Art World

9 Surprising, Macabre, and Illuminating Books for Art Lovers to Read Over the Holidays

From tales of great but irate artists to a mini compendium of teeny-tiny artworks, these books will thrill on the beach or by the fireside.

From tales of great but irate artists to a mini compendium of teeny-tiny artworks, these books will thrill on the beach or by the fireside.

Sarah Cascone

Given that this year’s holiday calendar has resulted in a blissfully long break for many people, now is the time—maybe, depending on how accelerated your lifestyle has become in the modern era, the only time—to delve into a great art read. The artnet News team’s picks range from novels where art is a subplot to rip-roaring dramas about artist protagonists to biographies of real-life muses.

Happy holidays, and happy reading!

A case study on the artist as tortured genius, The Italian Teacher doesn’t tell the story of the great Bear Bavinsky, a celebrated portraitist of naked women who eschews the market, holding out for a place in the world’s great museums rather than on the walls of monied collectors. Instead, it follows the artist’s son, Pinch, as he struggles to carve a place for himself in his larger-than-life father’s shadow.

Bear became an overnight sensation thanks to a 1953 Life magazine story—not so much for the critical praise heralding him as “tomorrow’s action painter, conjoining twentieth-century dynamism with classical forms,” but for the reflection of his female model’s nipple, unwittingly included on the magazine’s cover photograph of the artist at work in his studio.

Distrustful of the market, which adored his expressionistic “life-stills”—portraits that honed in on a single body part—Bear becomes increasingly reluctant to show anyone his work. Then a series of events leaves Pinch to take control of his father’s legacy, in the unlikeliest of ways.

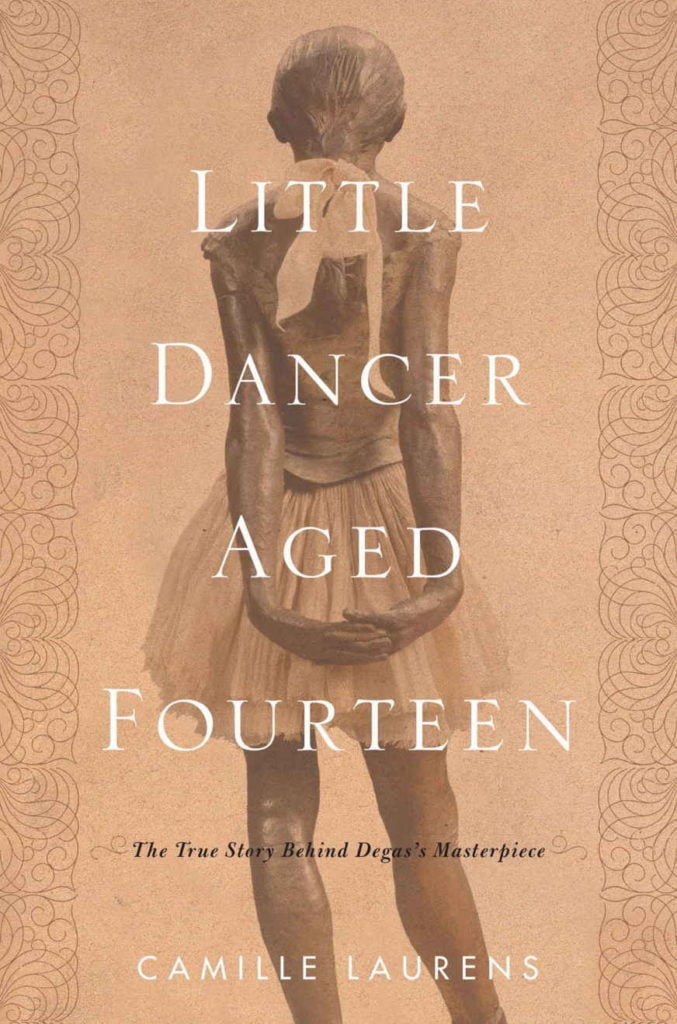

At the “Impressionist Exhibition” of 1881, Edgar Degas debuted a tiny statue of a teenage ballerina to mixed reviews. Since the work has now become one of the most famous sculptures in the world, it’s difficult to appreciate just how revolutionary it was to audiences at the time, achieving near-uncanny-valley status with the realism of its wax skin, human hair, and cloth garments. Even more shocking to the aesthetes of Paris, however, was the subject itself: one of the “little rats” of the opera, young girls in training to join the corps de ballet.

