Art Criticism

How the Many Dilemmas of Hannah Gadsby’s Anti-Picasso Show Feed Our Contemporary Cultural Doom Loop

"It's Hannah-matic, Part 2," from a 2-part series on "It's Pablo-matic" at the Brooklyn Museum.

"It's Hannah-matic, Part 2," from a 2-part series on "It's Pablo-matic" at the Brooklyn Museum.

Ben Davis

To read Part 1 of “It’s Hannah-matic,” click here.

Art museums, incidentally, do have a problem with over-romanticizing artists, and not just Pablo Picasso.

“This artist is a creative hero” is an easy entry point for modern audiences, particularly when you are dealing with experimental art that might require a lot of context to get into. In reviewing a show, I often find myself trying to undo some degree of distortion, as museums sculpt an artist’s biography to fit the presumed identifications of the art audience (I’m thinking, for example, of how the recent Alice Neel show treats her Communist politics).

Picasso died in 1973, just as museums were taking their turn towards blockbuster-ization. Certainly the success of Picasso’s media legend inspired the way modern art came to be marketed and presented to a mass public. Indeed, the Big-Name Artist Blockbuster era was the context for Rosalind Krauss’s essay from 1981, “In the Name of Picasso,” arguing that the obsession with the “Autobiographical Picasso” flattened our ability to see the artworks as artworks.

But that reference itself shows that there is a long critical history of viewing biographical readings of Picasso’s paintings as kitschy—which is, among other reasons, why many observers view Hannah Gadsby’s singular focus on Picasso’s biography as obtuse.

Personally, I am not so much of a formalist. Historical background does matter. It also matters if, in selling us an artist, a museum creates a distortion of the past. But saying that biography matters is different than saying that biography is all that matters. It seems to me that the Gadsby way of thinking simply flips the museum’s “good artist = good art” default marketing pitch on its head.

And this logic—simplifying the art, the life, and the relationship between the two to make a point—leaves us with all kinds of dilemmas in “It’s Pablo-matic.”

