Art & Exhibitions

How MoMA Chose Which Treasures to Send to Paris for Its Biggest Loan Show Ever

The works headed to the Vuitton Foundation were hand-picked by Glenn Lowry and Quentin Bajac.

The works headed to the Vuitton Foundation were hand-picked by Glenn Lowry and Quentin Bajac.

Claudia Barbieri Childs

It is an exhibition of unprecedented scale—and it is unlikely ever to happen again. For five months starting October 11, a blockbuster show of major works from New York’s Museum of Modern Art will go on display at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris. The two institutions released new details about the highly anticipated collaboration at a press conference in Paris yesterday.

“This is absolutely unique,” MoMA’s director Glenn Lowry said. “It’s the first time we have loaned so many pieces at the same time.”

Être Moderne: Le MoMA à Paris brings together 200 works—many iconic, others lesser-known—drawn from all six departments of the New York museum. Chosen to illustrate both the collection’s eclectic spirit and its evolution over time, the works will take up all three floors of the foundation’s Frank Gehry-designed museum in the Bois de Boulogne until March 5.

Roy Lichtenstein’s Drowning Girl (1963). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Philip Johnson Fund (by exchange) and gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bagley Wright, 1971. © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein New York. Adagp, Paris 2017.

The roster of artists reads like a who’s who of Modern and contemporary art: Beckmann and Beuys; Calder, Cézanne, and de Chirico; Duchamp and Dalí; Klimt, Kirchner, Kusama; Matisse, Mies van der Rohe, and Mondrian; Picabia and Picasso; Cindy Sherman and Frank Stella; Wall and Warhol. And that’s not even the entire list.

The motivating force behind the exhibition is MoMA’s ongoing renovation and expansion, which involves a radical reconfiguration of the existing galleries and the addition of a new wing. The project is due to be complete in 2019.

“Without this extension program, it would have been impossible for us to loan six tons of artwork, because we use them at home and our own audience would have been pretty angry if they weren’t there,” Lowry said.

Paul Cézanne’s The Bather (c. 1885). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection, 1934.

This is not the first time MoMA has twinned building work with outreach. “During our extension in 2004, we did loan pieces to Berlin,” Lowry noted. But in terms of scale and significance, the show at the Vuitton Foundation “is without equal,” he said.

The chosen objects range from 19th century post-Impressionist paintings to contemporary digital works. Cézanne’s Bather (1885) will rub metaphorical shoulders with Roman Ondak’s conceptual performance Measuring the Universe (2007), which invites visitors to mark one another’s name and height on a white wall. Art historical stalwarts like Paul Signac’s 1890 portrait of Félix Fénéon and Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse (1906) will be shown alongside Shigetaka Kurita’s 176 emojis, designed in 1998 for the Japanese telecom firm NTT Docomo.

Chosen primarily by Lowry and Quentin Bajac, the show’s lead curator and MoMA’s chief curator of photography, the works span painting, sculpture, photography, cinema, graphic arts, architecture, and industrial design. A representative from the Louis Vuitton Foundation declined to specify the amount MoMA would be paid in exchange for the loan.

Shigetaka Kurita’s NTT DOCOMO, Inc., Tokyo Emoji (1998-1999). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of NTT DOCOMO, Inc., 2016. © 2017 NTT DOCOMO.

The selection process was guided by two principal aims, according to Suzanne Pagé, the Vuitton Foundation’s artistic director. First, the curators wanted to illustrate the multi-disciplinary character of MoMA’s collection—its attention to media beyond painting was revolutionary when the museum started out in 1929. Second, they wanted to show how the collection evolved through donations, acquisitions, and occasional de-acquisitions to remain current in an increasingly complex and diffuse contemporary art world.

The collection is “like a torpedo moving through time, metabolic and self-renewing,” said Lowry, borrowing a simile favored by MoMA’s first director Alfred Barr.

There is, however, at least one prized work that will not come to Paris: Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). “It’s a piece that our trustees decided not to transport,” Lowry said. “They decided this 20 or 30 years ago. Transport is risky; they decided it will never travel again.”

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #21 (1978). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Horace W. Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel, 1995. © 2017 Cindy Sherman.

The installation itself is designed to mirror a philosophical shift at MoMA away from a chronological, hierarchical view of art history and toward a more experimental, lateral approach that is more interdisciplinary and international, Pagé and Lowry said.

While MoMA was the driving force behind the selection of the works, the original impetus for the show came from the French side. The foundation hoped to build on longstanding links between the two institutions, says Jean-Paul Claverie, art adviser to the foundation’s president and LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault.

“As long ago as 2007, LVMH was the single patron of MoMA’s Richard Serra retrospective,” Claverie said. “There is nothing opportunistic about this exhibition. We have a shared complicity with MoMA, as two private institutions, based on private patronage.”

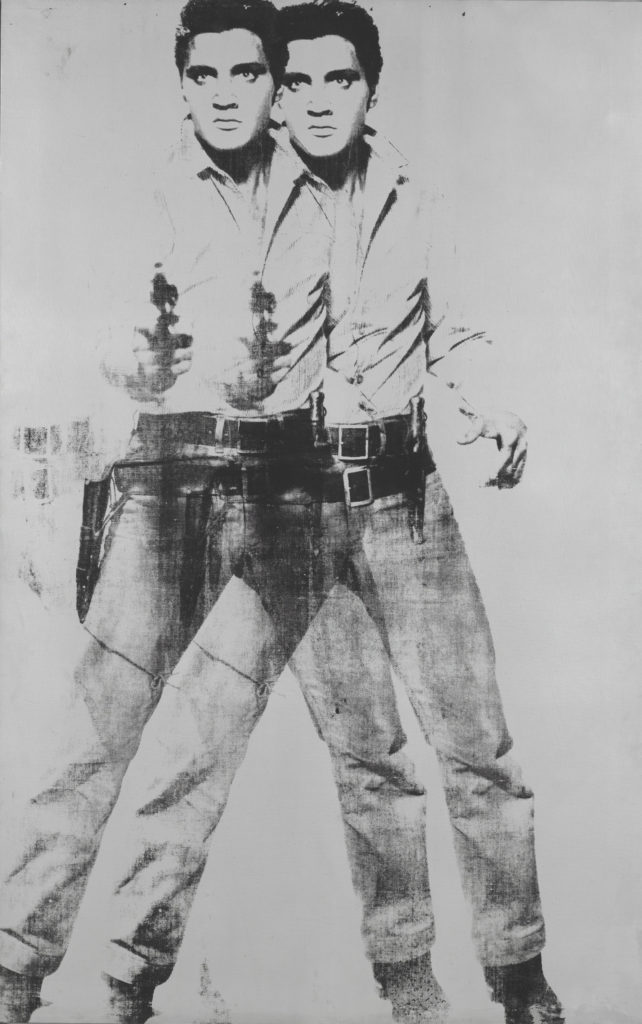

Andy Warhol’s Double Elvis (1963). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Jerry and Emily Spiegel Family Foundation in honor of Kirk Varnedoe, 2001. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Adagp, Paris 2017.

“Exhibition Being Modern: MoMA in Paris” at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris runs from October 11 to March 5, 2018.