This is the second interview in a four-part series by Folasade Ologundudu featuring Black artists across generations who work with social practice. You can read part one, an interview with Linda Goode Bryant, here.

Rick Lowe is an authority on art rooted in community participation. “Meditations on Social Sculpture,” his first-ever gallery show in New York and his first since joining Gagosian last year, traces a decades-long multidisciplinary oeuvre that spans the studio and the streets, from Houston’s Third Ward to Los Angeles’s Watts and beyond.

Lowe’s new paintings evolved out of what he calls “social sculpture”: art that is made with and for the community. The most famous example is Project Row Houses (1993–2018), located in one of Houston’s oldest African American neighborhoods. For 25 years, Lowe and his collaborators worked to turn a cluster of abandoned shotgun houses into homes and workspaces for low-income people, young mothers, and artists. During its tenure, Project Row Houses has offered residences, grants, and fellowships for artists and held exhibitions and activities for the people who lived in and around it.

In 2013, Lowe won a MacArthur “genius” grant for his work bridging conceptual theory with practical action, bringing a fresh perspective to problem-solving in divested communities through art-making, political activism, and intersectionality.

A pioneer in the budding genre of social practice art, Lowe has inspired generations of creative contemporaries and emerging artists to think more critically and thoughtfully about the ways in which art can inhabit space, but also have an impact on those in the communities where it is exhibited and housed.

Over several Zoom calls, Lowe shared what led him to seek out creative solutions to real-world problems, how he approaches his own moments of self-doubt, and why he is optimistic about the next generation picking up where he leaves off.

To listen to an audio version of this interview, tune into the Artnet News’s Art Angle podcast.

