People

More Than Two Decades After Her Death, the Great Singaporean-British Artist Kim Lim Is Finally Being Written Into Art History

The late sculptor and printmaker is the subject of a solo display at Tate Britain.

The late sculptor and printmaker is the subject of a solo display at Tate Britain.

Naomi Rea

You may not have heard of the late Singaporean-British artist Kim Lim. But that is about to change.

More than 20 years after her death, the sculptor and printmaker is the subject of a spotlight display at Tate Britain in London, one of a series of exhibitions that are re-evaluating her legacy as institutions look to expand art history’s narrow narratives.

Although she is not a household name today, Kim Lim was a significant player in the artistic landscape of postwar Britain. Her minimalist works were indebted to modernism and embodied a multicultural perspective that preceded the UK’s transformation into the cosmopolitan society it is today. Now, curators are looking to write her back into the history books.

Over the past two years, the artist has been the subject of solo shows at Sotheby’s S|2 Gallery in London, Manchester Art Gallery, and STPI in Singapore. Institutions including Hong Kong’s M+ museum and the National Gallery of Singapore have been snapping up her meditative works on paper and spare, organic sculptures.

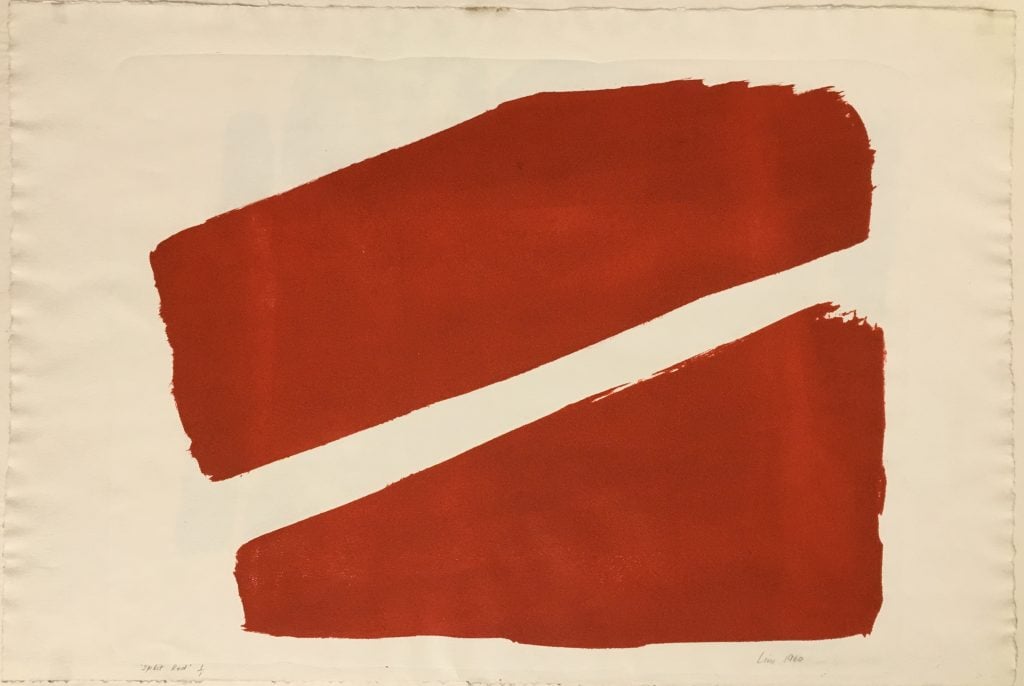

Kim Lim, Split Red (1960). The Artist’s Estate, London. ©Estate of Kim Lim. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020.

Kim Lim came to the UK from Singapore at 17 to study art—a relatively bold move for a young woman at the time.

“Kim Lim faced many obstacles,” the show’s curator Elena Crippa tells Artnet News. “She was Singaporean and a woman at a time when the art world in Britain was even more afflicted by systemic racism and sexism.” It did not help that she chose the unconventional—and widely considered “macho”—form of sculpture as her artistic medium.

Lim’s artistic language drew on both her cultural and geographical roots in Southeast Asia and her deep knowledge of Western art history. But like many other artists from former colonies who worked in Britain in the postwar period, she was not thoroughly integrated into Britain’s art-historical narratives by scholars. Which is not even to mention the distraction provided by her famous husband—the late sculptor William Turnbull.

Kim Lim, Sphinx (1959). The Artist’s Estate, London. Photograph taken by the artist © Estate of Kim Lim.

For years, she shared the fate of many pioneering female artists who are now gaining overdue attention such as Lee Krasner, Anni Albers, and Leonora Carrington: her own work was often sidelined and she was wrongly relegated to “muse” status.

