Art & Exhibitions

Most Know Photographer Dora Maar as Picasso’s Spurned Lover. But a New Exhibition Argues We Got Her Story All Wrong

The Tate Modern show reveals a relentlessly inventive artist.

The Tate Modern show reveals a relentlessly inventive artist.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

For many people, Dora Maar is simply Picasso’s jilted ex-girlfriend, an independent spirit who turned into his clingy “weeping woman.”

But a new show at Tate Modern in London seeks to overcome those preconceptions and place Maar—a photographer with an eye for absurd and erotically-charged images—at the forefront of the Surrealist movement.

Gathering over 250 works, including photographs, photomontages, and printed matter, the survey, which first opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, includes lesser-known works, such as her street photographs of the 1930s and paintings from the 1940s onwards.

Born Henriette Theodora Markovitch in Paris in 1907, Maar grew up in Buenos Aires. On her return to France, she studied painting and dabbled in photography, and her artistic talent was quickly spotted by her teachers. At 23, she reinvented herself as Dora Maar. By 1932, she had established a successful photography studio, where she undertook commercial work in fashion and advertising, shot portraits, and even took nudes for erotic magazines.

The early 1930s were hectic and glamorous years for Maar. One fascinating wall in the exhibition is dedicated to portraits taken of Maar by the likes of Brassaï, Paul Éluard, Cecil Beaton, Irving Penn, and Lee Miller. It was Éluard who first introduced Maar to Picasso in 1935. They met on a film set where she was working as a photographer. (He did not remember the encounter.)

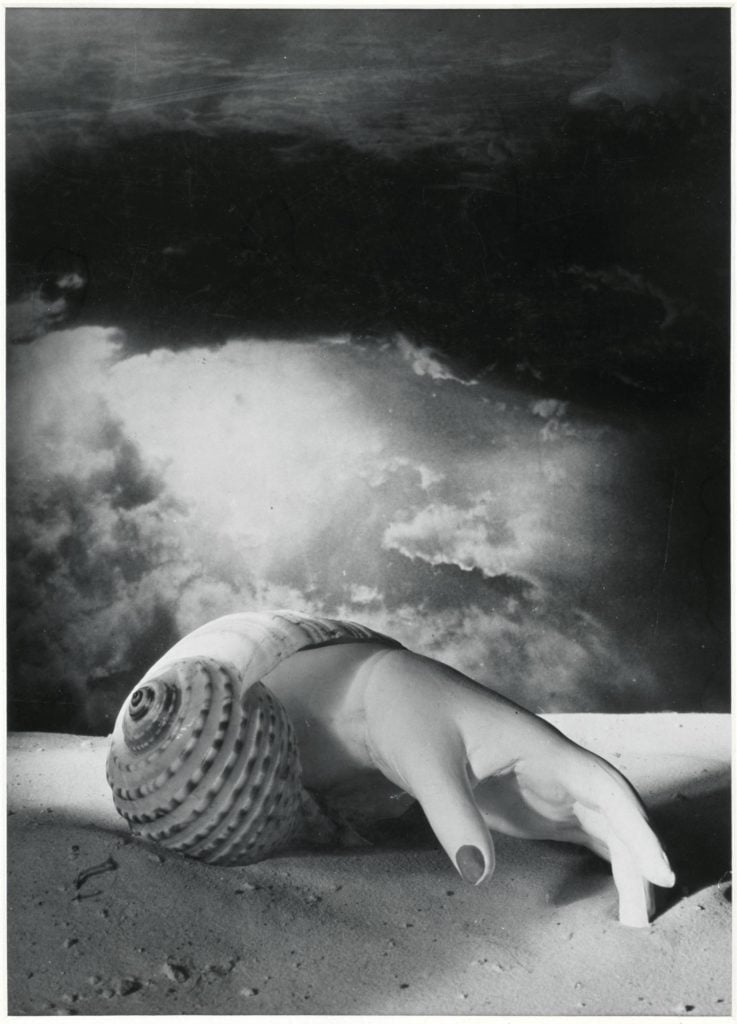

Dora Maar, Untitled (Hand-Shell) (1934). © Centre Pompidou, MNAM CCI, Dist. RMN. Grand Palais/image Centre Pompidou, MNAM -CCI © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

The Tate’s curators have done an excellent job conveying Maar’s creative restlessness and ambition by dividing her early work into four rooms. One is devoted to her commercial assignments; two are focused on her street photography, photojournalism, and cityscapes; and a large room, painted dusty pink, showcases her extraordinary Surrealist output. She zealously pursued all these strands in the same heady period, from the early 1930s up to around 1936.

The standout room of the show is the Surrealist one. Here hang all her best-known photographic masterworks, including The Pretender (1935), where a boy contorts himself backwards while standing on a vaulted ceiling turned upside down. Her Portrait of Ubu (1936) is a disturbing yet tender close-up of a strange, otherworldly creature thought to be a baby armadillo. Untitled (Hand-Shell) (1934) is a disembodied hand, stiff like a mannequin’s, which protrudes from a seashell against a backdrop of apocalyptic clouds.

But the show also provides a chance to discover lesser-known but equally dazzling works, such as the suggestive Untitled (Villa for Sale) (1936), an erotic collage in which a naked woman pulls her long, dark hair upwards while standing on the steps of a derelict house.

