On View

How One Artist Turned a Wrongful Conviction and a Prison Sentence Into Powerful Performance Art

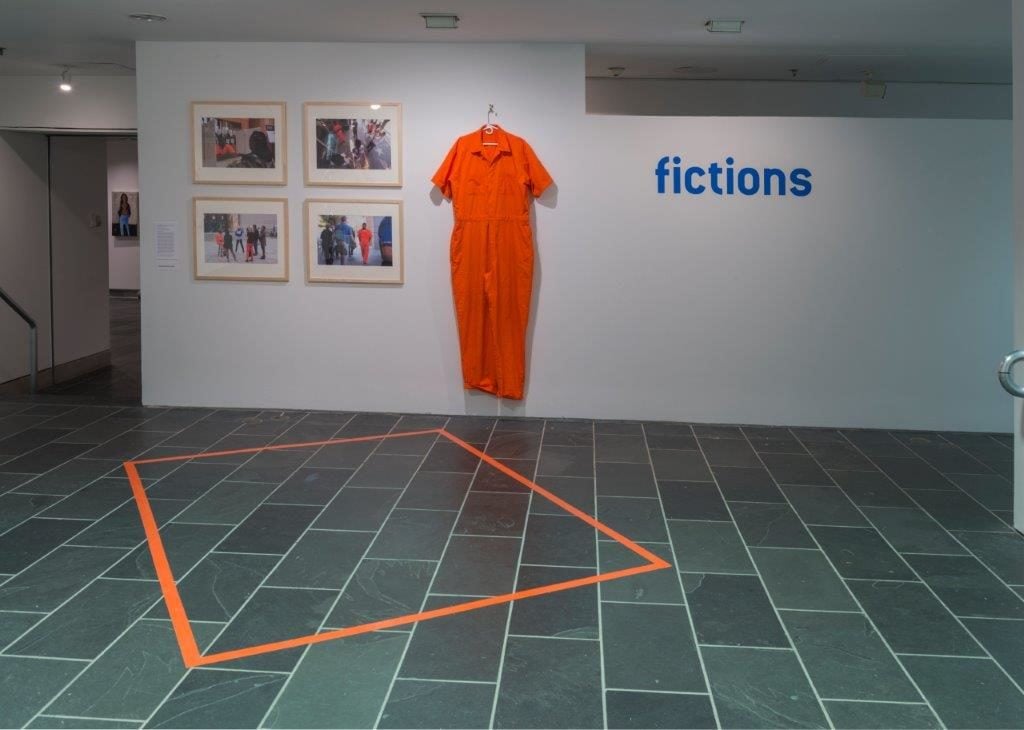

The "Jumpsuit Project" involves a prison-issue outfit and a simulated jail cell.

The "Jumpsuit Project" involves a prison-issue outfit and a simulated jail cell.

Brian Boucher

The ninth of August 2012 started out unremarkable for artist Sherrill Roland, but his life would change forever with a phone call he got that day. A detective reached him as he was preparing for his first year of the MFA program at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, and told him that he faced felony charges in Washington, DC. (The artist declines to name the charges or the identity of his accuser.) Confused and shocked, Roland maintained his innocence. The charges were later downgraded to a misdemeanor, resulting in a two-day trial before a judge, not a jury. Based only on testimony from the two parties and a detective, the judge ruled him guilty, and he was sentenced to a year in prison. Roland would lobby for a retrial in order to clear his name, but before that could even happen, his attorneys turned up exculpatory evidence that the charges were fabricated. He was released and his record was wiped clean—but not before he had spent 10 months and two weeks in prison.

Roland was initially hesitant to discuss his ordeal. But rather than hide the experience, he created a performance art project about it. In The Jumpsuit Project, he dealt with his experience in public, wearing a prison-issue orange jumpsuit whenever he was on campus during his second year of the MFA program to provoke conversation about how people view those whom society has labeled criminal.

Since then, the artist has fielded invitations to stage another iteration of the performance at venues from the Studio Museum in Harlem to Los Angeles’s Otis College of Art and Design, as well as the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. In this version, he lays down orange tape on the floor to approximate a prison cell and discusses his experience with those who step inside.

The project takes place amid a rising national conversation about the ills of mass incarceration and its effects on people of color. Artists like Cameron Rowland and Andrea Fraser address the topic in their work; arts patron Agnes Gund and the Ford Foundation are funding the fight against mass incarceration; and activist lawyers like Michelle Alexander and MacArthur “genius” Bryan Stevenson have authored books on the subject. Roland’s performance not only gives an individual face to the statistics but also calls attention to a part of the American population—numbering over 2 million—who are, by design, out of sight.

Documentation of the performance appears in “Fictions,” on view at the Studio Museum through January 7, 2018, and Roland will give a performance in the lobby on December 10 at 4 p.m.

For this edition of “Origin Story,” which explores the backstories of individual works of art, Roland spoke with artnet News about what he learned in prison, the conversation that sparked the jumpsuit project, and the vital importance of prayer in surviving his traumatic episode.

