Art & Tech

10 Predictions About Unexpected Ways A.I. Will Reshape Art (Part 1 of 2)

Get ready for deep symbolic systems, weirdo videogames, and "emotional chaos."

Get ready for deep symbolic systems, weirdo videogames, and "emotional chaos."

Ben Davis

The conversation around the effects of A.I. on art has dominated the year. I probably don’t even need to say that.

The thing is, the effects of Artificial Intelligence on “art” are in many ways not really that important, in the big scope of technology’s effect on the world. I often think that the fate of “art” is something tech giants want people to focus on, because it has more positive—or at least more ambiguous—outcomes than A.I.’s effects on other areas of life (the economy, the environment, the concept of verifiable truth).

Will this technology produce cool stuff? Of course! Can it be an inspiration for good artists? Of course!

Still, the implication of A.I. for art is real terrain that should be critically explored. Refik Anadol is the major star in the world of artists working with Artificial Intelligence. I began my year by reviewing his hulking generative video piece at MoMA, which used the famed museum’s collection to create infinite, woozy new images out of its data.

Anadol has spoken cheerfully about how his inspiration for such generative artworks was Jorge Luis Borges’s short story The Library of Babel, with its vision of an infinite library that permuted language into every possible combination. But the explicit moral of that story was that, once society fully realizes the implications of such a situation, all sense of meaning collapses and humans commit collective suicide. So I think to myself, “the level of intellectual discussion here is low.”

“Refik Anadol: Unsupervised” at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Ben Davis.

I always say: Futurology is mainly people telling you what corporations are already doing. Here, I’m trying to avoid predictions like, “art gets more interactive” or “limitless content-on-demand,” because obviously that is just restating the proposition generative A.I. is being sold on. Last year, I wrote an essay called “A.I. Aesthetics and Capitalism,” in my book Art in the After-Culture. That book came out before the big wave of generative A.I. defined by Dall-E and the like—but the basic approach I lay out in it, it seems to me, is more relevant than ever.

The main point is that “art” is defined socially and not formally. Trained on the vast sea of images on the internet, A.I. art generators spit out things that have a lot of the formal qualities of things we like to look at, and that are called art. But whatever can be done easily with the technology is not what is going to be recognized as “art,” because art is by definition the exceptional case of something, not the default. If A.I. generators make, say, writing in rhyming verse or calling up optical illusions one-click easy, then those forms have been trivialized.

A consequence of this framework is that, if you want to predict the future of “art” in the shadow of generative A.I., you specifically do not want to focus on what the technology makes it easy to do. You want to focus on what it doesn’t do, or what remains difficult to do, because it is in that direction that our understanding of “art” is being pressed. (Of course, various lawsuits and activism may force changes in these tools that alter the terrain, as emblematized by the writers and actors strikes of this year.)

And that is a daunting task for the imagination, because the technology that has rapidly become ubiquitous in the last year and a half does a lot very impressively. But here are some very speculative thoughts on how A.I. might be rewiring the perception of art in general.

