Art World

Here Are the 15 Absolute Best Artworks We Saw Around the World in 2017

From Anne Imhof's remarkable pavilion in Venice to Chris Burden's delightful dirigible in Basel, here's the art we'll remember most.

From Anne Imhof's remarkable pavilion in Venice to Chris Burden's delightful dirigible in Basel, here's the art we'll remember most.

Artnet News

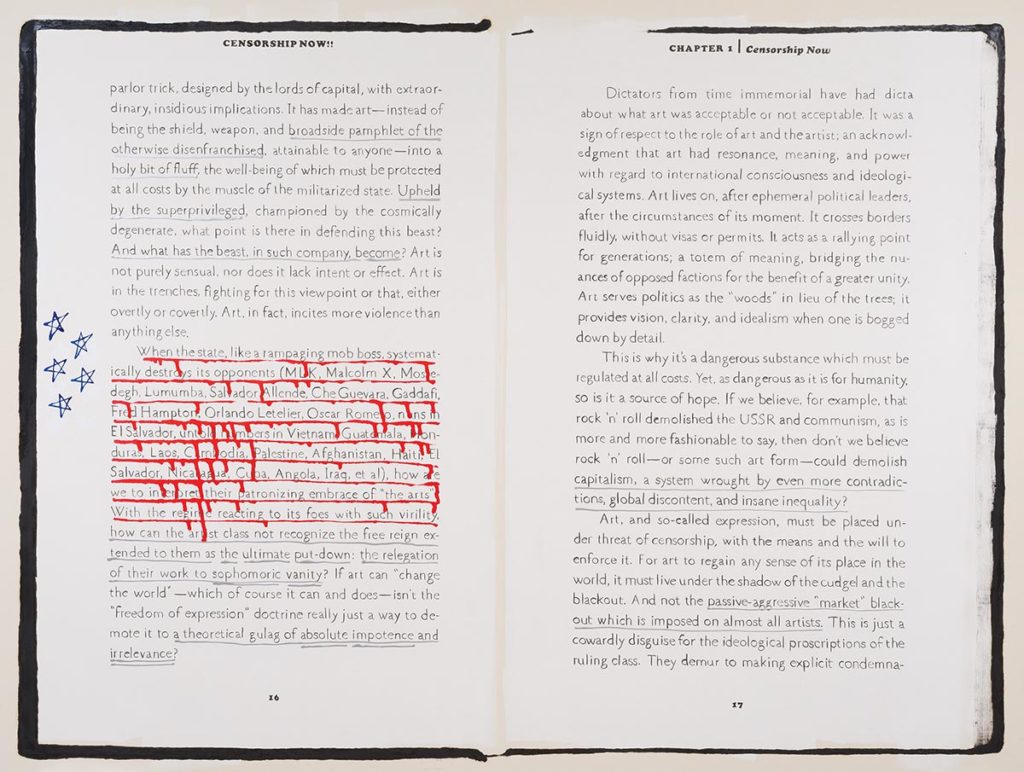

Frances Stark’s Censorship Now (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

Following Trump’s election, everyone pretty much knew 2017 was going to be an angry year, but what remains stunning is how much of that anger turned inward, setting off rounds of extreme vetting and denunciation within the ranks of the left-leaning cultural community itself. It is to the accidental but nonetheless great credit of the Whitney Biennial, the best -ennial I saw all year, that it encapsulated this tendency in an almost uncanny way with the inclusion of two works. The first, of course, was Dana Schutz’s painting of the remains of Emmett Till, which sparked a blazing controversy over whether the white Schutz had the right to portray the grievous power of Till’s black body, and whether the work should be removed from the show (as the curators refused to do) or even destroyed.

The other work, Frances Stark’s cycle of paintings representing Ian F. Svenonious’s screed Censorship Now!, advanced a certain counterargument in the form of a full-throated—if “Swiftian”—endorsement of a campaign of populist, anti-capitalist censorship of the arts, entertainment, politics, and technology. On its face, the argument has a lot of appeal! A good portion of “music on the radio” can be said to “promote class war and celebrate idiocy, sociopathy, immoral wealth accumulation, discrimination, and stultifying social roles”; many video games might well be “designed to cause violent, masturbatory passivity and to create absolutely obedient death machines”; too much culture could be seen as “the thrown voice of Wall Street,” guided by the totalitarian hand of the market.

