Art World

Here Are the 10 Absolute Best Works of Art We Saw Around the World in 2018

From John Akomfrah's gut-wrenching films at the New Museum to Tschabalala Self's homemade bodega in Shanghai, here's the art we'll remember most.

From John Akomfrah's gut-wrenching films at the New Museum to Tschabalala Self's homemade bodega in Shanghai, here's the art we'll remember most.

Artnet News

There’s a lot of art out there. A lot of it is notable in the moment, but doesn’t necessarily stick in the mind. Then there’s that show—or that individual work—you can’t forget. Below, our editors pick the most memorable, exciting, and enchanting art they saw this year.

Bruce Nauman, still from the seven-channel video Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (2015-16). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York

A seven-channel video that lines a gallery’s walls like a moving frieze, Contrapposto Studies, i through vii presents footage of Bruce Nauman walking through his studio with his hands above his head, swiveling out his hips as he walks to create the s-shape of the contrapposto figure in classical art. On the bottom row of the first sequence, you see several shots of the artist walking in this manner, while on the top row you see the negative footage of the same action. From sequence to sequence, however, changes occur to accentuate the idea of contrapposto—the legs go one way, the torso another; then the knees go one way, the thighs the other, and the waist the other. It’s both essentially simple and profoundly complex, in that classically Naumanesque way. (Speaking of classics, the work is a sequel of sorts to the artist’s landmark 1968 video Walk With Contrapposto Suite, which my colleague Eileen Kinsella hates.) I first saw Contrapposto Studies when it was debuted at Sperone Westwater in New York in 2016, then again at the Schaulager in Basel this June, then again at MoMA in the fall, and each time it seemed to grow in profundity—a meditation on the ineffable binaries of our strange universe, mind and body, darkness and light, inverse and obverse, old and new. It’s Nauman’s latest masterpiece, and one of his greatest.

—Andrew Goldstein

Still from Marianna Simnett’s The Udder (2014).

There are those works of art you block out time on your calendar and take a lengthy subway ride to see. And then there are the ones you encounter by accident. I happened upon this exhibition of the young UK-based artist Marianna Simnett toward the end of a recent visit to the New Museum—but once I sat down to watch her twisted, haunting video The Udder, I had to change my dinner reservation because I wasn’t prepared to leave. The entire film takes place inside the mammary gland of a cow, where children and their dairy farmer parents are separated by gauzy red walls. Everyone is very concerned that youngest daughter is going to go outside and somehow become contaminated. I know—it sounds somehow simultaneously confusing and overwrought. (Purity! The body! We’re all just animals!) But it’s actually one of those works of art that manages to make otherwise trite ideas feel urgent and twisted and new—like a not-quite-nightmare you can’t get out of your head for days.

—Julia Halperin

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation (2012). Courtesy of Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

At the 2015 Venice Biennale, John Akomfrah’s film Vertigo Sea (2015) was an unsettling revelation. This extended dirge for the costs of human conquest—made most explicit in an extended and nauseating scene of whalers destroying an animal—set the tone for the rest of the violent exhibition. By contrast, The Unfinished Conversation, which offers a refracted vision of the life of Jamaican-born, British philosopher Stuart Hall, is a quieter, but no less impassioned film. “Another history is always possible”: this quote of Hall’s is the foundation for Akomfrah’s work, which pictures the theorist and the development of his ideas through fits and bursts of historical footage of life in Britain. Here’s Akomfrah at his best, collaging clips to make them pulsate with radical possibility.

