Art World

A Developer Censored a ‘Divisive’ Art Billboard Saying ‘There Are Black People in the Future’—Then the Backlash Began

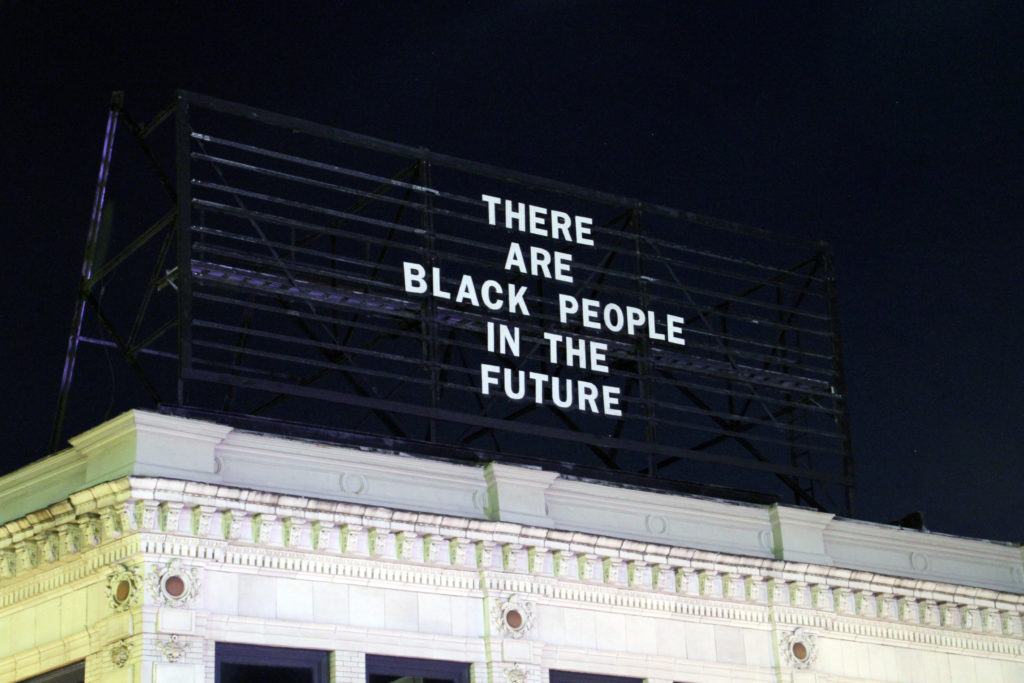

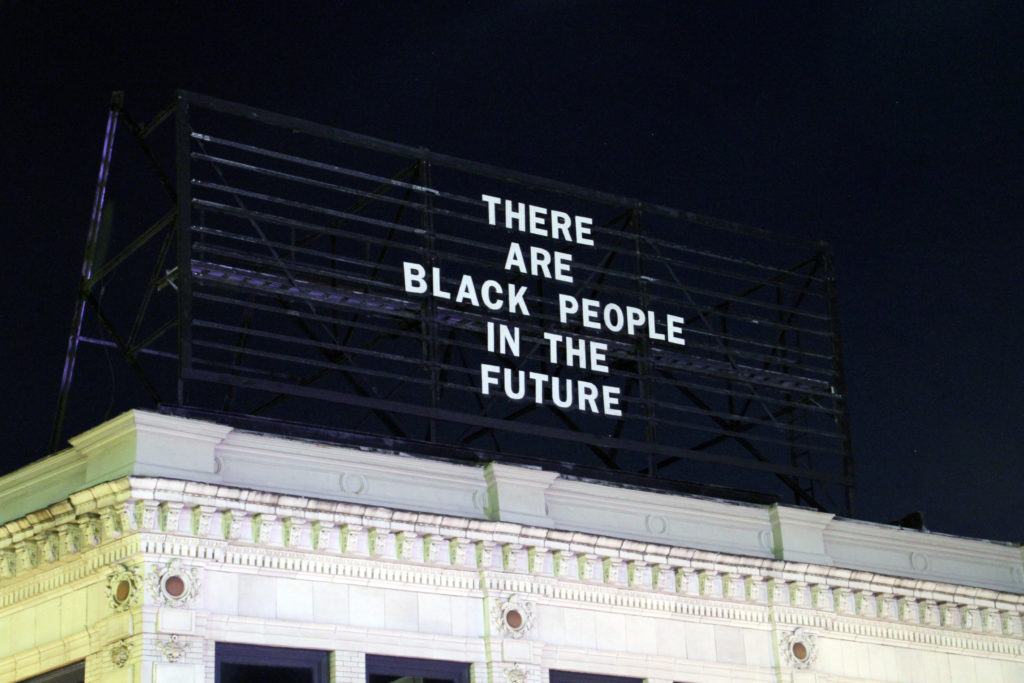

The billboard designed by artist Alisha Wormsley was removed and then reinstated after fierce backlash from locals.

The billboard designed by artist Alisha Wormsley was removed and then reinstated after fierce backlash from locals.

Julia Halperin

For the past five years, a local organization has invited a diverse roster of artists to compose simple messages on a billboard in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Many of the previous participants—including Laure Prouvost, Paul Ramírez Jonas, and Pablo Helguera—are known to confront challenging subjects, ranging from politics to discrimination, in their work. But the content of the billboards never caused any controversy—that is, until now.

The contribution of the Pittsburgh-based artist Alisha Wormsley, whose text reads “There are Black People in the Future,” set off a firestorm in the East Liberty neighborhood and online.

The trouble began last week, when the landlord of the building asked the project’s organizers to remove the work, which had been on view there for the previous month. After news of the work’s removal began to spread, however, scores of supporters voiced their opposition to the decision—and the landlord had a change of heart. This morning, Eve Picker of We Do Property Management announced that Wormsley’s work could be reinstated immediately.

Picker told artnet News in a statement that her original request came after she received complaints from “a number of people in the local community who said that they found the message offensive and divisive.”

Alisha Wormsley’s contribution to The Last Billboard project in Pittsburgh. Photo courtesy of The Last Billboard project.

But she may not have been prepared for the backlash to the backlash. This morning in a separate statement, she said that in the previous 24 hours, the company had “received a number of emails from people who said they are not offended by the sign and are saddened by its removal. They far outnumber the people who originally approached us about being offended.”

