Art & Exhibitions

How Artist John Akomfrah Used Archival Film Footage to Tell the Forgotten Story of African Soldiers in the First World War

The artist has created an elegiac film for the anniversary of World War I.

The artist has created an elegiac film for the anniversary of World War I.

Javier Pes

The British artist John Akomfrah dug deep into film archives around the world to create an elegiac tribute to the millions of largely forgotten black men from Africa and the United States who fought and died in World War I.

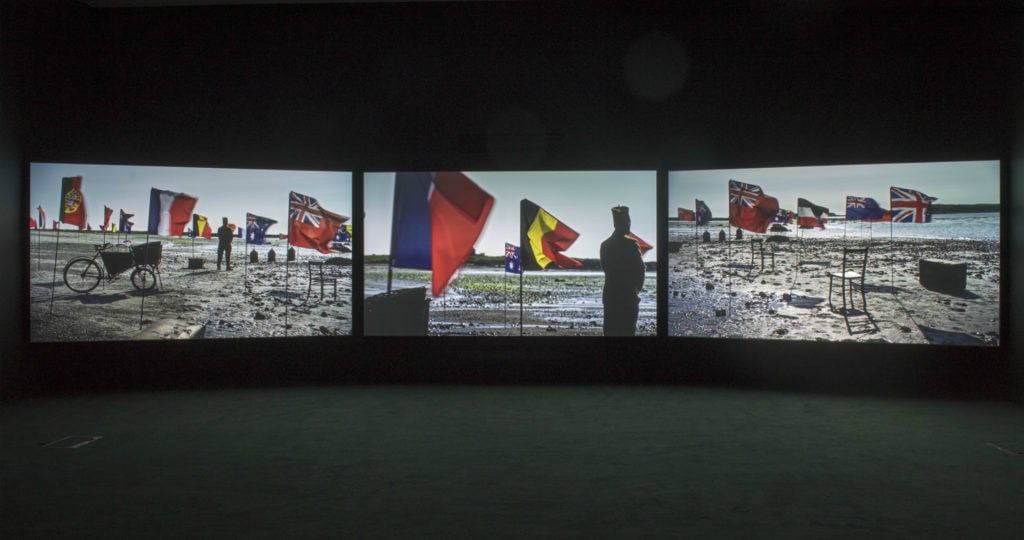

Akomfrah’s epic, multi-screen installation weaves together historic footage, new material, and tableaux reconstructions to explore how the conflict shaped lives around the globe, including those who have largely been written out of Eurocentric portrayals. (Akomfrah’s film, titled Mimesis: African Soldier, makes David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia seem parochial.)

Akomfrah and his team worked right up until the night before the press preview to finish the ambitious 75-minute production, which debuts to the public today at London’s Imperial War Museum. The film was commissioned by 14-18 Now, the UK government-backed group that commissions art to commemorate the conflict.

The film follows uniformed men—some holding shovels and pickaxes, others rifles—as they travel from their faraway homes to the Western Front. The work is based on the true but largely untold story of tens of thousands of men who volunteered to fight or serve as laborers on both sides of the war at a time when both Britain and Germany controlled vast territories in Africa. Almost half of the 100,000 deaths of British forces during the East Africa campaign came from Kenya alone.

Although the team visited the sites of famous battles, including Ypres, Passchendaele, and Verdun, they filmed elsewhere. “I decided to find ‘virgin’ territory to restage our version of what happened,” Akomfrah tells artnet News. “It seemed wrong to ‘play games’ in places that are cemeteries.”

Akomfrah had originally planned to focus only on soldiers and porters from Africa (hence the title Mimesis: African Soldier). But as he continued his research, he decided to include black soldiers from the US, Indian troops and men who came from colonized territories in the Far East as well. “It became clear that the treatment of people of African heritage was markedly similar” to those of African people, he says. “The humiliations and the abuse you suffered as a person of color made no difference if you were a black American or an Egyptian or Senegalese.” To that list he adds Cambodians and Vietnamese, who were under French rule.

John Akomfrah, Mimesis: African Soldier (2018), courtesy of Smoking Dog film and Lisson Gallery.

Key scenes in the film show historic, black-and-white footage of black laborers transporting supplies and ammunition to the front lines and digging trenches. Other sequences show photographs and artifacts floating in the sea, a reference to the SS Mendi disaster of 1917, when a ship filled with troops collided with a steamship in the English Channel, killing more than 600 black South African members of the Native Labor Corps and 30 crew.

Akomfrah’s editing of archival footage conveys something of the individual hopes and fears of the men. “When you have the archive footage 30-feet across, people can see expressions,” Akomfrah says. “You look at them and they are looking at you.”

Like the artist’s Vertigo Sea (2015), a panoramic look at the slavery, migration, and conflict that played out across the sea that was a standout at the Venice Biennale, Mimesis is an absorbing, impressionistic journey. (Next month, both works will be on view in London; Vertigo Sea will be included in the New Museum’s pop-up show.)

John Akomfrah, Mimesis: African Soldier (2018), courtesy of Smoking Dog film and Lisson Gallery.

Akomfrah hopes Mimesis will offer geopolitical context for viewers who may have grown up misunderstanding the war’s scope. “Many of the great anti-colonial figures in the 20th century all fought in the war,” he says. “Ho Chi Minh, for instance, came through the European theater.” Fighting side by side, colonial subjects realized that Europeans were no better than them, he notes. The film starts with a quote by the Polish-German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg: “Those who do not move do not notice their chains.”

Akomfrah has a family connection to the war, albeit an indirect one. His Ghanaian grandfather moved to rural Nigeria in the 1920s to take up a clerical post. He met Akomfrah’s grandmother there. “I remember him telling me when I was very young, ‘I only got this job because all these people died in the war and they didn’t have enough white people.’”

Mimesis: African Soldier is on view from September 21 to March 31, 2019, at the Imperial War Museum, London. It will travel to New Art Exchange in Nottingham next fall.