The paintings faithfully echo Svenonious’s extremist solution: “We need a guerrilla censorship that uses all the cruel tools of a revolution. Pain, terror, absolute mercilessness…. Censorship, termination, eradication, and liquidation. Censorship until reeducation!” A well-intentioned desire for censorship, of course, was behind the calls to remove Schutz’s portrait, to destroy Sam Durant’s gallows sculpture (for a similar charge of cultural appropriation), and to take down the Met’s Balthus painting.

One reason so many people find solace in art is that it celebrates the non-binary, the unorthodox, and the alternative—the umbrageous places where truth and fiction, right and wrong, blend in a way that is recognizably true to life. But what if its all-encompassing embrace is a kind of orthodoxy, and censorship—or other forms of reactive conservatism—is a suppressed alternative? This question, implacable yet pressing (and not going away anytime soon), is the electricity that runs through Stark’s paintings cycle, making it the best work I saw this year.

—Andrew Goldstein

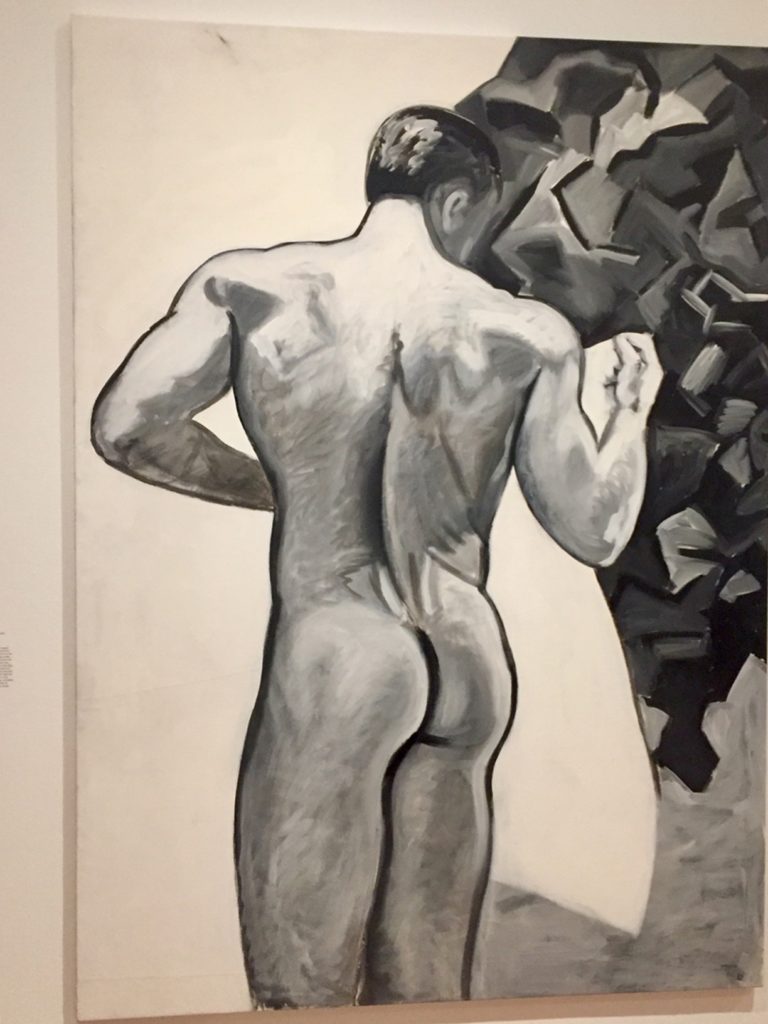

Mundo Meza’s Untitled (Male nude) (c. 1983). Photo: Ben Davis.

