Analysis

How Scholars and Curators Helped Create an International Art Market for Pioneering American Modernist Marsden Hartley

The market for the artist's work, once confined to the US, has become much more widespread.

The market for the artist's work, once confined to the US, has become much more widespread.

Eileen Kinsella

Two stunning paintings by the American Modernist Marsden Hartley were the first things curator Mathias Ussing Seeberg encountered when he visited “America Is Hard to See,” the Whitney Museum of American Art’s inaugural permanent collection show at its new location in 2015.

Seeberg, a curator at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art outside Copenhagen, described the show as a “complete revelation” about American art. But it was Hartley’s vibrant colors and bold brushstrokes in the two 1914 paintings—Forms Abstracted and Painting, Number 5—that stayed with him.

“My first feeling, aside from that they were brilliant, was kind of embarrassment that I didn’t know this artist,” Seeberg told artnet News in a phone interview. “I felt this gap in my knowledge of American art needed filling.”

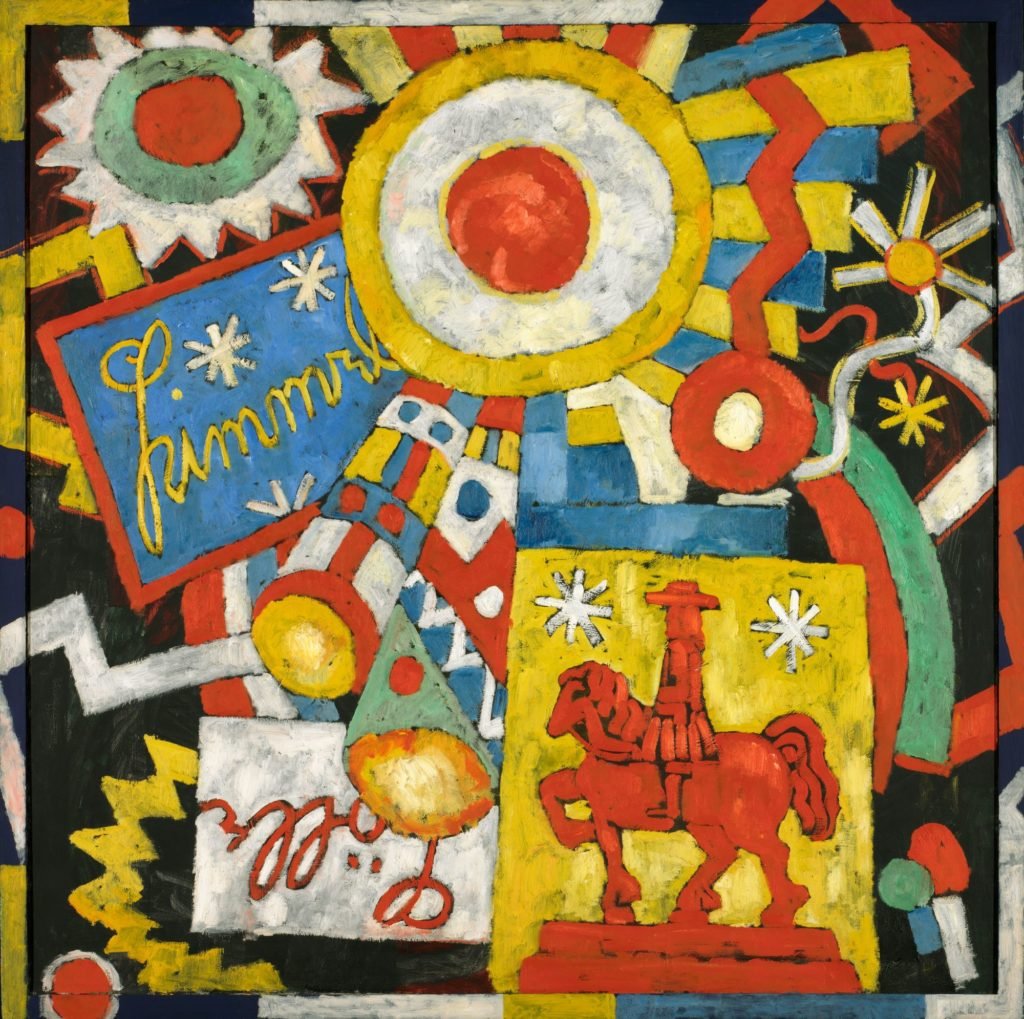

Marsden Hartley, Himmel (1914–15). Photo: Jamison Miller. Gift of the Friends of Art.

Image courtesy Nelson Atkins Museum of Art.

“I saw in Hartley’s work—especially in the later work—the seeds of what later became Abstract Expressionism,” Seeberg said. “It showed me there is definitely a lineage where you can look at Hartley and see Guston and Rothko and Pollock.”

That initial lightning bolt—further solidified after the curator saw more works by Hartley at the Brooklyn Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—was the impetus for “Marsden Hartley: The Earth Is All I Know of Wonder,” a major retrospective organized by Seeberg that just opened at the Louisiana Museum last week (September 19), and which runs through January 19, 2020.

In all, there are 140 works on view, roughly 113 of which are paintings. (The rest are mostly pastels.) It is the first major show of the artist’s work in Europe in nearly six decades, and it also illustrates his major influence on contemporary art.

Included in the show are videos and essays by artists such as Karin Mamma Andersson, David Hockney, Alex Katz, David Salle, Dana Schutz, Tal R., and Shara Hughes, each of whom draws something from Hartley.

