Auctions

Who Won Auction Week? Here Are 15 Key Takeaways From New York’s Eyebrow-Singeing $2 Billion Spring Art Sales

From the most expensive work to the biggest flop, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

From the most expensive work to the biggest flop, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

Tim Schneider &

Eileen Kinsella

An eye-watering $2 billion worth of art was bought and sold in New York last week. Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips stuffed 10 sales of Impressionist, Modern, and contemporary art into five jam-packed days. The haul across all three houses was $2 billion, up $100 million from the equivalent sales in May 2018, which made $1.9 billion.

What should market-watchers take away from the onslaught? Here are some parting observations.

Now that the dust has settled from a marathon week of sales, who came out on top? That award goes to Christie’s—yet again. The auction house generated a stunning $1.07 billion (yes, billion) in art sales last week, up from $959.6 million last May.

The other Big Two houses, Sotheby’s and Phillips, both experienced a drop from last year’s equivalent sales. Sotheby’s sold $842.3 million across its evening and day sales, down 16 percent from last year’s admittedly lofty total of $858.6 million. Phillips also brought in less than it did last spring: $134.6 million, down 13.5 percent from the $155.6 million it generated last May.

Notably, these figures all represent gross totals and don’t factor in any financing deals, third-party guarantees, or other arrangements that auction houses often use to secure high-profile material and that sometimes dip into their profit margins.

It was something of an upheaval in the upper reaches of the art market when the highest price of the week came not for a postwar or contemporary blockbuster—think sky-high prices for Warhol, Rothko, and Francis Bacon—but instead for Impressionist icon Claude Monet’s luminous painting of haystacks in the French countryside near his home at Giverny. It sold for $110 million at Sotheby’s, far higher than the week’s next best-selling Impressionist lot, a Paul Cézanne still life, which sold for $59.3 million at Christie’s.

What made this Monet so special? For one, it was relatively fresh to the market, having been held in the same private collection since it was previously auctioned more than 30 years ago, in 1986, when it sold for $2.5 million. According to Sotheby’s: “The present oil is the most evocative and glorious example from the most famed group of pictures in the 19th-century western canon.”

So, who is the buyer? Soon after the sale, the art-market newsletter the Canvas singled out Hasso Plattner, the German software billionaire who opened the Barberini Museum in Potsdam in 2017 and plans to open a new museum in Berlin to house his East German art collection.

William Bouguereau, La jeunesse de bacchus (1884). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The term “biggest” can be taken both literally and figuratively here. Besides Meules, this nearly 11-by-20-foot canvas straight from the heirs of French Academic painter William Bouguereau carried the highest estimate ($25 million to $35 million) and the most house-generated fanfare in Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale on Tuesday. The consignors were confident enough in the market to offer the work without the safety of a financial guarantee or third-party irrevocable bid.

That dice-roll came up snake-eyes, as bidding plateaued at just $18 million before auctioneer Harry Dalmeny finally muttered “pass” and moved on to the next work.

If one auction house knows how to turn the sale of a trophy into a marketing event, it’s Christie’s. And they did not disappoint when it came to promoting Jeff Koons’s Rabbit, which went on to fetch a record $91.1 million last week, dethroning David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) as the most expensive work by a living artist to sell at auction. (Robert Mnuchin, the father of the current US Treasury Secretary, made the final bid on behalf of a client rumored to be Steve Cohen.) The work also had the added luster of coming from the collection of late publishing magnate, S.I. Newhouse, who bought it directly from Gagosian for $1 million, a price that seems quaint in retrospect.

The hype campaign included a Times Square digital billboard as well as a homepage takeover and full-page ad in the New York Times that juxtaposed quotes about the piece from prominent critics ranging from “vacuous” and “crass” to “glamorous.” The tagline underneath it all: “Own the Controversy.” (Social media users were invited to join the conversation using the hashtags #goodbunny and #badbunny.) On the facade of Christie’s Rockefeller Center headquarters, a light installation played with the good and bad press even more: neon letters spelled out the word “ICON” with the “I” flashing on and off. Inside, the real bunny was placed on view in a pristine, custom-built circular gallery. That’s one fancy cage.