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Picker was more candid in a message to Jon Rubin, the founder and curator of The Last Billboard project. She told him that her inbox had been flooded with messages accusing her of being a racist. “So here we are,” she wrote to him, according to the newspaper. “Art has caused friction. Perhaps that’s what you wanted but it shouldn’t be aimed at me.”

Indeed, opposition to the work’s removal mounted after Rubin posted a statement online about the billboard’s removal on April 3. He noted that Wormsley’s text is a natural outgrowth of her work, which is inspired in part by Afrofuturism. “I believe in the power, poetry, and relevance of Alisha’s text and see absolutely no reason it should have been taken down,” Rubin said.

He added: “I find it tragically ironic, given East Liberty’s history and recent gentrification, that a text by an African American artist affirming a place in the future for black people is seen as unacceptable in the present.” He declined to comment further when reached by artnet News.

Picker, the landlord, maintains she was within her rights to ask for the Wormsley’s message to be removed because the lease agreement states that the billboard cannot present messages “that are distasteful, offensive, erotic, [or] political.” She acknowledged that Rubin had erected works in the past without seeking formal approval, but said that in the future, the Last Billboard project must follow the formal process outlined in the lease agreement.

Ironically, Wormsley has been celebrated specifically for her work with public art in the past. In 2015, she accepted the Pittsburgh mayor’s award for public art for her involvement with the Homewood Artist Residency, a program that brings artists to the city’s Homewood neighborhood to create a project inspired by the community.

In a statement posted on her website today, Wormsley said she was “deeply saddened” by the work’s removal but “comforted by how my Pittsburgh has stood up.”

She added: “I think we all know what it is to have discomfort. Let’s begin to work on methods to constructively investigate that discomfort without using power over anyone or anything else.” She also encouraged others to make work out of the phrase. “This text is a sentence I do not own, it is for anyone who wants to use it,” she said. “Please. Take it.”

On April 18, the artist is scheduled to participate in a public panel discussion about the billboard and broader questions about how communities ought to navigate art in public spaces.

Read Wormsley’s full statement here.