Art World

9 More Thrilling, Poignant, and Satirical Books for Art Lovers to Read Over the Holidays

There's no shortage of exciting new books to crack open this season, from the literary sensation of 2018 to a look at Duchamp's last days.

There's no shortage of exciting new books to crack open this season, from the literary sensation of 2018 to a look at Duchamp's last days.

Artnet News

Looking to bury your nose in a book that can divert you from thoughts of the office, the foibles of in-laws, long airport waits, and other bugbears of the holiday experience? Well, we’ve got you covered—book-covered, as it were. Here are nine more wonderful reads that art lovers of all stripes can enjoy, and profit from, while making the most of their downtime. (Read the first part of this list here.)

In Color Problems, author Emily Noyes Vanderpoel aims “to combine the essential results of the scientific and artistic study of color in a concise, practical manual,” illustrating her explanations of color theory with 116 chromatic illustrations. But there’s a twist! Vanderpoel took on this ambitious task way back in 1901, and her resulting manuscript only returned to print this year, following a Kickstarter campaign.

Informed by the best science of her day, Vanderpoel’s prose holds up remarkably well, and her illustrations look even better—her grid-like compositions and abstract demonstrations of different color combinations seem to anticipate major trends in 20th-century art, such as Josef Albers’s “Homage to the Square” series.

Vanderpoel even offers some possible insight to red’s historic success when it comes to price points, arguing that we are drawn to it because “in nature we have red only in small portions.” (She also quotes liberally from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1810 tome Theory of Colors, offering the poet’s wonderful jab at big-time collectors partial to red: “it is not to be wondered at that impetuous, robust, uneducated men should be especially pleased with this color.”)

—Sarah Cascone

A bright young lady steals the show in The Optikal Illusion, instructing expat American painter Benjamin West, president of the Royal Academy, in the secret techniques Renaissance great Titian used to achieve his peerlessly luminous color. Ann Jemima Provis, just 17 years of age, claims to have gleaned this invaluable knowledge, the so-called “Venetian Secret,” from an old manuscript.

Novelist Rachel Halliburton has seized on a little-known episode in British art history, imagining what went on behind the scenes as Ann Jemima and her father attempted to sell this important artistic knowledge to West and his fellow artists. It’s a captivating tale. (Less engrossing are the power struggles among various long-forgotten members of the Royal Academy.)

A fascinating figure who clearly impressed West, one of the greatest artists of his age, Ann Jemima has left few traces in the historical record. You’ll come away wondering who this young women was, and what might her artistic talent have allowed her to become, were she only born a man.

—Sarah Cascone

A true artist’s book, Karen Green’s Frail Sister is meant to be savored, each page turned slowly, allowing the viewer to take in the rich detail of her collaged narrative, which is told through photos, handwritten letters, and typed manuscripts. An assemblage of found objects and real letters, as well as missives and artworks created by Green—the boundaries between the two are blurry—Frail Sister is an exercise of inventive story telling, creating truly vivid characters with a remarkable economy of words.

The utterly engrossing tale is based on Green’s real life aunt, Constance Gale, a mysterious figure captured only in family snapshots and the odd keepsake. Those remnants became the starting point for the book, which reconstructs the tale of a musical prodigy who served in the USO during World War II, only to disappear upon her return to New York. A beautiful, poignant book that continually surprises, this is one that pushes the boundaries of literature to great effect.

—Sarah Cascone

Any art world denizen who picks up this book will immediately spot the telltale signs underscoring the fact that Celestial, one of two main characters, is a “hot” artist on the verge of a major career. Not only has she been included on a list of “Artists to Watch” in an unnamed glossy magazine, her husband Roy is planning to do serious business by managing both the high and low ends of her art-making.

“Is it true that people pay $5,000 for one of your dolls?” asks her mother-in-law. Roy, one of her biggest fans, writes: “Even before you knew she was a genius with a needle and thread, you could tell you were dealing with a unique individual.” It was excuse enough to delve into this riveting novel about newlyweds with a bright future ahead of them, who are suddenly torn apart by a tragic event. The story muses on the strength of the marriage bond as its characters grapple with forces beyond their control.