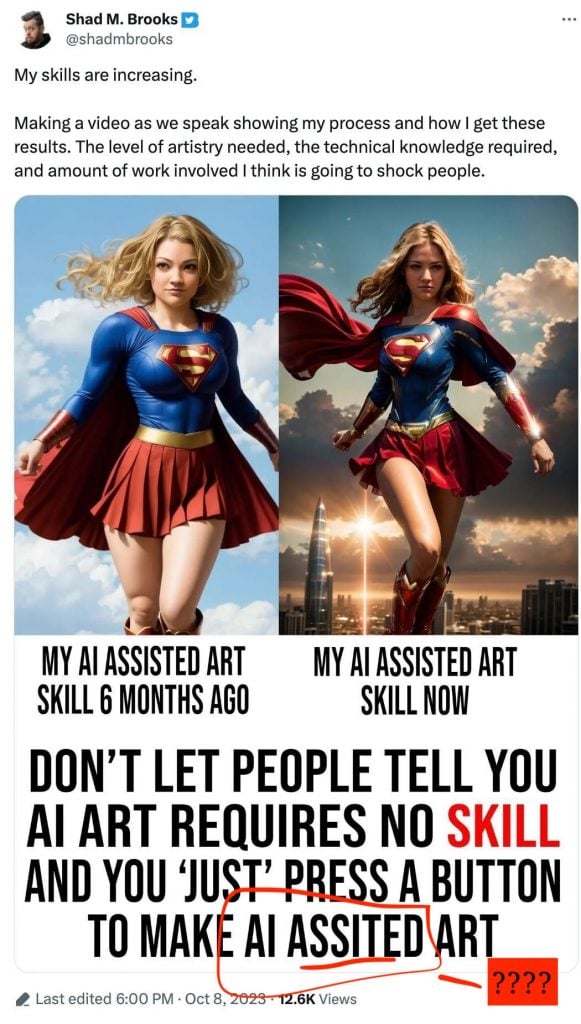

Shad M. Brooks evangelizing his mastery of A.I. art.

The lowest version of “A.I. art” is just the images spit out by A.I. image generators—although the very accessibility of these generators is what has made the subject of “A.I. Art” such a white-hot topic. With minimal effort, anyone with an internet connection can pump out pictures that look like artworks that would have required some sophisticated illustration skills just a little while ago.

This fact has injected a strange, sometimes delusional, probably temporary euphoria into the recent conversation. One Shad M. Brooks briefly became an object of widespread ridicule in digital illustration circles back in October by bombastically claiming to disprove the idea that A.I. art required “no skill.” To show the wizardly level of talent he had achieved by mastering A.I. tools, he posted an image of his wife as Supergirl. The image looked… like a generic A.I.-generated image of Supergirl.

The internet is being flooded with low-effort A.I. junk, trying to capture your attention with the least possible effort. Since the impression of general artistic coherence can be generated easily, but it still takes effort to nail down all the details, you’d expect the audience to develop new sensitivities to the kinds of details that suggest some sustained thought has been put in—that is, if we are talking about any image that people are going to treat more seriously than clipart. (In the infamous Shad M. Brooks example, you don’t have to look that long to see that the light sources are very odd and Supergirl’s head is ginormous.)

Of course, A.I. image-generating tools are getting better aggressively. The mangled hands that characterized last year’s crop of A.I. illustrations are already ancient history.

But in all cases the law holds that something that is low-effort will sooner rather than later be viewed as “low-effort” by the audience. The pressure to show that a unique thought process suffuses an image down to its details is going to go up and up.

Left: Albrecht Dürer, Melancholy I (1514); right: a Midjourney interpretation of an allegory of ‘Melancholy’ in Dürer’s style.

Following on from this, I would expect much more art to focus on detailed symbolic systems, to cut against the sheer impression of visual arbitrariness that these tools encourage.

Maybe what stands out is something much more like medieval allegory, where everything is expected to not just look like a real thing, but to suggest an underlying plan of meaning that you are meant to discover throughout.

Compare Albrecht Dürer’s famous engraving Melancholy I (1514) to my image produced with Midjourney inspired by it. Every item in the former has a specificity meant to convey a meaning as part of a specific Christian mystical worldview: the star, the ladder, the compass, the “magic square,” the polyhedron, etc. That’s part of its poetry—even if Dürer’s final meaning has remained somewhat obscure.

The Midjourney image does look startlingly, even delightfully Dürer-ish. But instead of suggesting a program of meaning, all the details—the mutant animal skulls, the multiple alien globes, the starburst/clockface in the background—read as clutter. When you try to decode the thought beneath them, what you will end up decoding is how imprecise and low-effort my instruction for it was: “make me an allegory of ‘Melancholy’ in the style of an Albrecht Dürer engraving.”

With time and intelligence, you can make the A.I. generate more precise things—that’s the craft of it. The point is that the ease of generating superficial visual elements might mean that the demand on the symbolic model-making beneath them gets cranked up, so that the premium on specificity and resonance of all the parts as a system intensifies.

A gamer plays the video game Red Dead Redemption 2 on January 9, 2019. (Photo Illustration by Chesnot/Getty Images)

In general, however, generative A.I. definitely trivializes the production of individual digital images. I would say that individual images are not really where it is at.

