Analysis

The Gray Market: Why documenta 14’s Budget Mess Is More Complicated Than It Seems (and Other Insights)

This week, our columnist takes a comprehensive look at both sides of the quinquennial exhibition’s budget debacle.

This week, our columnist takes a comprehensive look at both sides of the quinquennial exhibition’s budget debacle.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

In this edition, a comprehensive look at the week’s single biggest art-business story: the documenta budget debacle…

For the uninitiated: On Tuesday, local German newspaper HNA published a report accusing documenta 14‘s management of running the hallowed quinquennial exhibition’s parent company nearly €7 million ($8.3 million) into the red. If true, the deficit would affect many people outside the niche realm of contemporary art, since documenta relies in no small part on public funding from both the city of Kassel and the state of Hesse to remain a going concern.

According to HNA’s sources, central to the alleged cost overrun was director Adam Szymczyk’s decision to expand the show beyond its traditional home in Kassel to an equally significant counterpart site in Athens. The paper went on to implicate Annette Kulenkampff, CEO of documenta’s parent company, for failing to rein in Szymczyk’s spending. Documenta advisory-board chair and former Kassel mayor Bertram Hilgen also absorbed some journalistic body blows for “allegedly [allowing] the spending to continue in an effort to protect his legacy at the end of his political term,” per my colleague Henri Neuendorf.

In fact, HNA reported that these financial pressures nearly forced documenta 14 to shut down prior to its planned September 17th closing date. Allegedly, an emergency €3.5 million ($4 million) loan from the city of Kassel and state of Hesse was the only buoy that kept documenta from drowning in the fiscal bloodbath.

Christian Geselle, who succeeded Hilgen as Kassel’s mayor in mid-summer, confirmed in an online statement that some manner of financial lifeline had been extended to “guarantee the liquidity of” documenta’s parent company (for which he also serves as chairman). But he declined to provide details or numbers, leaving even this twist in the story wallowing in the murk.

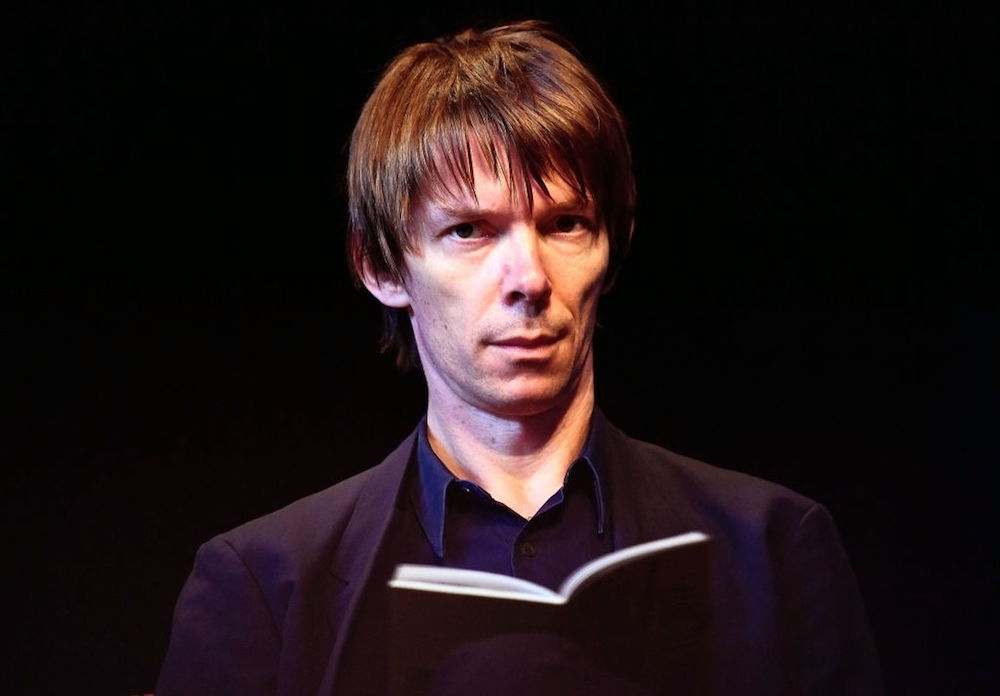

The Artistic Director of the documenta 14, Adam Szymczyk, pictured during the opening press conference at Kongress Palais on June 7, 2017 in Kassel, Germany. Photo by Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images.

Two days after HNA’s report, however, Szymczyk and documenta’s curatorial department counterpunched with an open letter accusing both HNA and local politicians of bending reality like a funhouse mirror. The letter casts its signatories as the victims of a political and media witch hunt fueled by “speculations and half-truths.”

But rather than clearing up the matter, the letter raises even more questions about what the hell happened—not all of them applicable to the exhibition’s critics, either.

From the standpoint of organizational oversight, the open letter’s core claim is that Szymczyk and his colleagues have continually sought and received approval on the exhibition’s budget and dual-city conceit from all “responsible parties” dating back to 2013, before Szymczyk had even been selected as documenta 14’s director. Further, the signatories point out that documenta’s “budget and structural funding has not substantially changed from 2012,” regardless of the current exhibition’s ambitious twin-cities approach.