–Eileen Kinsella

The latest tale from the author of the The Art Forger is another historical thriller about art and desire that meshes real characters with imagined ones. Paulien Mertens flees to France and assumes a new identity after she is accused of helping her fiancee steal her family fortune, including her father’s beloved art collection. When she finds work with an American art collector and starts rubbing elbows with a circle of famous writers and artists in 1920s Paris, she begins plotting her revenge. It’s a gripping tale that pulls the reader from page to page, offering up Easter eggs of art historical references that will delight anyone who ever pored over a Janson’s.

–Eileen Kinsella

Though he was largely forgotten after the end of World War II, in the beginning of the 20th century Stefan Zweig was one of the most popular and prolific writers in the world. The Austrian Jewish novelist and playwright was at the heart of Europe’s arts and culture scene and, in The World of Yesterday, Zweig describes the situation of celebrated writers and artists he knew through the devastation of World War I and then the rise of Hitler. With a writing style that is clear and lyrical, Zweig’s memoirs are bewitching, entertaining, but also disconcertingly relevant to the Europe I find myself living in today.

It begins in a decadent and enlightened 20th-century Europe, what he calls “a world of security.” Zweig describes the goings on in Vienna, Berlin, and Paris—and, with incredible fervor, the experience of meeting Rodin in his studio for the first time, a man who would become his friend, as well as his friendships with Rilke and Freud. Then, it all begins to crumble before his eyes, as Europe splits off into nationalist factions and the right wing grows in power. He describes the helplessness of the cultural milieus of Europe in the face of it all. “Art can bring us consolation as individuals,” he writes, “but it is powerless against reality.”

It’s a gripping and truthful story of tragic beauty that he wrote from exile in Brazil. Zweig, whose popular books became banned (burned and forgotten) by the Nazi party, had to flee the continent. Very shortly after he finished these perfectly executed memoirs, Zweig and his wife committed suicide.

– Kate Brown

I had no idea that My Year of Rest and Relaxation, acclaimed fiction writer Otessa Moshfegh’s second novel, had any sustained interaction with the art world when I picked it up. I’d just decided I was all-in on anything she wrote after I read Ariel Levy’s mesmerizing New Yorker profile on her and listened to Moshfegh casually destroy ace interviewer Isaac Chotiner on his I Have to Ask podcast. Still, the book exceed my expectations, partly because it incorporates a satirization of the contemporary art world that is simultaneously as brutal, glint-eyed, and casual on the page as her evisceration of Chotiner was in front of the mic.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation is a first-person account of an unnamed narrator’s attempt to medicate herself into a full year of sleep (or at least, as much of a year as she can manage via the deluge of downers prescribed by a quack psychiatrist she finds in the phone book). The question of whether this is actually a way to slow-walk herself into oblivion—assuming any of her narration is reliable in the first place—provides the novel’s central tension. But her journey ultimately hinges on her past as a staff member at a fictional Chelsea gallery, as well as her calculated willingness to serve as muse to Ping Xi, a rising-star artist who makes Dan Colen and Damien Hirst look like maestros of subtlety. Thanks to its haunting resolution, the novel adds up to more, but the narrator’s summation of the Xi’s work also doubles as a fitting epigraph for this year in the art world: “It was all nonsense, but people loved it.”

–Tim Schneider

This essayistic investigation written by the US artist and writer Donald Shambroom dives deep into Marcel Duchamp’s final 24 hours. It centers around a long-lost photograph taken by Man Ray (Duchamp’s closest friend) of the artist shortly after he passed away in October 1968, which is reproduced publicly in Shambroom’s book for the first time. The author asks whether we could possibly see this image as a final collaboration between the two artists, advancing arguments based on a joking remark Duchamp made at a dinner party earlier in the evening about works made in the space between “anthumous” and “posthumous.”

It doesn’t seem that outlandish to suggest that the man behind the “readymade,” who in his life suggested that “each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere,” and who carried his epitaph—”It is always the others who die”—around in his pocket throughout his later years, might have had greater plans for his own passage from life to death. Whether or not Duchamp participated in this final work, if it’s to be considered an artwork rather than a historical record, is an open question. Fifty years after the happening, could his own death be considered one last Dadaist provocation? Either way, the conceptual master who was forever chipping away at the boundaries of what could be considered art probably would have enjoyed the question.