Pacific Standard Time offered a couple of shows that, for me, do what I think museums can do at their scholarly best: give you history that expands your idea of what art can do in the present. “Radical Women” told the story of art-as-survival-strategy and personal redemption in a more sweeping way; “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A” was in its way less flashy but more rooted in uncovering a specific time and place. Teddy Sandoval, an artist who created his own great signature brand of painting centering on faceless male figures with prominent mustaches, is one great discovery from that show. Mundo Meza, a nearly forgotten painter whose name gave the show its title, is the other, with his black-and-white paintings standing out as magically both huge and intimate.

—Ben Davis

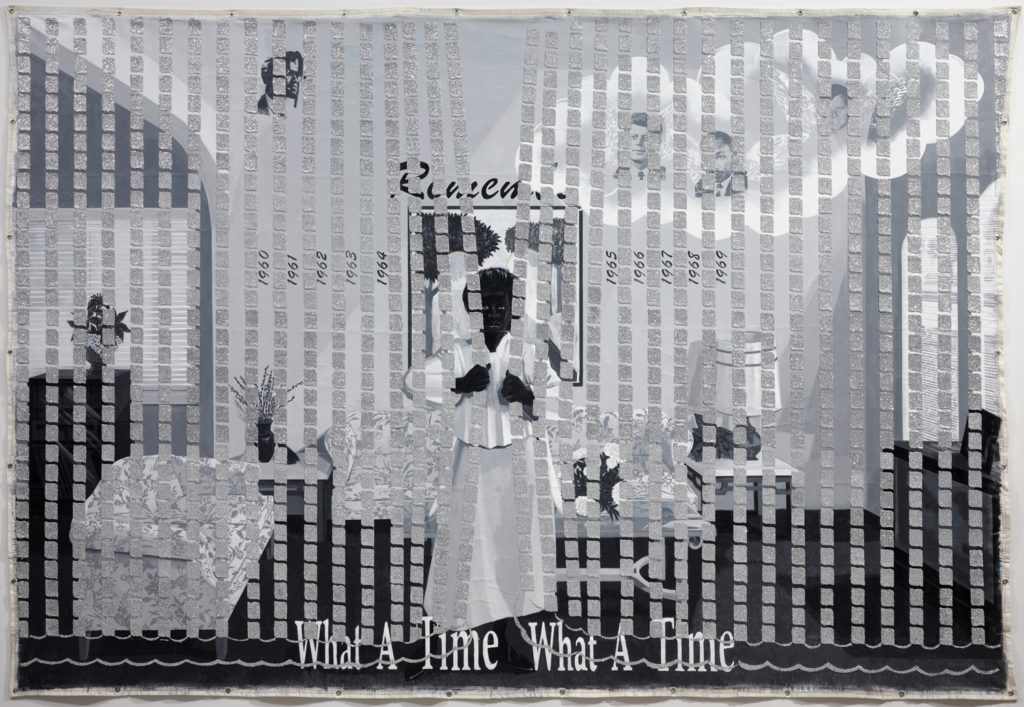

Kerry James Marshall’s Memento #5, (2003). Photo: Jamison Miller, courtesy of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, © Kerry James Marshall.

Carlos Garaicoa’s Abismo (2017). Photo: Renato Ghiazza, courtesy of Fondazione Merz.

J.M.W. Turner’s Cologne: The Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening (exhibited 1826). The Frick Collection, New York; photo: Michael Bodycomb.

Chris Burden’s Ode to Santos Dumont (2015). © Chris Burden, photo by J. Searles.

Emeka Ogboh’s The Way Earthly Things Are Going (2017). Installation view at Athens Conservatoire, documenta 14. Photo: Mathias Völzke.

