for one year. Then he started on the other one, a swimming pool, which was also 12,000 D-Mark.

I don’t know how many million that is worth now. But what I liked about this guy, who is very sick now, unfortunately, is that he never sold them. He never sold any of the things that he bought. He was very deliberate in what he liked and what he didn’t like, and he lived with these things. He had built himself a little house outside Hamburg, which is filled with the furniture that he had used as a student. He has such a very modest way of living, and he’s got these paintings up on the wall. I’m sure everybody has been offering him millions for them, but he doesn’t sell them.

David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures), 1972, sold for $90.3 million at Christie’s in November 2018. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Amazing.

And then he started buying [Georg] Baselitz. He was the first one to buy Baselitz from me, and at the time you couldn’t give Baselitz away.

This was your show of the “Hero” paintings?

Yes, he bought two “Hero” paintings from me, and other Baselitz paintings, and then he started buying [Markus] Lüpertz, also. He’s got quite a good collection.

Going back to LA, how long did you stay there?

I stayed a month or so on my first trip when I bought these Hockney paintings, and I agreed to exhibitions with several of the artists the gallery was representing. One of them was Billy Al Bengston and another was Robert Graham. There were other artists who were there—Tom Holland, Ron Davis, and Larry Bell. They were all my friends, and we agreed on these exhibitions, and then I went back and started preparing a traveling exhibition of West Coast art to show in the German museums. There was a little catalogue, too. LA art was not very well known then, and still it’s not very well known. It never really caught on in Germany. It was just a world apart. Most of the stuff that I bought, I kept.

You know, a funny thing happened recently. I had just moved my art to a new storage facility and I found a crate that was eight feet long, and I opened it up and found two shimmering sheets of glass. I didn’t know what it was, and someone came to visit me to buy some paintings, and he saw these and said, “That’s Larry Bell.” I said, “Really, you think so?” And I looked in my inventory and found that, yes, there were two glass pieces that I thought had been lost. So I took them out and I sold them to the guy for $100,000 each. Later, I went to Larry and asked him, “So, what are these?” and he explained how to install them like two shelves on a wall and have a certain light shining down through them so that it would create a rainbow both above and below.

And he told me, “You know what, it’s really rare that you should have these.” They had been part of one of my West Coast traveling exhibitions, and they had never been installed because I didn’t know how to do it, and I forgot about them. Larry explained that when he made them, he had actually made several, and he had them all lined up on the wall when a small earthquake hit and they all fell down and shattered. So this is how my two became very valuable, because they were the only ones that didn’t break, because they were in Germany for the show. Funny, isn’t it?

Larry Bell’s Pacific Red (2016) on view at the Whitney Museum. Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

How big is your collection today?

I have a whole roomful of stuff, mostly artists who are not very well known anymore. Because during the time I was building artnet, I needed money all the time, so I sold everything that was valuable.

Well, it sounds like one thing you have learned over the years is that if you hold onto something long enough, it could be worth something one day. Maybe the rest of your collection just needs more time.

Who knows?

When you were building your gallery, how did you keep your inventory and your own art collection separate?

I didn’t. I didn’t keep artworks because I was speculating on their future market—I kept them because I couldn’t sell them. Now, some of them have been rediscovered, like Larry Bell. His market was pretty dead for a long time, 20 years or so, and it’s coming back in a big way. So it can happen, but I’ve seen other artists that have been forgotten completely. It’s not working the way it used to anymore. Like I said, it’s popularity that counts now, not quality.