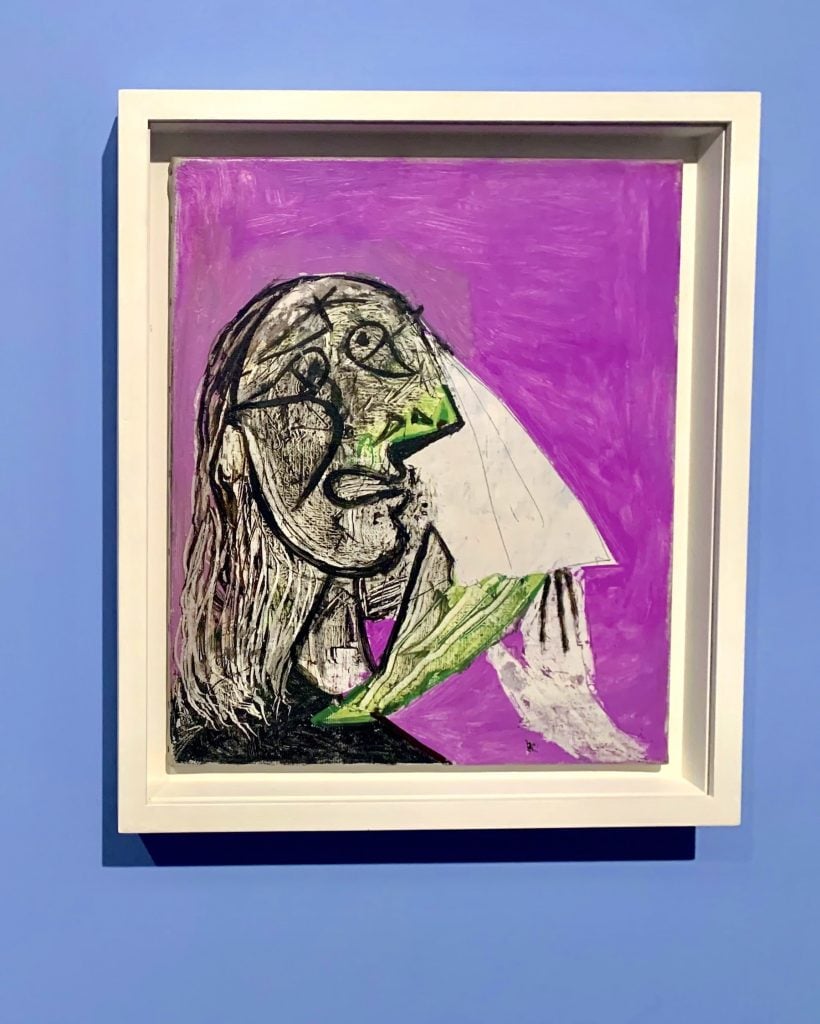

Pablo Picasso, The Crying Woman (1937) in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

Sometimes, Gadsby seems so consumed with proving that everything that Picasso ever did has to be absolutely condemned that they miss the chance to make their own point.

An image of Dora Maar as a “weeping woman” could have mentioned the violence in their relationship, particularly during the dark 1939 year in Royan during the Nazi occupation (I’d honestly like to know the facts: I’ve read about this period in both Arianna Huffington’s Picasso: Creator and Destroyer and in the fourth volume of John Richardson’s Picasso biography, and the specifics remain sketchy).

Instead, in the audio guide, Gadsby takes the opportunity to go after Guernica. “I have no time—no time—for all those declaring that Guernica was the greatest anti-war statement of the 20th century. Not least because it didn’t work,” they say, before going on to suggest, “If it’s a powerful, raw, and devastating anti-war statement you are after, I would recommend reading Anne Frank’s diary.”

From the evidence of the Nanette clips shown in the galleries, it would not be clear that Hannah Gadsby thought through their anti-Picasso argument in relation to any particular Picasso images. Gadsby quotes Picasso, and says his behavior toward women discredits “Cubism.”

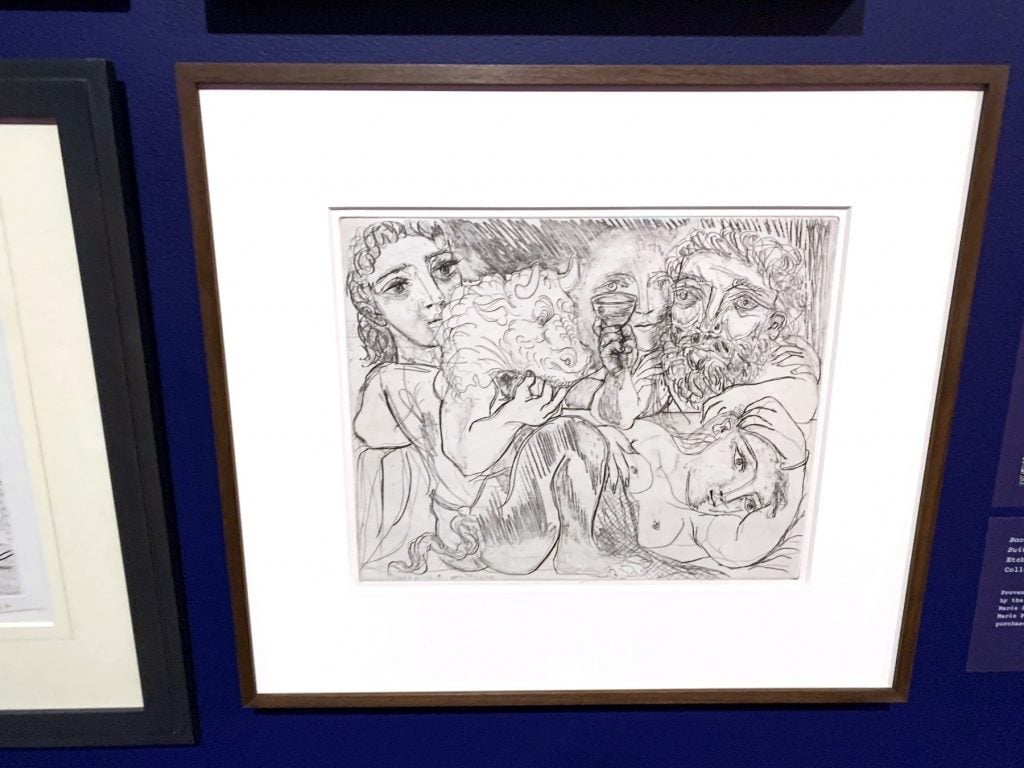

Etchings by Pablo Picasso in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

To make an exhibition, however, the Brooklyn Museum has to show actual artworks, so it needs a more concrete argument about stakes when it comes to viewing actual art. “It’s Pablo-matic” throws any and every anti-Picasso talking point into the mix, including some brief remarks on Picasso and cultural appropriation.

