Art World

Meet the Brooklyn Artist Who Lent Art-World Cred to Netflix ‘She’s Gotta Have It’ Reboot

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh takes us behind the scenes.

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh takes us behind the scenes.

Hannah Pikaart

In the Netflix reboot of Spike Lee’s film She’s Gotta Have It, Nola Darling (DeWanda Wise) navigates three separate romances; battles gentrification in Fort Greene, Brooklyn; and comes to her friends’ aid in their various crises, all while trying to further her career as an artist. Unlike in the 1986 original, however, Nola’s art is not mere window-dressing—it’s an essential part of the show.

The real-life painter behind the work used in the series, Brooklyn artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, piqued Lee’s interest after he saw her street art campaign “Stop Telling Women To Smile.” Lee recruited Fazlalizadeh not only to create the portraits for the show, but also to serve as a consultant.

Fazlalizadeh spoke to artnet News by phone about how her own art (both on canvas and in the street) helped bring Nola to life and what it was like to collaborate with the Emmy-winning, Oscar-nominated director.

How did you get involved with the production? Was Spike Lee familiar with your work beforehand, or was there a casting call for artists?

No, there was no casting call. He saw my work in the streets—one of my “Stop Telling Women To Smile” pieces—and found me via Instagram. We started out working on another project, his movie Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. He bought a few of my paintings and put them in the film. After that, he brought me a script for She’s Gotta Have It and told me he wanted me to do all of the artwork for Nola. Soon after that, he told me he wanted her to also do a street art campaign that was similar to mine.

What were your duties for She’s Gotta Have It?

As the art consultant, I was in the writer’s room to give insight, suggestions, and my thoughts on a black woman artist in her late 20s. So I was advising on who some of the character’s favorite artists might be, galleries she might visit, places she may hang out. That phase lasted a couple of months. When Netflix approved the scripts and production started, in October, that’s when I began the actual paintings.

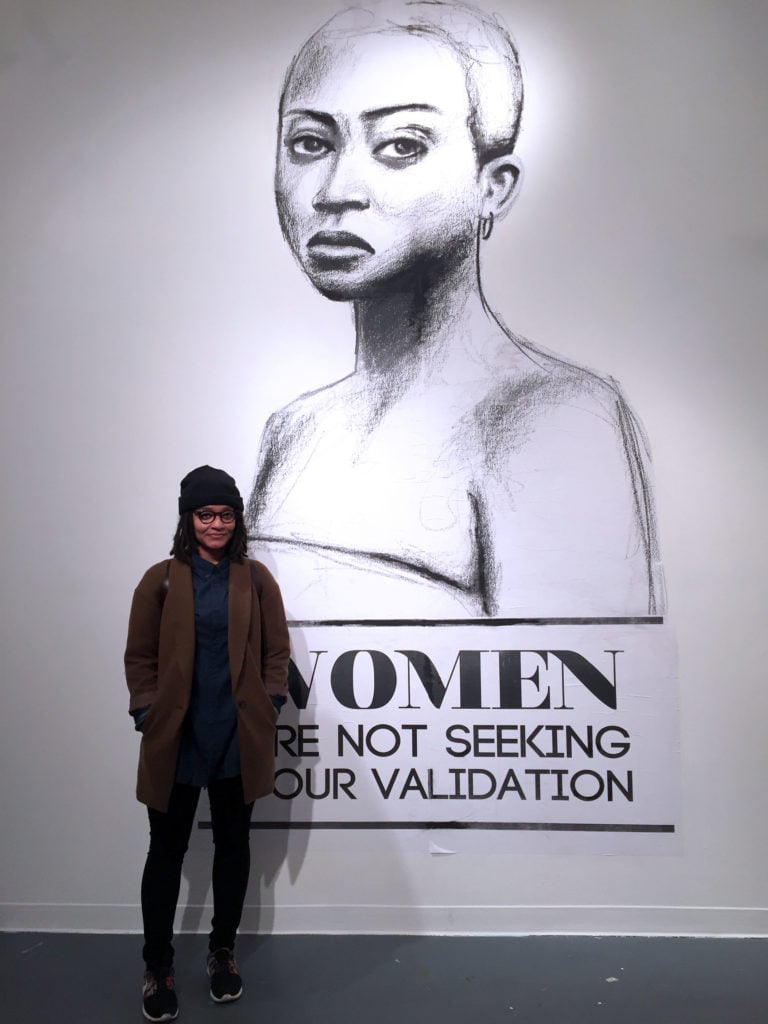

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s street campaign “Stop Telling Women To Smile.” Courtesy of the artist.

