On View

Korean Modern Master Lee Jung Seob Finally Gets His Due at MMCA

A hundred years after his birth, the artist gets his first major museum show.

A hundred years after his birth, the artist gets his first major museum show.

Sarah Cascone

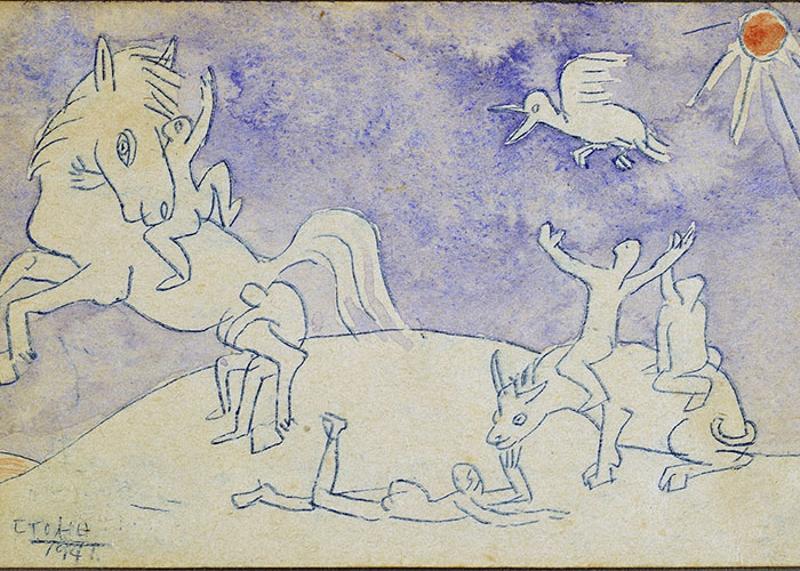

At first glance, the small, seemingly-unobtrusive works on view at Lee Jung Seob‘s retrospective the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Deoksugung, in Seoul, give little indication that the painter is considered one of South Korea’s most important and celebrated 20th century artists.

Lee, who was born in 1916 in what is now North Korea, worked on small canvases and modest sheets of paper, as his poor financial circumstances preventing him from realizing grander visions. As a result, the show is lacking any obvious showstoppers that might catch your eye from across the room. But upon closer investigation, the works reap many rewards.

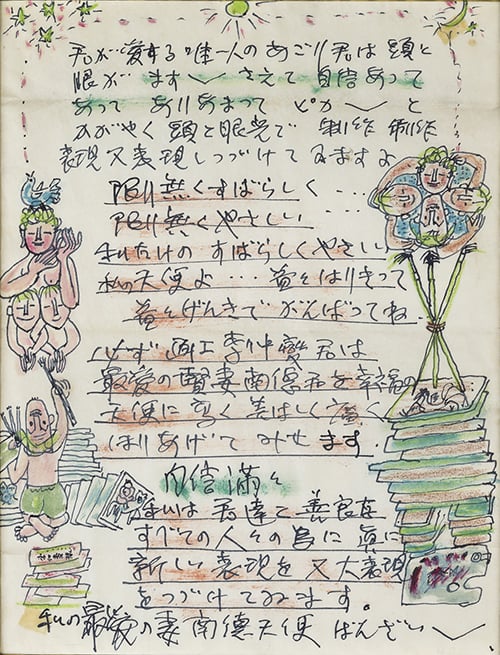

The MMCA has secured an impressive 200 works on loan for the show, including tiny drawings etched on foil wrappers Lee saved from cigarette cartons and richly illustrated letters he sent to his wife and children, as well as more traditional oil paintings, such as the bull paintings for which he is best-known.

Lee Jung Seob. Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

Lee’s short life—he died in 1956 at just 41 years old—was marked by hardship and disappointment. He studied art in both Pyeongan and Tokyo, and was aided by one of his teachers, Lim Yongryeon, who provided Lee with an understanding of both Eastern and Western Art.

