Art World

What Does Hito Steyerl’s Power 100 Ranking Say About the Art World?

ArtReview’s anointing of Steyerl feels beacon-like in the current moment.

ArtReview’s anointing of Steyerl feels beacon-like in the current moment.

Hettie Judah

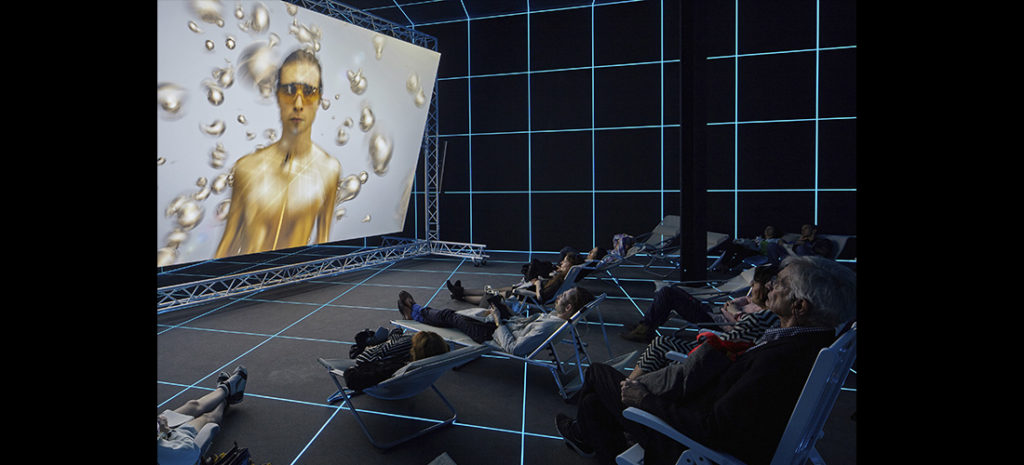

The evening after Hito Steyerl topped ArtReview’s annual Power 100 ranking, a devoted queue formed to view the German artist’s work Factory of the Sun at the opening of a group show at the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Foundation in Turin. (By curious coincidence, the exhibition itself, “Like a Moth to a Flame,” saw ArtReview’s editor-in-chief Mark Rappolt moonlighting as co-curator.)

Factory of the Sun is a widely shown work—a debut at the 2015 Venice Biennale has been followed by prominent outings across Europe and at the Whitney in New York—nevertheless it had the art world standing in line, even in a large exhibition heavy on hits.

In a list prioritizing influential ideas (the second and third positions are occupied by artist Pierre Huyghe and theorist Donna Haraway) Steyerl’s new Power 100 ranking merely reflects the buzz that already exists around this artist, theorist, and influential educator. This summer she presented Hell Yeah We Fuck Die at Skulptur Projekte Münster, a characteristically engaged and powerful work that touched on computer simulations, automated warfare, and life on the ground in the Turkish city of Diyarbakir.

As a public speaker, she offers forceful address on issues ranging from Freeport storage units to Artificial Intelligence. A collection of these talks, together with her essays on politics, technology, and contemporary culture for e-flux journal, have just been published as Duty Free Art. Through her research into conflict, commerce, and the tangled connections between them, Steyerl helps sets the agenda for current art world discourse.

“I think art’s role is to investigate the way things are seen and comprehended—the lenses through which people see things,” she explained when I interviewed her for The Guardian last month. “I never tried to be an artist: until this day I’m never sure whether I ever managed to become an artist, maybe I’m no artist whatsoever. I’m essentially a filmmaker: I was trained to take account of the context I’m working in, including the technologies I’m using and the whole field. Basically I transferred this point of view to the field of art.”

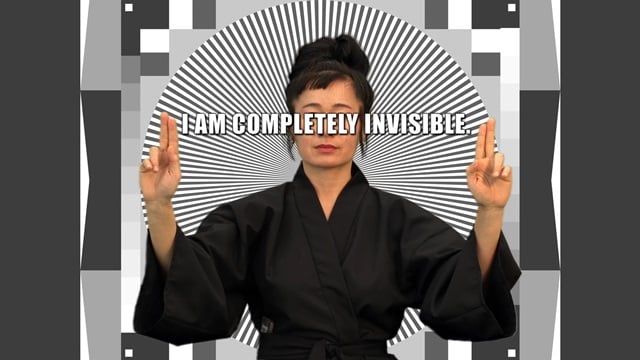

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, (2015). Photo: Manuel Reinartz courtesy ARS17

Steyerl’s interest in the context of her work extends from the site of its production to the circumstances of its exhibition. Following the death of a childhood friend, killed as a member of the PKK (Kurdistan Worker’s Party) in Turkey, Steyerl has made a number of works with peers based in the disputed territories near the Turkish/ Syrian border. Discovering that an exhibition she was in had been sponsored by a weapons manufacturer, she worked with fellow artists to draw up a due diligence contract for exhibition makers to protect against contemporary art being used to generate positive PR for ethically questionable entities.

ArtReview’s anointing of Steyerl feels beacon-like in the current moment. In an era when many people feel impotent in the face of corrupt cultural systems they cannot challenge, Steyerl takes a stand. As conservative commentators deplore the superficiality of the millennial generation, Steyerl’s popular status is a reminder that big ideas still have the power to excite and to move.

What ever Steyerl might make of this ranking, in the month of #Notsurprised, to have a woman so critical of exploitation and the brute force of money within the art world top the Power 100 list feels like a stand for an alternative understanding of power rooted in intellect and integrity.