Art & Tech

4 Ways A.I. Impacted the Art Industry in 2024

Here is a handy summary of A.I.'s four biggest impacts on the art world in 2024.

Here is a handy summary of A.I.'s four biggest impacts on the art world in 2024.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The conversation around A.I. in the art world was louder than ever this year as the new technology continued to make leaps forward. It is the subject of a new book A.I. and the Art Market, written by me and published by Lund Humphries, which comes out in the U.S. on February 13.

Some developments in A.I. have taken the world by storm, sweeping the art world up in their winds of change, while others are still slowly emerging, needing more time to achieve widespread adoption. Either way, A.I. always seems to come with plenty of heated debates and controversies.

So what were the biggest developments in A.I. for the art world in 2024? Let’s recap.

A.I. Text-to-Video Generation

A Sora-generated image. Prompt: “Several giant wooly mammoths treading through a snowy meadow, their long wooly fur lightly blows in the wind as they walk, snow-covered trees and dramatic snow-capped mountains in the distance, mid-afternoon light with wispy clouds and a sun high in the distance creates a warm glow, the low camera view is stunning capturing the large furry mammal with beautiful photography, depth of field.” Image screenshot taken with permission from OpenAI.

Since they were first made available for public use in 2022, generative A.I. tools like OpenAI’s DALL-E and Midjourney have exploded in popularity and even the proudest luddites can hardly say they’ve resisted the temptation to try out a few shortcuts on ChatGPT. Google, what? That’s so last century.

We all knew it was coming, but the tease in February of OpenAI’s text-to-video generator Sora, capable of creating animated, photorealistic worlds, still sent waves of excitement around the internet. This month, the company launched public access to the tool, allowing anyone to make silent videos of up to 20 seconds in length from just a short written prompt.

Some people had already had an illicit sneak preview in November, however, when a group of digital artists who had been granted early access to test Sora leaked the tool along with a blistering open letter addressed to our “corporate A.I. overlords.” It went on to criticize OpenAI’s use of artists to “art wash” its image by presenting the tool as helpful to artists, rather than exploitative of their work.

“We are sharing this to the world in the hopes that OpenAI becomes more open, more artist friendly and supports the arts beyond P.R. stunts,” the artists said, urging people to use open-source software instead of proprietary platforms like those of OpenAI.

The Law On A.I.

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst at “The Call” exhibition at Serpentine North Gallery. Photo: Matthew Chattle/ Future Publishing via Getty Images.

That a tool like Sora should struggle to win the favor of artists is little surprise when we consider the huge backlash against the way generative A.I. tools have allegedly been trained by Big Tech companies on a vast bounty of copyrighted data hoovered up from the internet. When you consider that many of the creatives who originally produced this data have received no compensation and are also worried that the cheap, speedy A.I. tools may one day replace them, it’s not hard to see why resentment is simmering. Artists have tried to reassert some agency over their intellectual property, either through the courts or via more guerrilla methods.

In 2024, we have seen some breakthroughs in establishing updated laws that should be much better equipped to deal with disputes over the sourcing of data to train A.I. than the current intellectual property laws, which were written several decades ago and have left both artists and A.I. developers in a state of uncertainty. As part of this process, each region must make a call on how to balance the interests of Big Tech and the interests of their culture sector, and governments will no doubt be under considerable pressure from both sides.

In the U.K., for example, the government just announced plans to draft new protections to safeguard artists from having generative A.I. tools mimic their unique styles or likenesses, a measure being considered as a “right to personality.” In the E.U., meanwhile, the new Artificial Intelligence Act became law in August, which has also landed in favor of prioritizing artists’ rights. For now, we must wait to see which stance Trump’s incoming administration will take on the matter…

Meanwhile, artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst have made some progress in their campaign to have us reconsider generative A.I. as an inevitable but, equally, exciting new model for consensually sharing our intellectual property. They piloted some of these ideas in a critically acclaimed exhibition, which opened this fall at the Serpentine in London.

“It makes more sense to conceive of a model as a collective accomplishment that could distribute collective bounties or collective profits,” Dryhurst said at the show’s opening in October. “That’s very native to this technology. It’s only because we are dealing with old [I.P.] law that we’re running into these issues.”

A Market For A.I. Art?

Ai-Da, A.I. God (2024). Photo: courtesy Sotheby’s.

A.I. may be a pretty hot topic in the art world these days, but that doesn’t always translate directly into sales of so-called A.I. art, a rather amorphous term that could describe an image generated from a prompt on DALL-E or a sophisticated, carefully considered work by a well-established artist who makes use of A.I. along with other mediums. To avoid repeating the hype of the NFT bubble, and amid a wider market downturn, it is no bad thing that a market for A.I. art appears to be developing slowly over a longer period. Encouragingly, 2024 certainly saw some growing interest from collectors in this more challenging category.

In one case, works by artist Roope Rainisto were showcased at Photo London in May. The Finnish artist’s practice is native to Web3, meaning he came up via selling NFTs, and, although the works at Photo London were also offered at NFTs by curated platform Verse Solos, to have them enter a mainstream art market context like a photography fair was evidence of more widespread acceptance for A.I.-generated art by the traditional art world.