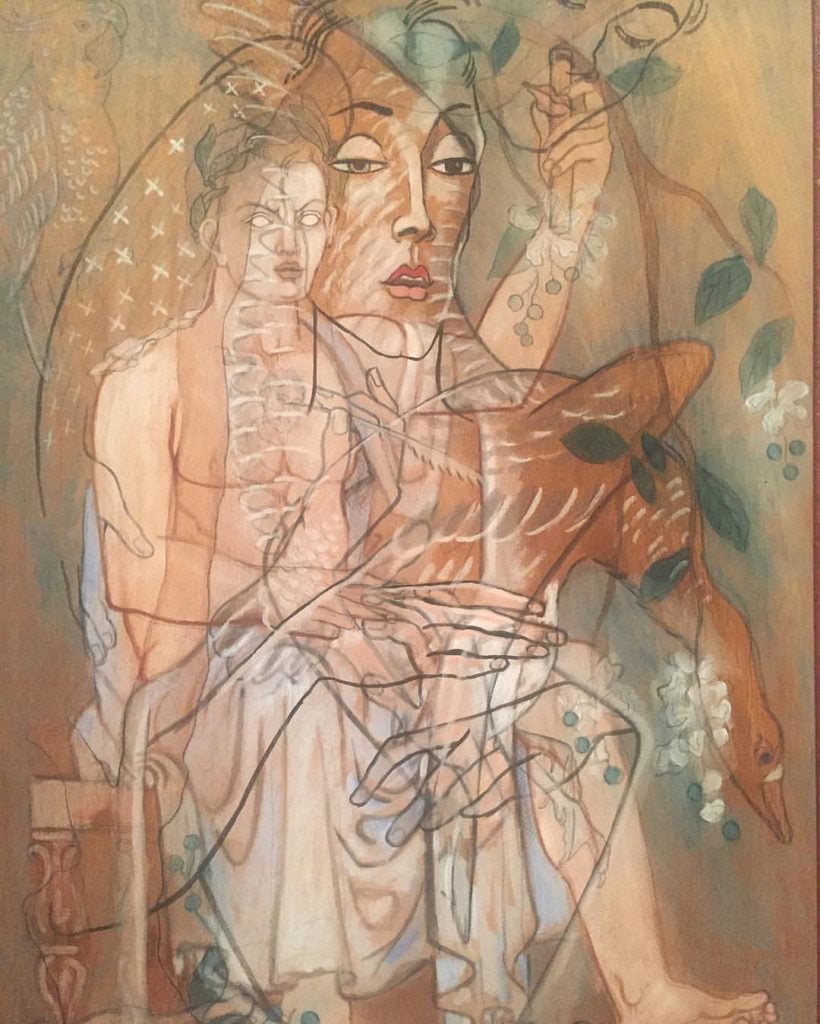

Francis Picabia’s Minos (1929). Collection Gian Enzo Sperone. Courtesy of Sperone Westwater, New York.

Going into “Our Heads Are Round,” I knew shamefully little about Francis Picabia. Every gallery in this survey was a revelation. Early Impressionist-style canvases gave way to Cubist-flavored works, and then the artist’s exploration of Dada; Picabia refused to limit himself to any one style.

The showstopper was the “Transparencies” series (1927–30), in which the artist achieved a multi-layered effect through the use of transparent colored glazes and varnishes, manipulating oil paint to appear almost like the glossy surface of a ceramic bowl. The subject matter, often drawn from mythology, adds to the uncanny sensation that the works are relics from a lost civilization, the image fading to reveal an erased history. Yet Picabia’s masterful composition blends these dueling images into one harmonious whole, so compelling that the viewer longs to continue staring at the dense interplay of line and color.

—Sarah Cascone

Alina Szapocznikow’s Tumours Personified (1971). Photo: © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw.