—Pac Pobric

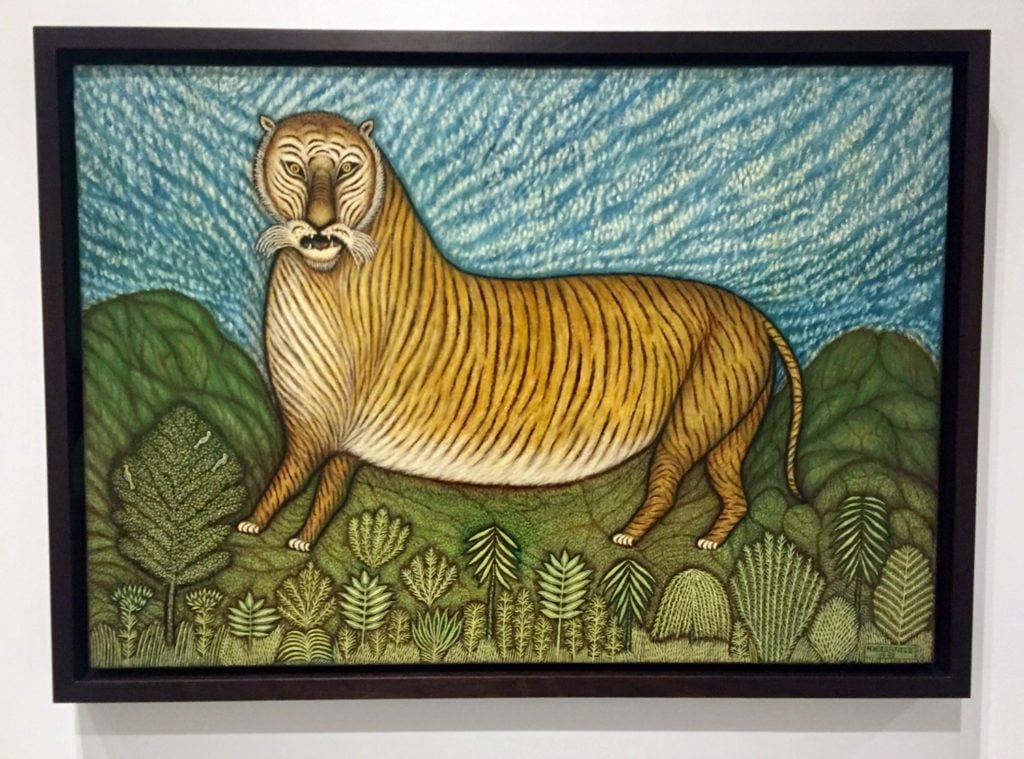

Morris Hirshfield, Tiger (1940) in “Outliers and Vanguard Art” at the National Gallery of Art. Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

“Outliers” was one of the museum events of the year, and almost fascinating because it felt so unresolved, reaffirming the distinction between “folk” and “fine” art at the same time that it sought to flatten it. In any case, I love this painting. “Among American artists,” MoMA’s founding guru of modernism, Alfred H. Barr once said, “I do not know… a more unforgettable picture than Hirshfield’s Tiger.” You know what? This unwieldy, magical, but seemingly fully realized beast is absolutely winning, and has taken up permanent pasture deep in my mind.

—Ben Davis

I loved Tschabalala Self’s transformation of a room at Budi Tek’s Yuz Museum in Shanghai (part of the artist’s first solo show in China) into a typical neighborhood bodega, complete with those distinctive colored-check tiles and even a scrappy bodega cat. But “Bodega Run” also offers a deeper look at economic disparity. The drawings, sculptures, and paintings here look at the processed, unhealthy food that visitors buy with their food stamps, as well as the lack of nearby supermarkets offering healthier alternatives. These family-run corner stores emerged with the arrival and settlement of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans to New York City and have become “a social space where different communities of color converge,” according to a statement from the Yuz.

—Eileen Kinsella

Paolo Pivi, World Record in “Paola Pivi: Art With a View” at the Bass, Miami Beach. Visitors enjoying the installation include Creative Time director Justine Ludwig, third from right, and the artist herself, second from left. Photo by Attilio Maranzano, courtesy the artist and the Bass, Miami Beach.

Anyone who has visited Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach will tell you that it is a nonstop whirlwind—which is perhaps why, after 30 seconds of lying on my belly atop one of the 80 mattresses that make up World Record, a sculpture-meets-audience-activated performance in Paola Pivi’s exhibition at the Bass, I had announced to all those around me that this was my favorite artwork, ever.