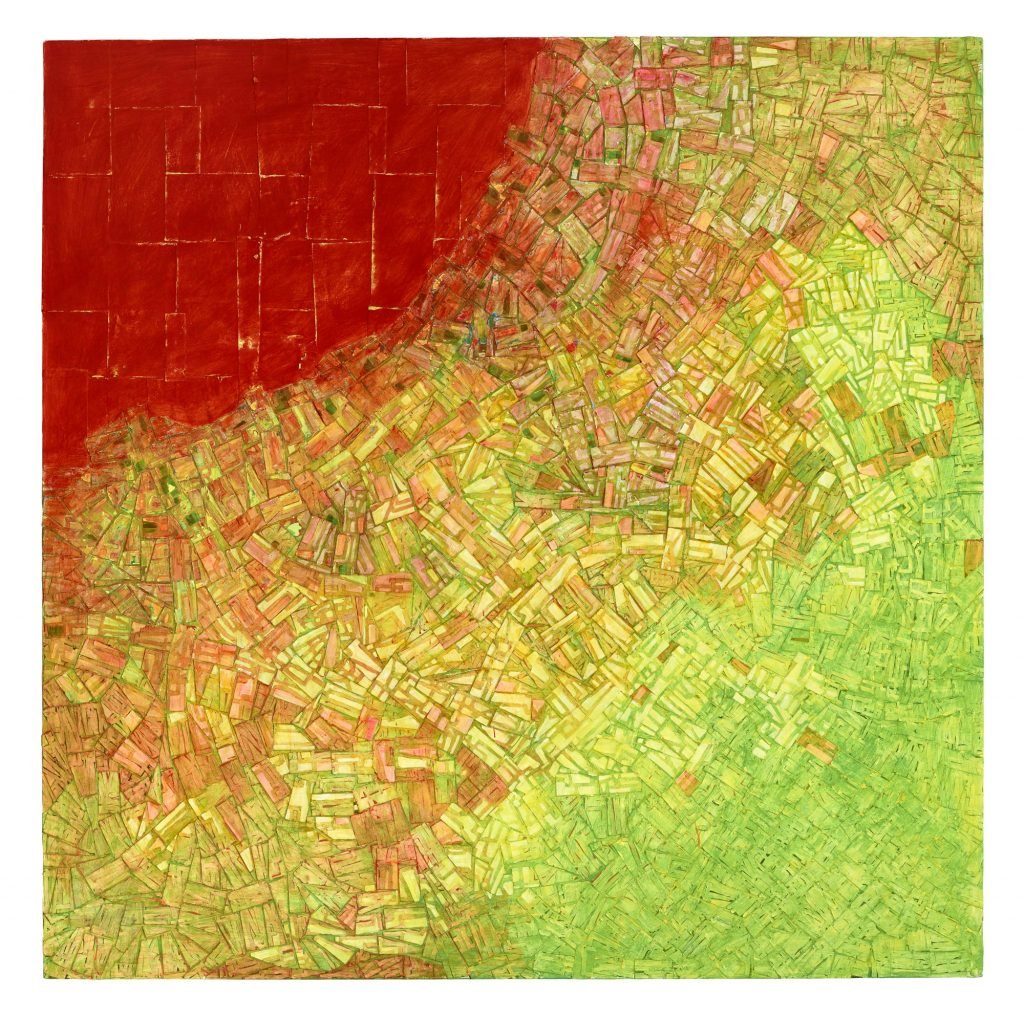

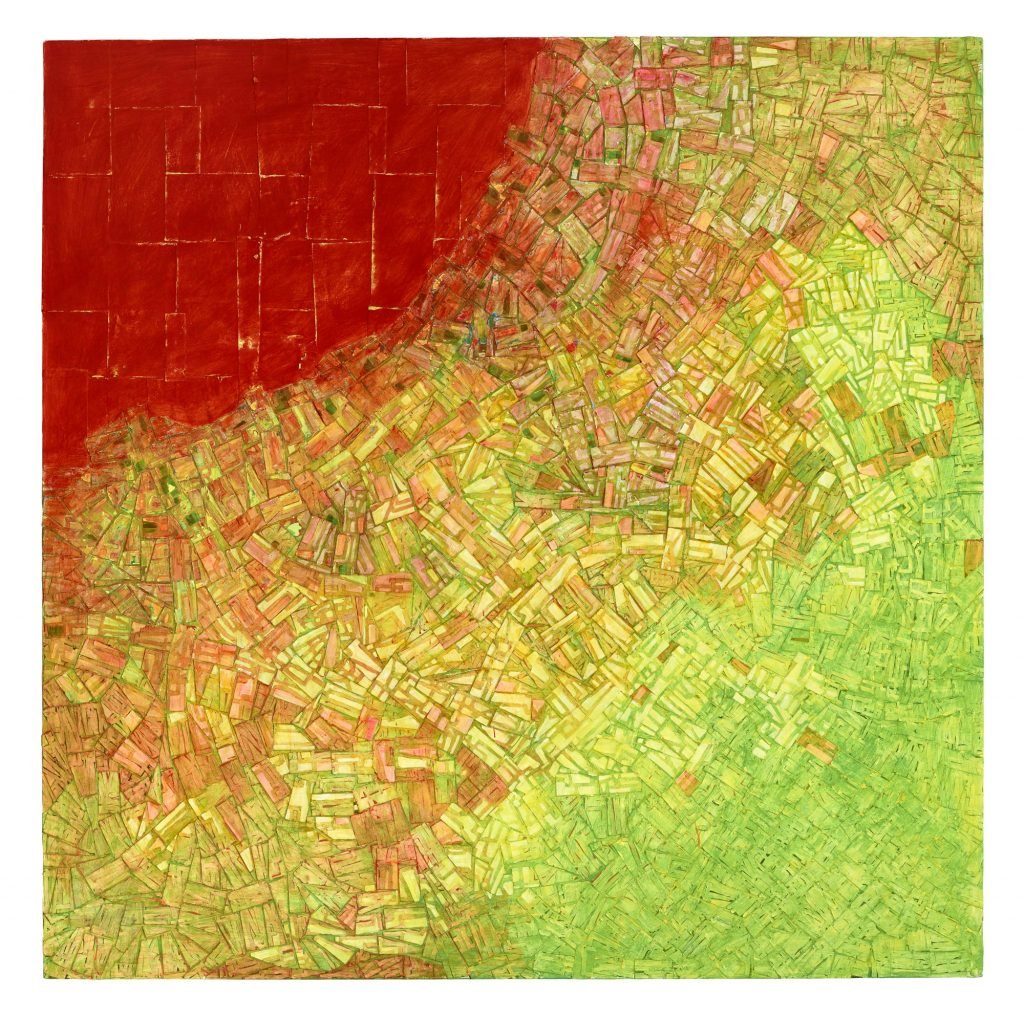

Rick Lowe, Victoria Square Project: Open Borders (2022). © Rick Lowe Studio. Photo: Thomas Dubrock. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

You were born in Alabama, studied painting in Georgia, and, in the ‘80s, moved to Houston, where you lived for many years after attending Texas Southern University. I’m curious to learn more about your origin story in the arts. What are some of the early moments and experiences that led you to pursue an education in art?