In this book, author Camille Laurens takes a deep dive into the seedy world of the Parisian ballet, uncovering the sad, hard lives of the mere children working long, hard hours with little chance of escaping the vicious cycle of poverty and, all too often, prostitution. It was one of those little strivers, Marie Genevieve van Goethem, who achieved immortality as Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen.

Marie’s life, small and seemingly insignificant though it might seem, is just as much the subject of the book as the work she inspired, with Laurens tracking down every possible mention of her in the historical record. Sadly, however, very little information about Marie has survived, offering only tantalizing glimpses into the real girl who lay behind the proud, bold sculpture that found a place in the art history text books.

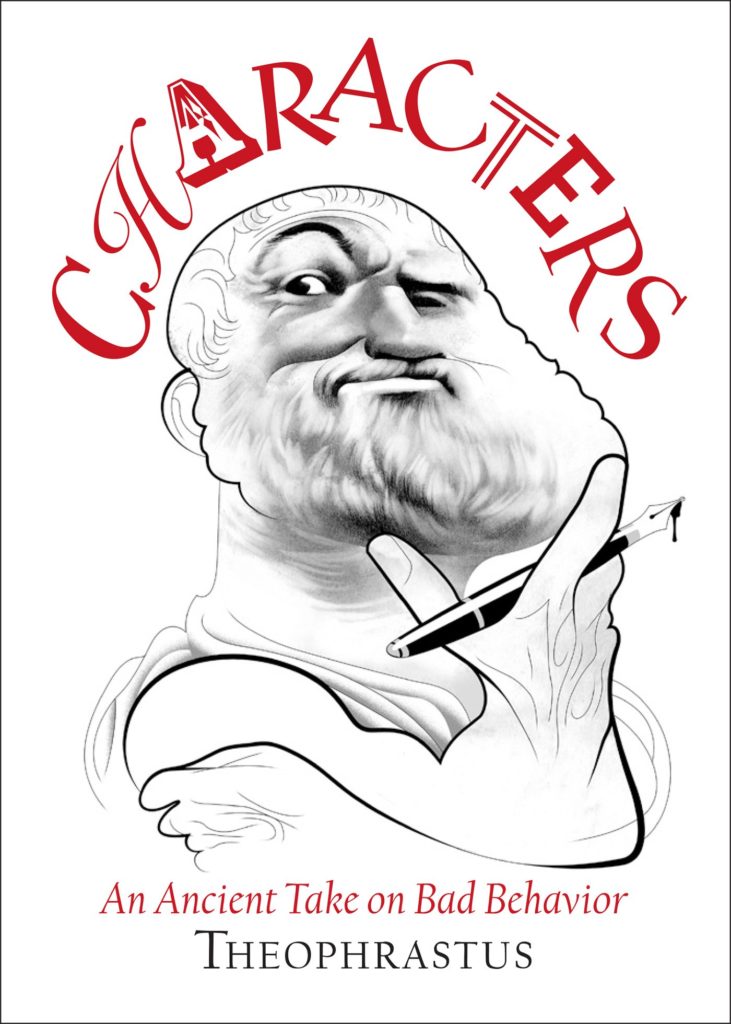

Artist Andre Carrilho breathes life into an ancient Greek classic with his delightful illustrations of Theophrastus’s ancient text, which breaks down common human flaws into 30 characters. Each drawing perfectly captures the inherent ugliness of such societal archetypes as the busybody, the social climber, the coward, and the flatterer.

The text is remarkably timeless, demonstrating that mankind’s faults resonate across 23 centuries—and there are also constant reminders that this wasn’t written about the ugly Americans of the 21st century but ancient Athenians (with helpful annotations by classicist James Romm). Take, for instance, the instantly recognizable miser: “at a communal supper, he keeps count of how many glasses each man has drunk, and then the initial libation he pours to Artemis is smaller than that of any of his fellow diners.” What a jerk.

