Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

So this is a bit of a long story but here it goes: I’m an art history grad student and while on a recent vacation in the Southwest, I took it upon myself to find James Turrell’s under construction magnum opus Roden Crater. With the help of Google Maps, it was much easier than expected. I drove my rental car as far as I could, and then walked the rest of the way. There were no barriers in place and there was no one there to notice my presence. Though still unfinished, it was magnificent. I took a ton of pictures and would love to have them accompany an article I’m writing about Turrell. Is this okay, or could I get sued? What about posting them on social media?

Wow. That must have been an incredible experience. You were able to see something that’s been in the works for 50 years. Since Turrell first acquired the site in 1977, the work has only been seen by a handful of art patrons, and Kanye West. Your photos represent a hot ticket, and a thorny legal dilemma.

For a project that has been so tightly guarded, I must admit I’m surprised that there weren’t any physical barriers to entry and no personnel. But this doesn’t mean that these photos of this unfinished work should be shared… I’m going to outline a variety of scenarios to try and dissuade you from posting these pictures.

Non-paparazzi journalists justify their occasional intrusion into the lives and private matters of others with the thinking that the information gleaned is important enough to the community at large, i.e. in the public interest. Do you remember when sitting President Donald Trump crashed that wedding party in 2017? The fellow who took the photos subsequently sued the outlets that used them. Esquire’s owner Hearst tried to defend itself using the journalistic protection for fair use, but the judge ultimately ruled against them. He wrote that Hearst would have had to add “new expression, meaning, or message to the original,” but the point of their story was just that the president had done this thing, a message that had already been accomplished by the photos themselves when they were posted on Instagram.

So if you were to publish your photos about Roden Crater in The New York Times, alongside an article that revealed Turrell’s project had disturbed an ancient Indigenous burial ground, this news would likely enable you to file the photos under journalism and avoid any backlash about copyright infringement. Especially since everyone would be angry at Turrell if he’d done that, though I am certain he did not, because it’s just something I made up.

If you’re considering a scholarly article in an academic publication or book, this would not be considered journalism at all and you’d definitely need to clear the copyright of the artwork with the artist. This is because you’d be using the photos as an illustration for your article—“See, here’s the artwork I’m talking about”—and that’s not transformative. Turrell is not an ARS artist, so you would need to reach out to his studio, explain the nature of the publication, and share the images in the hopes that he would approve of their publication.

To this, you might say, “But hey, can Turrell really hold the rights to something that isn’t even complete?” Unfortunately for you, copyright doesn’t need to be officially registered and is valid at the moment that a work is “fixed in a tangible medium of expression.” While, “fixed” may seem somewhat vague, Title 17 of the United States Copyright Code states that a work is fixed (and thus copyrighted) even when it “is prepared over a period of time, the portion of it that has been fixed at any particular time constitutes the work as of that time.” This means that any portion of Roden Crater that physically exists at any given moment is copyrighted by Turrell, and that holds true for any moment in which you took your photos.

Finally we come to social media. Remember how the Met and SFMoMA posted Glenn Ligon’s work on Instagram without his consent and then apologized for doing so? I discussed the situation back in June 2020 and explained that museums don’t tend to own the copyright for works in their collections. Even when they do, it’s always good to ask for permission. As an academic in training, I assume you’re respectful of Turrell’s place in art history, and probably don’t want to upset him for personal or professional reasons. I wouldn’t post these until the master is ready to reveal the project himself.

Stranger Things season 4 draws on 1980s horror movies, especially those based on the work of author Stephen King. Photo: Courtesy of Netflix.

I’m happy that Stranger Things has returned for its fourth season after three long years, but as a screenwriter, I have to ask about their originality. It’s clearly an homage to Stephen King and the movies made from his books, but at what point does homage become infringement?

For the past 50 years, art has tended to reference pop culture more and more, and we often get this kind of question from artists of many disciplines. Lest we forget that by the 1990s, Robert Longo and Cindy Sherman were doing such perfect recreations of Hollywood style that they each were enlisted by Hollywood to make their own Hollywood movies.

