Artist Vanessa German owns three homes on the same street in Pittsburgh where she once squatted in a place with no running water. She didn’t have to live like that. She chose to.

It recently became clear that reports touting the city’s improving livability didn’t account for the realities of its Black residents. For them, Pittsburgh remains a tough place to live by any metric—health, education, employment. And those experiencing the very worst of the city—according to a report from Pittsburgh’s own gender equity commission—are Black women.

To assume Pittsburgh is alone in this is to assume racism and sexism don’t play out in some form across the United States. Earlier this year, City Lab published a report ranking the least livable cities for Black women. In addition to Pittsburgh, the top five were Cleveland, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Augusta. Such largely Midwest areas once held promise for Black people, only for deindustrialization to usher in unimaginable inequalities—most times, slowly and methodically, peeling away opportunities one by one, in the hopes that no one would notice.

Not surprisingly, the art scenes in these cities are microcosms of how inequity suffocates growth. Even still, Black women work both within and outside these established systems, tapping in and out through burnout and stress, to make their cities more livable places for artists and creatives.

Paying It Forward

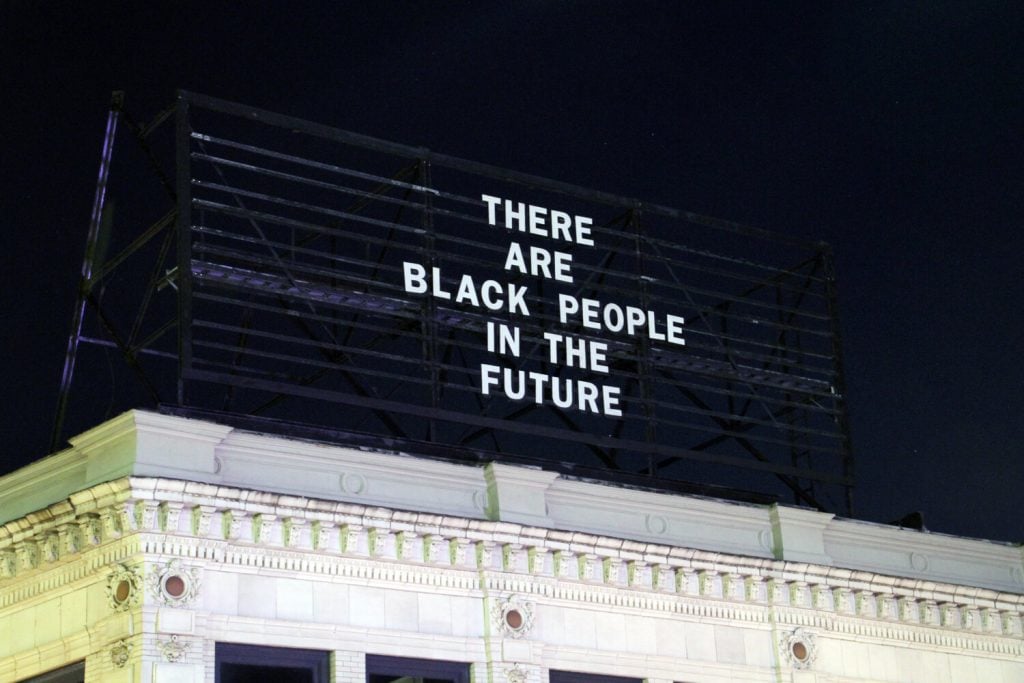

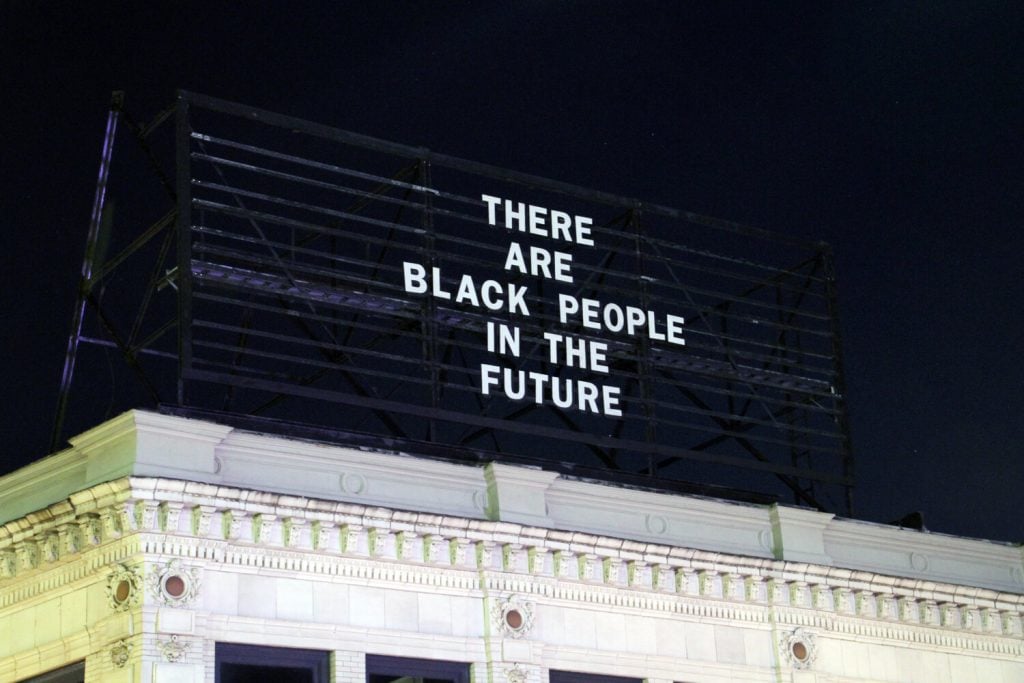

After more than a decade living outside of Pittsburgh, artist Alisha Wormsley returned to her hometown in 2011 to find hastily abandoned communities that were at one time largely Black. She began collaborating with a group of students on a science fiction film. While canvassing for locations and taking in the blighted areas, she thought (despite evidence to the contrary), “There are Black people in our future.” The quote took on a life of its own as an artwork.

