Analysis

The Gray Market: What the ‘Salvator Mundi’ Whodunnit Says About Saudi Soft Power (and Other Insights)

How a $450 million da Vinci and a handful of petrocrats siphoned much of the art-market oxygen out of Art Basel in Miami Beach.

How a $450 million da Vinci and a handful of petrocrats siphoned much of the art-market oxygen out of Art Basel in Miami Beach.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, assessing two battles for attention at the top of the art market…

TWISTS OF FATE: Although Art Basel Miami Beach still soaked up plenty of coverage during its run, the week’s single most dominant conversation piece was the multi-day shell game played out over the identity of a single buyer who made their mark nearly a month earlier.

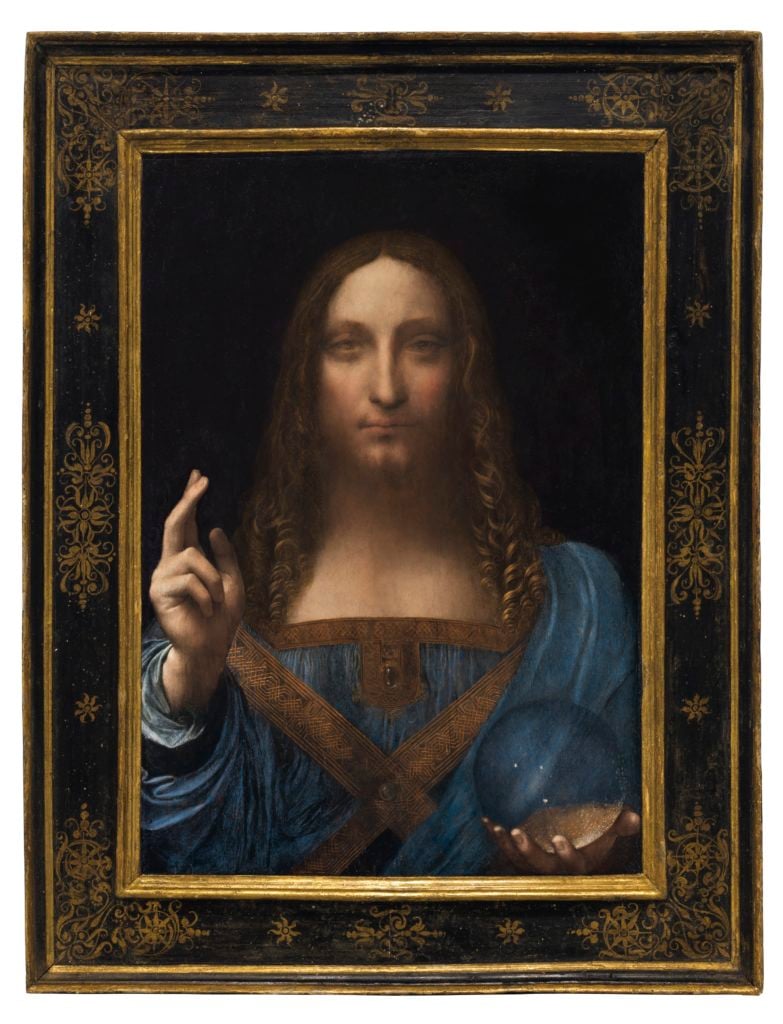

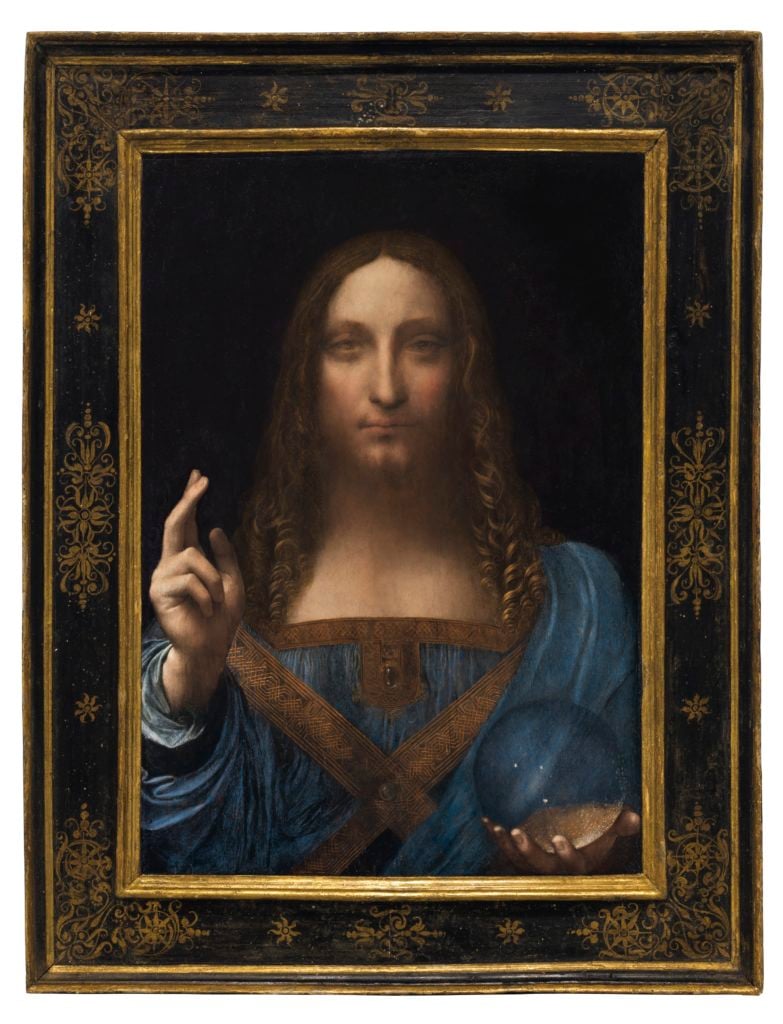

Twenty-one days of speculation finally seemed to end on Wednesday, when The New York Times reported that Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi (ca.1500), the rediscovered masterpiece that sold for a mind-melting $450.3 million at Christie’s November 15th contemporary evening sale, had been acquired by the largely unknown Saudi prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud.

Or so we thought at the time. But on Thursday, the Wall Street Journal leveraged US intelligence reports and anonymous firsthand sources to conclude that the REAL buyer was in fact a much higher-profile relative and associate of Prince Bader: Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

In this version of events, Prince Salman may have asked Prince Bader to act as a proxy, to try to lower any eyebrows raised by such an extravagant purchase taking place in the midst of a Saudi anti-corruption purge spearheaded by none other than Prince Salman himself.

Otherwise, the campaign might look less like a government ethics drive than a consolidation of power—a high-stakes geopolitical version of a strict parent confiscating his kids’ Halloween candy “for health reasons,” only to be found passed out on the couch shortly after under a veritable grenade blast of nougat dust, chocolate stains, and ravaged wrappers.

(Side note: My colleagues at artnet News speculated Prince Salman was the true buyer shortly after the NYT story broke.)

Louvre Abu Dhabi launches with a bang, courtesy of Facebook.

But then the narrative torqued AGAIN on Friday, when Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture & Tourism released a statement claiming ownership of Salvator Mundi. Further, the organization announced that the prized painting would be placed on view at the recently opened Louvre Abu Dhabi at an indeterminate point in the future.