The exhibition at Tate (notably, the same institution that organized a major Anni Albers show in 2018) includes 20 prints and sculptures dating from the late 1950s to the mid-’70s. At a moment when institutions are trying to decolonize the history of art presented in galleries, Crippa says that the Tate show is part of a larger institutional effort to “conceive of new narratives that present the history of British art as marked by reciprocal connections and influences across different regions, nations, cultures, and social classes.”

While the Tate show represents a significant moment, Bianca Chu, special projects advisor to the Kim Lim Estate, says it is important to remember that despite being relatively overlooked and commercially undervalued in recent decades, Kim Lim’s work was appreciated in her time.

“While the new momentum and recognition of Kim Lim’s life today is very much deserved, during her lifetime, Lim was not an unknown artist,” Chu says.

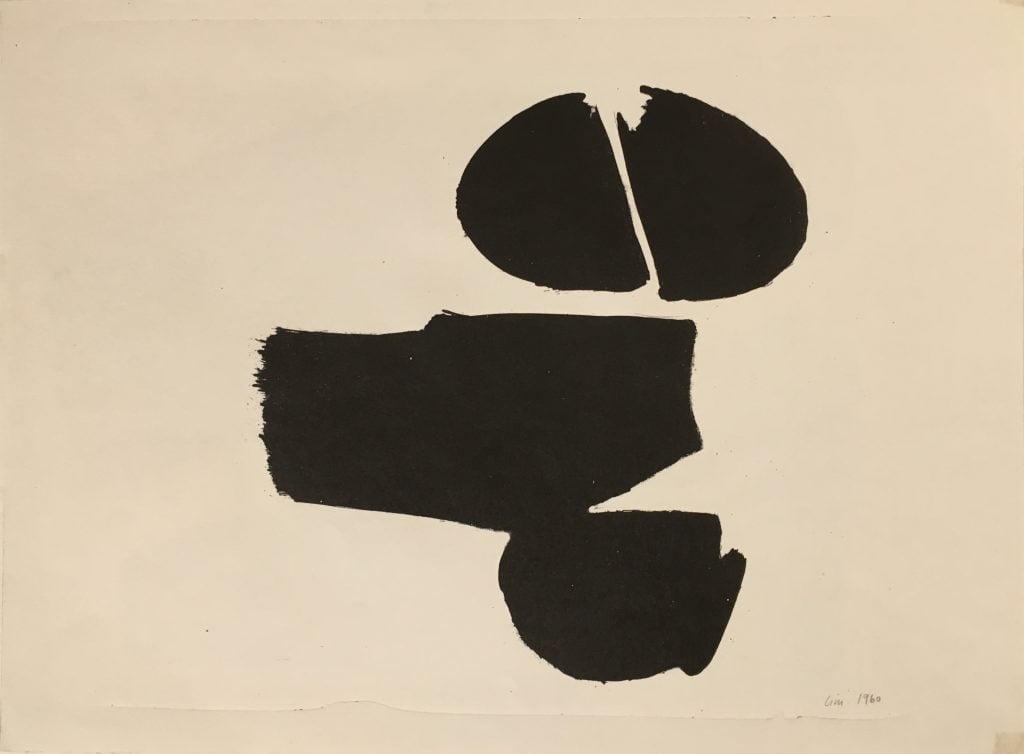

Kim Lim, Sphinx (1960). The Artist’s Estate, London. ©Estate of Kim Lim. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020.

Lim’s work was exhibited as early as 1966 in London and steadily supported and collected by institutions of the era. It appeared in a number of important group and solo exhibitions during her lifetime, including the 1977 Hayward Annual, in which she was the only non-white and female artist to be featured; her first major mid-career retrospective was held in 1979 at the Roundhouse. Her work is in the collections of major museums including the National Gallery Singapore, Tate’s London and Liverpool galleries, Fukuyama City Museum in Japan, and the Arts Council Collection in the UK.

Although she was an immigrant to the UK, Lim was stubborn about not wanting to be seen as “other”: She declined an invitation to be a part of the Hayward Gallery’s now-famous 1989 exhibition “The Other Story,” which shined a light on the African and Asian artists working in postwar Britain.

Chu says Kim Lim’s work was in many ways “ahead of its time,” preceding the multiculturalism that defines our increasingly globalized society. She was part of an international art scene that emerged within the localized creative community of postwar Britain alongside contemporaries Rasheed Araeen, David Medalla, Jalal Anwar Shemza, and other artists who exhibited at the radical 1960s London gallery, Signals. And at long last, she is earning her rightful place in history.

“Kim Lim: Carving And Printing” is on view through April 5, 2021 at Tate Britain, London.