But mainly, the show homes in on how Picasso’s real-life relationships with women matter particularly for judging his art because he so often depicted women and sex.

The specific Picasso images brought in to serve the prosecution are mainly ones depicting nudes or sexual encounters, usually in classical or mythologizing settings, with the argument being that they encode Picasso’s demeaning ideology about women.

Pablo Picasso, Model and Sculptor Drinking with Minotaur (1933) in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

Hence, Gadsby’s one-sentence commentary on Picasso’s use of the imagery of sleeping female figures: “It is terrifying how benign this subject is considering how unsafe it would be to be an unconscious woman around someone like Picasso.” Or this, made about an etching showing a sculptor shaping a female figure, “No head. No arms. The sculptor shapes only what is necessary… for him.”

The theory that classical nudes in art have serviced the “male gaze” is not a new one. John Berger’s Ways of Seeing made it—on TV—more than a half-century ago. In fact, the position is so old that there is a long tradition of critics trying to nuance or complicate it (as Berger himself did).

Most importantly, feminist artists have had complex relationships—sometimes critical, sometimes ambivalent, sometimes recuperative—with images of female sexuality produced for the “male gaze.” One of the more provocative curatorial aspects of “It’s Pablo-matic” is how the curators lean in to showing graphically sexual work made by women, directly recalling these debates.

But it’s at exactly this point where the Brooklyn Museum’s too-deferential relationship to its celebrity guest curator really garbles its message.

The Picasso works shown here may not be all that memorable. But what visitors will likely remember from “It’s Pablo-matic” is Betty Tompkins’s big 1972 acrylic showing, in precisely painted black and white, a graphic close-up of (heterosexual) anal penetration, appropriated from a porn mag. “The world was not ready for Tompkins’s utter lack of self-consciousness or modesty,” the wall text notes, adding that French authorities deemed her “Fuck Paintings” obscene in the ‘70s.

Sure—but it seems important to note that other feminists criticized Tompkins as well, not just “the world.” After all, just one room over, the show features a beautiful canvas depicting two lounging nude figures by Joan Semmel. As Alison Gingeras has noted, “Semmel objected to Tompkins’s appropriation of these images on the grounds that they form an exploitative, misogynist industry, and could not be redeemed, even through their cooption by a woman artist.”

A gallery of “It’s Pablo-matic” with Betty Tompkins, Fuck Painting #6 (1973) at center. Photo by Ben Davis.

To this show’s credit, allusions to the internal battles among feminist artists in the ’70s and ’80s over how they approached the “male gaze” are sprinkled elsewhere and throughout, with some sense that these bitter fights damaged careers and undermined what should have been solidarities.

A text accompanying Marilyn Minter’s Big Girls (1986) highlights how the artist “found herself at odds with heated opinions about pornography among feminist artists,” even though the fact has little to do with actual content of the featured painting. Minter had to close a show of porn-inspired paintings in 1992 early, demoralized by the fierce condemnation she received. (In an oral history with the Smithsonian, she recalls being reduced to tears by a friend, Deborah Kass—the artist behind the Brooklyn Museum’s beloved OY/YO sculpture—who chastised her: “I hate this work. You can’t show this. It’s an affront to feminism.”)

Carolee Schneemann, Infinity Kisses II (1990-98) in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

The show’s texts nod to these controversies so often that it feels meaningful, but they do not clearly spell out why they are relevant in a show that takes Nanette as its jumping-off point. There’s a large, all-caps quote by Minter, randomly placed over a case with an ancient Aphrodite statue (itself a semi-random inclusion), that reads: “No one’s fantasies are politically correct.”