“There Are Black People in the Future” by Alisha Wormsley, courtesy of the artist.

In 2018, Wormsley partnered with a local art initiative called the Last Billboard project to display the phrase on a billboard atop a landmark building in a rapidly gentrifying section of Pittsburgh. But after it had been on view for a month, the building’s developers promptly removed it, citing the sign’s supposedly racist and political overtones. (Wormsley noted that previous billboards displayed “quotes about the war in Iran [and] Palestine.”)

“Never once had it been questioned or bothered anybody,” she said. “But you say that Black people actually live in the future, and they take it down.” Unfazed, Wormsley had a group of students incorporate the quote onto stickers, t-shirts, and posters to be displayed all over the city. Vanessa German volunteered to put it on hundreds of yard signs.

Later, Wormsley caught wind of the fact that the president of a major philanthropic organization in Pittsburgh, the Heinz Endowments, had referenced the controversy (and the protests that erupted in its wake) in a discussion of equity at an art conference. “And I was like, [if] he is using this as an example,” she recalled, “then they should support this work.”

She asked the endowment for a grant that would fund emerging artists to use the text in their work in the community. She ended up supporting 11 projects this way.

Similarly, after the CityLab article was published detailing the normalized plight of local Black women, Wormsley decided it was an opportune time to ask for funding for the first-ever residency serving Black mothers. “I’ve demanded the support that I’ve gotten,” she said. “But I know there are other artists of color here who don’t feel as supported as I do.”

