Art World

9 Works the Met Should Sell Right Now to Avoid Raising Ticket Prices—Forever

Two writers engage in an outlandish thought experiment.

Two writers engage in an outlandish thought experiment.

Menachem Wecker &

Margaret Carrigan

The Metropolitan Museum of Art touched off a wave of outrage last week when it announced that it will begin charging tourists mandatory admission fees in March. The new ticket revenue is expected to bring in between $6 and $11 million a year for the museum, which has an annual budget of $300 million.

Given that the museum estimates the new admission policy will increase its budget by a mere two to three percent, it’s hard to imagine that there were “no other solutions,” as the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott pointed out.

Here’s one: Host a yard sale. Pluck a mere nine works from the collection of two million objects that visitors wouldn’t miss, particularly given that large museums like the Met only display, on average, five percent of their collections at any one time. If those nine objects could raise a dedicated endowment of just over $190 million, it would cover admission for tourists in perpetuity. (We’re assuming it would yield the standard endowment’s annual five percent return, $9.5 million, which is toward the top of the range the museum anticipates it will generate from the new admission policy.)

Deaccessioning artwork is a messy and contentious business with many legal stipulations, meaning that it would, in all likelihood, not exactly be feasible for the Met to nix anything from its collection. Also, there is the pesky fact that museum collections are considered part of the public trust, meaning they are not typically recorded as assets on an institution’s balance sheet.

Nevertheless, as a thought experiment (humor us), we took a stab at identifying nine works the museum could unload to get the maximum bang for its buck without disrupting the integrity of a collection that hundreds of thousands of out-of-state visitors make the trek to see every year. (All of this assumes the museum can’t de-install its fancy $65 million fountains and sell them for parts.)

Here are our picks—let the outrage begin.

Manuscript Leaf with Saint Christopher Bearing Christ (14th century). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Christopher, the patron saint of travelers, would likely give the Met the cold shoulder for its decision to penalize tourists and New Yorkers without I.D. This particular anonymously made miniature from the 14th century, which the Met calls Manuscript Leaf With Saint Christopher Bearing Christ, isn’t on view. But if the Met would like to ironically celebrate the saint, it has plenty of other, finer depictions in its collection, including those by Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach. The fragile work is a relatively recent addition to the museum’s collection (meaning it did just fine without it for more than a century). In July 2009, Sotheby’s sold the manuscript leaf, which it titled St. Christopher holding the Christ Child, for $36,439. The museum acquired it in 2010. Taking inflation into account and the market today, this work should bring the Met about $60,000.