But why the reference to the perils of political correctness? The quote just hangs there, a loose thought.

Unidentified Greco-Egyptian artist, Female face and neck (Ptolemaic Period-early Roman period) and Unidentified Greek artist, Torso of Aphrodite (1st century B.C.E.-1st Century C.E.) in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

It’s convenient today to recall the ‘80s and ‘90s “culture wars” as a period that was only about a berserk religious right. But it also saw a movement of anti-porn feminists led by the late Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon make common cause with the pulpit-pounding religious right to reanimate censorship laws. Their argument was that there could be no ambiguity in how such images were read: “pornography is the theory, and rape is the practice.” The moral absolutism of these debates split the feminist movement: “the censorial climate they have fostered has caused untold harm,” argued Cathy Crosson.

Artists like Minter and Tompkins—whom Gingeras has dubbed the “Black Sheep Feminist Artists”—had to wait years for the kind of acclaim they get now, basically until a new generation of feminist thinkers made space for their appropriations.

The reason this is relevant background in “It’s Pablo-manic” has to be that Hannah Gadsby does seem to argue that images of passive female nudes or mythic orgies can only be received as literal documents of the desire that produced them and as aids to the continued male domination of women now (Hilton Als noted, “Gadsby often sounds like warmed over Andrea Dworkin.”) I do think that the background of the images is important to be able to unpack critically. But history also shows that Gadsby’s posture—insisting relentlessly that any pleasure taken from certain “problematic” sexual images is evidence of complicity—can have a real cost.

Mickalene Thomas, Marie: Nude Black Woman Lying on a Couch (2012), Dinga McCannon, Revolutionary Sister (1971), and Marilyn Minter, Big Girls (1986) in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

A cautionary note about the hazards of Gadsby’s argument seems implied somewhere in the background here. But in a show that has Hannah Gadsby’s name over the entrance, not many viewers are going to stick around to decode the fine print.

I have spent a lot of time unpacking this odd, muddled show. Why? I know that for one part of the audience, I will be guilty of man-splaining feminism, and I do not enjoy that thought. Then another part of the audience would prefer that I take much more dismissive delight in tearing apart this show’s “feminist cringe,” as meme-maker Jerry Gogosian termed it.

I do not really relish taking apart this show. It makes me depressed about the moment we live in. Let me explain why.

