Art World

Here Are 6 Big Ideas That Gripped the Art World in 2018, From ‘Platform Capitalism’ to ‘Chthulucene’

As we look back on 2018, here are a few new terms, concepts, and trends that resonated with the art world this year.

As we look back on 2018, here are a few new terms, concepts, and trends that resonated with the art world this year.

Ben Davis

What new ideas started to creep into art this year? What terms began to insinuate themselves into the critical lexicon?

These are not easy phenomena to track. Some concepts take over the conversation so suddenly that you almost forget how recent they are; some gather cult cachet over long periods before the big tastemakers notice; some have already been played out and exhaustively debated within their fields of origin by the time art starts to process them.

Nevertheless, it’s a worthy exercise to at least try to keep track. Here are six terms that capture some of the year’s themes that are either having a moment or are about to boil over.

Portrait of Shahidul Alam. Photo courtesy Gideon Mendel.

It would be foolhardy to pretend like there is any upside to the extraordinary persecution of Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam by authorities in his home country this year. But his ordeal and the protests and testimony of his peers and supporters certainly did throw light on the value of his artistic and intellectual contributions—so it’s worth seizing the moment for them.

The most notable of his coinages may be “Majority World,” an eminently sensible term to replace “Third World.” The latter bears the ideological stamp of now-ended Cold War debates between the First and Second (i.e. the Capitalist and Communist) camps—but more importantly, it treats the living conditions of the overwhelming majority of people on earth as a literal afterthought.

Still from Fabrizio Terranova’s video Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival (2016). Photo by Kjell Ove Storvik/NNKS.

I thought Donna Haraway’s term “Cthululscene,” from her recent book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, was too weird to catch on. I was wrong. It’s made ripples, from architecture theory to art zines to eco-art tomes like DJ Demos’s recent Against the Anthropocene, which takes Haraway’s coinage seriously. Partly on its strength, Haraway made ArtReview‘s increasingly head-scratching “Power” list (though she was down to 67 from number 3 last year.)

What, you say, is the Chthuluscene? In response to the popularity of the idea of the “Anthropocene,” the age defined by humanity’s impact on the earth, Haraway proposes imaging instead a new age: “a time when humans will try to live in balance and harmony with nature (or what’s left of it) in ‘mixed assemblages.'” Essentially, it is a call to cohabit with nature.

It is amazing how far Haraway has come from the “Cyborg Manifesto” that made her famous and endlessly quoted by artists, returning to something that sounds very much like the Gaia-focused “goddess feminism” that her original idea of “cyborg feminism” had been designed to counteract. Now she sums up her position thusly: “we are all compost, not posthuman.”

(For the record, Haraway’s “Cthululscene” may come from the same root word as H.P. Lovecraft’s ancient tentacled monster, Cthulhu, but she distances herself from Lovecraft’s “patriarchal monster”—though her description is plenty full of tentacles.)

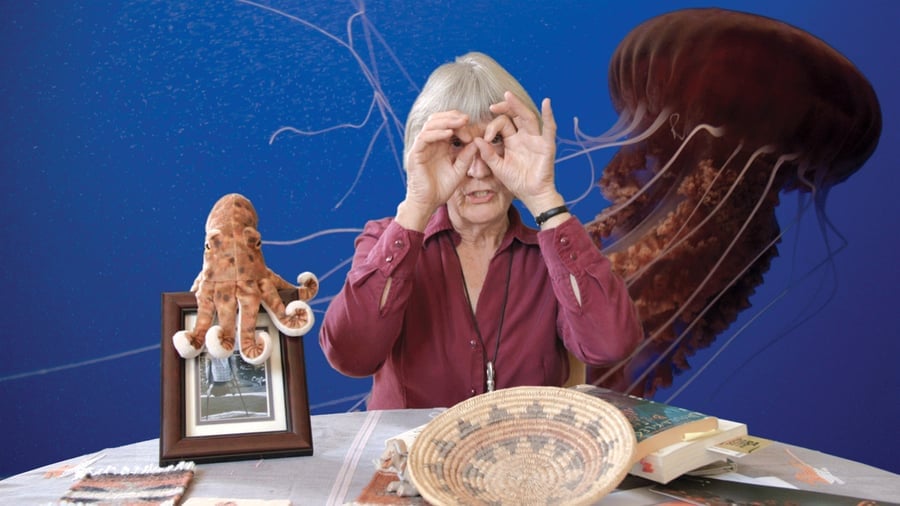

Platform Capitalism (Polity, 2016) and Ours to Hack and to Own (Or, 2016).