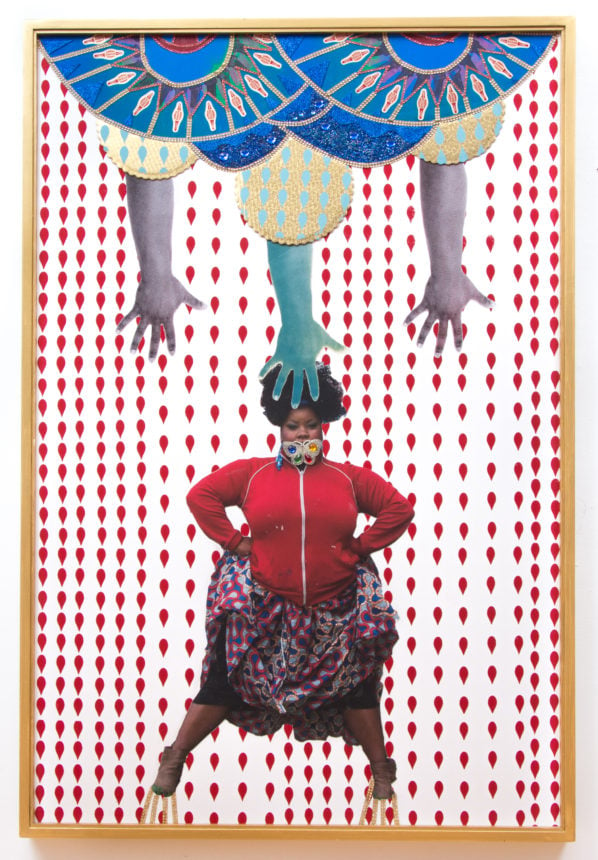

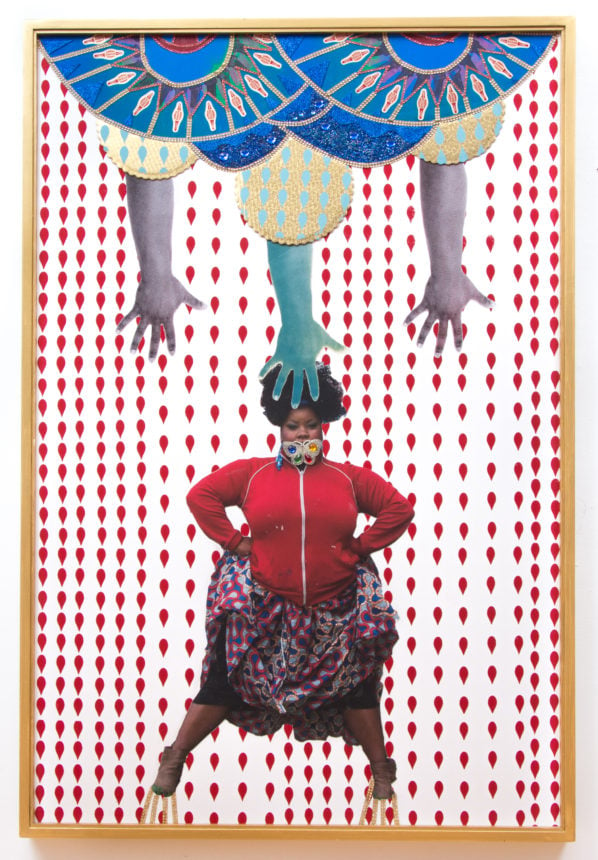

Vanessa German in her exhibition “MATRIX 174/i come to do a violence to the lie” (2016), Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Photo by Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

Working Outside the Philanthropy Box

In her early days as an artist, years ago, Vanessa German attended Harambee Ujima, a storied Black arts festival, and Black Pittsburghers lamented—on her behalf—the lack of options for her as an creator, telling her “what the white world in Pittsburgh would not allow me to do,” she recalled. “And I remember thinking, ‘What makes you think I’m waiting for them for answers?’”

Seeing how much local funders underprivileged Black artists—a disparity documented by Pittsburgh’s own arts council—reinforced the idea that “Black artists and leaders here weren’t held up to the same level as the white artists and the white organizations,” she said. That’s why she decided to “define sustainability” for herself.

“Philanthropy has not investigated its rules for quite some time,” said Celeste Smith, an arts and culture program officer at the Pittsburgh Foundation, noting that large arts organizations are generally awarded more money. The issues raised by both COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter have caused her foundation to take a more honest look at why disparities persist, she said, even among peer organizations where the only difference is that one is Black-led and the other isn’t. But changing the landscape is a slow process.