In the writer’s room, were there any particular moments and plot points where you guided them in a different direction?

Yeah, I think there was a little bit of that. I would read each script and I would make my notes and say, “I think maybe an artist might actually think this, feel this way, or do this.” Sometimes I would just have conversations with the writers, not talking about anything specific, but about my frustrations and challenges as an artist. And I would see some of that stuff come up in their language or dialogue.

Did you feel like you had to adapt your work to Nola? What was the process of adapting your work for Nola’s character?

Yeah, a lot of the paintings you see in the show in the background of her apartment are paintings of mine from the past two years, so they weren’t done for the show. The paintings Nola creates are the pieces I worked on, like the portrait of Shemekka [whom Nola helps when Shemekka winds up in the hospital after her butt implant explodes after a fall]. Those pieces were written in the script, for that character. So it’s my hand doing the work, but it’s not necessarily my painting. If it was, then I might have done some things differently.

When did your interests as an artist diverge from Nola’s? In one episode, she talks about how she paints the “free black female form.” Are you interested in painting the free black female form, or do your interests lie more with social issues pertaining to women?

Yeah, there’s a big difference between my approach to my work and Nola’s, speaking as if Nola is a real person. I don’t look at myself as painting the free black woman form—I don’t know what that is and I don’t presume to know what that is or to make that. I paint a lot of portraits—I have been a portrait painter for a long time, but a lot of my work is coming from the attempt to reflect the experiences of these people. I think Nola is trying to use these people as a representation of what she thinks they are or who they should be, whereas I paint people as who they are. For example, she paints Shemekka with a curly Afro, when in real life Shemekka has a long weave. If I were to really paint that, I would paint her with the long weave because that is who she is and that’s how she represents herself, and I think that is beautiful enough.

You’ve expressed some concerns about the 1986 film version of She’s Gotta Have It. What made you decide to get involved in the remake?

Back in 2014, when Spike and I had just met, we would talk about my art, his work, and She’s Gotta Have It. I expressed to him my concern about the sexual assault that happens at the end of the movie. Spike told me that he has regretted that, and he said that publicly over the years. Knowing that put me at ease with the movie itself. And then it’s Spike Lee. I admire him—he’s incredible at what he does. It felt like I was being heard and that it was more a collaborative process, which is why I decided to do it.