Coined by German critic Sascha Lobo, this term has been picking up steam with the publication of Nick Srineck’s recent book Platform Capitalism

For my money, the rise to buzzword status of “platform capitalism” is interesting less as a fully developed theory of some kind of new epoch of capital than of a shift in public understanding of the web. Instead of the internet leveling hierarchies, as it was seen to be not so long ago, most people now feel that it has made them dependent on what are, in effect, new-model monopolies—technological ecosystems that function by dominating some piece of your attention, your social life, your economic aspirations.

“Platform capitalism” has been met by a nascent wave of interest in “platform cooperativism,” as well, popularized by the likes of Trebor Scholz and Tiziana Terranova as a DIY people-powered answer. Whether the latter is a practical alternative or just a propaganda tool for artists and intellectual activists, I don’t know yet. (Scholz’s Platform Cooperativism Consortium at the New School received a $1 million grant from Google’s charitable arm this year).

Tal Issac Hadad, Recital Para um massagista being performed at the Bienal de São Paulo. Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

I have guessed that “attention” is going to become more and more central to how we talk and think about art—because art, as a specific field, must make a case for itself both within and against a lot of other, very pervasive technologies of attention capture. Reframing art’s slowness as a virtue is an obvious move. (I mean, even Childish Gambino is getting in on the “slow art” trend with an installation in New Zealand).

And indeed, curator Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro’s 33rd Sao Paulo Bienal did just this, turning its show guide over to teaching “practices of attention,” and offering a symposium of the same name, organized by curator and writer Stefanie Hessler and scholar D. Graham Burnett, exploring ideas of deliberate aesthetic perception as a way to “reaffirm the power of art as a unique place to focus attention in, to, and for the world.”

Fred Moten attends 2014 National Book Awards on November 19, 2014 in New York City. Photo by Robin Marchant/Getty Images.

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study was published five years ago. In 2018, Moten in particular ascended to something like master thinker status—a strange place to be, given the elusive nature of his thought. The “undercommons” was presented as the inspiration for both the New Museum Triennial and the Creative Time Summit in Florida. Moten was profiled in the New Yorker, and on stage in dialogue at Frieze New York.

As often happens when art gets a hold of an idea, in the process some of the grit was sanded off of it, and the “undercommons” now seems to be used as an affirmation of the marginal.

So it’s worth remembering the tortured, bleak, and contradictory nature of the idea: The Undercommons‘s most famous essay is a guide to how to cope within the dysfunctions of contemporary academia, advocating that the only honest path is claiming a sort of sideways, quasi-anarchistic underground space within and at odds with its failing structures.

“It cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment,” Moten and Harney write in their most cited passage. “In the face of these conditions one can only sneak into the university and steal what one can.”

KCHO’s Para Olvidar (1995) in the 2018 Gwangju Biennale. Photo: Hili Perlson.

To be fair, this is not a real term, and more just my term for a trend I have noticed. Not so long ago, so-called “object oriented ontology” was all the rage, and every biennial or high-profile exhibition was taking about “vibrant matter” and how rocks and plants were people too. This year, pretty much every international art event sang a different tune, and it was by MIA: “Borders—what’s up with that?”

“Questioning borders” was the curatorial leitmotif of the year—and not just at the Gwangju Biennial, whose literal theme this year was “Imagined Borders.” You see it just as much in Manifesta’s use of the metaphor of the “Planetary Garden” as a tool “to aggregate difference and to compose life out of movement and migration.”

Given how central anti-migrant politics are to the world right now, that’s understandable. But given the alarming advances made by nativism, you also start to think that advocating some more specific policy or practice might be needed to put some meat on the bones of the high-flown cliche, and avoid the impression that we are just really congratulating our own broad-mindedness as a globe-trotting audience.