People care a lot about whether A.I. is used when it comes to artisanal objects, because those forms exist to preserve specific forms of making; that is part of their value proposition. On the other hand, people don’t care about human touch in videogames, which are the single most popular, advanced, and highly capitalized wing of the contemporary culture industry. Videogames are “born digital.” The world-building sophistication and immersive quality that makes them so captivating is unimaginable without some form of A.I.-powered creativity in the first place.

“The era of reproductions seems to be over, more or less,” the legendary German art filmmaker Harun Farocki said, already some years ago, “and the era of construction of new worlds seems to be somehow on the horizon—or not on the horizon, it is already here.” He was speaking about his final opus, a video essay on videogames as modern myths, but the advent of widely accessible generative A.I. makes the quote even more resonant.

There is definitely art that plays with the form of the videogame—but not nearly as much as you’d think given how massive they are as a cultural form. As A.I. collapses the skill levels that go into programming as well as image-making, you’d really expect a convergence of indie games and art, and many more works that look like weird, idiosyncratic art-videogames, ultimately breaking free of the low-fi aesthetic that has dominated the “art game” genre up until now.

Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring (1665), evolved through six iterations of the prompt “make it more beautiful,” with Midjourney.

The “Make It More” A.I.-art meme of this year, where people took an initial image and then asked Dall-E to “make it more X” until it achieved its most absurd and extreme form, seems to me to be a metaphor for the visual environment’s entire direction of travel under the technology’s influence. (That’s my low-effort try with Girl With a Pearl Earring, above.)

Desire is piqued by what is out of easy reach. What a desirable image is, then, is almost always going to be pushed towards whatever is rare to see or difficult to generate—and you can generate an awful lot with just a couple of clicks and absolutely no specialist knowledge right now, creating rapid saturation.

The problematic cases that the big Gen A.I. platforms want to limit, in order to defend the honor of the technology—disinformation, gore, harassment, offense, pornography—are naturally where interest is going to flow, as users generate more, more, more of every other desirable content category, and these mutate towards their most attention-grabbing forms.

And, clearly, the technology is ultimately uncontainable. Users are finding ways to make NSFW content—deep, wide galaxies of it. As the obvious forbidden niches (e.g. celebrity pornography, violent fantasies about political foes) get saturated, that, in turn, is going to nudge the cultural environment to the outward bounds of taboo and extreme content, which will then combine and recombine to generate hyper-niche new fetish areas.

A.I. interactive portrait debuted at Focus fair at Saatchi Gallery, October 4-7, 2023. Photo courtesy of Jesper Eriksson.

This prediction may not be an obvious in terms of what it might look like, but it’s still worth talking about.

Art is expressive, so a change in how emotions are expressed is a very real concern for the field. And not just on the thematic level. A lot of media focus has been trained on the dangers of A.I. misinformation, the possible collapse of the ability to discern what is real. But it equally seems we are going to be surrounded by artificial agents emulating emotional encounters with us. That is going to change what people perceive as emotionally authentic.

For one thing, you have to calculate that, because we live in an extremely consumerist world, the vast majority of A.I. personalities you encounter will be the equivalent of corporations putting on a human skin-suit, to try to sell you something. It’s going to be a lot of A.I.-bot customer support, calculated to use the exact right emotional words, but to the end of blocking you from getting a refund on that ticket.

My guess is that some degree of “expressive agnosia,” i.e. the failure to automatically connect emotional cues to their underlying emotional reference, is probably a condition that a society awash in A.I. emotional manipulation encourages. At any rate, you would expect a lot of art exploring the difference between the outward signs of an emotion and its underlying meaning and motives.

Read the second part of this essay, here.

More Trending Stories:

Art Dealers Christina and Emmanuel Di Donna on Their Special Holiday Rituals

Stefanie Heinze Paints Richly Ambiguous Worlds. Collectors Are Obsessed

Inspector Schachter Uncovers Allegations Regarding the Latest Art World Scandal—And It’s a Doozy

Archaeologists Call Foul on the Purported Discovery of a 27,000-Year-Old Pyramid

The Sprawling Legal Dispute Between Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev Is Finally Over