On View

Pipilotti Rist’s New Museum Show Is Absolutely Shameless, in a Good Way

The Swiss artist creates a synthetic Eden.

The Swiss artist creates a synthetic Eden.

Ben Davis

A policewoman makes an appearance in Pipilotti Rist’s Ever Is Over All (1997). Her time onscreen in the four-minute video is just a few seconds. But for me she provides the symbolic key for the entire retrospective of the Swiss artist’s work now at New York’s New Museum, dubbed “Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest.”

Ever Is Over All shows a woman, clad in a flowy blue dress, striding down the street and joyfully clubbing in the windows of cars. It’s one of Rist’s most well-known works, and received an extra charge of pop-culture cachet when, recently, it was alleged that Beyoncé lifted its idea for her Hold Up video.

I leave aside the urgent question of whether anyone owns the motif of a woman taking revenge on parked cars. What’s worth mentioning is the difference between the two: Hold Up’s glam rampage is about righteous destruction; Beyoncé’s onlookers appear shocked or delighted.

The crucial reaction in Rist’s work, on the other hand, is from that policewoman. She passes; she salutes; she seems unconcerned. A video diptych, Ever Is Over All’s slow-mo car-smashing is paired with images of large, dewy flowers, suggesting innocence and serving as emblems of femininity.

That’s the Pipilotti Rist artistic universe, right there: transgression doesn’t exist, or is suspended. The law of this land is feminine, and it is non-judgmental.

Pipilotti Rist, I’m Not the Girl Who Misses Much, 1986 (still).

Sound by Rist after “Happiness Is A Warm Gun” (1968) by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Courtesy the artist, Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York, videoart.ch, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine.

“Pixel Forest” gives you 30 years of the Swiss artist’s experimental and memorable videos, from her scrappy ‘80s works, replete with funky graphics and glitchy effects (shown via quirky hood-like viewing stations that protrude from the wall); oddball video sculptures like Massachusetts Chandelier (2010), a hanging light fixture made of a membrane of dangling undies; to, most memorably, her spectacularly absorptive recent video environments.

Detail of Pilipotti Rist, Massachusetts Chandelier (2010). Image: Ben Davis.

Rist (b. 1962) was raised in what has been described as an “upper-middle-class churchgoing family.” She played in a band, Les Reines Prochaines, and was inspired by artists with an unexpected take on the body, like Bruce Nauman, Yoko Ono, and VALIE EXPORT. The great theme of her unconventionally feminist work has been living free of shame.

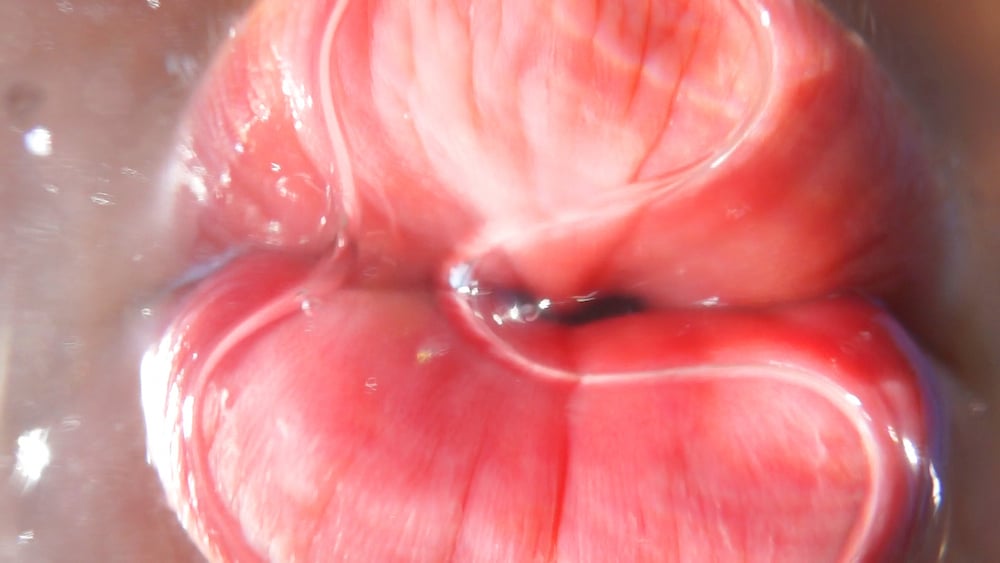

Aside from Ever Is Over All, the other key early work for me in “Pixel Forest” might be Pickelporno (1992), a response to the then-raging ‘90s debates about feminism and pornography. “I thought that we should have used all that energy to say what we like,” the artist tells the New Museum’s artistic director, Massimiliano Gioni, in the show’s catalogue, “and so I decided to make a porn film for women or a porn film I would like.”

A man and a woman approach each other across a grated floor. In close-up, you see the woman very carefully balance her high heels to avoid getting them caught; the man, in flat shoes, has no such problem—a suggestion of how male and female experience can differ, how that which supports one might be very uncomfortable for the other.

Then the couple confronts each other and the film dissolves into a fluid frenzy of flesh. The camera wheels around bodies, so close that the lips, limbs, nipples, body hair, orifices, and genitals are almost indecipherable, intercut with images of fruit, plants, ice floes, and gushing water, as if their lovemaking was truly cosmic.

Pickelporno was an attempt to make film represent a tactile rather than a visual sensuality. The “male gaze” wasn’t so much critiqued as rendered irrelevant, a parallel imagery of desire imagined, much the way that the policewoman in Ever Is Over All imagined a parallel type of authority.

