Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, following up on my own thoughts…

BURN NOTICE

On Thursday, yours truly unpacked what we could learn about Frieze’s future from the paperwork filed by its majority owner, Hollywood-agency-turned-media-and-events conglomerate Endeavor, in its quest to go public the following morning. But a few days of research and analysis turned out to be relevant for about seven hours, as word got out by roughly 5:30 p.m. that Endeavor leadership—no doubt under the advisement of a murderer’s row of underwriters including Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Morgan Stanley—had decided to delay the IPO until an undetermined later date.

The postponement now puts Endeavor into a scenario all too familiar to auction urchins like me: one in which, despite the best marketing efforts of an illustrious and properly incentivized intermediary, an alleged high-value asset is publicly shamed by widespread disinterest among potential buyers, leaving its owners no choice but to retreat with a property newly confirmed as unwanted for anywhere near the advertised price.

Even most market novices know that any artwork suffering this fate at auction gets branded with the scarlet label “burned.” The idea is that the consignor might as well have chucked the piece into a roaring fireplace, since an unrecognizable slab of carbon would be just as salable as their freshly bought-in artwork.

Of course, the term “burned” is an exaggeration. Works that fail to find a buyer at auction often manage to sell later. But how much later? At what price? And through what avenue? These questions all burst into legitimacy the moment the chastened auctioneer murmurs “pass”—and the consignor generally wants to consider none of them until that ignominious moment arrives.

Although the answers to those questions aren’t universal, they do tend to be linked. An owner desperate for cash might be able to sell a burned artwork relatively quickly if they’re willing to stomach a steep discount from the reserve price in a private sale. But if they’re hell-bent on getting something close to the estimate range, they’re likely going to have to sit on the work long enough for some market-changing event to take place. And there’s no telling what the timeline for that scenario might be.

All of the above gives us a useful framework to think through what happens next with Endeavor. But it also clarifies an important way in which the financial market and auction market differ.

Bidding for David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) , 1972, which was offered with no reserve price at Christie’s post-war and contemporary evening sale in November 2018. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

CALLING IN THE FIREFIGHTERS

Thursday evening’s 11th-hour postponement was actually the second time Endeavor delayed its IPO this year. The first episode came in early August, when the company shelved the offering so that it would have a chance to release its second-quarter financials and complete a $700 million acquisition of On Location Experiences, LLC, a live-event production and “curated hospitality” specialist boasting relationships with the National Football League, the US Tennis Association, and a host of music stars.

That rationale sounds legit on the surface. But when Endeavor set the date for IPO 2.0 about two months later, the deal for On Location still wasn’t finalized, according to the Wall Street Journal. Its Q2 results apparently didn’t turn out to be much of an aphrodisiac to investors, either. Only a few hours before deciding to yank the IPO altogether, the company actually filed to drop the number of shares it would offer by 22 percent, as well as reduce the price range from between $30 and $32 per share to between $26 and $27.

The latter of these panic moves also has an analogue in the auction-house playbook. If the house’s specialists don’t find the level of bidder interest they expected for works without financial guarantees in the days leading up to a sale, it’s not uncommon for them to call their consignors and request permission to lower the reserve price (the unadvertised minimum price, usually calculated as a percentage of the low estimate, at which the auctioneer is permitted to sell the work).

No consignor enjoys taking this call, since it’s strong evidence that their return on the lot may be even lower than their most conservative expectations. Still, it gives them a chance to face up to the old business adage that 75 percent of something is better than 100 percent of nothing.

In especially dire cases, a house and a consignor can even agree to pull the artwork from the sale altogether. Like postponing an IPO, this move is both an embarrassment and a way to prevent an even more embarrassing outcome. Technically speaking, the work can’t be burned if you never actually expose it to the flames.

But here’s where artworks and IPOs part company—and why recognizing the divergence means more than just engaging in a thought exercise.

Employees pose with Tom Wesselmann’s Smoker #5 (mouth #19), at Sotheby’s in 2017. Courtesy of DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP/Getty Images.

SMOKE SIGNALS

Lots preemptively yanked from an auction are generally treated as if they are materially different from lots that get bought in. Part of the reason is that the former group gets entered into a kind of witness-protection program for artworks, where all records of their presence in the sale are scrubbed from auction-house websites and omitted from the results later sent to auction-price databases. Yet in both cases, the owner and the intermediary misjudged the market badly enough to find nothing but an empty well where they expected to find a revenue stream. From the standpoint of market demand, then, we’re talking about a distinction without a difference.

This is why I think we need a name for artworks that would have been “burned” if they hadn’t been secreted away in time for the public not to be able to see the conflagration. By virtue of their close proximity to the flames and the way they disappear in an obscuring haze, let’s call them “smoked” lots.

Savvy dealers, collectors, and analysts can still manage to sniff out the aroma of smoked lots when they reappear later. Gossip is forever, and it’s impossible to retroactively ghost the information in a printed catalogue (if one exists). But less dedicated observers may be none the wiser, giving the works’ owners and intermediaries an ethically squishy advantage if and when they try to return a smoked work to market.

For all their other problems, the financial markets are too well-monitored to allow this kind of nonsense. True, IPOs are substantially rarer and more visible in the trade media than the tens of thousands of non-guaranteed works consigned to auction every 12 months. (Fewer than 200 IPOs have been issued annually every year since 2015, according to analytics site Statista.) This difference grants smoked works a level of anonymity that aborted first-time stock offerings can never realistically enjoy.