The lines distinguishing parody, pastiche, satire and homage from their source material can be very thin. Parody is, of course, a highly protected form of speech—dating back to a landmark Supreme Court decision that protected 2LiveCrew’s filthy and idiotic parody of Roy Orbison—based on the idea that parody comments on the original. When it comes to homage, all this becomes a bit tricker.

As discussed two months ago, the 2015 case that saw the Marvin Gaye estate sue Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams over “Blurred Lines” was mostly about homage. Thicke and Williams said, as their defense, that they strove to create the feeling of Marvin Gaye, without using any cords or arrangements from any one specific song. They still lost the case.

In researching this question, I’ve come to the conclusion that the main difference between parody and homage may be reverence, as parody mocks (sometimes out of love) while homage seeks to recreate the beloved elements of the original text. But it seems to be better in both cases if the original element is cited obviously. As this 2012 essay from the law journal SCRIPTed points out, homage is safest when you are “upfront” about the source from which you are borrowing. “For example, in Kill Bill Vol. 1, Tarantino portrays the highly identifiable character of a one-armed swordsman, which is based upon the earlier Asian film One-Armed Swordsman (Dubei dao, Cheh Chang, 1967, Hong Kong),” the essay’s authors state. It’s hard to argue that fans of kung fu films wouldn’t recognize the source of Uma Thurman’s yellow jumpsuit at the end of that film. Heck, the titutar Bill was even played by the star of Kung Fu!

So how do the Duffer Brothers get away with Stranger Things? Well for one, Stephen King likes it (or may have been compensated to say he does). And while I haven’t seen much of the show, it’s hard not to think of Stephen King when you combine small town horror, alternate dimensions, groups of young friends, telekinesis and a banging 1980s soundtrack. Like Kill Bill, the series wears its influences on its sleeve. Perhaps “Blurred Lines” would have been safe if they’d had a holographic Marvin Gaye dancing in the video, instead of Emily Ratajkowski.

Curiously, those Stranger Things creators are currently being sued, but not by the celebrated author. A screenwriter says they stole his idea for a similar story that doesn’t take its inspiration from King. I’m not a lawyer, but my money’s on the Duffer Brothers here. The show is defined not by its plot but by the rigor of that homage to King. That, and by its product placement.

Sure you can make an NFT of the Mona Lisa. But should you? Photo via OpenSea.

I have a query related to NFT copyright. Can we sell open source content as NFT?

Probably! There’s very little case law when it comes to NFTs, because the technology is so new. But I’m hedging my initial answer more than usual because I’m not familiar with the term “open source content.” I’m familiar with the term open source as it applies to software, but I have a hard time picturing what that means when it comes to creative or editorial content. Are you talking about memes? Darling, we’re drowning in NFTs made from memes.

Since the concept of open source content flies in the face of copyright, which only applies to “fixed,” ie finished works, let’s assume you’re talking about the public domain. Works can pass out of copyright eligibility, at which point anyone is free to do whatever they want with them. All that chintzy Mona Lisa merch outside the Louvre? It stinks because it’s unlicensed. There’s no copyright protection for that painting, because it was completed in 1517.

We address public domain more in depth for the question below concerning Winnie the Pooh, but for now all you really need to know is that if the work is from before 1900, you’re probably free to do whatever you like with it. So get nutty. Make an NFT where Botticelli’s Venus goes skateboarding with Bertha Mason to the tune of Eine kleine Nachtmusik, or whatever, and you can rest assured that no copyright infringement lawsuit will ever darken your door.

And, to me, that feels a lot more honest than a lot of the NFTs I see out there. Here’s Rick from Rick and Morty as Spider-Man, a steal at just $10,000. But do you really want to spend that much on something that may end up violating the IP of two different, major corporations? It may be that these companies come to view NFTs as a form of folk art and not worth the trouble of a lawsuit, but when you consider the language surrounding NFTs and how they’re all about the ownership of intellectual property, it feels disingenuous to sell something to someone that they may, in fact, have no right to own.

The meme ones are even worse, because you have to assume that some of the buyers believe that they’re buying the original meme, with all the rights entailed, when in fact, like gifs, memes are offered for free and have no real ownership or rights associated with them. These folks are only buying JPEGs.

If you’re looking for free content from which you can make an NFT, I would advise that you avoid memes and stick with masterworks from the public domain. It’s cleaner for everyone involved.

