In maps rendered “south-up,” the world as we have come to picture it is flipped on its head. Where England and France are usually found, you see Angola and Zambia; South Africa is located where you expect to find Norway. The practice of flipping the map underscores how deeply bias pervades the way we see the world and how often we devalue the “Global South,” a term used to refer to countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Why does the north always have to be centered when the world is a sphere?

For Goodman Gallery, the “south-up” map is the default. The gallery has been championing artists from the Global South since it was founded in 1966 by Linda Givon (then Goodman) in apartheid-era Johannesburg as a “resolutely non-discriminatory space” for black and white artists alike. (The FT notes that, in the early days of the gallery, black guests at openings would have to pretend to be waiters if security forces dropped in.)

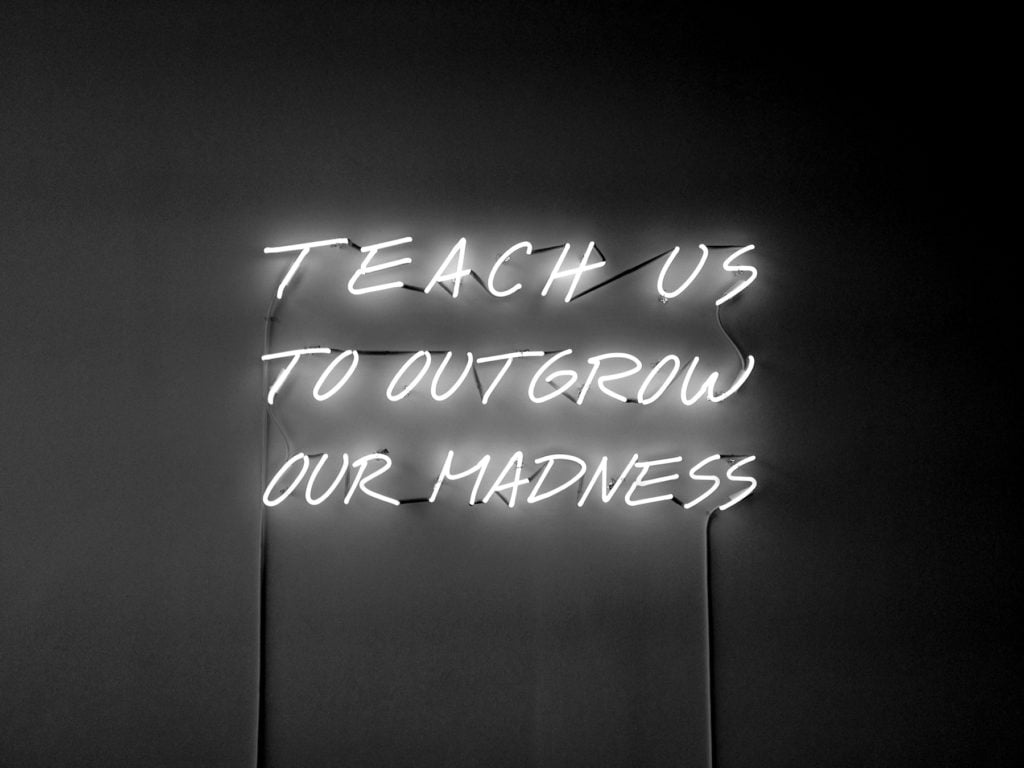

Since Liza Essers, an independent filmmaker turned art dealer, took ownership of the gallery in 2008, Goodman has expanded its international program, with a particular dedication to artists concerned with social change. This week, Goodman is opening its third location—and its first outside South Africa—in London. The gallery’s highly anticipated 22-person inaugural group show at Cork Street brings together work that examines social healing, including Alfredo Jaar’s 1996 light piece Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness and works by Carrie Mae Weems, William Kentridge, and El Anatsui.

Essers stepped away from the putting the final touches on the London gallery to speak to artnet News about why Brexit and rising European nationalism made it the perfect time to open in London, why art fairs can feel “totally soul-destroying,” and why it’s just the beginning for the art market in Africa.