Sherrill Roland’s installation at the “Fictions” show at the Studio Museum (2017). Courtesy of Studio Museum.

When I came to your performance in Harlem, you specified that you don’t name your accuser or indicate the charges. Why is that?

When I came out and began to speak about my story, my intentions weren’t to say that the other side is terrible, that I hate them, and that you should hate them. It’s about how I transformed and changed through this experience. All this outweighed any personal feelings that I have for the other side.

What kind of work were you doing before this?

For a summer job, I would go home and work at factories in my hometown of Asheville, so during my first year I was working with media like cardboard, wondering if these kinds of production materials, which are worth nothing, could speak to this experience of many people in my community. My professors always asked, “Don’t you have stories to tell? We need more of you in the work,” but all the while, the charges were hanging over my head, and I was trying to hide my fear.

What did you learn while you were in prison?

The human quality was the biggest thing. It was humbling because I thought, “Don’t put me next to these guys. I’m not jail material!” I assumed everyone else was. But these guys were just like me. It was a weird thing to judge somebody but then ask not to be judged. And I learned about forgiveness. We all make mistakes. The system made a mistake about me, but I’m not without fault either.

I was digging, trying to understand, asking God, “Why?” I was working, doing everything good, so why was it all taken away? But there was an older guy, locked up for 20-some years, who said, “I know you’re not in here for what they said you did, but you need to not sleep this experience away. You’ve got to see it differently. There could be a reason why you’re here.”

Mass incarceration and the racial disparities bound up with it have become a major focus in recent years. How did this experience change your perception of the phenomenon?

A guy who was facing life got Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow. We mostly shared everything we had, and everyone who read it, their mind was blown. There was a chapter on statistics about African-American males and incarceration in DC., and suddenly, I could look through the bars and see it for myself. I used to see the numbers but not be a number. That’s when I started thinking about what I was really up against—and not only the person that made the false accusations against me.

I didn’t get into Bryan Stevenson’s book Just Mercy until I went back to school. It was tough for me to even get through the first chapters. I’ve talked to other lawyers like him, who are helping the wrongly convicted, and what I took from that is that there is a serious ripple effect: the trauma affects not only the person wrongly convicted but everyone else around them.

Sherrill Roland’s Jumpsuit Project: UNCG (2016), on campus at University North Carolina Greensboro in 2016. Photo Olivia Bond, courtesy the artist.

So then, after nearly a year of imprisonment, what was it like to head back to school?

After the charges were dismissed, I finally told the whole story to my professors. At that point, I was thinking about a career change. I had no interest in art school or in making things. I sat down with Sheryl Oring, a socially engaged performance artist, in her living room, and told her I wanted to maybe move to Argentina and work on a vineyard. And she was like, “Do you have any other ideas?”

“Well,” I said, “I have this other idea but I’m not sure I should tell you. It’s really stupid.” I told her I was feeling like, what place do I have at school? What does an orange jumpsuit even look like on campus? And she said, “That’s it.”

So how did the project go from her living room to the classroom?

Sheryl introduced me to the campus police, and we set up meetings to make sure I would be safe. They sent a picture of me to the local police with a description of the project. They wanted me to wear a sign that said “school project.” But I said no, I’m not going too far, I’m wearing a backpack and earbuds. I’m not wearing handcuffs, and it doesn’t say “Department of Corrections” on the jumpsuit. I had to figure out what was just enough and not too much. Some people ignored the suit; some ran, like really ran from me until they got out of sight of me, then saw me and ran again.

I set up rules for myself. When I was in the DC. D.O.C., I had to get a hall pass that stated the time I left the block and my destination—chapel or lawyer visit, say—and they would send me back with another one. If I strayed from my route, I would get sent back to the block, privilege vetoed. I echoed that on campus. The art building was my cell block. My studio was my cell. When I’m outside, I can’t stop. I have to immediately go to another facility or building. When spring came, though, I did find longer ways to get from A to B!

You mentioned that prayer helped to get you through. Was that part of your life previously?

It was big in my family, but I didn’t really have it in my life so much. But as soon as I got closer to God in prison, things started turning upward for me.

This is going to sound weird, but have you read Plato’s allegory of the cave? I had this experience in a dark place and I come out changed, so for me, it was a religious experience, but I don’t want to force that on you if you’re not religious.

I’ve been invited to bible study groups to talk about this project, but my presentation isn’t really any different from it in an art setting other than a few words. I still talk about forgiveness and caring for the next person and not judging.

Were there particular passages that were meaningful?

So many! Daniel in the lion’s den, Jonah in the belly of the beast. The one that stuck with me the most was Jeremiah 29:11. Jeremiah had been banished and exiled, and God spoke to him and said, trust in the plans I have for you to prosper. I will give you hope and a future. I will bring you back. That was on my studio wall for the whole year. I don’t believe I’m Jeremiah, but sometimes those words just hold weight. That’s what got me through it.

“Origin Story” is a column in which we examine the backstory of an individual work of art.

“Fictions” is on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, through January 7, 2018; Sherill Roland will present his performance “Jumpsuit Project” in the lobby on December 10 at 4 p.m.