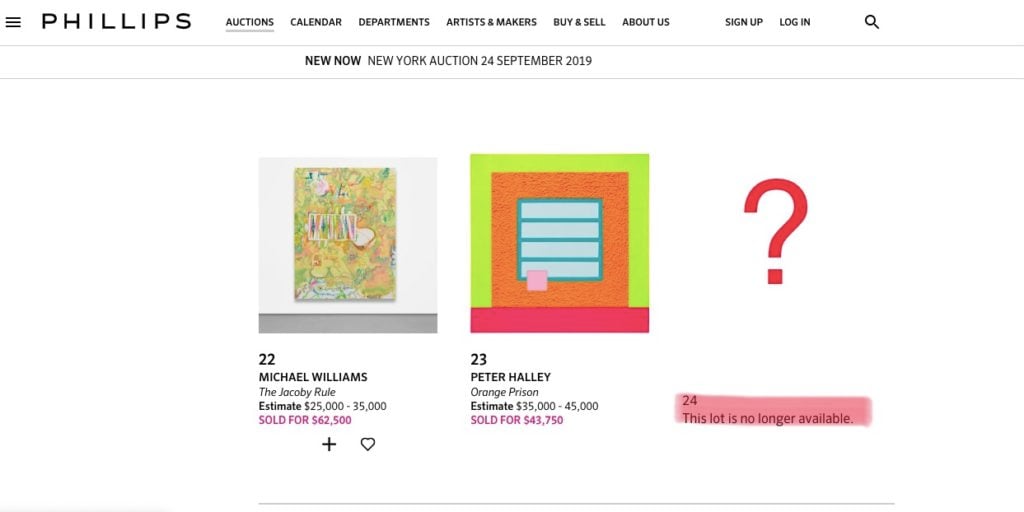

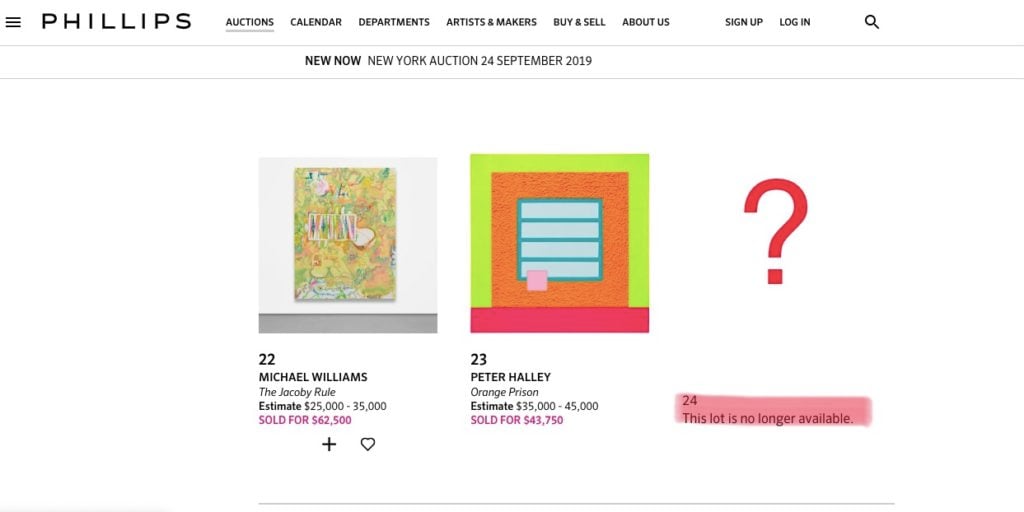

Annotated screenshot of the online results for the September 2019 “New Now” sale at Phillips New York, showing the empty space left by a possible “smoked” lot. Courtesy of Tim Schneider.

But even if this weren’t so, it’s not as if the US Securities and Exchange Commission would agree to de-list Endeavor’s S-1 filing (or its many amendments) once the company delayed its not-so-grand entrance to the New York Stock Exchange again on Thursday evening. That would qualify as blatant market manipulation. Endeavor’s competitors and other adversaries, as well as government and industry watchdogs, would sue immediately, and I suspect they would have a bulletproof case in any courtroom outside a Kafka short story.

Now, I’m not recommending the formation of a government agency to monitor auction sales. That said, I think Endeavor’s IPO yo-yo does clarify an important way in which the art market would do well to follow the financial market’s lead. Smoked artworks may be a short-term benefit to consignors and auction houses, but they do medium- and long-term damage to the trade by reinforcing perceptions of distressing inconsistency, if not outright unscrupulousness, in the eyes of outsiders wary of entering the market. (Attentive existing buyers tend not to be super into it, either… unless a work they consigned is the one being smoked.)

While some sacrifices would be required, self-regulation could eradicate this problem fairly easily—that is, if the major auction houses felt incentivized to enact it. Until that time comes, though, the auction market will have an inverse relationship to the IPO market in this respect: every delayed or canceled stock offering will make the financial markets more trustworthy, while every smoked artwork will make the art market less trustworthy. And when you’re losing to Wall Street in the realm of integrity, I’m comfortable saying that it’s time to re-evaluate.

[artnet News]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: even successful cover-ups come at a cost.