The Back Room

The Back Room: Value vs. Values

This week: a retroactive wrinkle in a major market controversy, Dakis Joannou does not need a bigger boat, and China goes bonkers for Botticelli.

This week: a retroactive wrinkle in a major market controversy, Dakis Joannou does not need a bigger boat, and China goes bonkers for Botticelli.

Artnet News

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: a retroactive wrinkle in a major market controversy, Dakis Joannou does not need a bigger boat, and China goes bonkers for Botticelli—all in a 7-minute read (2,011 words).

_____________________________

Lisa Schiff, Candace Barasch, Sascha Bauer, Carol Bove, Gordon Terry

Photo: Will Ragozzino/BFA

Tim here. I’ve been in a lot of odd situations in my nearly 18 years in the art business. As of a few weeks ago, the list includes moderating a panel discussion that was interrupted by an audience member questioning the integrity and values of the panelists… three weeks before that same audience member was sued for allegedly running a Ponzi scheme.

You may have guessed by now that the audience member in question is Lisa Schiff, the once-respected art advisor now facing multiple civil lawsuits seeking millions of dollars in damages for purported fraud, as well as investigations by federal and state authorities (with whom she is reportedly cooperating).

These subsequent ruptures retroactively elevated the episode I’m alluding to from an odd side note to a newsworthy event in itself. And weirdly, what triggered the whole episode was a subject normally considered drier than mummified remains: artwork appraisals.

The incident unfolded at the New York edition of the Art Business Conference on April 26, where I was moderating a panel on art finance. About 30 minutes into the hourlong session, Schiff stood up from her seat in an auditorium full of her peers to interject that there was a larger question about value, procedure, and ethics that needed to be addressed.

Here was her concern, memorialized in the conference’s audio recording:

“I had an auction house appraise a client’s collection for a bank loan, and you took something that had more museum shows and cataloging, that had aesthetic and critical value alongside investment value, but that isn’t trading at auction right now and marked it down in half. And that really scared the shit out of me. Like, what’s happening? Because aesthetic and critical value have to be attached to investment value. And when we start to fetishize them the way they’re being fetishized in the marketplace now, they start to split apart even if it’s there.”

Her line of argument wasn’t entirely a surprise. Schiff wrote an op-ed for Artnet News in June 2022 that took a similar perspective on appraisals for loan purposes. But in both cases, her portrayal of the issues is fundamentally misguided and misleading if taken at face value.

When the average person thinks of appraisals, they tend to think of appraisals of fair market value (FMV). The Internal Revenue Service defined FMV as follows in its January 2023 guidance on determining the value of donated property:

“The FMV is the price that property would sell for on the open market,” meaning “the price that would be agreed on between a willing buyer and a willing seller, with neither being required to act, and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.”

In other words, an appraisal of fair market value is an estimate of the price at which two well informed parties could strike a deal without extenuating pressures like, say, the need to liquidate assets to pay creditors ASAP.

However, the setup of Schiff’s conference question (“I had an auction house appraise a client’s collection for a bank loan…”) made it clear that she was targeting a different type of appraisal: what’s known as an appraisal of marketable cash value (MCV).

The big difference between FMV and MCV is that the latter deducts all the costs required to sell an artwork by reputable means. Those costs would include everything from necessary incidentals like packing and shipping to seller’s fees and/or commissions—a combination that could easily eat up 10 to 20 percent of the sale price.

Art-finance providers (including Sotheby’s and Christie’s) fixate on appraisals of MCV for one reason: to understand how much money they’re likely to end up with if a collector defaults on their loan, likely forcing the lender to try to recoup its cash by selling the artwork put up as collateral.

Aside from art-secured lending, MCV also plays a big role in estate planning and so-called “equitable distribution” scenarios, most often meaning divorce settlements. But outside of these contexts, relatively few collectors or art pros know the jargon or its purpose.

No. Despite an implication in Schiff’s op-ed that FMV acts as some kind of evergreen counterweight to MCV, all good appraisals respond to current market conditions. And while the purchase price is a consideration, it matters much less than what rigorous market comps say about an artwork’s value today.

Linda Selvin, the executive director of the Appraisers Association of America, gave me this overarching guideline for appraisals in a phone interview: “You don’t necessarily want to predict for the future because you have to talk about the present.”

And yes, “the present” is largely based on auction results, because they’re the best evidence of the price that willing, unconstrained buyers will pay for a particular work by a particular artist in a market as close as possible to the one surrounding the appraisal being made.

Still, a steep decline in any appraised value (like, say, the 50 percent drop in MCV that Schiff referenced at the conference) isn’t necessarily an indication of villainy or ignorance. The most innocent version is just a consequence of changing taste. What looks like a fair price for a hot artist today might look like a de facto bonfire of your money a few years later.

