Art World

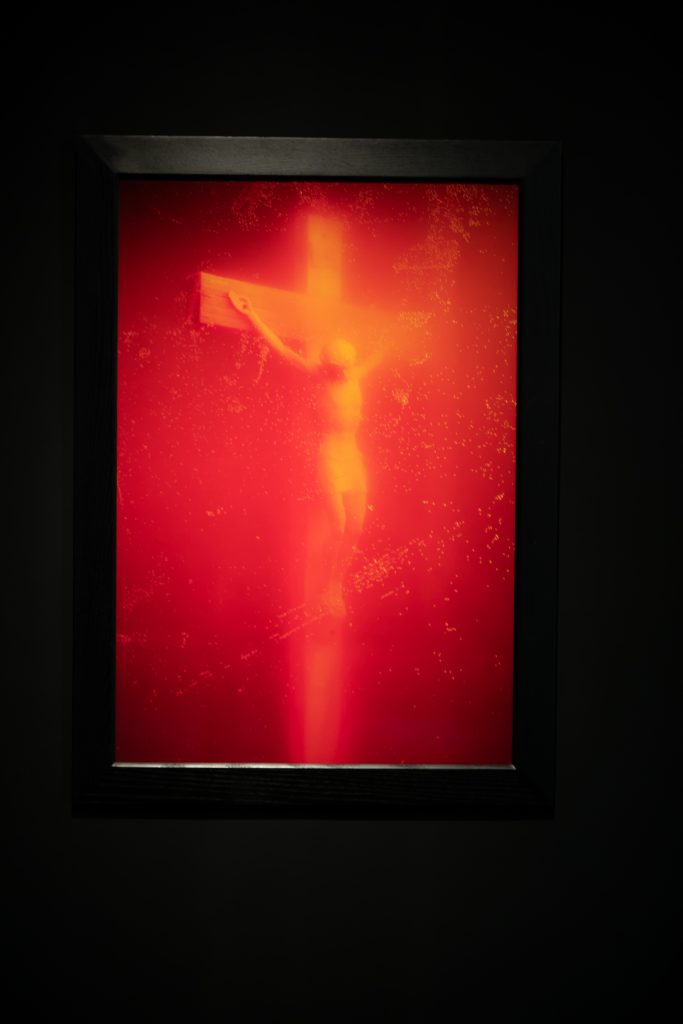

Censored Art Takes Over the Walls of a New Museum in Barcelona

Museu de l'Art Prohibit has more than 200 artworks by the likes of Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, and Gustav Klimt.

Museu de l'Art Prohibit has more than 200 artworks by the likes of Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, and Gustav Klimt.

Adam Schrader

The Museu de l’Art Prohibit, a new museum in Barcelona, seeks to inform viewers about censored art all around the world, using the word loosely to describe everything from social pressure to government restriction.

The museum has been in the works for at least two years, artistic director Carles Guerra said in an interview with Artnet News, after the Spanish media mogul and collector Tatxo Benet acquired a piece by Santiago Sierra from the ARCO fair in 2018. The artist had presented a series of portraits of what he called “political prisoners” after an illegal referendum for Catalan independence led to the arrests of politicians.

“They were considered political prisoners, something that the Spanish sort of neglected and denied,” Guerra said. “By simply saying ‘political prisoners,’ the work caused discussion. In a matter of hours, the work was censored—after Tatxo Benet had already acquired it.”

Collector and media mogul Taxto Benet is pictured with Museu de l’Art Prohibit director Rosa Rodrigo. Photo: courtesy of the museum.

Since then, Benet has gathered more than 200 artworks by the likes of Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, Gustav Klimt, and many others that have been censored, cancelled, faced forms of suppression, or become the subject of a huge debate. The museum coincidentally opened as recent protests condemned a deal that allowed Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez to grant amnesty to Catalan separatists and secure a second term.

When it comes to how the collection is displayed and put into context, Guerra said that the team came up with an app through which viewers can see media reactions about the controversy surrounding each work, such as television news clips and press releases, using QR codes. In some cases, fragments of such video and audio recordings are played next to the work.

“It’s not that the museum has to tell you which position is the correct one morally.” Guerra said. “All you realize is that there are certain objects that have become problematic.”