Little did I know that Pivi herself was among those lounging on the comfy installation, which I quickly likened to the world’s largest pillow fort. She envisioned the work as a protected space, a floor and ceiling of mattresses offering “padded white peace,” as per the exhibition label—a place where adults might play like children.

What I found was an immediate sense of relief, the stress of the day melting off my shoulders as I collapsed against the cushions. The sound was oddly deadened as I spoke to the other people sprawled out on the mattresses. The soft, springy surface seemed to stretch on forever, creating a world without responsibility or consequences.

I wanted to stay there forever, enveloped in the sense of joy and community Pivi had created, safe from the chaos of the fair and deadlines. Sadly, reality came calling all too soon, but those five minutes of bliss made my week, and maybe even my year.

—Sarah Cascone

Giotto’s Lamentation of Christ (ca. 1305) at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

Some art belongs to a place. Making a pilgrimage to a faraway destination to see art you can’t see anywhere else because it belongs to one particular set of walls can be rewarding in ways that traditional museum shows just can’t. My first visit to Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy, this past spring was something like seeing the cave paintings for the first time, a quasi-transcendent experience where entering the chapel also meant crossing a threshold into another time and cosmos. And yet Giotto’s wailing angels, flattened against that perfect blue sky, heads flung back at the sight of Christ’s dead body below, seemed to be imploring me, directly, to see their sorrow. It’s rare today to encounter art that can bring you to tears, and while that shouldn’t be a measure of greatness in itself, it’s amazing when it does happen, especially in a context that’s centuries away from home.

—Rachel Corbett

Video still of Mario Pfeifer’s Again / Noch einmal (2018). Courtesy of Mario Pfeifer, KOW, Berlin, copyright 2018 VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

In 2016, German “vigilantes” beat and dragged an Iraqi refugee out of a grocery store and tied him to a tree. News of the incident, which went viral, was quickly dismissed by the courts and the refugee went missing and later died. In Mario Pfeifer’s two-channel video, which debuted at the Berlin Biennial this summer, the East Germany-born artist reconstructs the situation and creates a false trial to reexamine the incident with a jury of real German citizens. Their conclusions and remarks on the nuances of the migrant experience in Germany are harrowing and profound as we see, more and more, history repeating itself. It is rare that an artwork goes a full step beyond the boundaries of the art-world bubble and takes a real stake in the world. This one did.

—Kate Brown

Exhibition view of Simon Fujiwara, Empathy I (2018). Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2018. Photo © Andrea Rossetti.

I was skeptical when I first heard about Fujiwara’s rollercoaster-ride art. I worried that the whole thing was a gimmicky addition to the trending wave of Instagram-baiting art installations but—spoiler alert—I was wrong. (In fact, they confiscated my phone.) After a waiting game involving a numbered ticketing system gave me time to look up at the four moving platforms, I started to get anxious about how involved this “sculptural experience” would actually be. This was heightened by watching windswept visitors emerging two by two from a mysterious box, and then, when my turn came, being asked to empty my pockets before being strapped into the contraption. All in all, very on brand for a space called Lafayette Anticipations.

The actual experience is, of course, more akin to a Disneyland 4D film than a rollercoaster, but my anxiety primed me for the emotional onslaught to come. Through Fujiwara’s video collage of found footage you’re thrust into the first-person perspective in a variety of scenarios and emotional states, dancing at a wedding, jolting over the desert in a four-wheeler, splashing into the ocean on the edge of a raft, the different scenarios flickering out faster than your brain can keep up. It’s over in four minutes, after which you feel like you’ve lived a thousand lives. If you’re a hypersensitive person like me you’ll probably be in tears.