There wasn’t really a moment. There were things that might’ve seemed like they would lead that way from early on, but I had no context or understanding of art. I never thought of art as something that I would be connected to. It wasn’t until I went to college and I signed up to take an art class because some of the other basketball players and folks in the sports world where I was, suggested that I take an easy class for the first semester. As my energy and my commitment started shifting away from basketball, it slowly slipped into art. At a certain point, I was so enthusiastic about it.

At that time, in Georgia, what sort of work were you making? Were you in a painting class, a sculpture class?

The first first class I took was a drawing class. After that, my next studio class was three-dimensional design and that was interesting. There were only a handful of students around the art department and I became one of those people that was just around. The head painting teacher suggested I take a class with him and I did. My early painting was mostly landscape painting.

Rick Lowe. Photo: Brent Reaney. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

What made you leave home and decide to move to Texas?

Before Texas, I moved to Biloxi, Mississippi. I was encouraged by one of my professors that I was ready to go out into the world and tackle the world because I wasn’t a very good student. So I went out into the world. I wanted to go someplace where I knew someone. My brother and his wife were stationed there in the Air Force and I stayed with them a little while, and then I got my own studio there. That’s when I first felt like I was beginning to be an artist. By the time I moved to Mississippi, I was making the shift from landscape painting to figurative work. It was very politically driven. I was in Mississippi for about a year and a half and of course I had the idea that I should, like every artist, go to New York. I thought about it and I’m such a country guy, I can’t handle cold weather. I thought about L.A. but then I said, maybe Dallas.

In the early ‘80s, Dallas was a more known city than Houston. A friend of mine was living in New Orleans. We drove from New Orleans to Houston. It was such a weird place, it was desolate. It had a rawness to it that I really could connect to. It felt very Southern in a sense, and almost rural in some of the urban pockets. There were these areas that were just blown out and I decided at that moment, “I’m gonna move to Houston.” So I went back to Mississippi and packed up and moved to Houston.

Project Row Housess in Houston, Texas (Photo by Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

This is a perfect time to talk about Project Row Houses. It’s one of your best known projects in social engagement. What are some of the initial ideas that inspired you to start the program? You’ve done so much with it and it’s had so many lives and so many legs. Artists can come, people in the community can be impacted by the space.

I was doing figurative painting that dealt with political and social issues. I felt I was an activist, so I was making paintings, but the paintings were a part of my activism. A number of my exhibitions at that time were in conjunction with community organizations. I would do exhibitions for international human rights week at the University of Houston. I would do installations about police brutality with local community groups and all that was working fine, I thought, until the infamous moment that I always talk about, when this young kid just pulled the rug out from my whole career up until that time. It was 10 years of work. He just comes in and tells me, “While your work shows what’s happening in our communities, we don’t need that. If artists are creative, why can’t they create solutions?” And I was like, oh my god. That just shattered things for me.

Because up until that point, you had just been making work.

Yes. I was making work that was supposed to be symbolic of things, representative of things that were going on. I took it as a challenge from this young kid. I closed my studio down and I started reading and trying to find other artists that have done things that had a practical application. I ran across a book with Joseph Beuys in it and there was a chapter called social sculpture. He defined it as the way we shape and mold the world. It was interesting to me and I started thinking, how do you make social sculpture?

One day, I was on a tour with a group of activists that were petitioning the city not to tear down buildings all over the neighborhood. On the tour, we passed a block and a half of 22 little shotgun houses. I was intuitively connected with those houses. I was captivated by them. I kept driving by them and I started thinking about John Biggers.

John Biggers was an African American artist who moved to Houston in the late 1940s, started an art department at a local historical black college here, Texas Southern University, and did a lot of paintings with these little shotgun houses in them. I was fascinated by his paintings.