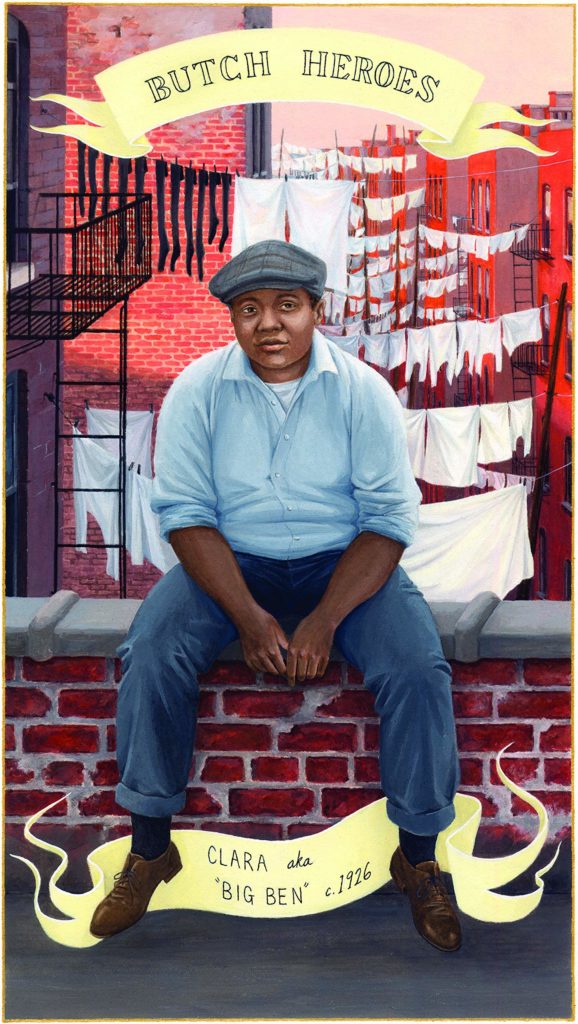

In the works since 2010, Butch Heroes is equal parts art project and history book, with the artist and author Ria Brodell uncovering the personal lives of 28 historical women who refused to conform to gender norms, reaching back as far as the 15th century for incontrovertible evidence that gender fluidity existed long before there was a name for it. This research, Brodell explains in the book’s intro, “requires reading through the lines because so much of queer history has been explained away as illness, romantic friendship, opportunistic cross-dressing, or fraud.”

Sadly, many of the tales Brodell has unearthed have unhappy endings—most of these non-conforming women made it into the historical record by attracting the attention of legal authorities, who never knew quite what to make of them. But while Catharina “Anastasius” Linck, who married a woman, was beheaded for sodomy in Prussia in 1721, there was also D. Catalina “Antonio” de Erauso who fought for Spain in the New World, successfully petitioning the pope to live as a man and receiving a government pension in the 1600s.

Appropriately, Brodell has memorialized her subjects with poignant portraits, painted in the style of Catholic holy cards of the saints, recognizing and honoring their inherent dignity as she writes LGBTQIA individuals back into the history books.

The conceit of Noah Charney’s latest book is a rather elegant one: over millennia, so many great artworks have been lost or destroyed that, were they to be somehow recouped, they would easily fill a museum to rival the world’s foremost institutions. From infamous cases of art theft, like the 1990 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist in Boston, to wartime looting and devastating fires, the author rehashes various acts of art historical loss with gusto.

It reads like a little bit of a laundry list of artworks at times, but Charney does draw out some interesting stories from the annals of art history that even the dedicated aficionado might not be familiar with, making it clear that our understanding of artistic heritage has been shaped by forces beyond our control.

Did you know, for instance, how close we came to losing Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas to in 1734, when the Royal Alcázar palace in Madrid went up in smoke? Such narrowly averted disasters make you wonder how well lost masterpieces would stack up to the existing canon, and invites speculation as to how modern technology might someday begin to replicate art historical treasures heretofore presumed to be lost forever.