Fictional amount raised: $60,000

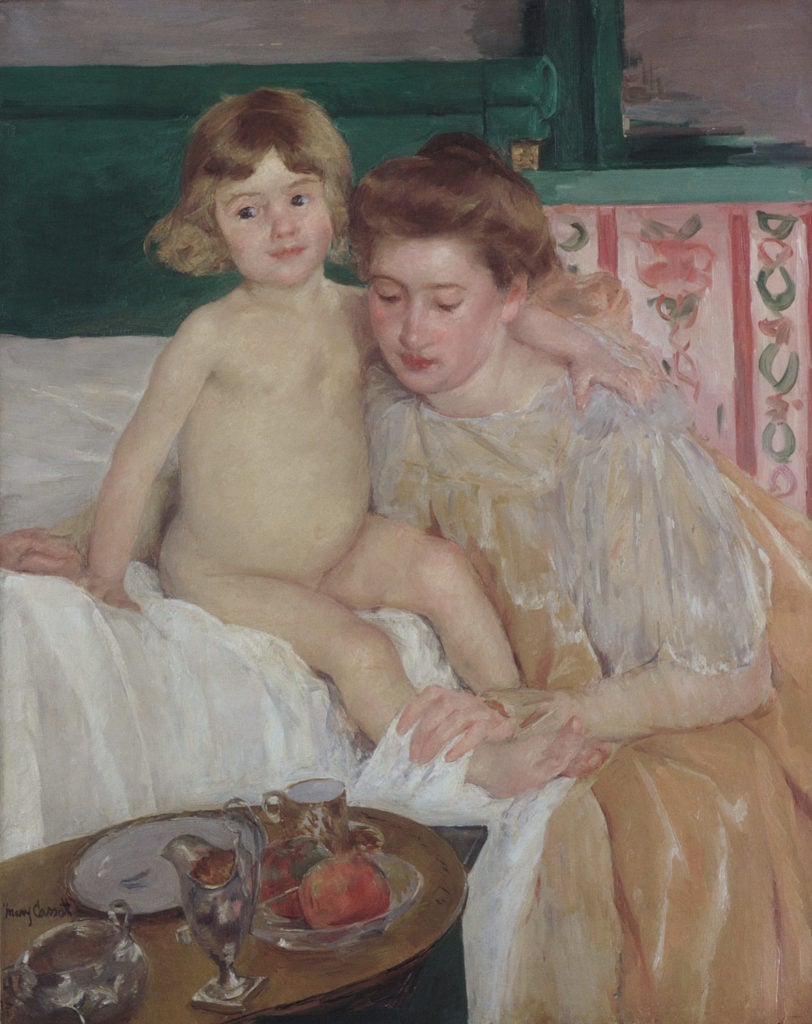

Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child (Baby Getting Up from His Nap) (ca. 1899). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met has 133 works by Mary Cassatt. It likely wouldn’t miss the first one to enter its collection—Mother and Child (Baby Getting Up from His Nap) (c. 1899)—which is sappy even by this artist’s standards. Furthermore, Cassatt has tried to cover up compositional problems with soft brush strokes, the figure on the right appears to have a left shoulder made of taffy, and none of the hands in the picture makes much sense. A considerably smaller work by the artist, Girl in a Bonnet Tied with a Large Pink Bow (1909), sold for $2.3 million last May, and the Met’s picture has two figures, an improvement over the bonneted one. We think it’s safe to add $3 million back to the Met’s bottom line for this one.

Fictional amount raised: $3 million

Georgia O’Keeffe is an indubitable icon in modernist American painting, but many critics have mused on whether her myth outweighs her creative contributions to the history of art. Since the Met holds 30 of her works, perhaps it would do well to offload one of several that isn’t on view, such as Near Abiquiu, New Mexico (c. 1930), a wide landscape of the arid Jemez Mountains, in which the artist nearly anthropomorphizes the hills by making them appear as fleshy lumps set against a sliver of aquamarine sky. Because, let’s face, it, Kay WalkingStick did the panoramic mountainscape better, and the Met only has two of her works in its collection (neither of which is on view, by the way). O’Keeffe’s work sells well these days, as evidenced by the record-setting 2013 Sotheby’s sale of Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, a work the O’Keeffe Museum was deaccessioning for acquisition funds at the time. Three years ago, a picture that is similar, yet inferior to the Met’s sold for $5.1 million, so we surmise the museum ought to get at least $6 million for this painting. At the same time, it could make wallspace for WalkingStick’s Wallowa Mountains Memory, Variation (2004), which it could buy for a fraction of the price—her auction record is just over $1,000—while still shoring up its fictional admission endowment.

Fictional amount raised: $6 million

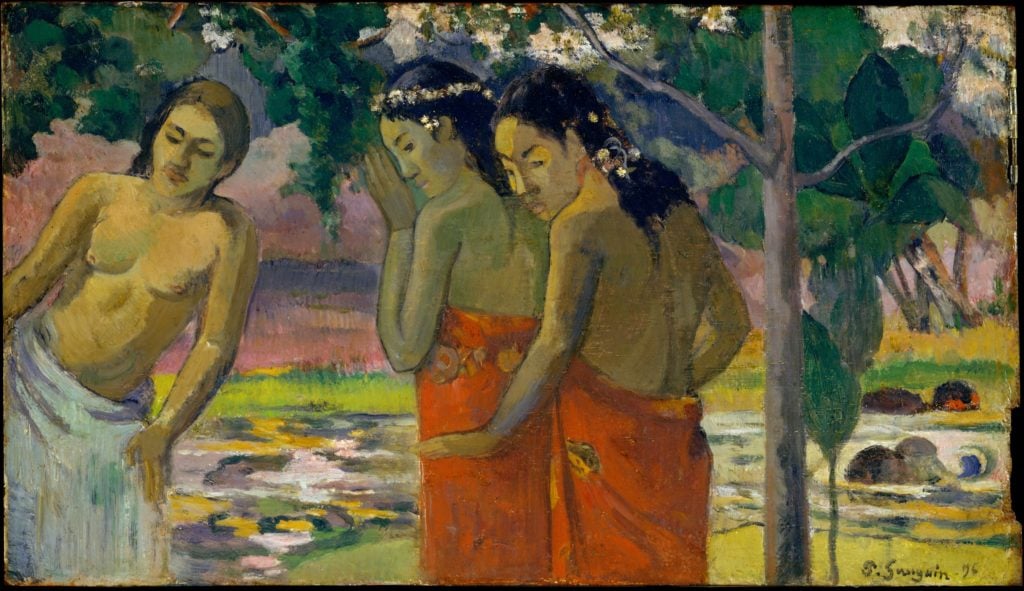

Paul Gauguin’s Three Tahitian Women (1896). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gauguin is another problematic figure in the history of art, known as a consummate womanizer and shameless exoticizer of non-Western culture. The Met has nearly a dozen of his Polynesian paintings, so it certainly wouldn’t miss one of the many similarly titled Three Tahitian Women, Two Tahitian Women, or just simply Two Women. Qatar Museums dropped $300 million on a 1892 portrait of two Tahitian women by the artist in 2015 and, per our records, another painting—also titled, you guessed it, Two Women—went for $21.5 million at Sotheby’s in 2006. We’ll assume the Met’s Two Women could fetch a healthy $70 million today should it catch the eye of another Qatari collector.