Ever Is Over All and Pickelporno are actually significant in “Pixel Forest” as exceptions. They represent Rist’s take on violence and sex, respectively—between the two of them, the motor of almost all narrative cinema. Elsewhere such dramas are for the most part bracketed out entirely to achieve Rist’s signature mood, a kind of candy-colored fugue state. In that sense, her work is somehow at once sensual and ascetic.

Consider Sip My Ocean (1996), another two-channel video (the first she ever sold, to Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art). The soundtrack is a watery cover of the Chris Isaak ballad Wicked Game—one of the great Doing It songs—covered in a scratchy little-girl voice, joined by another voice, shouting the refrain “I don’t want to fall in love!” in the distant background, giving the tune a new kind of playfulness but definitely killing the mood.

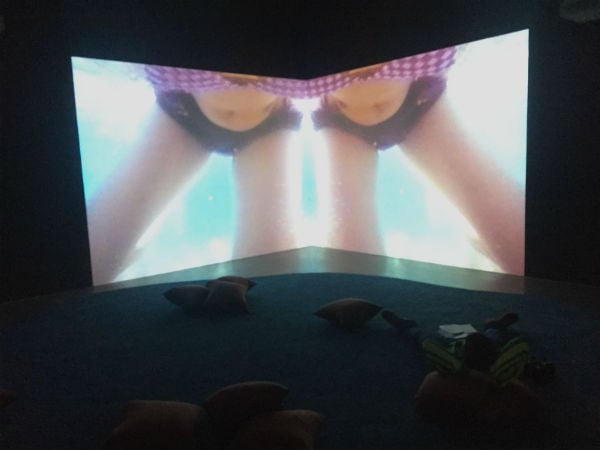

Installation view of Pipilotti Rist’s Sip My Ocean at the New Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

On camera, you see the artist swimming, intercut with images of the sea floor, anemones and other ocean flora pulsing in the current. Her body is presented again from odd angles and in fragments, suggesting an unself-conscious, but definitely non-prurient, intimacy.

The camera also captures, in succession, a toy trailer, a cheese grater, a tea cup, and a toy heart drifting to the ocean floor—the burdening paraphernalia of life, falling away.

By the time you ascend to the latest, most lavish work on view at the New Museum, burdens have all but vanished entirely, and a sense of blissed-out suspended animation reigns. That fact is suggested by even the names of the installations that dominate floors three and four: Mercy Garden (2014), Worry Will Vanish Horizon (2014), and the new-for-the-New Museum 4th Floor to Mildness (2016).

![Pipilotti Rist, <i>4th Floor To Mildness</i> (2016). Music and text by Soap&Skin/Anja Plaschg. Courtesy Flora Musikverlag and [PIAS] Recordings. photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio, courtesy New Museum.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2016/10/pipilotti-rist-new-museum-4th-floor-1024x767.png)

Pipilotti Rist, 4th Floor To Mildness (2016). Music and text by Soap&Skin/Anja Plaschg. Courtesy Flora Musikverlag and [PIAS] Recordings. photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio, courtesy New Museum.

A lot of talk in museum circles centers on “activating the viewer” with interactive work. Rist goes the opposite way. This is video art before which you are meant to de-activate.

A key aspect of all Rist’s installations is the sounds—forest noises, ocean noises, heartbeats, various drones, shimmery aural textures. These resemble the settings on a white noise machine. That says something about the hypnagogic state Rist is trying to achieve, though what she presents is a master craftswoman’s version.

Pipilotti Rist, Worry Will Vanish Horizon (2014). Sound by Anders Guggisberg. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine.

Likewise with her imagery: lots of liquid environments, dewy plants, and only the very occasional hint of anything man-made—a hand lingering along a string of barbed wire—to remind you of the hard corners of the real world. There are naked bodies, again, but again never presented whole—just fragments fading into and out of the shimmering environments. Worry Will Vanish Horizon even features computer imagery that takes you inside the body, set against its nature imagery.

Pipilotti Rist, Mercy Garden (2014). Sound by Heinz Rohrer. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine.

Literary theory offers the following thought experiment: Imagine that you arrive at the “happily ever after” part of a story, where the bad guy has been defeated and true love found. Now extend the plot for 500 more pages. The result would be tedium. The depressing conclusion is that narrative happiness is desirable only as long as it is in doubt, that angst is the partner of interest.

Rist solves this dilemma by rewinding the tape of both mythical and psychological narratives to before they begin. Nature imagery dominates because her perspective is Edenic, before the Fall, before shame and the knowledge of good and evil. Her imagery is womb-like, not just because it is aqueous, but because it stages a world before the clear line between self and environment is established.

If you are the kind of critic who thinks that video art should serve as a foil to the mass media, as a kind of media criticism, then the narcotic pleasures of Rist’s art provoke suspicion. Here is how the artist responds to the charge: “I’m not afraid of the idea that art can heal,” she tells Gioni, adding, “Like with a homeopathic remedy, for you to heal, you need the same thing that makes you crazy.”

The world bombards people with endless, hectoring images. Rist’s video environments ape in miniature this sense of being immersed in perpetually moving images, but it does so specifically to make you stay awhile instead of anxiously surfing on.

Somewhere outside the frame of these videos there’s the real world, where the law is very real and very forbidding, where the body is fragile and endlessly objectified, where nature and humanity are not in harmony but in despairing and desperate conflict. The very care with which these things are edited out indicates a keen awareness of them.

“I’m working to be hopeful about the state of everything,” Rist admitted to the New York Times recently. As in, it’s work—hope doesn’t come easily. It takes a tremendous amount of imaginative effort to create a credible fantasy of tranquility today. It takes giving up a lot to imagine a world so full.

“Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest” is on view at the New Museum through January 15, 2017.