On View

Palestinian Photographers Explore Identity and Displacement in a Poignant New Show

Loss, displacement, and the ever-present threat of violence pervade these personal explorations of life in exile.

Loss, displacement, and the ever-present threat of violence pervade these personal explorations of life in exile.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Israel’s war in Gaza has been documented like no conflict before, with footage filmed directly by impacted civilians and spread rapidly across the globe. For many, especially younger audiences, these firsthand accounts have become a more trusted source of information than mainstream media outlets, which many believe are obscuring the reality in line with their own agenda.

Utilizing this power of the image to cut through the discourse surrounding geopolitical conflicts and bring the focus back to its impact on everyday life, Palestinian artists have long been documenting their experiences, community, and surroundings. In many cases, violence is only obliquely referenced, either by the physical manifestations of occupation, like fences, watchtowers, or a ravaged landscape, or by its psychological aftermath: displacement, grief, longing.

Though the making of art is an interpretative, subjective act, it can unveil truths that may be otherwise impossible to convey. This is certainly what brings together projects by three Palestinian photographers living in exile —Ameen Abo Kaseem, Nadia Bseiso, and Lina Khalid—that are included in a new exhibition, “Longing: In Between Homelands,” at Palo Gallery in New York City, on view through February 8, 2025.

Ameen Abo Kaseem, Untitled. Image courtesy of the artist and Palo Gallery.

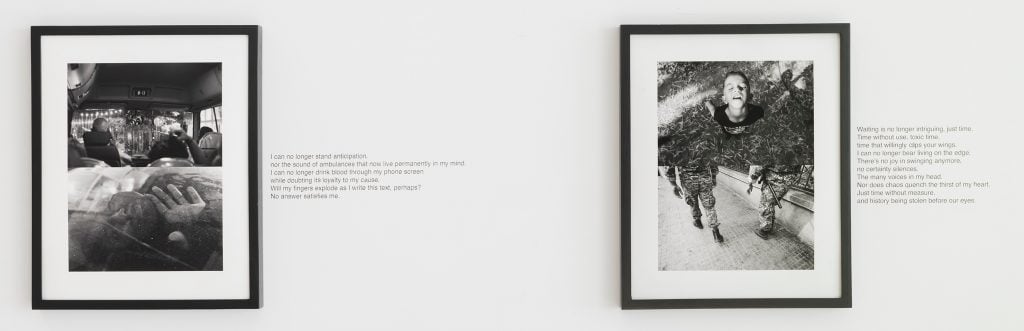

Most of the works by Ameen Abo Kaseem, from a series titled “We Deserved a Better Time on this Earth,” are diptychs that pair joyful snapshots from everyday life, including moments of bliss or affection, with more threatening scenes of chaos on the streets or armed soldiers on patrol.

The Palestinian-Syrian photographer based in Beirut said appearing in the show made “the weight of memory and exile feel shared, not solitary.”

“This work isn’t about giving answers—it’s about holding space for the questions,” he said. “What does it mean to belong when your home exists only in memory? How do we carry the land within us, making it visible even when it feels lost? And how do we keep moving forward, with love and poetry, even in the shadow of exile.”

Installation view of “Longing: In Between Homelands” at Palo Gallery in New York until February 8, 2025, featuring works by Ameen Abo Kaseem. Photo: Thomas Barrett.

Kaseem has also poured his despair into wall texts that accompany the photographs and read as private diary entries. “I wonder: if I were born on the other side of the world, would I be in this same moment?” reads one. “I stare at the ground for a long time, muttering, ‘we deserved a better time on this earth.'” Another reads: “There was never anything I believed in like love, but today I find it a compass pointing to nothing.”

The artist said that he had some trepidation about showing works like these in a commercial gallery setting. “My work is dark, personal, and not the kind of thing that feels ‘sellable’,” he said. “I worried about how it would be received. But hearing people say they’ve connected to these moments and feelings has meant everything to me.”

Nadia Bseiso, Hot Spring (2017). Image courtesy of the artist and Palo Gallery.

The only color images are those by Palestinian-Jordanian Nadia Bseiso, who is based in Amman, Jordan. The works in Infertile Crescent explore the convergence of geopolitical and ecological concerns in a region sometimes known as the Fertile Crescent for the early human civilizations that once flourished there by cultivating its lands. They were mostly made between 2016 and 2018, years leading up to the planned construction of a pipeline that would tackle water scarcity in the Middle East by moving water from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea.