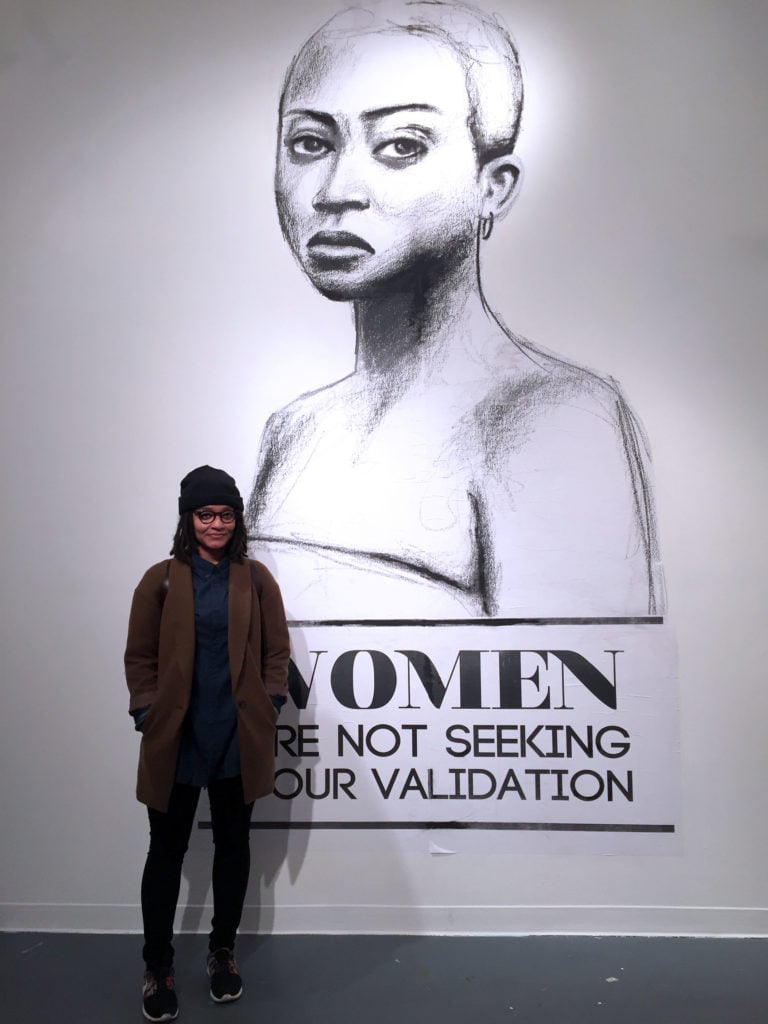

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh installs her street campaign “Stop Telling Women To Smile” with wheat paste. Courtesy of the artist.

Your series “Stop Telling Women To Smile” inspired Nola’s “My Name Isn’t” series. How have your own experiences, both as a black woman in street art and a black woman in the formal art world, informed or inspired your series?

“Stop Telling Women To Smile” was informed by my experiences with street harassment. It’s been a big part of my life for a very long time. And, because I’m black, the street harassment and the sexual harassment that I receive is often overlapped with racism. I began working in public art when I was living in Philadelphia, and I was working as a muralist and it just kind of clicked to me to create art about this experience that I have all the time and to create it in the space where it happens. It’s not something that I can ever remove myself from, so it’s going to find itself in my work. I imagine more of my work will be inspired by those identities because that is how the world perceives me.

Did Spike Lee give you any instructions or parameters?

A little bit for some pieces. He gave me a lot of creative license for the portraits, but there were some that he had a lot of say in and we went back and forth on a few. I told him, “I think Nola would do this. I don’t think Nola would do that.” And he would say, “No, it needs to be this. I want this.” Spike had the final say in a lot of things. I found that to be frustrating at moments, but I am creating these pieces for the show. So for the “My Name Isn’t” campaign, there were some names on there, like “My name isn’t hoochie mama.” I would say, “Spike, nobody actually says that anymore.” But if you actually look at the show and see the street harassment montage that happens early in the first episode, it’s very stylized—it’s very much a caricature. What he’s doing is taking a real-life issue and adding comedy to it, and that can be a very dangerous thing to do. It can either go well or really not well, but I think it’s up to the audience to determine that. So being an artist who works with street harassment, who has a real-life art series about this, who is a painter of women, who feels really close to the character of Nola, I wanted the work to be as realistic as possible, but there were some moments and some things that Spike interjected and said, “This is what we need for the show.”

Do you think the show accurately represents the intellectual life of an artist, or do you think it over-romanticizes that life?

A little bit of both. I felt very close to the character Nola. She’s 27, she’s an artist trying to make it in New York, to be a New York art-world darling. She wants residencies and to be represented by a great gallery, and to sell her work for a lot of money. For her, that’s the way to be an artist. But I think she is starting to realize there are other ways to be successful, and that is not just about others giving you validation. It’s about you validating yourself and feeling good about the work you are making. That was a process that I went through and maybe am still going through. I moved to New York when I was 27 and wanted those same things, and now my goals have changed a little bit. I found some success in a non-traditional way, so I feel close to her in that way, and because of that I relate to a lot of what she is going through, so it is realistic in some ways. We also see her living alone in this apartment that costs a lot of money, we seeing her wearing these really fabulous clothes, we see her living a life that doesn’t seem to match up to the struggle that she is living, so maybe that’s not realistic. But I hope in the seasons to come, if we get more seasons, that we see how that traditional method of breaking into the art world isn’t the only one.