The release clarified an ambiguous tweet posted by the museum’s account on Wednesday, in which the Louvre Abu Dhabi advertised that it would be exhibiting Salvator Mundi, though not by what mechanism (loan versus rental versus ownership).

The Saudi embassy in Washington, DC, also backed up the narrative by asserting that Prince Bader, not Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, had acted as an agent for the Abu Dhabi cultural bureau. Which still doesn’t rule out that MBS was ACTUALLY behind the whole situation anyway, but hey, choose your own adventure.

From there, attention shifted to the possible geopolitical cause and effect of this move, with a special focus on Saudi Arabia’s alliance with Abu Dhabi in an ongoing gulf-region power struggle.

And thus a da Vinci and a handful of petrocrats siphoned much of the art-market oxygen out of Art Basel in Miami Beach from half a world away.

Here’s what I’m fascinated by, though: in the aftermath of the winning bid for Salvator Mundi, many industry observers went to great lengths to credit (or blame) Christie’s unprecedented marketing efforts for their role in goosing the final sales price to such absurd heights. The buyer’s identity then instantly became one of the hottest topics in the art market and, to some extent, the broader public consciousness.

However, no one was able to confirm any solid intelligence on the answer for three solid weeks—until key information in the story miraculously came to light on the day that Art Basel in Miami Beach, the last major event of the 2017 art-world calendar, was set to open to VIPs.

This revelation was then followed by a head-spinning reversal the day after, when the fair planned to welcome more preferred guests during select daylight hours and the public to their opening in the evening.

And this second twist just so happened to be succeeded by a THIRD the next day, which harbored the first full slate of viewing hours for ABMB—and for many, if not most, of the heavy hitters, the last obligations to meet before hustling to the nearest flight out like it was the Fall of Saigon.

Granted, finding patterns and narratives in utter randomness is one of the most enduring hobgoblins of the human brain. (Ironically, I was reminded of as much by this book on my flight to Miami on Thursday.) All of the above could be little more than a series of chance events.

Still, isn’t it at least a little curious that this desperately lusted-after story unfolded step by step over the past three days when everyone in the arts was absolutely required to pay attention to the headlines—not to mention when a huge proportion of us were all sweating together in the same convention centers, bars, and restaurants to try to do as much networking (read: gossiping) as possible?