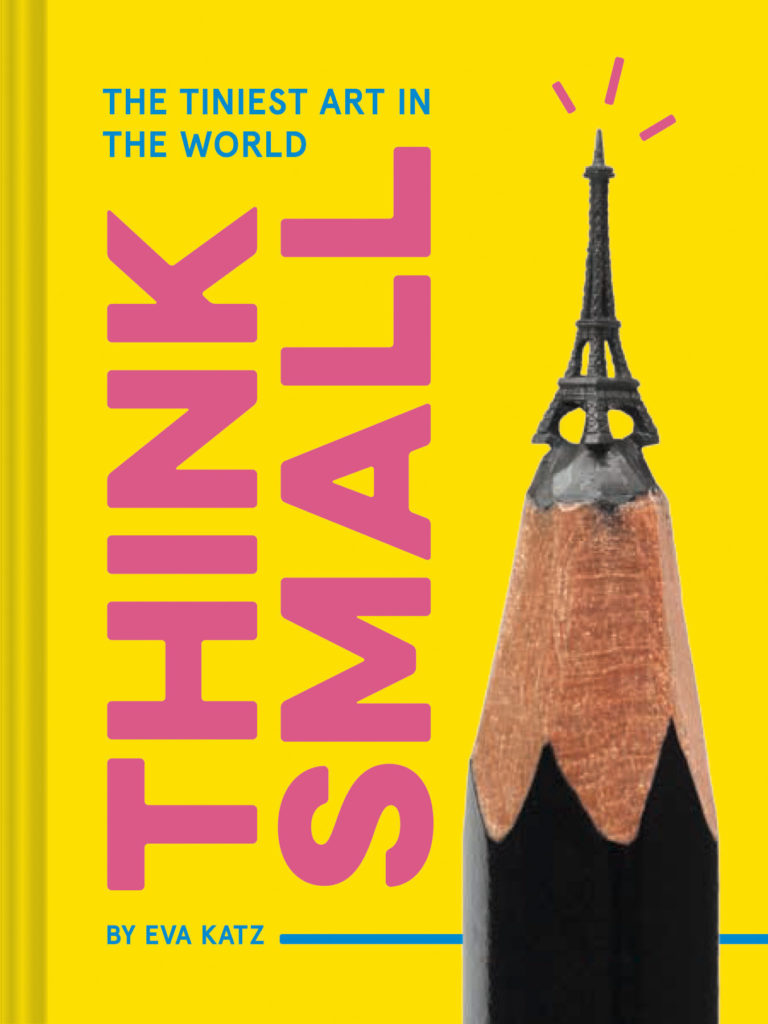

Marvel at the extreme dexterity and patience of 24 contemporary artists who painstakingly labor to create artworks at minuscule scale in this adorably tiny coffee-table book. From Hasan Kale, who somehow turns halved almonds and matchstick heads into canvases, to Salavat Fidai, who carefully carves pencils into tiny lead sculptures, each diminutive piece offers mind-blowing demonstrations of craft, skill, and artistic vision.