Marsden Hartley, Abstraction (1912–13). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Hartley was born in Lewiston, Maine, in 1877, to parents who immigrated from England. After studying art in Cleveland in his teenage years, he moved to New York City in 1899 and attended painter William Merritt Chase’s art school before transferring to the National Academy of Design.

He met photographer and dealer Alfred Stieglitz in 1909, and following a solo show at Stieglitz’s New York gallery, traveled to Europe with the photographer’s support. While living in Berlin in 1913, he was associated with (and showed works alongside) Expressionist artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. When he returned to the United States in 1915, he began moving away from abstraction towards expressive landscapes, still lifes, and unconventional portraits.

“Hartley has always been at the forefront of collectors’ interests in American Modernism, particularly the Stieglitz Group, which included Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and Charles Demuth,” says New York dealer and American art specialist Hollis Taggart.

Hartley’s early introduction in Paris, through American writer Gertrude Stein, to Picasso, Matisse, and Cezanne, afforded him a certain cachet in America, which has endured until today, Taggart says.

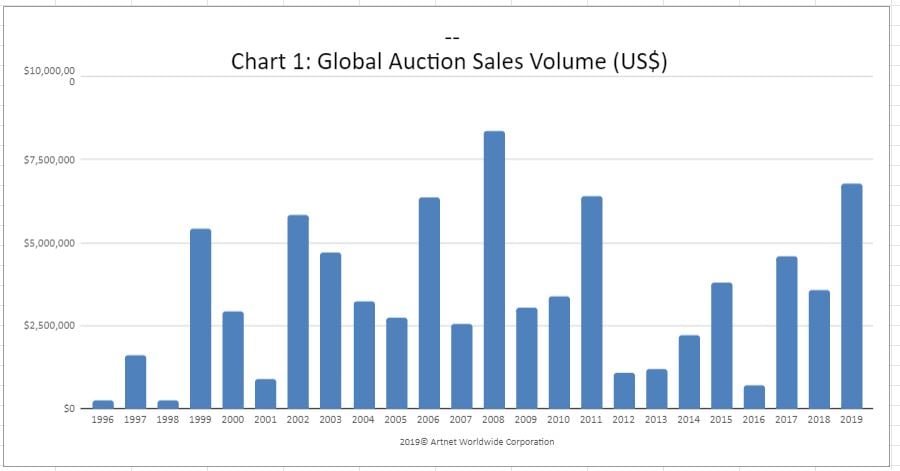

Global auction sales for Marsden Hartley from 1996–2019. Source: artnet Analytics

In the American art market, Hartley has never been ignored or entirely undervalued, and his star has especially been on the rise as of late. This past May, a decade-old auction record was broken at Christie’s New York when Abstraction, a work from 1912–13, sold for $6.7 million.

(The previous record, also set at Christie’s New York, came when a bidder paid $6.3 million for the 1915 painting Lighthouse in May 2008.)

Among the best-known Hartley works are his Berlin paintings. First shown in the US at the 1913 Armory Show, they continue to be prized by institutions and private collectors alike, with private sales bringing in even higher prices than the $6.7 million record.

These bold, decorative works “contain Hartley’s unique iconography and reflect the way he was influenced by the pageantry of the German army officers and parades,” Taggart says.

“These Berlin paintings are personal, which I think add to the mystique and interest,” continues Taggart, noting that Hartley encoded homo-erotic elements into the works. (While in Germany, Hartley fell in love with a German officer named Karl Freyberg, who was killed in the First World War.)

“A subtle homo-erotic undertone comes through in these works, and later, far more obviously, in Hartley’s Maine pictures in the 1930’s and 40’s,” Taggart says.

Marsden Hartley, Morgenrot (1932). Courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark.

But the market has broadened since historians have begun to focus on other periods of the artist’s work.

Eric Widing, deputy chairman at Christie’s and an American art specialist, joined the auction house at a time when American Modernism was first getting a closer look from scholars. At the time, O’Keeffe’s exuberant, blooming flowers tended to dominate the scene.

“Hartley didn’t catch on as early because he changed his style often,” Widing says, adding that his subject matter was not as immediately appealing to viewers.

Widing believes the turning point was a 2003 show at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, spearheaded by Elizabeth Kornhauser (now a curator at the Met), titled “Marsden Hartley: American Modernist.”

Marsden Hartley, Lobster Fishermen (1940–41). Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence Courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

Kornhauser “treated his whole career as worthwhile and basically revived the interest in the later work, which has a coarser, darker palette and is considered tougher by collectors and scholars alike,” Widing says. “She deserves a lot of credit for transforming people’s understanding of the work.”

Widing says Kornhauser was not immediately certain of her success; when she was preparing for the show, he says, she confided in him that she was concerned no one would come see it.

Both of them were surprised when a packed crowd filled out Christie’s Rockefeller Center headquarters for a lecture on the artist ahead of the exhibition. At the time, there was a dearth of information on the artist, according to Widing, and collectors traveled from cities such as Minneapolis and St. Louis for the event.

And since then, interest has only broadened.

“For years, the market for American Modernism was largely domestic,” Liz Sterling, chairman of Sotheby’s fine arts division, told artnet News. But there is a recent shift towards overseas appreciation of his work, she noted.

“I think we’re at a moment when there is great curiosity that goes beyond niche categories.”