Might it also be relevant that three weeks ago, so many of us were saying, “Damn, savvy marketing really made a world of difference in the Salvator Mundi saga, huh?” As well as that, as good (or evil) as you may have thought the Christie’s staffers contributing to that publicity coup were BEFORE the sale, they might have also gained the added firepower of PR specialists in two gulf states AFTER it to conceive how and when to reveal the owner in the highest-impact way?

Again, this could all just be a collision of coincidences. But even if it is, I think it would be wise for anyone who believes we entered a new era of art-industry marketing with the Salvator Mundi acquisition to consider the implications of that shift whenever the headlines, and timelines, get this juicy from now on. Because if this attention-getting, news-cycle-dominating info roll-out wasn’t carefully orchestrated on a day-by-day basis, a similar one will be soon.

An art mega-yacht, even a Koonsian one, will get you only so far. Photo: Andrea Ferrari.

PROXY WAR: On Friday in the Financial Times, Jan Dalley used the freshly renewed interest in Salvator Mundi as a cafeteria tray to serve up some of the art market’s most-often-maligned byproducts. Featured were such Gray Market favorites as the phenomenon of art as an (alleged) investment, the inherent game-ability of a uniquely opaque system, and the ever-growing awareness that many of the world’s best (or at least priciest) works are being siloed in private storage facilities rather than exhibited for public consumption. (Full disclosure, a line from my own Salvator Mundi piece for artnet News also makes a cameo.)

The core theme that emerges from Dalley’s analysis is our collective tendency to transmogrify high-end art into other roles. And Salvator Mundi is a perfect example.

Walk back through the unveiling of its new owner, and the painting trades out identities as often as a college freshman only able to get his hands on budget-grade fake IDs. It’s a socioeconomic trophy! It’s a geopolitical pawn! It’s an emblem of obscene wealth disparity! It’s the Maltese Falcon in a modern detective story!

The da Vinci—and, to a lesser degree, many of the premier works on view at Art Basel in Miami Beach this past week—could legitimately become any of these things. It all just depends on the context and the price.

Nevertheless, what makes blue-chip or gilt-edge pieces like these a trigger for widespread fascination and intense scorn is that, underneath all the symbolic mutations, some of them are still legitimately great works of art. And I think many, if not most, people living beneath the apex of the economic pyramid still feel they should be entitled to a relationship with great art.

Consider this: In the NYT‘s original story about Salvator Mundi’s buyer, they referenced the Saudi crown prince’s 2015 “impulse purchase” of a 440-foot yacht for half a billion dollars. But that buy—based on the numbers, an even more extravagant one than the da Vinci—caused no broad public outcry, let alone talk of an existential crisis from within the always-topical confines of the high-end boating market. I doubt that many us even knew it happened before now.

I’d also wager that if some plutocrat paid half $450+ million for—to invoke F. Scott Fitzgerald—a diamond as big as the Ritz, almost no one would talk about the sale as a bastardization of good taste and ethics. In fact, the largest colorless diamond known to man sold at Christie’s the day before Salvator Mundi, albeit for “only” $33.7 million… and almost no one cared. Why not? Because most, if not all, people would probably agree that a diamond’s only job in modern society is to be expensive.

Unlike in art, there is no potential for self-revelation or transcendence in these other objects. It would be seen as ludicrous for the average person to seek out intellectual expansion by making a pilgrimage to see a gargantuan marine luxury craft—sorry, Jeff and Dakis—just as it would be for you or me to strap on a headlamp and dive into a subterranean cave to search for insights about humanity in the surface of Earth’s biggest, sparkliest rock. Both are trophies, but they’re also mental, emotional, and spiritual dead ends to us, even in 2017.

I think this matters. A few years ago, the author of “Cloud Atlas,” David Mitchell, proposed that what separates people in any generation, past or future, is what they take for granted in their lives. Based on the differences in coverage and interest around these multimillion-dollar purchases, evidence suggests that the general public doesn’t expect access to mega-yachts or mega-diamonds.

But the continuing exasperation over Salvator Mundi’s exorbitant sales price—and the struggle over the work’s “true” meaning—suggest something that many of us do still take for granted, even outside the industry: that we deserve access to artistic masterpieces, even if we don’t have the resources to collect them ourselves.

Despite the many, many aspects of the cultural realm that raise legitimate concerns, then, this enduring expectation means that we may not have devolved as much from our ancestors as we often worry. And that’s an encouraging sign for the arts as a whole. Because where there’s an emotional investment, there’s still a will to fight—and as a result, hope and potential for positive change.

That’s all for this week—and, because of the December calendar, for 2017. I’ll be packing, donating, or trashing 12.5 years’ worth of life in Los Angeles next week to head to New York, and the following Sundays are Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve.

Thanks to all my readers for being here with me during this banner year. The Gray Market Weekly will be back in January, with my new gig at artnet News starting on the third.

‘Til then, remember: in some cases, it’s possible to luck your way to the top, but it still usually takes a battle to stay there for long.