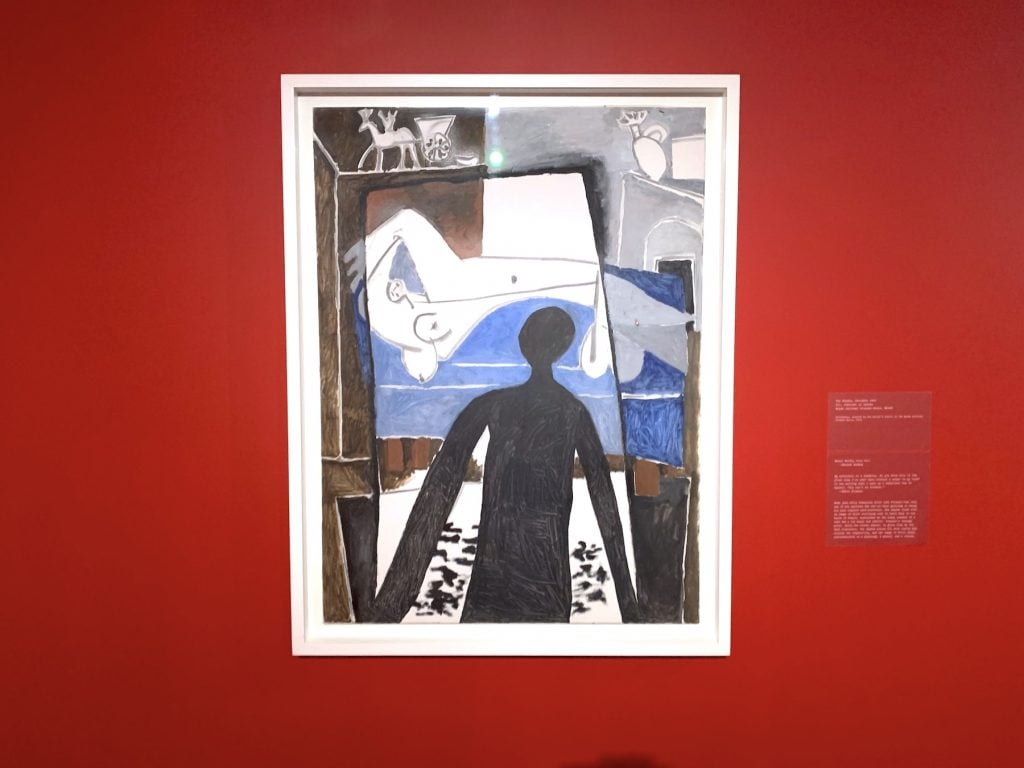

Pablo Picasso, The Shadow (1953) in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

Nanette, and the adulation around it, was clearly a product of the early Trump era, explicitly drawing a line from the celebration of Picasso to the celebration of Donald Trump. Terrified and disempowered at the electoral level, liberal commentators turned to culture—where they are, conveniently, overrepresented anyway—as the arena where some progress could be made.

Gadsby’s argument in Nanette, which plays looped in the galleries at the Brooklyn Museum, was clear on this mission:

You won’t hear too many extended sets about art history in a comedy show, so… you’re welcome… Comedy is more used to throwaway jokes about priests being pedophiles and Trump grabbing the pussy. I don’t have time for that shit. I don’t. Do you know who used to be an easy punch line? Monica Lewinsky. Maybe, if comedians had done their job properly, and made fun of the man who abused his power, then perhaps we might have had a middle-aged woman with an appropriate amount of experience in the White House, instead of, as we do, a man who openly admitted to sexually assaulting vulnerable young women because he could.

The argument contains a subreption, in that Hillary Clinton, the “middle-aged woman with an appropriate amount of experience,” happened also to be the wife of Bill Clinton, “the man who abused his power.” And Hillary Clinton’s inability to ever address this fact satisfactorily was something that Trump had exploited to excuse himself.

Nevertheless, the message was heard: Calling out abuse of power was more important than jokes.

Gadsby’s comedy-special-that-refused-to-be-a-comedy-special was perfect for its moment—the one where Kate McKinnon had responded to Trump’s election onstage at Saturday Night Live by dressing up as Hillary Clinton and tearfully performing Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. Late-night comedy became anti-Trump therapy. Even late night’s own writers would say (anonymously) that it felt as if “whatever I’m doing now, it doesn’t really feel like comedy” and called the situation, by early 2021, a “masturbatory rage ouroboros.”

Guess what happened next? Five years on from Nanette, most of the anti-Trump comedy shows have been canceled or have declined. People used to mock the very idea of mainstream conservative comedy. Now Gutfeld!, Fox News’s answer to the Daily Show, is the biggest thing in late night.

In art, the same kind of shift hasn’t totally happened, but there’s a definite percolating fatigue with “woke” culture. I’ve said for months that “It’s Pablo-matic” might be the moment when the mainstream art institutions had to grapple with just how uncool moralism had become.

