Law & Politics

A Dealer Who Called Out the Art World’s Lack of Due Diligence Is Himself a Victim of Lisa Schiff’s Alleged Ponzi Scheme

Parallels between two blockbuster lawsuits involving art fraud raise questions about "best practices."

Parallels between two blockbuster lawsuits involving art fraud raise questions about "best practices."

Eileen Kinsella

Is the old adage “practice what you preach” not applicable to the art world?

Recent legal proceedings highlight how apparently difficult it can be even for those steeped in the art market to consistently follow that advice.

A prominent New York dealer who has served as an expert witness in lawsuits concerning art deals gone awry has simultaneously allegedly fallen victim to a fraudulent art advisor, it would appear.

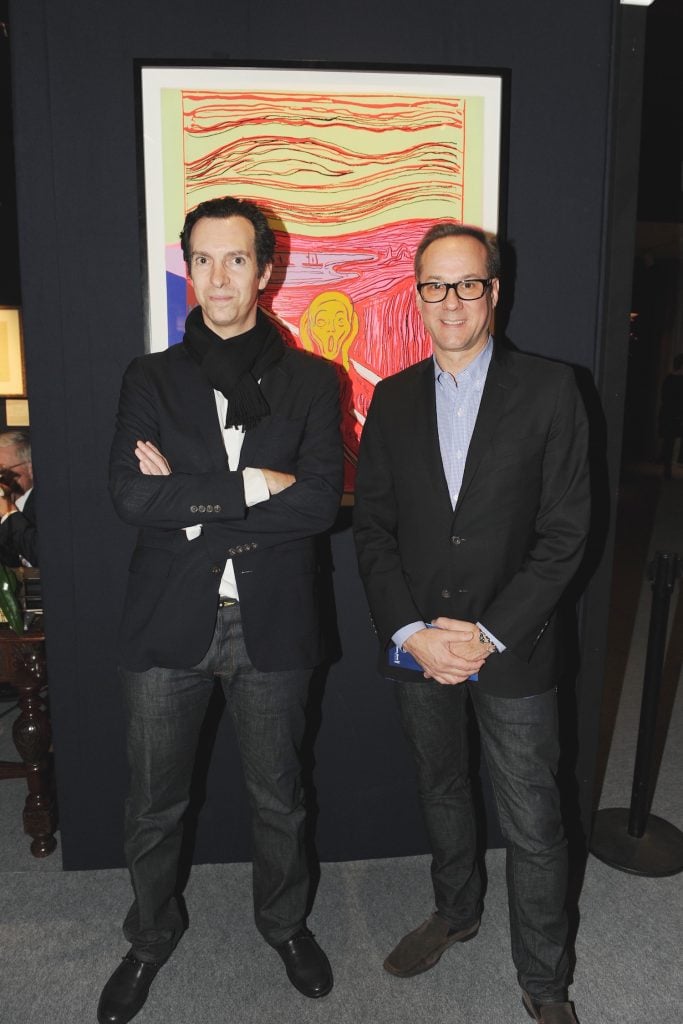

Adam Sheffer is a veteran dealer for galleries including Cheim & Read, Pace, and Lisson, who even served as a president of the prestigious Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) in recent years. He is now a private dealer and advisor.

But, though he was not identified by name, he is referenced in a recent lawsuit that sent shockwaves through the art world. It involves the alleged fraud perpetrated by Lisa Schiff, a high-profile art advisor who has now shuttered her advisory business and has initiated the process of sorting out creditor claims, according to papers filed in New York State Supreme Court.

The suit, which Artnet News reported on earlier, accused Schiff and her business, SFA Advisory, of breach of contract, conversion, fraud, breach of fiduciary duty, and conspiracy. The plaintiffs were identified as real estate heiress Candace Barasch and Richard Grossman and, throughout the complaint, further referred to the involvement of “Grossman’s spouse,” though not specifically by name.

Various media reports and profiles confirm that Sheffer is Grossman’s spouse. The unnamed spouse is not a plaintiff in the case, however.

The plaintiffs are pursuing their shares of the missing profit from a $1.8 million sale of an Adrian Ghenie painting, Uncle 3 (2019), tied to the now-embattled dealer. The suit lays out that Barasch bought a 50 percent stake in the painting and that Grossman and his spouse acquired the remaining 50 percent, or 25 percent each.

A Rudolf Stingel painting from 2012 is at the center of the Philbrick case. Image courtesy Christie’s.