As such, the works often take as their subject diverse water sources native to Jordan and scenes of everyday life and survival in the Jordan Valley. The pipeline, which was criticized for its potential damage to natural ecosystems, was eventually abandoned. The Jordanian government cited a lack of interest from Israel, which had originally agreed to help fund the project.

“As Palestinians in the diaspora, we remain connected to our homeland by an invisible umbilical cord,” said Bseiso. “Even if we have man-made borders, whatever happens in Palestine hits close to home.” She added that Infertile Crescent was a way to capture “how invisible lines, geopolitics, conflict, and water scarcity [have] dictated how we lived in the region and how they are responsible for shifting the area from what it once was, to what it is today, and what it might soon become.”

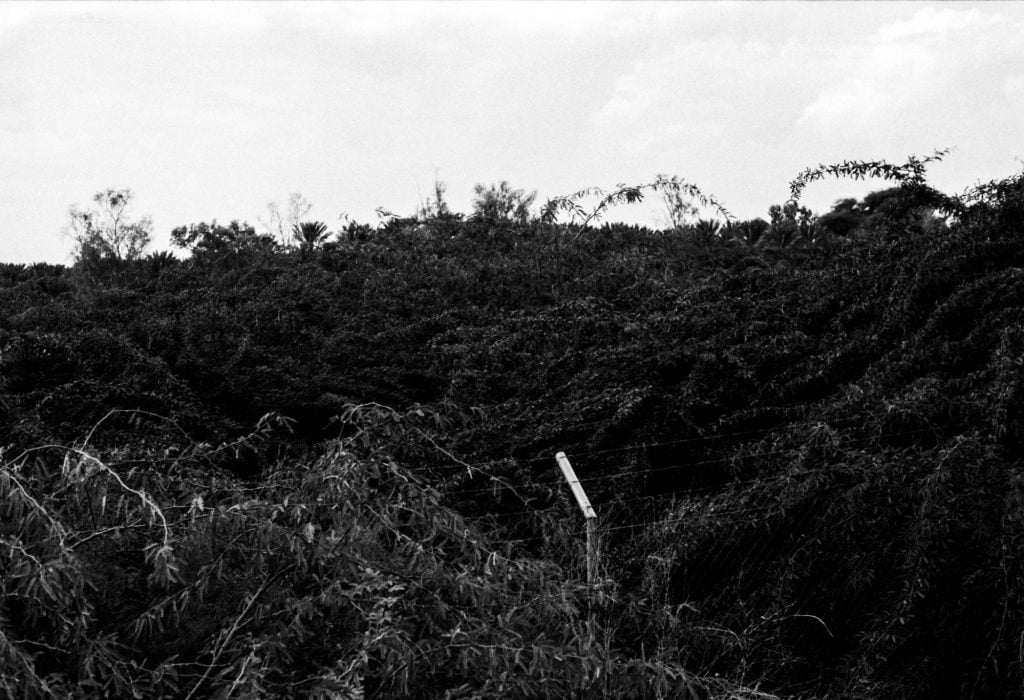

Lina Khalid, 75-300mm (2024). Image courtesy of the artist and Palo Gallery.

Lina Khalid, who moved to Jordan as a Palestinian refugee and now lives in the capital of Amman, grew up forced to only know her homeland from afar. On family trips to the Dead Sea, she could just about make it out in the far distance.

In the black-and-white photographs of To Look Over there is a Sin, Khalid explores the complexity of this apparent proximity in a landscape scarred by manmade borders. In some of her images, these borders interrupt an otherwise timeless and tranquil topography.

Lina Khalid, The Sea is Over There. Do You See It (2024). Image courtesy of the artist and Palo Gallery.

Khalid said the exhibition is “a space to express the profound experiences of loss and transformation that deeply impact our lives as Palestinians born and living in exile.”

She added: “I’m happy to share my experience in navigating the complex relationships between memory, identity, and art as a means of healing and resistance. Each image in the project and the exhibition, featuring my colleagues Nadia and Amin, reflects a moment of contemplation on our personal and collective experiences, forming an attempt to document emotions often lost amid the chaos of reality.”

The three artists featured in “Longing: In Between Homelands” were selected from the Arab Documentary Photography Program, a joint initiative of the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, the Magnum Foundation, and the Prince Claus Fund, which provides mentorship for photographers from the Middle East.

“Longing: In Between Homelands” is on view at Palo Gallery’s second location at 21 East 3rd Street in New York City until February 8, 2025. All proceeds from the exhibition will go directly to the artists.