We spoke on a previous call about how there is a great lack of critique around social practice and socially engaged art. How has that affected the movement as a whole?

Most art exists in this world where it has to prove itself over and over to stand the test of time. It has to be able to handle criticism. We have to find ways that we can honestly critique things because everybody wants to be better and critique is a way that you move yourself forward. I just didn’t want the whole notion of social practice being untouchable in terms of critique because that’s not gonna work for it.

Installation view, “Rick Lowe: Meditations on Social Sculpture” 2022. © Rick Lowe Studio. Photo: Tom Powell Imaging. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

Absolutely. In a recent conversation with Thelma Golden and Sir David Adjaye on the eve of curator Antwaun Sargent’s first exhibition of social practice art at Gagosian, Thelma mentioned the idea of mapping in your work. Can you speak more specifically about mapping—the importance of geographical location and the ways in which site-specific work uncovers hidden histories in Black American life?

I’m very fascinated with the idea of physical mapping, but also social mapping, psychological mapping, and all these patterns we make from our daily lives of just repeating things. Most of the time, we’re making patterns that we don’t even recognize, right? We don’t really acknowledge the fact that I’m mapping a source of information. I’ve been doing so over the last nearly 30 years of doing social practice work and trying to understand communities. There’s so many things about the process of life that happen through patterns that are fascinating to me. I get to ask these questions as I make paintings, and in my own head, I make my own answers.

With social practice, you have the visual component of art-making on the one hand and the real-world application of problem solving on the other. In your opinion, how do those two things work together?

That’s a very good question and I think that’s why critique is important, right? What is the relationship between the practical aspects of making art and this whole idea of art creating solutions to problems such as housing shortages. I think that was part of Joseph Beuys’s idea of social sculpture. There was a sense that religion had failed us as a way of organizing society to reach its highest self, and politics had also failed.

All of a sudden, social practice and community engaged art has been scrutinized in this way of, how do you measure it? You can’t measure an artist who’s working on a project about feeding homeless people against an organization that’s tasked to solve world hunger.

The Collard Green Room at Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas. (Photo by Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

Tell me about some of the things you’re working on in your latest exhibition at Gagosian.

Most of my work is untitled. I don’t really work with titles because I don’t necessarily have specific things that I’m trying to illustrate other than my fascination with this notion of patterns and color and how it speaks to us.

I’ve started to think about how painting could be a way of me archiving some of the community-based projects that I’ve been working on over time, because that’s one of the challenges of social practice work—it is ephemeral. Project Row Houses is getting close to 30 years [old], which is great, but most projects don’t make it that far. I’ll have a couple of paintings that are Project Row Houses-related.

Your practice has become critical to our broader understanding of social practice as a movement. Has the movement, if one can call it that, achieved the goals that it initially set out to? Have you achieved the goals you set out to?

This spring, I had my moments where I just thought, does this stuff have any meaning? Does it have any real value? Sometimes, I’ll allow myself to be a little down and I mope about it. One day I was going around in my studio and I pulled something from my archive: a book by a Roman philosopher called The Constellation of Philosophy. It hit me that something in the book was relevant to what I’m feeling now. With social practice, I’ve given so much and I’ve tried to do everything. Sometimes I ask myself, is anything really happening here?

Rick Lowe, Untitled #052922 (2022). © Rick Lowe Studio. Photo: Thomas Dubrock. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

As you look to the future, what are you most excited about in your work and in your life in general?

At this stage, I’m most excited about participating with younger artists and trying to be a part of the energy that they apply to continuing the work that I’ve done. I’m a continuation of other artists’ work. I’m looking at the next generation of people. I think our society has been challenged by our shift away from the notion of social movements. It’s moved into everybody doing their own thing. As a species, we are definitely stronger together, but we’ve been moving apart for the past 40 years or more.

Art can play a big role in bringing people together and helping us find our way back to what I think our nature really is—being social beings. It’s when we are most social that we’re capable of addressing the challenges that we have. I think young people are going to have to fight their way out of the world that they’ve inherited. I’m looking forward to [seeing] how the young folks will teach us or teach themselves. Hopefully I’ll get a chance to see some of that in my lifetime.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.