–Naomi Rea

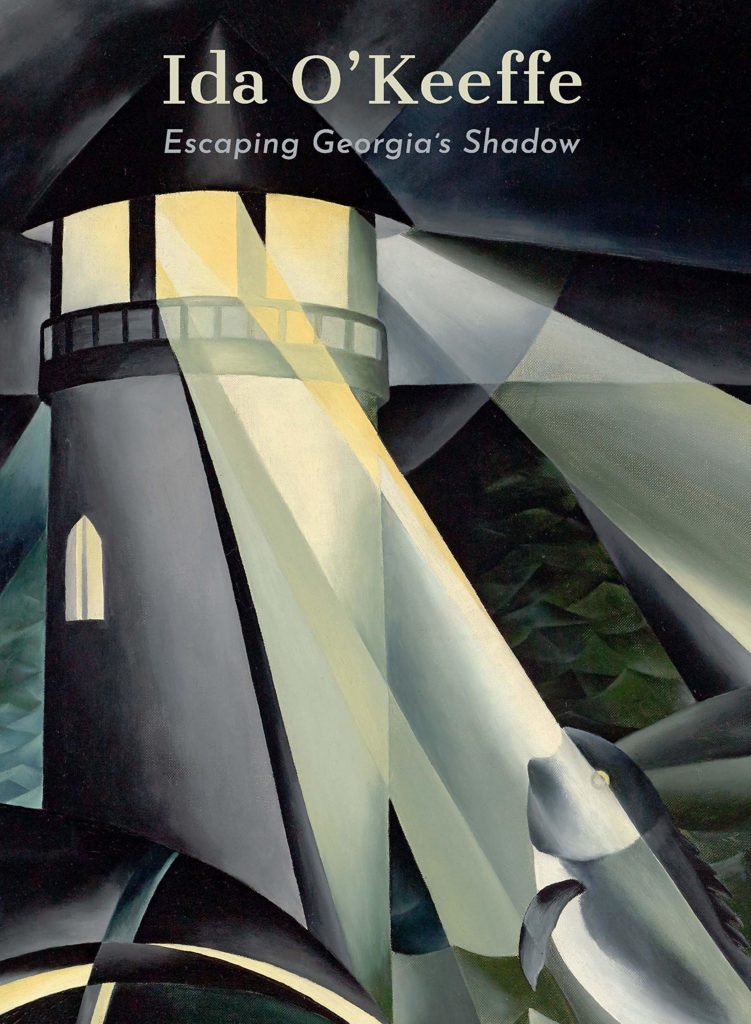

Artist, poet, author, anthropologist, teacher, and professional nurse Ida O’Keeffe had energy and many talents, but it was her misfortune to have a famous older sister who was less than generous in her support. Georgia’s affections for her favorite sibling cooled, it turns out, when Ida began to exhibit her art and receive positive reviews.

If only Ida had had a gallerist like Alfred Stieglitz to back her, as the photographer and dealer did for Georgia, his lover. Instead Ida had to dodge the amorous attentions of “Uncle Al,” who recognized her talents. Having lived constantly in the shadow cast by Georgia, Ida is finally getting the attention she deserves thanks to Sue Canterbury, associate curator of American Art at the Dallas Museum of Art, who has organized a major survey of her work, which is accompanied by this scholarly publication.

Canterbury’s detective work has resulted in the rediscovery of many paintings that disprove any idea that Georgia was the only talented artist in the remarkable O’Keeffe family. She was the third of seven children who grew up in straitened circumstances. Trying to launch her professional career as an artist during the Great Depression was always going to be a challenge. Although the cards were stacked against Ida, Canterbury reveals her to have been a strong and independent woman who had her own artistic voice and never succumbed to self pity or jealousy.

Ida O’Keeffe was rightly proud of her “Lighthouse” series of dynamic and expressive canvases inspired by a trip to Cape Cod and started as a student at Columbia University. Combining Vorticism with Precisionism, the strongest works in the series hold their own alongside work by her American contemporaries, including her older sister’s landscapes. A peripatetic life moving between temporary nursing and teaching jobs across the US hampered her career as an artist. Without an annual solo show in New York, or automatic inclusion in group exhibitions (which Georgia enjoyed), Ida’s potential was never fully realized. Talent and ambition don’t necessarily ensure success and acclaim for an artist in their lifetime, then and now. Having a more illustrious sibling and lacking a powerful supporter to promote her work meant Ida could never escape Georgia’s long shadow.

–Javier Pes