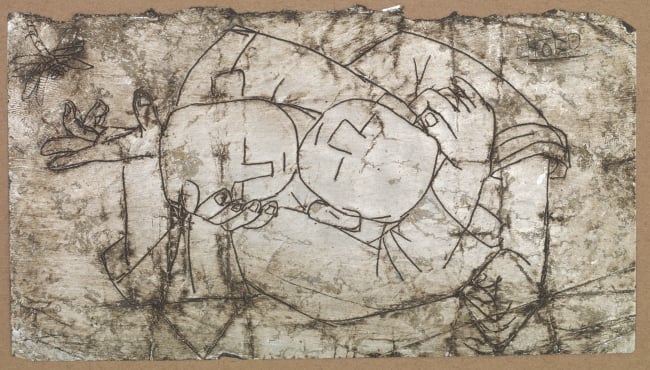

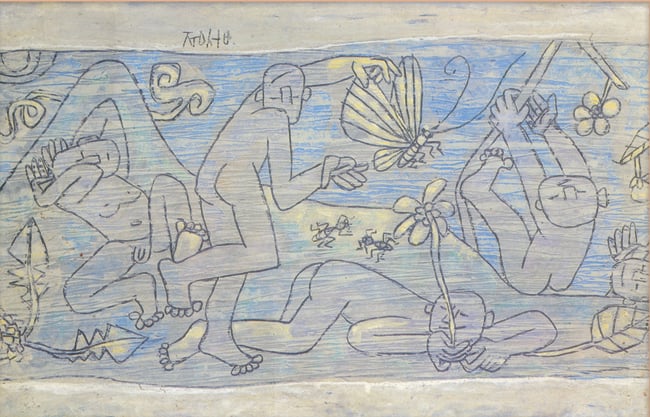

Though his works may be small, Lee’s oeuvre has an undeniable power. While indebted to the traditions of Eastern art, Lee is also credited with embracing the West, drawing on the painting aesthetics of both regions to create an utterly unique blend of the two. His works frequently depict emotional human figures, often captured in a loving embrace, with an economy of line, Lee seems to straddle many worlds.

A letter from Lee Jung Seob to his family. Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

He lived during a turbulent period for Korea, marked first by Japanese colonialism and World War II, and then by the Korean War (1950–53), moving many times over the course of his career.

Lee found love in Tokyo, where he met his wife, but also artistic success, as his work was met with critical praise. He was invited to join the Association of Free Artists, and later formed his own group of Korean artists in Japan, called the Association of New Artists, which held a well-received exhibition in Tokyo. In 1943, during the height of the war, however, Lee returned to Korea.

By 1950, he and his wife and two children had fled to Busan as a result of the outbreak of the Korean War. Lee was forced to leave much of his artwork behind, where it was destroyed by bombing. After two years in refugee camps, with the family struggling to make ends meet during the war, Lee’s wife made the difficult decision to returned to Japan in 1952.

Lee Jung Seob, Two Children (1950s). Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

Struggling financial and devastated by his separation from his family, Lee suffered from depression. He worked hard to sell his work, but despite two solo shows and one group exhibition, Lee never received financial success. The artist tragically died of hepatitis and malnutrition on September 6, 1956, in Seoul’s Red Cross Hospital.

While his genius is widely-recognized in his native country, the current exhibition, which honors his 100th birthday, is actually South Korea’s first major museum show of his work. The MMCA attributes this oversight in part to the fact that many of his works are owned by private collectors, and are not easily brought together in one place.

According to the artnet Price Database, Lee’s record at auction is $2.9 million, set by his oil painting The Bull at Seoul Auction in 2010. Although the press materials from the MMCA note that “many of his works have been repeatedly sold and re-sold for increasingly astronomical prices,” it is his only sale of more than $1 million.

Lee Jung Seob, White Bull (1953–54). Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

Some works seem Grecian, and could just as easily be at home on the side of a clay urn. Others have an Cubist, Picasso-like quality, while still others suggest Henri Matisse’s cut outs and even graffiti, presaging Keith Haring’s signature crawling baby. This makes sense, given that Lee’s generation was the first to engage with Western styles of art.

It’s a body of work that stands apart, from a man who worked prolifically despite personal and professional struggles.

Lee Jung Seob, Children in Spring. Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

Knowing the sad reality of how Lee met his death makes viewing exhibition all the more poignant. Again and again, Lee turned to his family for artistic inspiration, drawing children at play and family members in warm domestic scenes. His goal, he once said, was to be an “honest painter,” and the “painter of the Korean people.” Ultimately, his dual passions, for art and for family, were inextricably intertwined.

“The 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Korean Modern Masters: Lee Jung Seob 1916–1990” is on view at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Deoksugung, 99 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul; June 3–October 3, 2016.