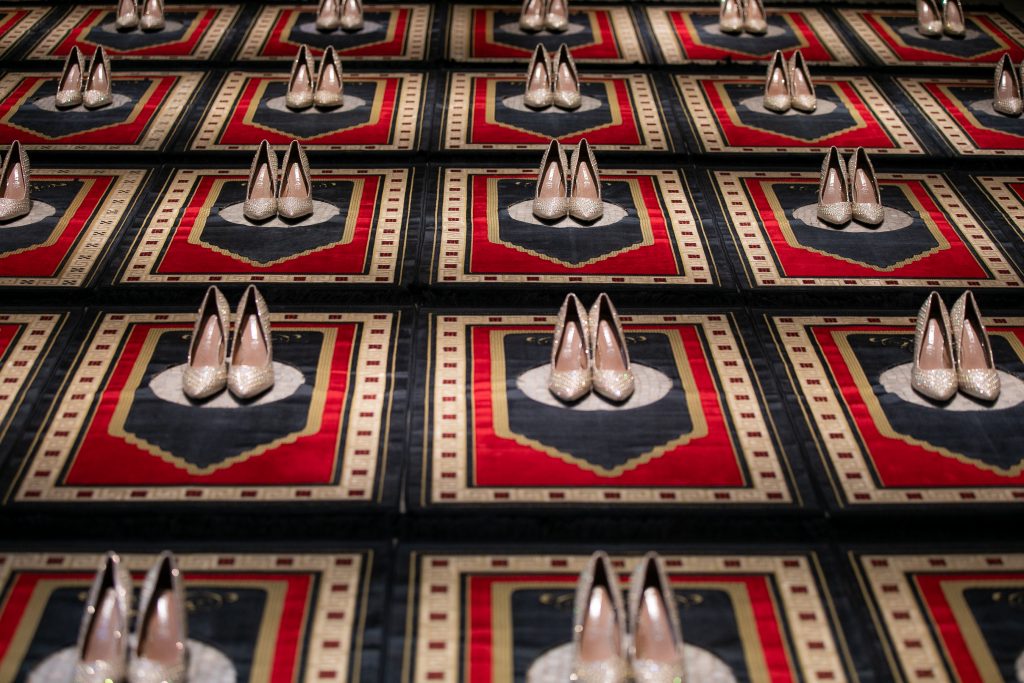

But it’s not just government censorship on view. There are many instances in the collection that show how religious institutions, like the Catholic Church, have fiercely reacted to certain images. One such work on display is Piss Christ (1987) by Andres Serrano, which depicts a crucifix inside of a jar filled with urine. Guerra noted that the photograph has been literally smashed with a hammer by people when it was displayed.

Andres Serrano, Piss Christ (1987). Photo: courtesy of Museu de l’Art Prohibit.

In another work, La Pederastia (2015), the artist Abel Azcona spelled out the word in capital letters using communion wafers he pocketed during hundreds of celebrations of mass.

“It is a piece that even the most critical Catholic people consider blasphemous. And the guy has really suffered. He’s been threatened with death, the artist and his mother,” Guerra said. “When you have these situations, you end up wondering what it is that you appreciate: the beauty of the work itself or the discussion it prompts.”

The artist Charo Corrales created a work depicting the Virgin Mary using her left hand to touch her genitals, which was anonymously vandalized in protest. Corrales never intended to restore the work to its state before the attack, so the museum is now exhibiting the slashed canvas. “This is sometimes the case, that the work has been visibly modified,” Guerra said.

Fabian Chairez, La Revoliución. Photo: courtesy of Museu de l’Art Prohibit.

But he said some forms of censorship on view at the museum are more “sophisticated.” For example, Robert Mapplethorpe’s “X Portfolio” of photographs examining the gay male BDSM subculture in New York was a major flashpoint of the 1970s culture wars in the U.S.

Similarly, the museum has a self-portrait by Chuck Close in response to a show of his work being cancelled at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., after he was accused of sexual harassment. Yet when the Barcelona museum wanted to reproduce this work in the catalog, the artist’s estate denied permission. “A reproduction of the images should be in their interest but because of this cancellation process, they prefer not to,” Guerra said.