Funding gaps, along with a lack of institutional support for Black art, has the potential to derail even the most confident of Black artists. When Naomi Chambers decided to pursue a career as an artist after college, not only did most people attempt to steer her away from referencing race in her work, but more than a decade went by before she even saw a show featuring Black art in Pittsburgh—in 2017, when the Carnegie Museum of Art partnered with the Studio Museum of Harlem to organize “20/20.”

“There is this way that Pittsburgh is waking up to Black artists,” German said, “but they’re doing it at a scale that’s still beta, like they’re testing out to see what the Black artists do; when what needs to happen over the next few years is robust investment that acts like a rocket ship—they need to level up.”

Vanessa German, The First Thursday Collage (2016). Courtesy the artist and Concept Art Gallery.

Limitations are not only seen, they’re felt. By choosing to not rely on Pittsburgh’s system of philanthropy, thereby dislodging herself from their ideas of “what a Black artist is and how a Black artist operates,” German lived in her house, with no water, until she found support without any harmful strings attached—through some philanthropy, but mostly by crowdsourcing and bartering. German funded the Art House, a community art space for children in Homewood, in large part by using money from Indiegogo campaigns, work she’d sold, and people who simply wanted to help.

Within that paradigm, what she was doing and making was “adding to the sustainability of [people’s] life,” she said—and vice versa. Like Wormsley, she reinvests the support she’s received into what she’d like to see coming out of Pittsburgh: more space and support for Black creativity.

Black Women Thinking Differently

Its flaws aside, the city of Pittsburgh values art enough to have a council dedicated to sustaining it—which Detroit only formalized last year when, after a push by local artists, the city appointed an arts and culture commissioner (within an municipal agency that, locals worry, is far too under-resourced to make any real impact).

When she arrived in Detroit, in 2008, creative industry builder Cézanne Charles noticed that the model within Detroit’s arts sector was “at its core, to extract value from creators and never return it to those creators.” (Around that time, the local Kresge Foundation created a fellowship for metropolitan Detroit artists, after years without targeted support, but infrastructure remains scarce.)

Charles spent the next 12 years redesigning what Detroit’s creative economy could be. The goal was to help make Detroit’s artists—both emerging and otherwise—feel supported; and for organizations, like the Heidelberg Project, an outdoor art environment the artist Tyree Guyton began building in 1986 to revitalize a decaying Detroit neighborhood, to not feel permanently fledging. Building up Detroit’s ecosystem to support those who are already here, Charles determined, was the best way to achieve economic and social justice in the arts.