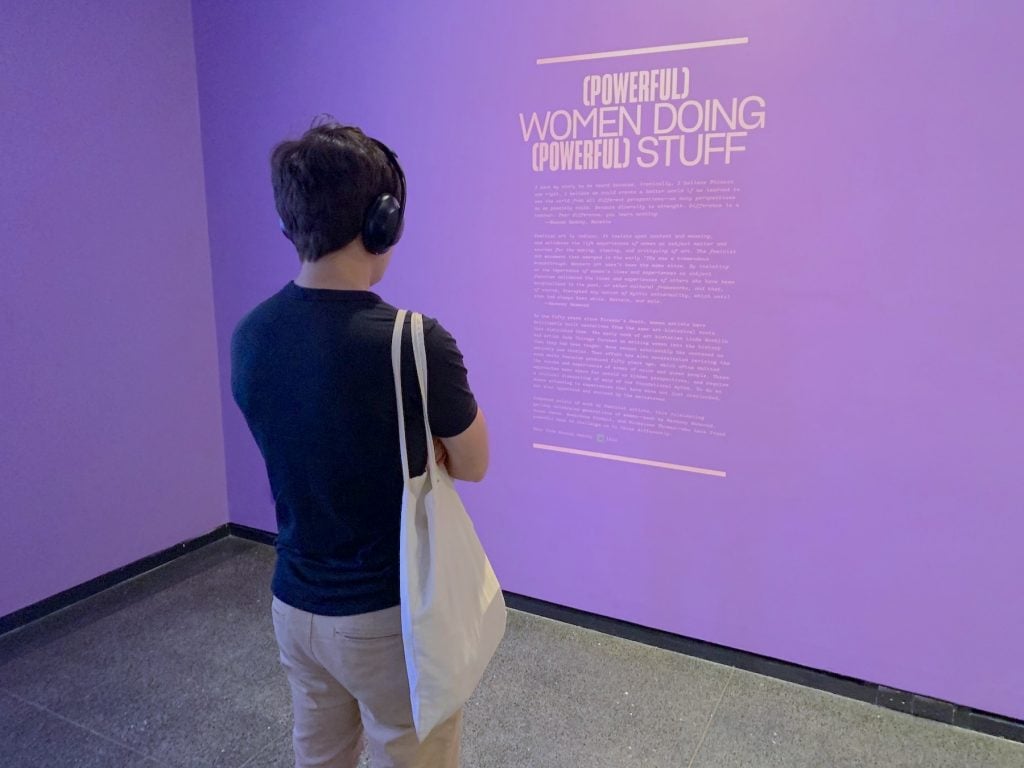

A visitor reads a wall text in “It’s Pablo-matic.” Photo by Ben Davis.

I argued, at the beginning and at the end of the Trump era, that putting too much stress on cultural consumption as the vehicle for salvation risked doing more harm than good. Among other things, by collapsing aesthetic judgement with moral evaluation it would train its audience to judge art by how worthy the person behind it was, thereby losing sight of whether an artwork was independently compelling. This would, in turn, inhibit people’s ability to see what worked, as art or as an argument, leading to isolation and fragmentation.

But one of the characteristics of the contemporary hyper-moral style is that criticism is often dismissed as backlash, or at least as conceding to backlash.

To be clear, our present moment definitely is one of conservative backlash. But it’s not only that.

The narrowness of Gadsby-ish arguments also, over time, clearly alienated a large set of culture consumers as well, on aesthetic grounds. Very early on in the Trump era, Molly Fischer, writing for New York magazine, noted the dominance of a style of “entertainment-as-think-piece,” tending towards either didactic outrage or simple moral lessons. She voiced a hunger for something more complex.

And plenty of lefties are alienated too, having been forced to defend anti-intellectual arguments, seeing politics reduced to virtue signaling, and watching progressive institutions paralyzed. The popularity of Olufemi Taiwo’s great book Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics is proof that there is a strong hunger for some kind of left critique of bad social justice discourse. (“I’m trying to move things away from what I see as an excessively moralistic direction towards a more practical and materially oriented direction,” Taiwo told Astra Taylor recently in Lux.)