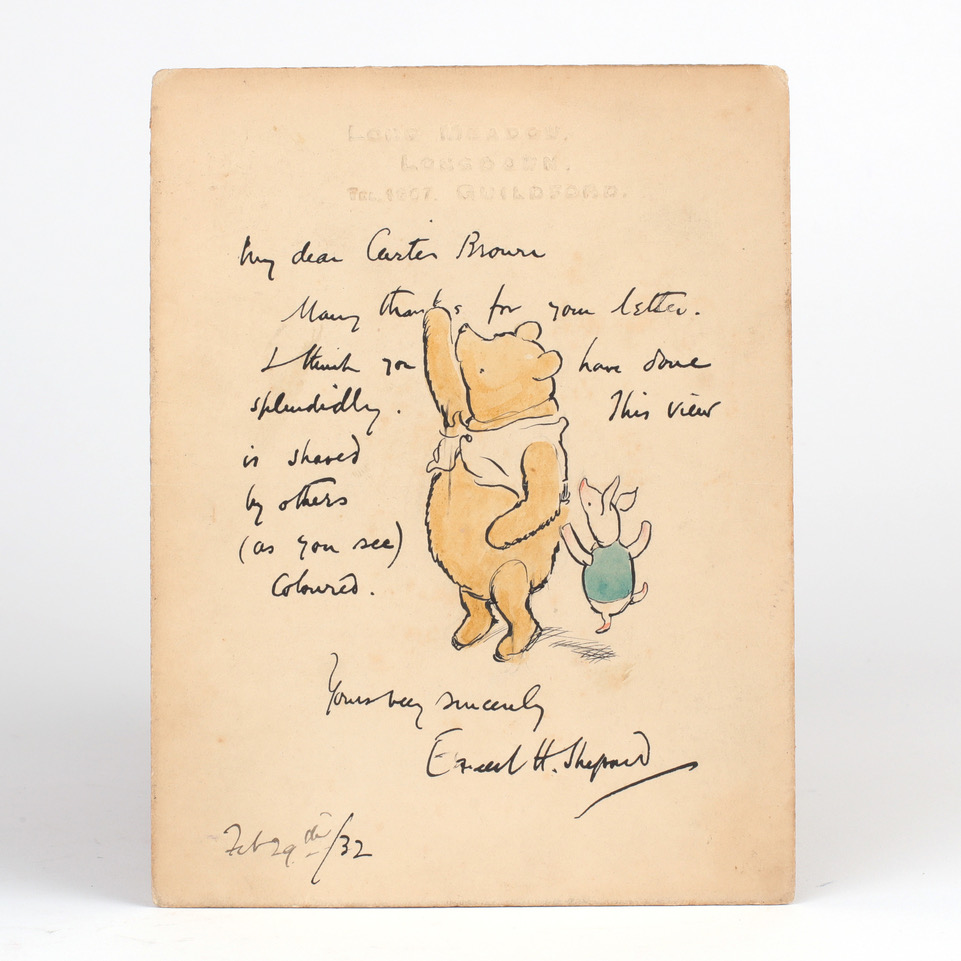

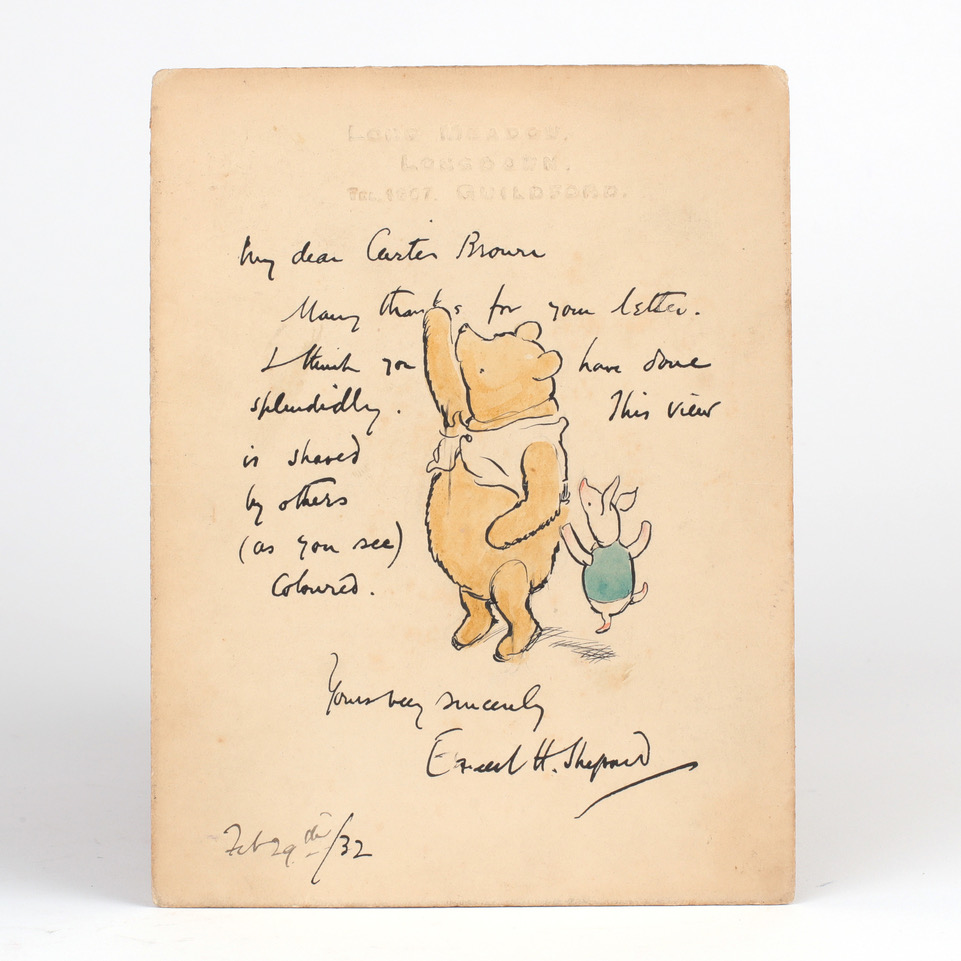

E.H. Shepard’s original drawing of Winnie the Pooh, from 1936. Photo: courtesy of Jonkers Rare Books.

I was recently sent a trailer to a movie called Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey? That involves Pooh and Piglet going on a killing spree? Why? Why does this exist?

Blame copyright expiration! As discussed in our NFT question this month, copyright in the U.S. only lasts 95 years after a works creation, or 70 years after the death of an author for works created after 1978. Pooh’s English creator A.A. Milne died in 1956, with Pooh making his first appearance (as “Edward Bear”) in 1924, so Pooh is now public domain. You may now feel free to do whatever you like with the character—from merchandising to snuff films and NFTs—with a few important caveats.

If you try to watch that trailer at the moment of writing, there actually isn’t any appearance of those beloved characters, just some generic footage of a bathtub with bloody handprints. I have a theory as to why, and it happens to explain some of the nuances of public domain. The costume for the movie, though impressive and terrifying, seems to have been based on the yellow fur, red shirt version of Pooh from the popular imagination, which is sometimes used within China to mock President Xi Jinping.

The problem is that this version, like so much else in the popular imagination, is actually owned by Disney via trademark. And trademarks never expire. It’s only the copyright on the character that has gone into public domain, and if you want to get specific, that very British character is actually stylized Winnie-the-Pooh, like Stratford-upon-Avon. This was well understood by the actor Ryan Reynolds, who owns an ad company that is surprisingly adept at responding to current events, and who made an advertisement for Mint Mobile that capitalized on Pooh’s being in the public domain by incorporating it into the text of the book, which is completely fine. You’ll notice that the ad makes no mention of Tigger because, as many pointed out about Blood and Honey, he was not introduced by Milne until 1928, and therefore has at least a year of copyright protection on top of the Disney trademark.

I’d guess that the makers of Blood and Honey might not have given this enough thought, and that a note from Disney’s lawyers accounts for the disappearance of the characters from the trailer. They might have to do reshoots with a redesigned version of the character, as the red shirt and familiar voice are definitely off-limits. Still, you can’t buy publicity like the kind they’ve had and something tells me that this indie passion project will find its funding, bringing to life the director’s unique ideas about murdering women in bikinis.