The Burns Halperin Report

The Art World Is Actually Not Very Creative About What It Values. What Would It Take to Change That?

The Burns Halperin Report looks at value in the art world. But there are many other ways to measure it.

The Burns Halperin Report looks at value in the art world. But there are many other ways to measure it.

Charlotte Burns &

Julia Halperin

The art market is a barometer of taste (what is worth buying) and our museums are repositories of cultural memory (what is worth saving). Together, they determine and reinforce values and norms in the mainstream art world.

As the 2022 Burns Halperin Report reveals, there is a profound asymmetry underpinning these systems. And it is easy to slip into a shared delusion about how much progress we are making.

Progress moves like a pendulum, swinging to extremes before settling on a stable arc. Or at least, that’s the dominant narrative within the art world. This misapprehension feeds and fuels the perception of progress—which is believed by many to be so rapid, so outsized, that we are already witnessing a backlash against it (have things gone too far?).

The obdurate reality is that change has barely begun. More work by women entered museum collections in 2009 than any year since. For Black American artists, the peak year was 2015.

The situation is especially acute where racism and sexism intersect. Fewer than 2,000 of the almost 350,000 works we catalogued were by Black American female artists—just 0.5 percent of total museum acquisitions in the 12-year span we examined.

Rather than structural change, the data shows that the art world occasionally venerates a few anointed superstars, but that the underlying value systems remain carefully undisturbed. This is a pattern, with different rhythms, that bears out across the international art market and American museums.

These two systems are connected because the market is now such a dominant force in the art world, and because museums are reliant on private support for their survival. Patrons drive museum acquisitions: 60 percent of the objects in our database entered museum collections by way of gift or bequest.

As museum directors and curators point out to us, this makes it difficult for even the most forward-thinking institutions with the most carefully considered acquisition budgets to move beyond legacy-minded models. They simply cannot outspend their donors.

Given this reality, should museums reconsider their strategies? The volume of work to enter public collections is extraordinary: the 31 institutions we worked with acquired almost 350,000 works between 2008 and 2020. Is this growth sustainable, especially since it so poorly reflects the audiences museums say they serve?

Whose agendas is this supporting, and why? Is there a better funding model or, as our partners at Museums Moving Forward suggest, a way to split finance and governance to better distinguish expertise from spending power?

The situation requires both immediate action and long-term planning. At the current rate of change, it may be a simpler task to build entirely new museums and market structures than to create the necessary change within the existing systems.