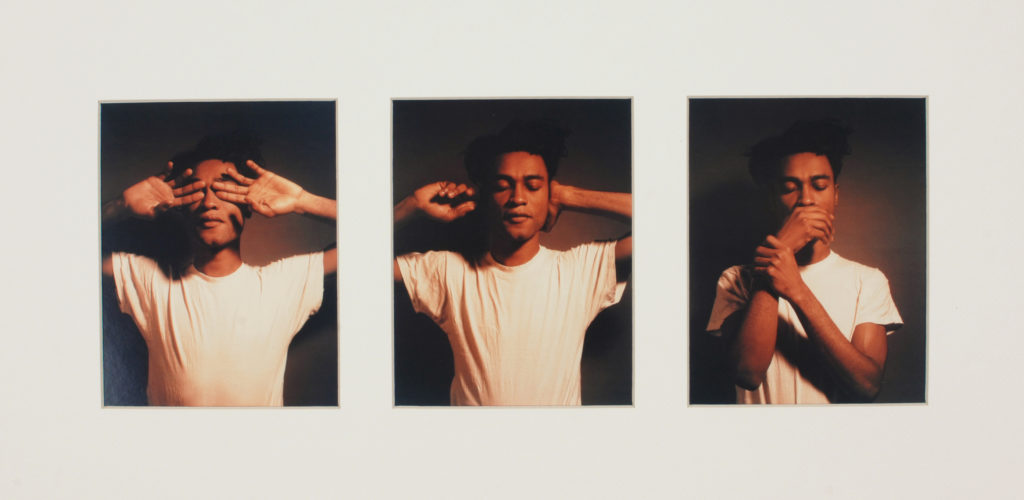

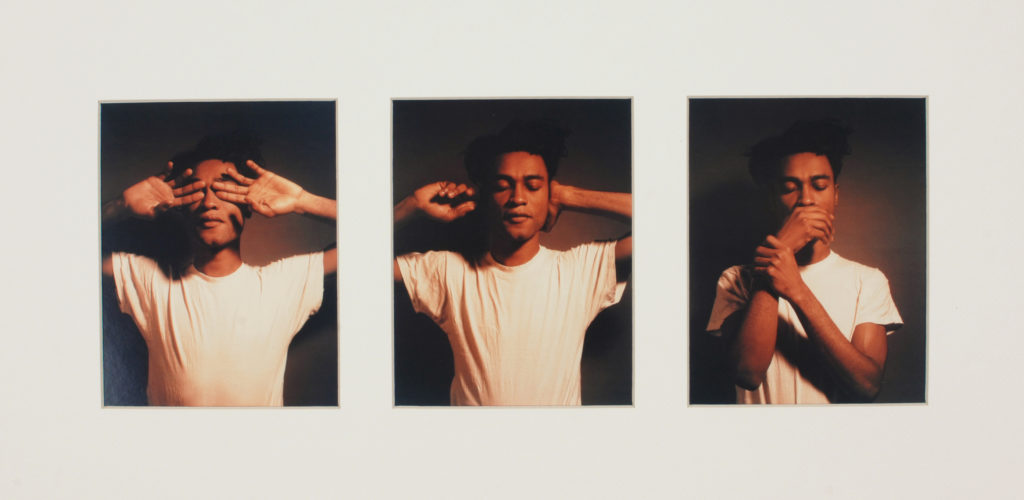

See No Evil Hear No Evil Speak No Evil by Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

You’re introducing yourself to a different audience than the dedicated one you have developed in South Africa. What considerations must you take into account when building your inaugural program in London?

Goodman Gallery’s program has been an international one. That was important to me when I took over the gallery in 2008. We had been working with artists from all over the continent, as well as international artists from the US and from the Global South. We hope that it will become clear what we stand for: We work with artists who are interested in social change and artists that confront entrenched power structures, no matter where they are from. This will continue to be the focus of the program in London.

The opening group show takes its title from artist Gabrielle Goliath’s work about gender-based violence in South Africa, I have grown roses in this garden of mine. You will be bringing up issues that might not be top of mind for people in London.

South Africa has seriously unfortunate statistics with regard to gender-based violence. There is a huge awareness that is happening there, and our reality is a very, very tough one. Women are standing up to gender-based violence, and, of course, it is echoed through movements like #MeToo worldwide. But in South Africa, we have been grappling with urgent questions around social repair for many years, and I think it is something that is relevant globally in terms of our history as a society.

Gabrielle Goliath’s This song is for… Installation view. Photo: Maksim Belousov. Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

What made you choose to open in London? Amid the impending reality of Brexit, did you have any doubts?