Fictional amount raised: $70 million

Any self-respecting museum should have works by Picasso, and the Met has some 537 of them. But the man behind these works was a known misogynist with a history of disrespecting women, once holding a burning cigarette so close to the face of one of his wives that she felt that he might want to brand her. In the Met’s robust collection of his work resides the 1903 painting Erotic Scene (La Douceur), which shows a nude blue-and-ochre woman performing fellatio on the semi-clothed artist. We advocate for its removal not as a gesture of undue censorship, but because even the artist once had the good sense to deny he’d actually made the work, which is ever-so-slightly tawdry in comparison to the rest of the oeuvre. Picasso works regularly break the double digits and the imprimatur lent by the Met can’t be beat, so even though this one is modestly sized and has subject matter not exactly appropriate for mixed company, we estimate it could bring the museum—to use a round number—$20 million.

Fictional amount raised: $20 million

Although it’s tempting (for parallel structure reasons) to say the Met should put up for auction Portrait of a Man (“The Auctioneer”), that work is only by a Rembrandt follower. Instead, one of several true Rembrandts that are not on view, such as Portrait of a Man (c. 1655–60), could be sacrificed for the common good. (It seems reasonable to sacrifice a Rembrandt that is not on view so that millions of tourists can see the better Rembrandts that are on view, no?) Portrait of a Man has some condition issues with the hands, hat, and body, but the face remains beguiling, so it ought to fare well on the market. In 2009, Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo (1658) sold for $33.3 million and Saint James the Greater (1661) sold two years earlier for $25.8 million. Considering how few Rembrandts are in private hands, this one could far exceed expectations, but we will conservatively set the price at $35 million.

Fictional amount raised: $35 million

Kenneth Baker, the San Francisco Chronicle art critic, had it right the first time when he said that Alex Katz was among the most overrated artists. Baker changed his mind, but the Met should follow his original advice and let go of one of its 13 Katz paintings, only one of which is on view. The Met can keep that work, and it should do the same with the iconic portraits of the artist’s wife Ada, but why not sell the 1969 oil on aluminum John’s Loft, which represents the home of poet John Ashbery. Ashbery died last year, so we figure striking while the iron is hot (or cold, as the case may be for Ashbery) should yield a price tag in the higher range of Katz’s recent sales, which can go well into six figures. This one could go for $400,000.

Fictional amount raised: $400,000

Edgar Degas’s Sulking (c. 1870). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

At a time when the #metoo movement has inspired many people to rethink the implications of enjoying art created by monstrous men, it’s high time to rethink Edgar Degas, who broke off his friendship with Jewish artist Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro for anti-Semitic reasons and admitted he equated women with animals. We suggest the Met let go of one of its 217 Degas works, Sulking (c. 1870). It’s not one of his best: It’s dark, the composition doesn’t flow as well as one expects of a Degas painting, and, as the museum notes in its description, “the subject of this picture remains elusive.” It’s been nearly 30 years since Degas’s similarly composed Les blanchisseuses sold for $13.7 million (adjusting for inflation: $29.2 million), and the artist has been selling well of late, so we figure this picture could bring in about $15.5 million.

Fictional amount raised: $15.5 million

In Manhattan, office space goes for a premium, so why doesn’t the Met put some up for sale? Not its actual offices of course (although, now that we mention it, maybe they can consider that too). But the museum could sell off Edward Hopper’s Office in a Small City (1953), currently in storage. It depicts a solitary, solemn figure—a Hopper hallmark—in what is assuredly a gem of a corner unit with two huge windows boasting expansive urban views and ample afternoon sunlight. For those who like Hopper’s illustrative style, this is a handsome picture, but the Met has more than a dozen others it can substitute. Plus, the museum can’t compete with the Whitney as a Hopper destination, so it shouldn’t make a charade of trying. Hopper’s work has fetched sky-high prices in recent years, notably with the 2013 sale of East Wind Over Weehawken (1934) for $40.5 million. (That work, it bears noting, was itself the subject of a very controversial deaccession.) In 2006, another window painting from around the same time, this one set in a hotel lobby, went for $26.8 million, so we’ll estimate the Met could expect around $40 million for its piece of prime Hopper real estate.

Fictional amount raised: $40 million