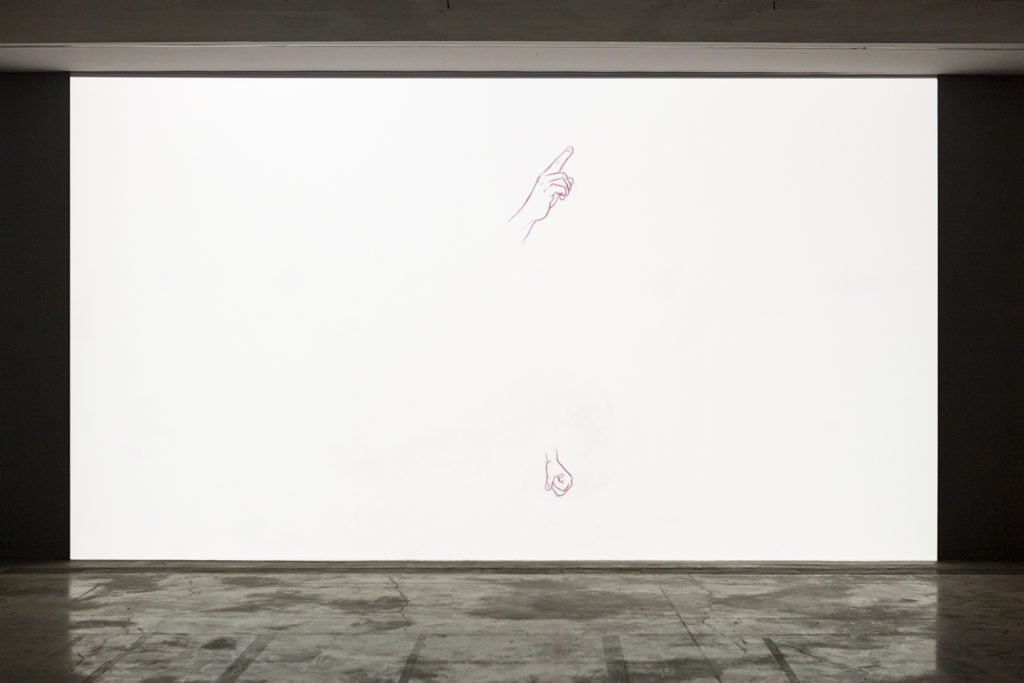

Paul Chan’s Pentasophia (or Le bonheur de vivre dans la catastrophe du monde occidental) (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali.

Strange, haunting, smart, and even funny, Paul Chan’s exhibition “Rhi Anima” stuck with me more than anything else this year.

—Taylor Dafoe

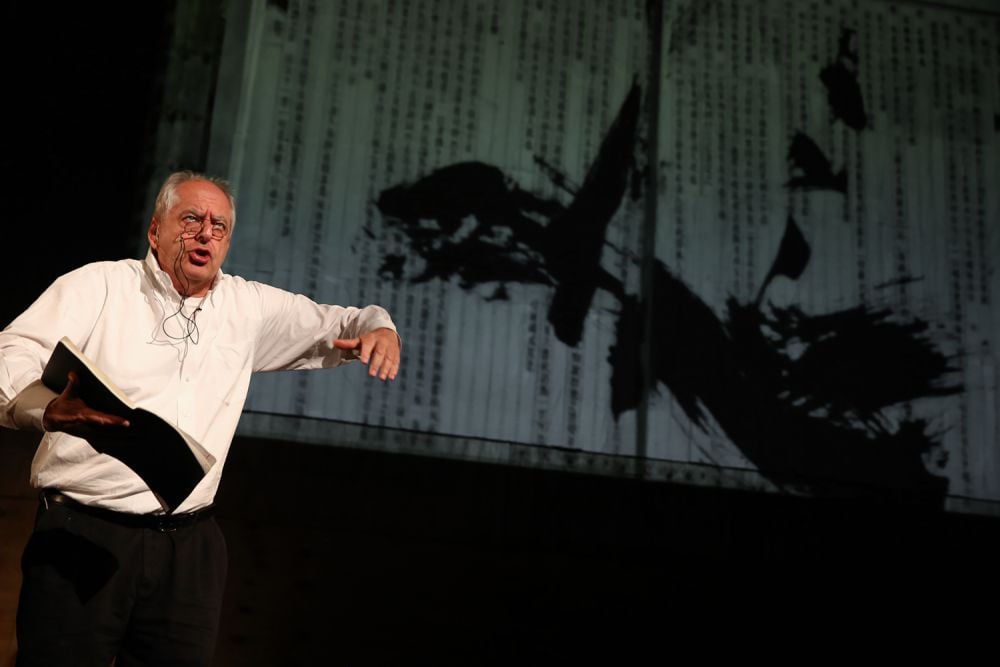

William Kentridge’s Ursonate (2017). A Performa 17 Commission. Photo: © Paula Court.

I was riveted by William Kentridge’s spirited delivery of Kurt Schwitters’s incredible abstract poem Ursonate (1932), part of the Performa biennial in November. In the imposing setting of the Harlem Parish, he performed to a sold-out crowd before a slideshow featuring his trademark stop-motion drawings.