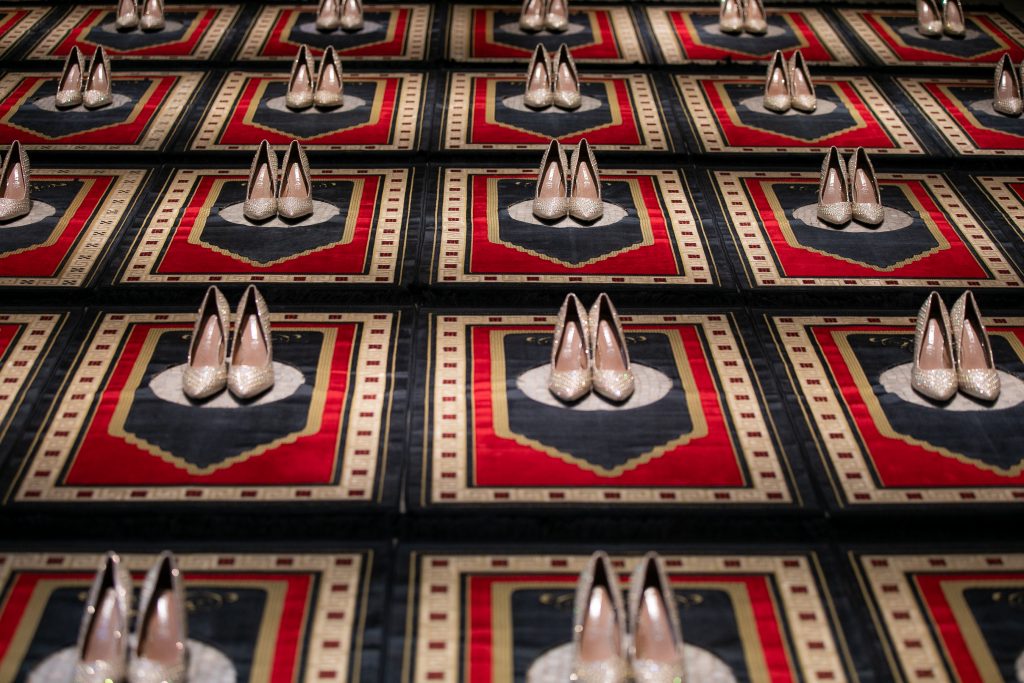

He pointed to similar cases where artists “self-censored.” For example, the artist Zoulikha Bouabdellah created an installation of Islamic prayer mats with a hole in the middle, in which she placed a woman’s high heel shoe covered in glitter. This installation was meant to be exhibited in France after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks, but Bouabdellah was afraid her life could be in danger if she displayed the work. “So far, there’s been no notice or any sort of negative reaction, or any sort of renewed complaint,” Guerra said of its display in Barcelona.

Eugenio Merino, Always Franco. Photo: courtesy of Museu de l’Art Prohibit.

As for the tone of the Museu de l’Art Prohibit, Guerra said some of the pieces initially seem humorous but are darker when thought about more in depth. He gave the example of a sculpture by Eugenio Merino of the late Spanish dictator Francisco Franco trapped in a Coca-Cola brand refrigerator, “as if he were being kept alive.”

“That is a very funny piece. But it also points to the fact that Franco is still very much present in Spanish culture, even though he died back in 1975,” Guerra said. “We have our right-wing parties still celebrating the dictatorship.”

A headline-making portrait by Illma Gore of Donald Trump naked with a “little, little, little, little penis” is also on view, Guerra said. While the picture itself has “nothing of value in it,” it “triggered” supporters of the former president and the artist ended up being physically assaulted.

“It’s not just a normal collection of works valued by either the market collectors or critics,” Guerra said of the museum’s holdings. “It is a completely different form of value-making, and it is a kind of value-change, in which a catastrophe like censorship can make an object far more valuable than it was.”

More Trending Stories:

Art Critic Jerry Saltz Gets Into an Online Skirmish With A.I. Superstar Refik Anadol

Your Go-To Guide to All the Fairs You Can’t Miss During Miami Art Week 2023

The Old Masters of Comedy: See the Hidden Jokes in 5 Dutch Artworks

David Hockney Lights Up London’s Battersea Power Station With Animated Christmas Trees

On Edge Before Miami Basel, the Art World Is Bracing for ‘the Question’

Thieves Stole More Than $1 Million Worth of Parts From an Anselm Kiefer Sculpture