No. London will always be an important center for the arts. For us, it was critical to move to the UK in order to have closer to proximity to UK and European institutions. I think it will remain an important center for the global art world, and we will help fight the good fight to ensure that we are part of the discourse, and focusing people on diverse perspectives and social cohesion. It’s important to enter London and Europe at this time, where there is a rising tide of of right-wing nationalism. We can play a role in confronting it.

Part of your program includes live music performances and events by artists and musicians. Why is this a priority—is the goal similarly to widen the public’s perspective on how they can experience art?

Very much so. Goodman Gallery Johannesburg is very focused on art in public space, projects that go beyond the gallery walls. We hope to continue this type of programming in London. It’s very exciting to be premiering [Zimbabwean artist and activist] Kudzanai Chiurai’s film, We Live in Silence, a work disrupting what the artist refers to as colonial futures, with a large live score during our Frieze Week opening.

El Anatsui’s Horizon (2016). Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

I am curious what you think of the rising interest in identity-based art—art where the work hinges on the individual’s identity being reflected through its subject matter.

It’s great that you raise that question. I think that it is really problematic, especially when the trend is based on political and economic constructs and driven by market speculation, which is really a counterpoint to what art is. Art is a global language, and framing artists geographically or by identity is incredibly problematic. It is also something that I find comes up all the time, and it’s a matter of constantly trying to educate people and shift them away from really undermining political and economic ideas.

You will be changing your booth presentation three times during the course of Frieze. Why?

We really wanted to show more of what our program stands for in the art-fair context. Globally, we have seen that fairs are places to sell ideas and that they can contextualize a gallery program. This is why we wanted to try a different approach.

I noticed that you are highly selective about the fairs that Goodman Gallery attends.

We really are far away. It is hugely costly for us to do international art fairs, especially with a weakening South African currency. But I also do feel that the art fair model as it currently exists, being in every city in the world, is just totally soul-destroying. I am more interested in being at home and focusing on our programming locally, which feeds back into the cultural landscape where the gallery is.

Of course, fairs are also critical ways of galleries to engage with international audiences, particularly when you are from South Africa. So we are very reliant on the Basels and the Friezes. But also, being a mother and having a small child, one has to try to create some sort of a balance.

David Goldblatt’s Eyesight testing at the Vosloosrus Eye Clinic of the Boksburg Lions

Club (2_28640) (1980). Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

How would you describe the market for African contemporary art? Is there an imbalance in the kinds of collectors that are now, maybe suddenly, gravitating toward works from the continent?

More and more, we do have to work to make sure that key artworks are placed in museum collections or in the right hands to avoid speculative trade. The art market in South Africa is growing very rapidly, but it remains relatively small compared to the global art market. There are an increasing number of collectors on the continent buying, but there is no question that there are many more collectors interested globally, so a number of great works do end up leaving the country.

However, more and more institutions are opening on the continent that are acquiring important works. And it was extremely exciting at Art Joburg this year, seeing such a diverse and new collector base show up at the VIP preview. There has been a significant shift.

Alfredo Jaar’s Teach Us To Outgrow Our Madness (1995). Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

Our fall 2019 edition of the artnet Intelligence Report examines several art hubs that are emerging in Africa right now. There is a lot of speculation around what these art scenes will look like on the continent in 10 years, and which might emerge as the global meeting point for the trade, the way Hong Kong has emerged in Asia. What’s your take?

There is a massive, growing collector base on the continent, and I think that this will just continue. If I look back at where we were 10 years ago, it becomes clear to me that the market as we know it is really only just beginning. Looking forward another 10 years, it is important to remember that we, too, are at the center, as well, and a part of global discourse. Many artists from the Global South can and will be written into art history for the long run. It will not just be a passing, fashionable moment.

The art world is facing major challenges. The way that things have been working are no longer working, and there are important questions swirling around how the art industry will face all manner of problems, from climate change to problematic patronage—the list goes on.

I think the critical survival tool will be collaboration. There needs to be a shift, because it has been very much about the market recently, and I think we need to go back to art centered around making a difference in society. And through collaboration between artists, galleries, and institutions, we can create a counterbalance. In that sense, I am really looking forward to collaborating with as many people as possible in our new location.