Nor would any debt owed by documenta’s parent company capture the larger truth of the exhibition’s fiscal impact, according to the letter. Even if ticket sales are indeed slightly depressed in comparison to documenta’s 2012 edition—HNA alleged a dip of three-percent this year—the signatories contend that “the money flowing into the city [of Kassel] through the making of documenta greatly exceeds the amount the city and region spend on the exhibition.”

And even THAT doesn’t fully paint the picture, according to Szymczyk and his colleagues. Because to judge documenta only on its fiscal merits is to miss the point. In their words: “The expectations of ever-increasing success and economic growth not only generate exploitative working conditions but also jeopardize the possibility of the exhibition remaining a site of critical action and artistic experimentation. How can the value production of documenta be measured?”

So, who and what do we trust in this sea of gray?

It’s difficult to say at this stage. An independent audit of documenta 14 won’t arrive until later this coming week, and documenta’s communications department responded to my inquiries by saying that they could “be fully answered by the administration only after the closing of” the exhibition.

This leaves me little choice but to examine the precedents, incentives, and economic rationales that might be animating both sides in this dustup. And after running each one through the same imperfect inquisition, neither documenta nor its antagonists emerges beyond suspicion.

Working backward: Is it possible that documenta really is the target of a politically motivated hit job? Maybe. Politicians have sought favor with the public (or cover from their own errors) by trashing their predecessors for as long as we as a species have been standing upright. And although I’m not well-enough versed in regional and local German politics to offer many specifics, consider these statements from mayor Geselle:

“Documenta is inextricably linked with Kassel… We want Documenta to continue in Kassel as a world-ranking exhibition of contemporary art.”

As Andrew Russeth noted, the 2012 edition of documenta expanded beyond Kassel, but only with “small satellite projects in Kabul, Banff, Cairo, and Alexandria.” Szymczyk, however, took a giant leap forward from that international foothold by effectively exporting half of documenta 14 to a foreign city.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of a local official in Kassel or a regional one in Hesse. The past two iterations of arguably your strongest high-end tourism magnet have established serious momentum toward moving elsewhere—if not entirely, then at least substantially. I don’t think you need to be in the midst of sizing your cranium for a tinfoil hat to wonder if those politicians might be inclined to try slowing or stopping that migration with a little poison press if necessary.

Also potentially relevant is this nugget from Jason Farago‘s review of documenta 14’s Athens program: “The German news media, too, has looked askance at Documenta’s expansion into the capital of what some still offensively call a schuldenland, or debtor country.” This idea gives at least some credence to the possibility that HNA might have an agenda other than good journalism here, too. I mean, not that global nationalism is surging like a lighting-struck electrical line or anything…

Am I saying the HNA story is definitely a plant or a distortion? No. I’m just saying the incentives and precedents don’t rule it out.

Certain details heighten the plausibility of that scenario at least a bit, too. For instance, HNA claimed that the cost of transporting Rebecca Belmore’s work—a life-size marble camping tent titled Biinjiya’iing Onji (From inside)—to documenta 14 rose into the six figures. But a source inside documenta’s curatorial team told Hyperallergic‘s Benjamin Sutton that “the work’s actual shipping costs were only €6,560 (~$7,800) and were entirely covered by the Canada Council for the Arts.”

Who’s telling the truth on this point, and what does it mean for the HNA story as a whole? I don’t know for sure. But I’ve sourced and/or reviewed enough art-shipping quotes in my gallery years to say that if you’re paying €100,000 or more to get a marble camping tent across the ocean, your organization’s dress code must consist of white face paint, rainbow-colored wigs, and floppy red shoes.

All that said: In this vacuum of facts, the most troubling debris flying around the issue still lands on documenta. As far I can tell, the open letter never directly refutes HNA’s report about either the existence of a budget shortfall or its scale. Instead, Szymczyk defense seems to boil down to, “Well, our budget was approved, so how is this our fault?” Which would be naive at best, and disingenuous at worst.

Why? Because a budget is just a planning document. Budgets are wrong all the time, either because they weren’t fully thought through or because they weren’t adhered to. Agreement is not execution. Suggesting you couldn’t have overspent because you had an approved budget is like suggesting you couldn’t have cheated on your wife because you had a marriage certificate.

Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk with first team members of documenta 14. Photo ©Nils Klinger, courtesy of documenta.

It also seems strange to me that Szymczyk and the curatorial team would pump the idea that documenta brings Kassel and the surrounding region much more revenue than it costs—at least, considering that they do so only two sentences down from arguing that documenta shouldn’t be judged on financial returns at all.

Proposing that we need to “question the value-production regime of mega-exhibitions such as documenta” during a budget scandal strikes me as a classic example of the Don Draper corollary: If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation.

This strategy is even more dubious considering that admission fees are a critical plank in documenta’s fundraising efforts. You can’t really strike a budget deal based in part on ticket sales, then later imply that ticket sales are an inadequate measure of success. That’s as much of a bait and switch as inviting guests over for Thanksgiving dinner, then handing them each a plate with nothing but a Bible because what they REALLY need is nourishment of the soul.

Again, based on the information available, I can’t say for sure what happened with documenta’s budget, or who deserves what percentage of the blame. What I can say is that there’s more going on here than meets the eye—on both sides. And that makes me all the more eager to see what comes to light in the coming weeks.

That’s all for this edition. Til next time, remember: Documentary evidence isn’t always definitive truth.