Schwitters’s Dada poem upended the classic form of the sonata by infiltrating it with nonsense—the sonata opens with “Fümms bö wö tää zää Uu, pögiff, kwii Ee.” Kentridge, in turn, inserted the appearance of meaning back into the nonsensical by placing it in a new format—he delivered the gobbledygook with all the rhythms and intonations of a lecture, occasionally emerging from behind his lectern to deliver a point with added zest. Just when you thought it couldn’t get any better, he was joined by a soprano along with a French horn and percussionist (Ariadne Greif, Michael Atkinson, and Shane Shanahan), who sent the proceedings into pure ecstasy.

—Brian Boucher

Billy Bultheel and Franziska Aigner in Anne Imhof’s Faust (2017) at the German Pavilion of the 57th Venice Biennale. Photo © Nadine Fraczkowski, courtesy of the German Pavilion and the artist.

I visited the Venice Biennale with my mom, the same woman who told me I had “a lot of explaining to do” after we toured the 2014 Whitney Biennial. I figured Faust—Anne Imhof’s Golden Lion-winning German Pavilion—would be a similarly uphill battle. First, you have to wait in line. Once you get in, it’s hard to tell what’s going on. A small handful of performers inhabit a sterile, spare series of rooms. Slowly and silently, the performers begin to interact: first staring at each other from across the room, then embracing and grappling with one another on the floor.

As the drama unfolded, my mom and I were equally transfixed. After nearly an hour, neither of us wanted to leave. I kept thinking about what Marina Abramović has said about how difficult it is to teach people to become performance artists, because charisma can’t be taught. Without performing herself, however, Imhof managed to choreograph dancers whose every move demanded our attention. She created an environment in which the rules that normally govern human interaction were suspended. After we left, my mom and I both took an enormous exhale—neither of us realized we’d been holding our breath.

—Julia Halperin

Martin Kippenberger Untitled (1992). Photo: courtesy of Skarstedt Gallery, New York.

In the German painter’s “Hand Painted Pictures” show at Skarstedt, Martin Kippenberger turned the medium of classical self-portraiture on its head by depicting himself in an unusually candid, almost grotesque manner, exploring the artist’s preoccupation with self-representation. In Untitled (1992) the artist displays all of his technical acumen, uniting a sketch-like, rough draft style with highly detailed facial elements. Painted during an extended stay in Greece, the work also also features German phrases in Greek lettering.

—Henri Neuendorf

Pierre Huyghe’s After ALife Ahead (2017). Skulptur Projekte. Photo: Ola Rindal.

Exploring Huyghe’s expansive installation inside a disused ice-skating rink at Skulptur Projekte Münster was one of the year’s most absorbing experiences. I carefully navigated the shattered slabs of concrete on the ground, heading straight toward one of the bewildering chimera peacocks, its dual color schemes running through its median due to a DNA mutation, which was clinging to the dirt-covered windows of the decaying building. (The peacocks were later removed after they started showing signs of stress.) I then descended to the vast space walking between mounds of earth towards a sleek black object. Everything about the space was alive: A pillar of dirt turned out to be a beehive, and the black cube was actually an aquarium made of glass that turned translucent as light came in from a contraption in the ceiling, which opened and closed according to the space’s temperature and humidity. In fact, everything about the hall was controlled to produce specific climate conditions that reflected the rate at which human cancer cells—the historically and medically problematic HeLa cells—divide and multiply. The work felt darkly gripping, with nature’s mutations and anomalies giving the illusion of a controlled environment.

—Hili Perlson

Sue Williams, Horizon Line (2017) at 303 Gallery, New York. Photo by Rachel Corbett.

These paintings stand out to me as something memorably beautiful in an ugly year. Williams’s early works dealing with the violent ravages of misogyny have given way in recent years to lyrical narrative abstractions, packed with neon drama and darkly funny details (curtains opening onto a penis, a girl vomiting) that deliver the right dose of hard political reality, engrossing action, and an exquisite understanding of space.

—Rachel Corbett