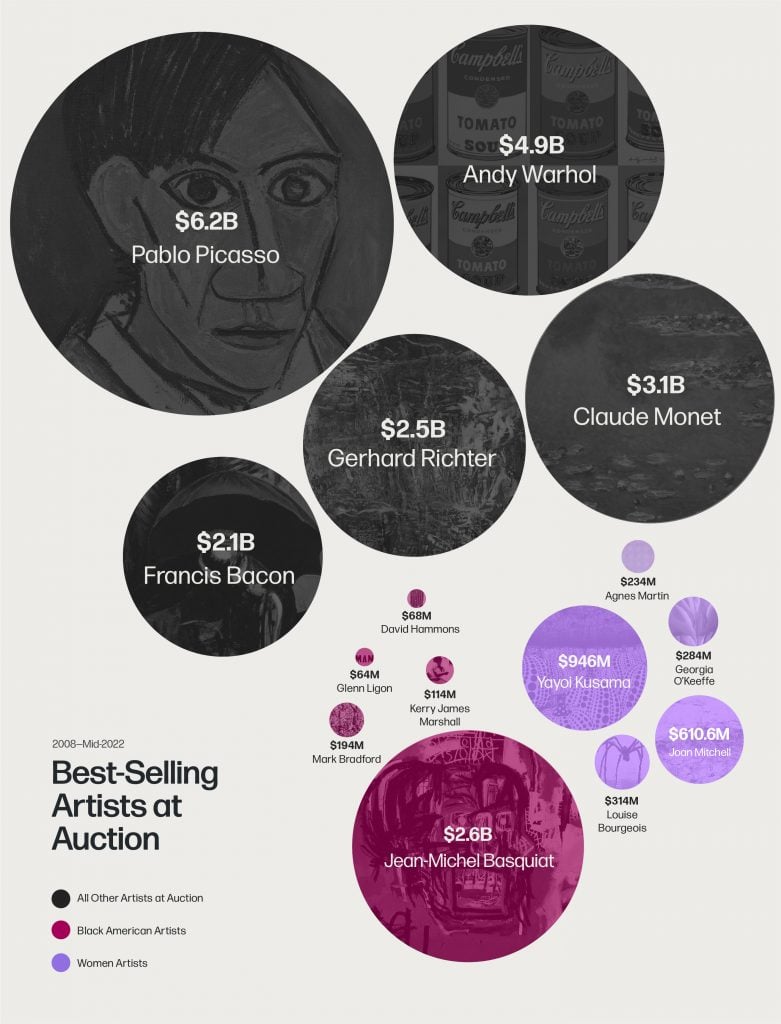

Graphic by Nehema Kariuki. Courtesy of the Burns Halperin Report 2022.

What does it mean that one man is deemed more valuable than every single female artist combined? Sales of work by Pablo Picasso made $30 million more at auction between 2008 and mid-2022 than the sum total for work by all female artists in the same period.

You might make an exception for Picasso. So let’s set aside the genius myth and consider Beeple. Auction sales of his work in just two years comprised half the value of the entire market for all Black American female artists across the past 14 years ($98.9 million vs. $204 million).

These two men are not anomalies, either. Avant-garde or mediocre, white men stand a better chance of success and face fewer barriers to entry in the art world. Despite physically embodying more than half the planet’s population, the combined auction share for Black American artists and all women artists represents just 5 percent of the global market ($9.8 billion of a total $187 billion spent at auction between 2008 and mid-2022). According to our projections, there will not be parity for women artists in the auction market until 2053.

The data shows us that, despite its belief in exceptionalism, the art world is not special. The sexism, racism, and misogynoir that shape our society are evident in these figures.

When asked to estimate our findings, museumgoers sitting outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art on a recent Saturday got much closer than leading dealers, collectors, curators and journalists we spoke to at top art fairs. The art world has drastically overestimated its own pace of progress, often letting even small gains slip quickly away without sustained attention.

“Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room.” Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art/ Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen.

But this lack of specialness is also where we can find ordinary kinds of hope. Like everything else in life, we see the impact and importance of care and focus. The data also shows us the effect of individuals: we can see clearly within institutions the effect of dedicated directors who build careful teams and board support. In her forthcoming op-ed, Jessica Morgan, the director of the Dia Art Foundation, explains how the institution has transformed its collection since she arrived there eight years ago.

We can also see how diversity is good for business—and how underrepresented artists must often overperform to maintain position. Female and Black American artists are better represented in galleries than they are in the auction market or museums, and from the gallery data provided, we see that they clearly out-earn their counterparts in terms of revenue.

We see the effects of thinking in dialogue with regional colleagues—and of shrugging off some of the weight of history. West Coast museums, mostly established decades after their East Coast peers, are solidly ahead when it comes to female artists, for instance.

Contemporary museums are also making significant efforts. Leaders in the field operating above the national average across the three data sets include the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

One of the biggest takeaways is that people, not budgets, create culture. In fact, museums with an annual budget of $15 million to $20 million outperformed their larger peers when it came to acquiring the work of Black American artists.

At the same time, money accelerates change. The collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., shifted in recent years at a scale that impacts the national numbers.

Opening for “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future and R. H. Quaytman: + x, Chapter 34” at the Guggenheim, 2018. Photo: Scott Rudd.

When we tell people these numbers, they gasp. But often the next reaction is to find a reason to excuse or explain them. Some people (though rarely artists, who live this reality) feel like the data is a ruse, because it is so out of step with how they feel about progress.

Like the data, these reactions reflect a paucity of imagination. The problem with data is that it shows us only what has been possible, rather than what might be in the future.

These are not the best systems we can build, nor are they the only paths open to us. We track this data because we believe that it is important to have markers in time of where we are; but we extend an invitation to our colleagues in the field to work with us on improving the ways we think about value in culture, and how we might measure and sustain it.

Institutions should not be reliant on one visionary leader. Markets that recognize value in a broader pool of artists would be richer and more sustainable. Art, and our understanding of value in the truest sense, could be so much more abundant than it is right now.