—Naomi Rea

After viewing Vertigo Sea, the gravitational center of the pioneering British media artist John Akomfrah’s exhibition, I left the gallery reeling like a sailor who had just survived a shipwreck. The monumental three-channel video installation manages to take something normal humans are incapable of processing—the relentless, centuries-long campaign by the most powerful of our species to pillage everything outside of themselves for utility, profit, and ego—and renders it visible and visceral.

True to its title, Akomfrah frames most of Vertigo Sea around bodies of water. And while its arc turns on the theme of colonization, the work also surfaces man’s exploitation of plants and animals. It calls out the direct link between, say, sailing to Alaska to shoot polar bears and sailing to Africa to enslave other humans (who can then simply be thrown over the bow of a ship when their perceived usefulness has expired).

At the same time, its images are consistently arresting—a mix of high-production-value filmic setups, top-tier nature cinematography, and brutal found footage. The only thing I can think to compare it to is a nightmare I once had about watching a giant snake engulf me from the toes up: a vision simultaneously too terrible and too remarkable to turn away from until it was over.

—Tim Schneider

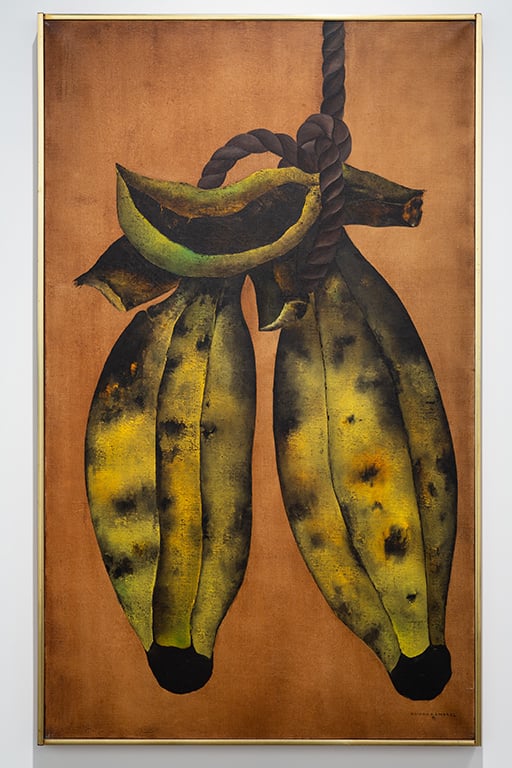

In Sao Paolo for the 2018 Bienal, I had the good fortune of passing through this show, curated by Paulo Miyada. A half century after the infamous “Fifth Institutional Directive” of 1968, which dramatically intensified repression under the Brazilian dictatorship, the show looked at how artists processed the country’s descent into darkness. The subject matter was, of course, sadly freshly topical in the shadow of the ascent of the dictatorship-loving Jair Bolsonaro, and Amaral’s work from his most well-known series of bruised bananas says everything plainly through the elemental devices of its brooding tones and swollen and strangled forms.

—Ben Davis

Adrian Piper, Food for the Spirit #8 (1971, reprinted 1997). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin. Photography by Jonathan Muzikar

Hailing from the period of transition between Piper’s more purely minimal art and her more performance-based practice, Food for the Soul consists of what amounts to a conceptual-art diptych: a grid of self-portraits of the solitary artist receding into darkness, taken in a mirror, paired with a spiral-ringed binder of pages from Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, with Piper’s underlinings and notes in the margins. Puzzled, you ping-pong between the corporeal directness of the photos and the largely illegible, rarified philosophical reflections in her notes, trying to resolve the two threads into one thought.

Then you recall that Kant’s key philosophical term in the First Critique was “antinomy,” “a contradiction between two beliefs or conclusions that are in themselves reasonable,” much the way you feel that the two parts of Food for the Soul run enigmatically parallel here as evidence of her experience, the purely cerebral, the viscerally corporeal—both valid.

And then, after another moment of reflection, this sense of an artwork divided also falls away, as the two sides blur back together: You realize that Piper’s handwriting in the book is evidence of her body present in the process of thinking, while her photo self-portraits, with their disciplined progression and variation, are as vivid an image as any of a consciousness trying to shape its self-awareness. A work that both predicts the contemporary interest in self-fashioning and self-presentation and complicates its premises in advance.