The sinister version would arise if an intermediary were to, say, purchase artwork from a gallery on behalf of a client for one price but then lard on an unusually hefty fee before invoicing their client for the same work. In such a hypothetical case, even if an artist were to have maintained a reasonably stable market throughout, any type of exacting appraisal would be substantially lower than the owner’s acquisition price.

___________________________________________________________

Compared to fair market value, marketable cash value will always incite more angst among the uninitiated because it is by definition the more conservative appraisal type. (Remember, MCV is not what the buyer would pay; it’s what the seller would be left with after covering all those expenses, commission, and other fees.)

Purely for conversation’s sake, then, it’s not hard to see why an intermediary who either didn’t fully understand the nuances of appraisals, didn’t like the results relative to the prices they’d been charging, or both, could fixate on MCV as some fresh hellspawn of art-market financialization.

In reality, though, MCV is just a sober, educated, risk-conscious reading of today’s market for a short list of pragmatic purposes. Anyone who wants to last at the upper levels of the 21st century art market would be wise to choose their perspective on the issue with care.

_________________________________________________________

This week’s Wet Paint is still being mixed, so here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

Tech and Legal News

_________________________________________________________

“I don’t bring artworks onto the boat. The artworks on the boat are designed for the boat, and they stay here.”

—Mega-collector Dakis Joannou, explaining the central curation principle inside his Jeff Koons-painted mega-yacht during an extended interview with our own Naomi Rea. (Artnet News)

____________________________________________________________

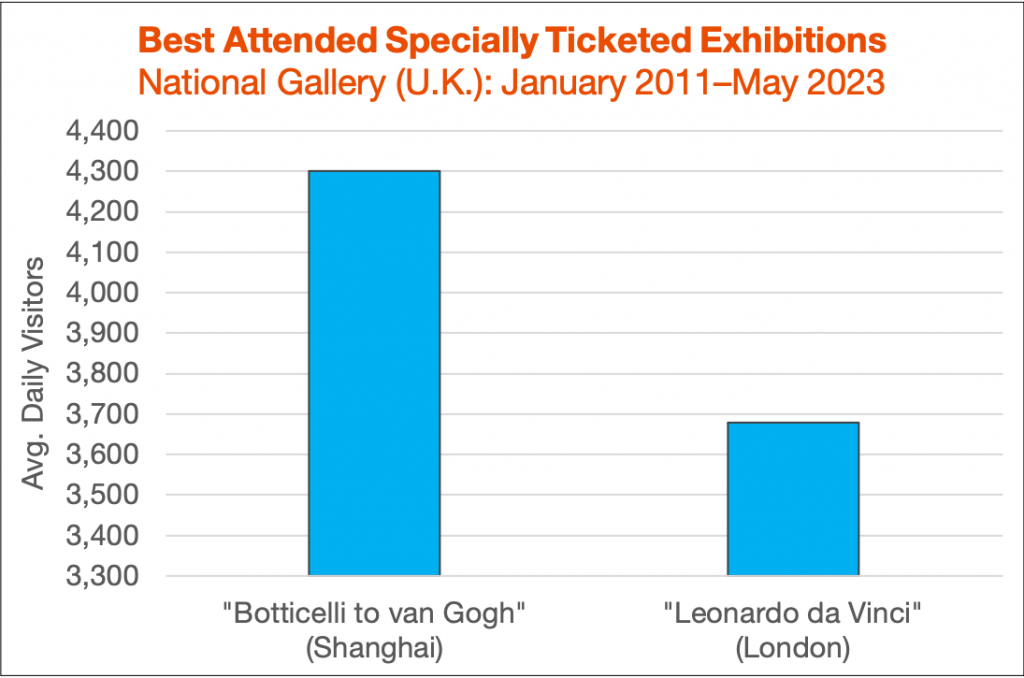

Data visualization © 2023 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

The attendance figures are in for “Botticelli to van Gogh: Masterpieces from the National Gallery, London” and they’ve established a new high for a specially ticketed exhibition staged by the British institution. But the most intriguing aspect of the news is that the record-setting show didn’t take place on U.K. soil at all.

Instead, it was hosted by the Shanghai Museum, which borrowed 52 works from the National Gallery’s permanent collection to assemble a primer on Western painting. The crowds formed early and often to see the results day after day—and paid for the privilege at an impressive scale.

The exhibition is now on view at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul (through October 9), and it will travel to the Hong Kong Palace Museum from November 2023 to early March 2024. Expect the show’s blockbuster appeal to travel right along with it on both stops.

—Tim Schneider

________________________________________________________