But Sheffer also recently emerged as an expert witness in a separate, long-running legal matter that also scandalized the art world. That litigation, filed more than three years ago, reflects a dispute over a multimillion-dollar Rudolf Stingel painting connected to disgraced art dealer Inigo Philbrick, who sold multiple competing ownership shares in the painting before trying to flip it for profit at a failed Christie’s auction earlier that same year.

In an affidavit dated May 12, Sheffer as expert witness called out a lack of due diligence on a convoluted fractional art flipping deal gone awry.

Sheffer weighed in on a three-way fight for control of the roughly $6 million Stingel, by noting that one of the competing parties, Satfinance, controlled by investor Sasha Pesko, “did nothing to protect its interests, as it neither retained possession of the Stingel Picasso, nor registered its ownership interest via a UCC-1 nor a filing with the Companies House in the United Kingdom.”

The emphasis on due diligence is all the more striking given that Sheffer himself appears to be one of the aggrieved parties, although not a plaintiff, in the suit brought against Schiff. That lawsuit was filed at virtually the same time as the affidavit (May 11), in New York State Supreme Court.

But back to the case concerning the Stingel. In the expert witness testimony, Sheffer addressed the role of FAP (Fine Art Partners), a German-owned art investment company whose claim for the Stingel and other works touched off a firestorm of litigation, and ultimately criminal charges, against Philbrick in late 2019 (Philbrick is currently serving a prison term for the massive $86 million criminal fraud that he masterminded and eventually pleaded guilty to.)

According to Sheffer, as with Satfinance: “The same can be said of FAP: It neither filed a UCC-1 nor a Companies House registration, to thereby give notice to the world, so to speak, of its ownership interest in the Stingel Picasso, nor did it retain possession of the artwork,” according to Sheffer’s affidavit.

While Sheffer took aim at the parties in the Stingel case for not documenting their ownership nor retaining possession of the work, the suit against Schiff for the Ghenie specifies that no one other than Schiff had control or possession of the Ghenie painting after the acquisition was made in 2021.

Neither Sheffer nor his attorney responded to request for comment or questions about whether they documented their ownership interest in the Ghenie. The attorney for Pesko and Satfinance declined to comment.

Sheffer states in his affidavit that he has “concluded hundreds of transactions between galleries and private collectors, museums, and foundations and [is] versatile in understanding the nuance of a variety of types of art transactions depending on the artwork (e.g. primary versus secondary market sales) and type of purchaser (private collector versus museum or foundation.)”

Adam Sheffer and Richard Grossman. Image courtesy Patrick McMullan.

Meanwhile, the particulars of the Schiff case, as Hollywood writers like to say, rhyme with those of the Stingel matter.

According to the Ghenie lawsuit: “Upon completion of the sale, the [Ghenie] Artwork was not delivered to any of the Plaintiffs individually. Instead, through [Schiff] Defendants, it was supposed to have been sent from storage at Crozier Fine Arts to Barasch’s art storage unit at Uovo in Delaware. However, instead of sending the Artwork to Uovo, Schiff caused the Artwork to be sent to Maquette Fine Art’s storage facility in Delaware, with Plaintiffs bearing the pro rata costs of packing and shipping the Artwork. While upon information and belief the Artwork was placed in a storage unit in Plaintiff Barasch’s name, on a day-to-day basis Defendant Schiff controlled the storage unit and what was in it.”

Whether or not anyone filed an ownership stake (and it doesn’t appear that they have) the first Schiff complaint makes clear that she controlled the sale proceeds and failed to distribute them, including that she “exercised dominion and control over the Artwork, thereby seriously interfering with Plaintiffs’ superior rights of dominion and control…[and] exercised dominion and control over sale proceeds from the Artwork.”

The lawsuit asserts that Schiff was emailing “Grossman’s spouse” in early May even as “her extensive business network was imploding as a result of her undisclosed embezzlement of funds and artworks belonging to Plaintiffs, and others—which came to light on Monday, May 8, 2023.”

Sheffer specified that his affidavit in the Stingel case was submitted in response to counsel for Guzzini Properties. Guzzini is a shell company run by billionaire U.K.-based brothers Simon and David Reuben. The Reubens loaned Philbrick $6 million with several artworks reportedly pledged as collateral, including the Stingel. They are among the parties seeking ownership or title to the Stingel following the failed Christie’s sale.

Sheffer, who wrote that his compensation for preparing the affidavit is $400 per hour, added that the compensation “is not dependent either on the opinions I express or any outcome in this litigation.”

More Trending Stories:

A Sculpture Depicting King Tut as a Black Man Is Sparking International Outrage