—Ben Davis

INNER COURSE, THE AGONY OF IT ALL (2018). Photo by Laura Dvorkin.

If you haven’t made it to Beth Rudin DeWoody’s private West Palm Beach art space the Bunker yet, you should know that it is every bit as spectacular as you’ve heard. Welcoming visitors during the first-annual New Wave Art Wknd, DeWoody and her curator Laura Dvorkin also arranged to hold a special performance by INNER COURSE, a project from Rya Kleinpeter and Tora López.

THE AGONY OF IT ALL, originally staged at Brooklyn’s Smack Mellon over the summer, sees Kleinpeter and López, outfitted as retro housewives a lá Lucille Ball, in twin beds. Surrounding them is a mountain of outrageously sexist books about women—some well-meaning, others unabashedly misogynistic. They sip wine to console themselves, reading aloud until they break into tears, blowing their noses theatrically and offering visitor tissues.

The piece was hilarious, but also heartbreaking. At first, you think, how ridiculous these books are. Then, you remember that someone took the trouble to write each of them—and some quite recently. These words are a reflection of the attitudes of the patriarchy, still deeply ingrained in our society even in the age of #MeToo. If you or someone you love doubts the continued relevance of feminism, think again.

—Sarah Cascone

Tauba Auerbach, Flow Separation (2018), on the Fireboat John J. Harvey, courtesy of Paula Cooper. Photo by Nicholas Knight, courtesy of the Public Art Fund, New York.

Tauba Auerbach’s Flow Separation, commissioned by the Public Art Fund, succeeded on so many levels. For one thing, it was a sheer visual spectacle: a large ship painted in spectacular swirls of white and red, a design created through the technique of marbling. It also engaged with its environment, bringing New Yorkers who rarely have reason to recall Manhattan’s status as an island out on the water, exposing them at once to nature and the city’s unparalleled skyline. And it was a lesson in history, inspired by the dazzle ships of World War I, a counter-intuitive form of bold camouflage aimed at confusing the enemy, invented by British painter Norman Wilkinson.

If you didn’t get to go for a ride on the John J. Harvey, the historic fire ship brought back into service for the project, then you missed a truly special experience. But the boat is docked at Hudson River Park’s Pier 66a through May 12, 2019, so you can still see Auerbach’s work of art for the whole family—something experiential yet beautiful, accessible at first glance and yet layered with meaning. Best of all, it was—and is—free and open to the public.

—Sarah Cascone

Sol LeWitt, Complex Form #34 (1990). Photo by Agostino Osio. Installation view at Sol LeWitt. Between the Lines, Fondazione Carriero, Milan (2017-2018). Courtesy Fondazione Carriero, Milan.

I fell in love with this sculpture by Sol LeWitt when I saw it at the Carriero Foundation. There was just something so special about its placement, bathed in a soft pink light in a nook of the historic Milan building. It was part of a fantastic exhibition for which Francesco Stocchi and Rem Koolhaas were entrusted with curating the works by the conceptual art pioneer.

—Naomi Rea

Eugene Delacroix, The Murder of the Bishop of Liège (1829). Collection of the

Louvre Museum, Paris.

Part of the revelation of the Met’s Delacroix show for me, along with the sheer breadth of the work the artist made, was how powerful the influence of literature was on his work. This scene was inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s novel Quentin Durward (1823), set in the 15th century. Delacroix’s focus here is on the bishop being stripped of his liturgical vestments during an encounter with the villainous. The luminosity of the white tablecloth was meant to create the exaggerated perspective of a divide, since the murder takes place at a banquet, and the anguished faces were meant to recall the furious energy often depicted in earlier French Revolution paintings. The medieval architecture in the background is based on London’s Westminster Hall, which Delacroix visited in 1825.

—Eileen Kinsella