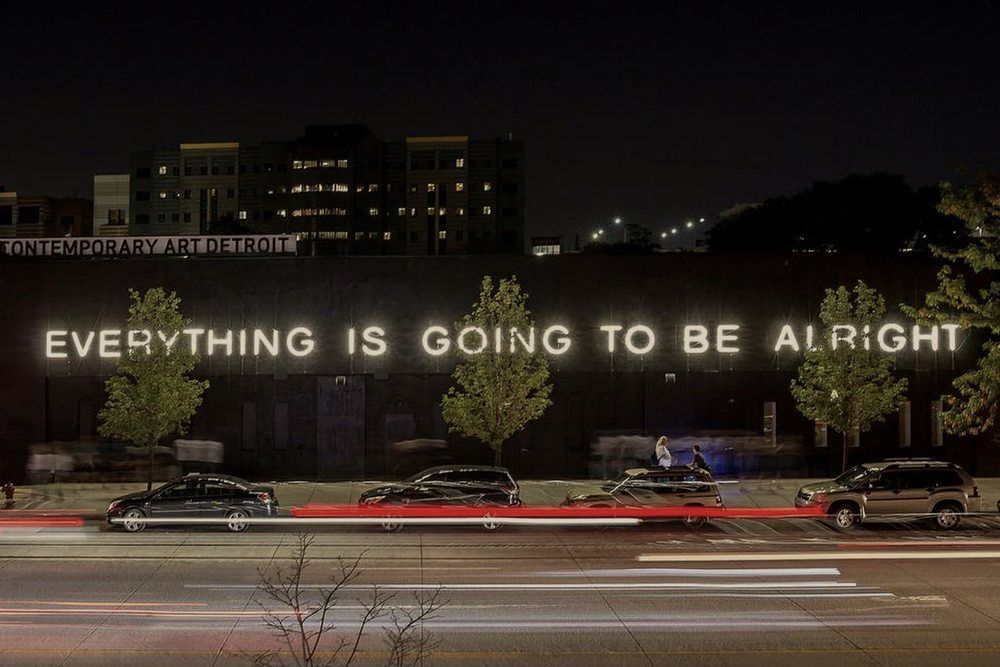

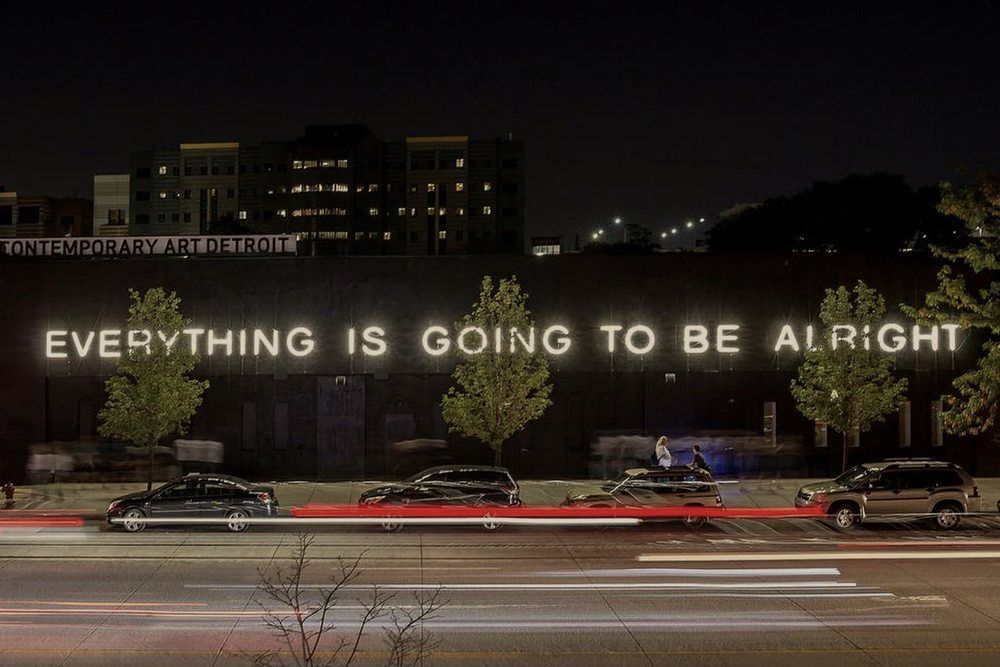

Installation view of a public art project through Shooting Without Bullets. Photo: Rustin McCann.

But social justice is not a blanket term or set of beliefs. It’s site-specific. Operating within Cleveland, a city grappling with Tamir Rice’s death and state-sanctioned violence generally, artist and activist Amanda King, through her organization Shooting Without Bullets, incorporates “social, economic, and political issues happening in Cleveland, specifically,” she explained, in order to create an alternative arts ecosystem supporting Black and brown youth—the next generation of local artists.

That often involves working with existing institutions—negligent structures notwithstanding—to reform the traditional approach to art-world building. She advocated, for example, that the Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland, cancel a planned exhibition of drawings of police killings by Shaun Leonardo—and continued to speak up when she felt that the museum did not accurately portray the story behind the show’s cancellation to the public. King feels as though smaller organizations in Cleveland, however, have been more careful in navigating the intersections of art and social justice.

Advocating for a model that incorporates the needs of Black people can be an uphill battle, particularly in cities with stark inequities and leaders who have little interest in dismantling the system that strengthens them. Charles recalls a common attitude in Detroit: “How do we do hyper-capitalism and shorten the distance between ‘cool-factor’ artists and corporate developers?”

Writer and curator Taylor Aldridge came to Detroit in 2014, when “folks from New York and Los Angeles were coming here,” she said, “and they thought that they could adapt a model that they’d implemented in these larger cities and bring it here to Detroit.”

The facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. Courtesy MoCAD.

Both Aldridge and Charles realized that supporting Detroit meant understanding what Detroit already was, then leveraging what they’d learned. By partnering with major philanthropic organizations, Charles shaped her programs to privilege artists, particularly those of color, who demonstrated a longstanding commitment to their communities—disqualifying interlopers looking to make good on the community without investing in it.

Still, the absence of many on-the-ground advocates, those translating the value and relevance of Black art (to a fickle audience), has had “a cooling effect on the opportunities that artists can get both locally and externally,” Charles said, suggesting that perhaps the city needs more “curators who pay attention to what has been here while also interacting with external art-world forces.”

How Museums Fit In

Aldridge and fellow independent curator Jova Lynne both straddle the line between Detroit’s institutions and its local communities in their work. But acting as the go-between is hard. After a run at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Aldridge chose to leave instead of constantly bumping up against the institution’s conservatism—while also seeing little opportunity for upward mobility. Lynne recently left the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, an institution that she said opened doors for her professionally but left her feeling, very often, “like a token.”

“I’m very connected to the community [in Detroit],” she continued, “and MoCAD has a [bad] reputation locally. And me and my body and my skill sets were being used to create bridges with the community.” (After her departure, a group of current and former staff members issued complaints and a joint letter to the board about the museum’s toxic culture and the role of its director in perpetuating it; the director has been placed on leave and did not respond to a request for comment.)

Samaria Rice and Amanda D. King at a talk at Radcliffe College, April 2019.

In all these cities—Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh—Black curators note that Black work is still relegated to the margins (education or outreach departments) rather than fully integrated into curatorial programs. And while they want to serve as bridges to their communities, they feel that too many institutions are using them to appear like they care about diversity while not actually addressing their racist values.

“Black people can come in, but it’s not like we’re doing anything that makes you feel included in the process,” says Cleveland’s Amanda King. “I equate that to me inviting you to my house, taking you through every room, not giving you a glass of water, not taking your coat, and not saying, ‘Sit down, let’s have a conversation.’”

La Tanya Autry, the only Black employee (a fellow) with curatorial agency at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, said that this situation puts her in a double bind: feeling as if she must shoulder all the diversity work in the institution while also feeling pressured by the local community of Black artists—who consider her the only pipeline to the museum—for opportunities.

What Kind of Art City Do You Want to Be?

With roadblocks like these, how do these cities “say to the world what it wants to say about its art,” Charles asked, “rather than become a pathology in somebody else’s biennial or somebody else’s artwork or somebody else’s [fill in the blank]…”?

As the push to promote Detroit as a nationally recognized city for art continues, Charles hopes to see artists positioned as the city’s most valuable asset and is encouraged to see Black women like Aleiya Lindsay, who cofounded Detroit Art Week two years ago, spearheading the effort. Still, she wonders, “what does Detroit really want to be and what does it have the capacity to do?”

Founders of Detroit Art Week Aleiya Lindsey and Amani Olu. Photo: Jay Adams.

Last year, the organization where Charles worked, Creative Many, shut down all of her programs. Had the initiatives remained intact, they could have provided, she said, “catalytic support for artists and a voice for [them] in their recovery and relief efforts, both in Detroit and at a statewide level” amid the COVID-19 outbreak. While some of her programs have been picked up by other agencies, and a new organization, United Artists of Detroit, was recently founded by Jenenne Whitfield to support local artists, Charles expects the current crisis only to elevate the challenge of appropriately resourcing these endeavors.

In the end, all these Black women behave as “threats to the status quo,” as King says of herself. They are working to establish a bottom-up, mutually-supportive art ecosystem, sometimes reaching out nationally to gain enough legitimacy to do it, so that, as German says of Pittsburgh, “art doesn’t function at that level of the institution or organization [but rather] at the level of the sidewalk.”

If thinking creatively—while navigating an art world which, as it stands, undermines Black people—is what it takes to create a system that doesn’t prioritize the already-prioritized, having Black women at the helm of that initiative may not be a silver bullet. But it is certainly a good start.