The artist recalled later this year how it felt “meaningful to go there physically and talk with exhibition visitors and see their positive reactions to the art. Debate online is often super polarized and doesn’t represent the viewpoints of the average visitor.”

Ai-Da at the United Nations as part of a summit on the positives of A.I. Photo: courtesy Sotheby’s.

Yet the most headline-grabbing instance of A.I. art breaking into the mainstream art world was Sotheby’s sale of a portrait of Alan Turing made by the A.I. robot Ai-Da for more than $1 million. The sale raised some questions about what kinds of A.I. art deserve to be recipients of the mighty marketing efforts of commercial institutions like auction houses and mega-galleries. The Ai-Da project is spearheaded by gallerist Aidan Meller and a group of scientists, with the exact role that the fembot herself played in painting the Turing portrait left somewhat ambiguous.

Meanwhile, many human artists working with robotics and A.I., like Sougwen Chung and Jake Elwes, deserve but have yet to receive the same kind of platform. One can hope that in 2025, we will see more equity of opportunity in the market.

A.I. For Authentication

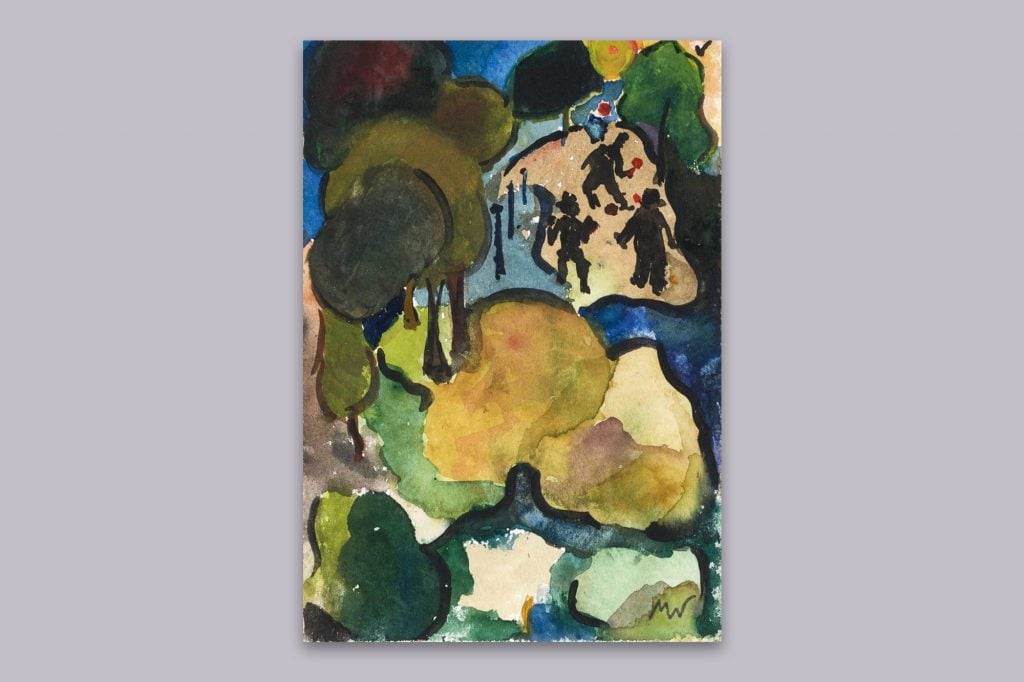

Untitled watercolor by Marianne von Werefkin. Image courtesy Germann Auctions.

The idea of using A.I. to authenticate artworks has been controversial for some time, with initial attempts grabbing headlines for all the wrong reasons. In 2023, for example, we saw the battle of the A.I.s, in which two different A.I. algorithms came to opposing conclusions about whether the same painting could be a work by the Old Master Raphael. What could this mean in terms of ensuring the accuracy of A.I.? The significant complications that come with building effective A.I. authentication tools are covered in greater detail on a recent episode of The Art Angle podcast and in my book A.I. and the Art Market (Lund Humphries).

Despite these drawbacks, several advocates are building a reasonable case for the use of A.I. for authentication. It certainly has some strengths, including some humans don’t, such as its aptitude for “pattern recognition.” This could help it analyze details on the picture plane that may determine whether one painting is part of a larger group (works by one particular artist, for example) or isn’t (cannot be attributed to that artist).

That’s all well and good, but until big market players as well as legal professionals and insurers are willing to trust A.I. and give its judgments weight, it will have no serious standing in the art world. In 2024, however, Germann Auctions in Zurich became the very first auction house to pilot the use of A.I. authentication to back the sale of three artworks by Louise Bourgeois, Marianne von Werefkin, and Mimmo Paladino.

“This is a groundbreaking moment where A.I. has directly influenced a real market transaction, enabling the sale of a piece [by von Werefkin] that lacked a traditional authenticity certificate from an expert—something that, not long ago, would have rendered it ineligible for auction,” said Carina Popovici, founder of Art Recognition, the Swiss start-up providing the A.I. authentication service. She added that other auction houses have already expressed interest since the sale.