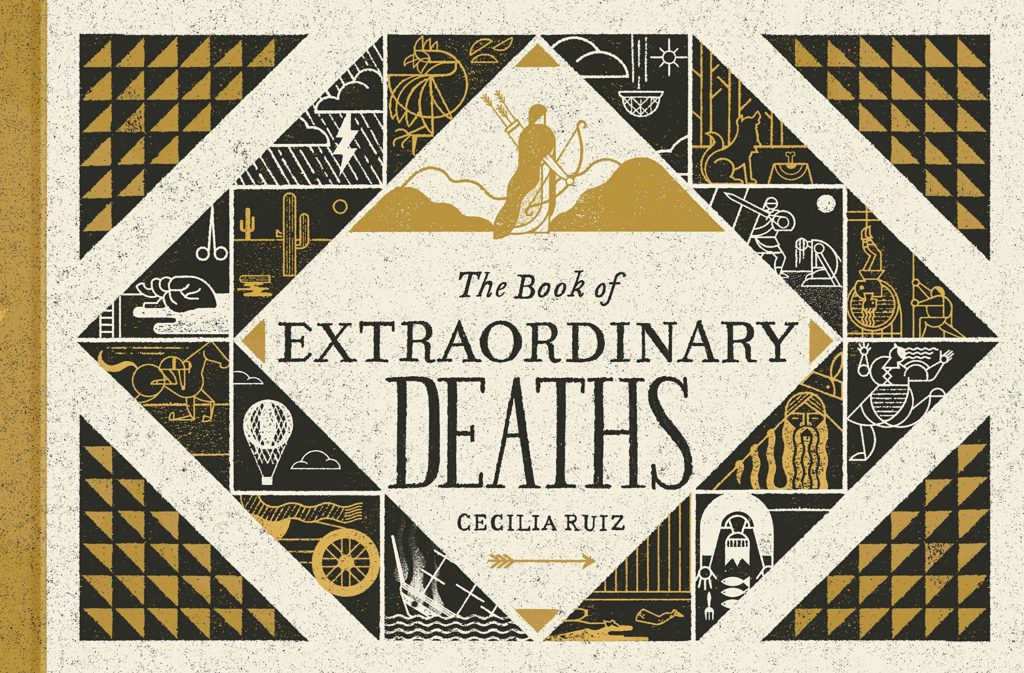

This quirky, playful, amusingly macabre artist’s book is exactly what it sounds like: Cecilia Ruiz has collected history’s most bizarre demises and illustrated them.

There’s George Plantagenet, who in 1478 is said to have chosen to die by drowning in a barrel of wine after he was sentenced to death for plotting against his brother the king. Of more recent vintage, in 2011, cock-fighter Jose Luis Ochos died when one of his roosters stabbed him with a metal spur used in the illegal sport. And, in ancient history, the lawmaker Draco allegedly gave a brilliant speech to the citizens of Athens, who then accidentally suffocated him under a pile of coats, hats, and other gifts thrown in admiration.

A beautifully ironic tribute to the absurdity of human life—and death—True Accounts is morbid in all the best ways, and should serve as the perfect antidote to those currently overwhelmed by Christmas cheer.

There are a lot of things to like about A Big Important Art Book by Danielle Krysa, founder of contemporary art website the Jealous Curator. I suspect that the book’s informal, chatty writing style may be hit-or-miss with readers—I found it annoyingly cutesy, but I guess all art writing doesn’t have to feel formal, and it might even make it more accessible for a broader audience.

In any case, we need projects like this to help level the playing field for women artists and to correct centuries of gender imbalance in the art world. Secondly, there is no way you won’t discover a new artist in this book: even for a journalist who often spotlights the work of female artists, only a small handful of the 45 contemporary artists featured here ring a bell.

Krysa has done an admirable job of sitting down with her subjects, sharing the stories of their lives, their artistic inspiration, and their working methods. I didn’t necessarily need to read the artists’ statements, which almost inevitably veer into the realm of incomprehensible art speak, but I’ll definitely keep an eye out for the work of Seonna Hong, Naomi Okubo, and others in the future.

Another thing Krysa has done well is the illustrations, with gorgeous photographs of each contemporary practitioner’s work—which makes the lack of imagery for the historical women artists highlighted in each section all the more galling. I was more familiar with the careers of those women, but I still would have appreciated the visual juxtaposition of Ruth Asawa’s elegant wire-basket forms with British sculptor Ann Carrington’s works made from found materials like buttons and barbed wire.

Glenn Adamson, former director of New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, may have just become the Marie Kondo of the art world with his new book, which makes a case—seemingly antithetical to the ethos of collecting—for owning fewer things and becoming more in touch with our possessions.

The book is a celebration the history of craft, even as it bemoans our increasing dependence on smartphones and other plugged-in devices. (Adamson also highlights the environmental impact of our consumerist culture.) His hope is that, as we pare down our cluttered lifestyles, we can become more in tune with the pleasures of everyday materiality. Consider, for instance, a street in Manhattan, which Adamson considers in extraordinary, exquisite detail:

“Look down, and you’ll see pavement of hot poured and rolled asphalt. It is punctuated by steel manhole covers, which are round, because a square or rectangular cover turned at the wrong angle would drop right into the hole. To make them, a design first had to be carved in wood or machined in aluminum. The resulting pattern was then set into fine and densely packed sand, leaving a very detailed impression, into which the foundry workers poured molten iron….”

It’s hard to imagine engaging with our world this way on a regular basis, but it’s a useful exercise that will make you take a long, hard look at everything you own, consume, and possess.