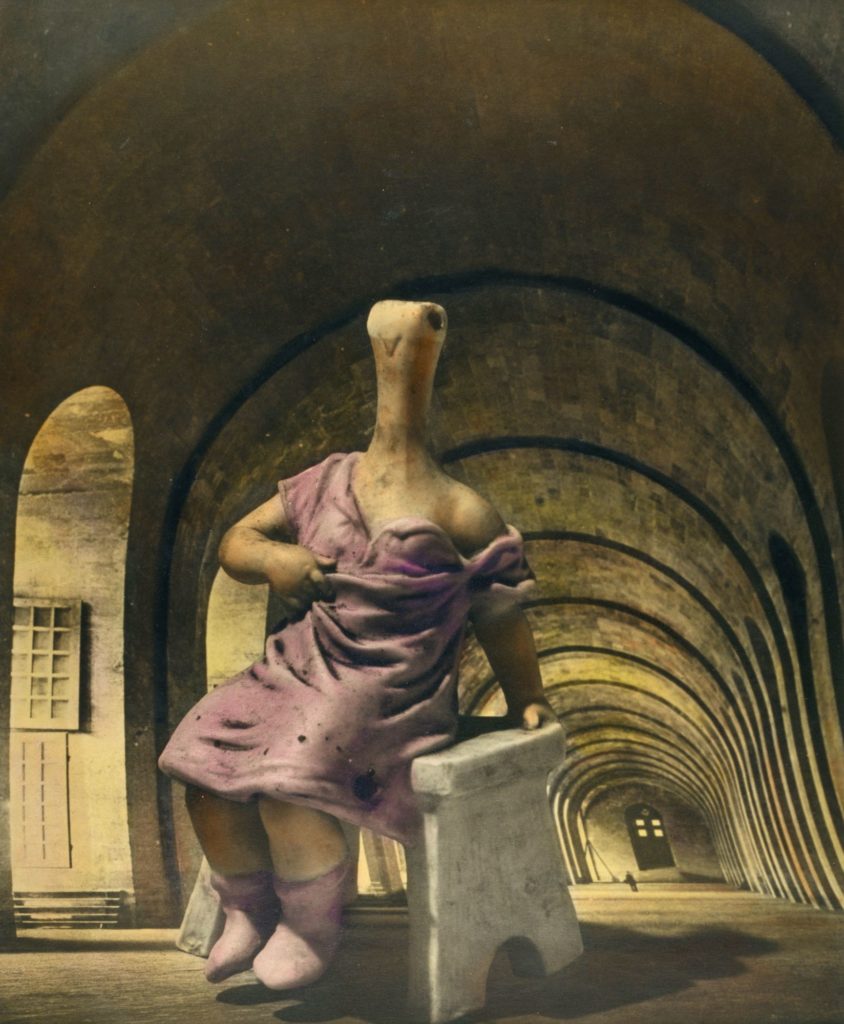

Dora Maar, The Conversation (1937). Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz. Picasso para el Arte, Madrid © FABA Photo: Marc Domage © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019.

The year that bookends Maar’s most creative period as a photographer—1936—is also the one in which her orbit collided with Picasso’s, which brings us to the (Picasso-sized) elephant in the room. The Tate’s curators address this thorny issue in a positive way by focusing on their collaborative endeavors, and how they mutually influenced one another.

On show, for example, are the photographs that Maar took of Picasso painting Guernica in 1937, and we are told of how she urged Picasso to take a more public stance on the Spanish Civil War, which he had previously refused to do. She also taught him the complex technique of cliché verre, which combines photography with printmaking. There are also a few portraits of Maar painted by Picasso, most notably his 1937 Weeping Woman, which is in the Tate’s collection.

Perhaps more problematic is Maar’s abandonment of photography for painting in the late 1930s. Picasso had an ambivalent relationship with photography. (He is quoted as having said: “Inside every photographer is a painter trying to get out.”) One cannot help but wonder how much influence Picasso had on Maar’s decision, and what role his own insecurities may have played. Tate, however, frames Maar’s shift from photography to oil painting as an active choice, a return to her roots as a painter.

Dora Maar, 29 rue d’Astorg (around 1936). Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM. CCI/P. Migeat/Dist. RMN. GP © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

There are two rooms dedicated to Maar’s paintings. The first canvases are painfully obedient to Picasso’s Cubism. She is so resolutely in his shadow that her works seem mere knockoffs. But The Conversation (1937), which has only been publicly exhibited twice before, is truly fascinating. The large canvas depicts Picasso’s mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Maar sitting back-to-back in a red domestic interior. The style is still quite Picasso-like, but here, Maar seems to have found a greater sense of agency, driven perhaps by her growing frustration at having to share her charismatic lover with Walter, the mother of his daughter, Maya. The painting features an electric ceiling lamp, a motif that appears in Picasso’s Guernica—possible proof, we are told, that the stream of influence went two ways.

The rest of the exhibition explores Maar’s later pictorial output, ranging from dull-colored portraits and still lifes in the post-war years, to more vivid abstract works.

We learn that Maar suffered a breakdown after her relationship with Picasso ended for good, and that the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan helped her regain her energy and drive. But her paintings never reach the creative heights that her photography did. Still, the show’s commitment to giving a complete and fair portrayal of her career is commendable, as well as necessary.

There was plenty of life post-Picasso, after all. Maar died at the age of 89. In the 1980s, she returned to the darkroom, and created a series of photograms combining photographic techniques with abstract marks, merging all the techniques that she perfected during a lifetime of art-making. Maar was looking for new creative avenues right until the very end.

“Dora Maar” is on view from November 20, 2019 through March 15, 2020, at Tate Modern in London.