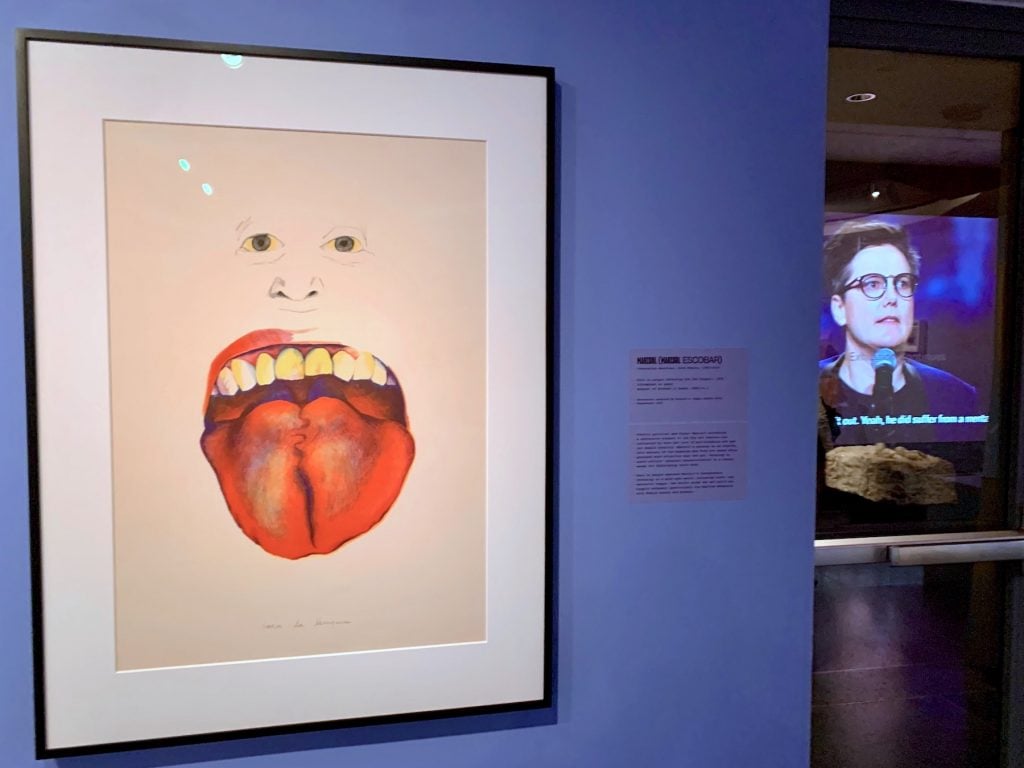

Marisol, Saca la Lengua (1973), with a clip from Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette playing in the background. Photo by Ben Davis.

But the hour is late. What’s scary is that we live in the middle of a gathering super-storm of political reaction. Women’s rights have been decisively eroded, and gender non-conforming people are at the center of a nasty campaign of bigoted scapegoating. And yet exhaustion, disaffection, and recrimination are gaining steam on the cultural level.

Gadsby’s co-curators at the Brooklyn Museum seem to know that there is some kind of alienation from a certain image of social-justice discourse. “One of the really important takeaways that we are stressing, and that we know is really important to Hannah, is that the idea of ‘cancellation’ is not remotely the point of this exhibition—nor is it mostly anyone’s goals in anything these days—as a simple, reductive kind of gesture,” Catherine Morris told Ben Luke before “It’s Pablo-matic” opened. Morris added that the show was about “giving complicated things the space to be complicated.”

But in the audio guide, Gadsby says plainly: “I don’t have much hope that the needle is going to move on ‘P.P.’—and by ‘P.P.’ I mean ‘Pablo Picasso.’ A cancellation of P.P. is an incredibly unlikely outcome.” They are saying that the patriarchy won’t let them cancel Picasso, while also very much arguing to the audience that we definitely should cancel Picasso. Morris may argue for complexity, but Gadsby’s arguments about what Picasso’s art means today are so totalizing and limiting that the majority of the feminist artists in the show disagree with them!

Clearly, the curators are aware that they need to nuance Gadsby’s argument (their own act of strategically softening the Big Name at the center of their exhibition). But the Brooklyn Museum wanted to do an exhibition with a Netflix celebrity, so the institution is not going to say anything too plainly about the flaws in Gadsby’s arguments, even though it seems aware of them. Gadsby, meanwhile, admits in the audio guide that they participated, even though they hate the show’s subject, because “I thought it would raise my profile.” It’s a crazy-quilt of faulty incentives, from end to end.

What alarms me about the spectacle of “It’s Pablo-matic” is the evidence that art institutions aren’t able to make better arguments, aren’t able to adjust, aren’t able to assess what has happened in the last five years or where they stand in the escalating doom loop of “woke” and “anti-woke” factionalization.

One final note: As recently as April—presumably as “It’s Pablo-matic” was coming together—the Brooklyn Museum’s staff has been forced to picket their own institution, demanding livable wages. “The museum likes to cloak themselves in social justice, but I think they really don’t like unions,” a union rep told my colleague Sarah Cascone, adding that the staffmembers “feel what they’re doing is really important, but they feel so disrespected.” Can we get a couple of Hannah Gadsby quips on this?