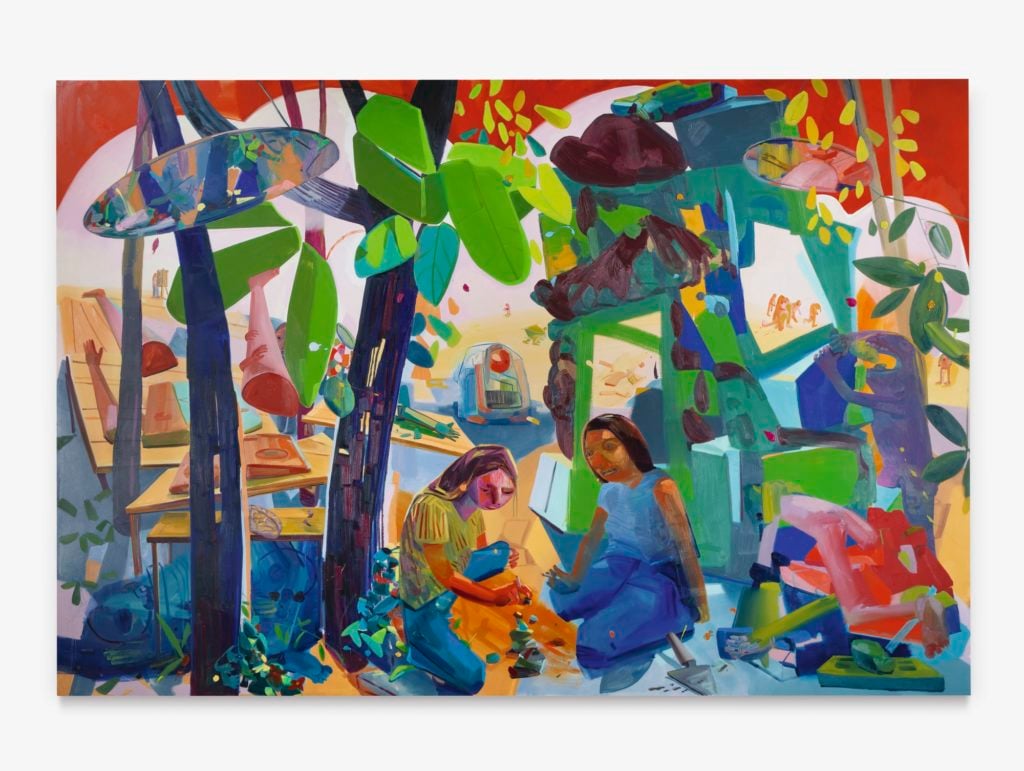

Dana Schutz, Civil Planning, 2004. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

If there was ever an Open Casket hangover in Dana Schutz’s market, Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale proved that it has cleared. Schutz’s Civil Planning, a huge, boldly colored painting from the estate of management consultant David Teiger, briefly transformed the intensity level among the crowd from “friendly tennis match” to “last-jug-of-water-after-the-apocalypse pandemonium.”

With frantic gesticulations volleying in bids of wildly different value from seemingly every corner of the salesroom, even perpetually unflappable auctioneer Oliver Barker momentarily looked overwhelmed by the response. Soon enough, though, he restored order—and brought down the hammer at $2 million, five times the high estimate. (The price rose to $2.4 million with premium.)

This marked the second time that evening that Schutz’s auction record had broken—the artist’s Signing (2009) eclipsed its $350,000 high estimate to bring in $980,000 with premium at Phillips around 90 minutes earlier.

Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale in New York in May 2018. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Financial instruments have been a hot topic for years among art-market wonks, especially since the classic pre-sale guarantee (in which the house agrees to pay the consignor a set price regardless of bidding in the room) mutated into alternate breeds such as “irrevocable bids” (in which third parties back a work for a financing fee and/or a slice of the potential upside) and “enhanced hammers” (in which consignors receive a cut of the buyer’s premium). But May 2019 saw some noteworthy advances in how auction houses and deep-pocketed players wield these tools—or don’t.

True to Sotheby’s CEO Tad Smith’s expression of increased confidence in the market during the house’s latest earnings call, Sotheby’s did indeed use fewer guarantees and irrevocable bids than in last spring’s sales. For example, only nine of the 56 works (16 percent) in Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening sales included one or both instruments this spring, versus 15 of 46 (about 33 percent) in its equivalent sale last May. And this example is representative of the wider auction market: According to ArtTactic, guarantees covered about 39 percent of the Big Three houses’ expected pre-sale value last week—a significant drop from the same cycle last May, when guarantees covered 56 percent of the spread.

But this retrenchment is not necessarily pervasive from sale to sale and house to house. For instance, Phillips guaranteed 28 of the 45 lots (62 percent) in its 20th century and contemporary art evening sale. Fifteen of those guaranteed works hailed from the collection of Miles and Shirley Fiterman, which Phillips won by making the kind of all-inclusive guarantee we normally only see from Sotheby’s and Christie’s—a notable development in itself. And with Kelly Crow of the Wall Street Journal reporting that the number of third-party guarantors has ballooned from about a dozen in 2014 to over 90 today, warping both the fee structure and underlying strategy of backing a work in the process, this spring is just the latest turn in a path that will only get more winding as it continues.

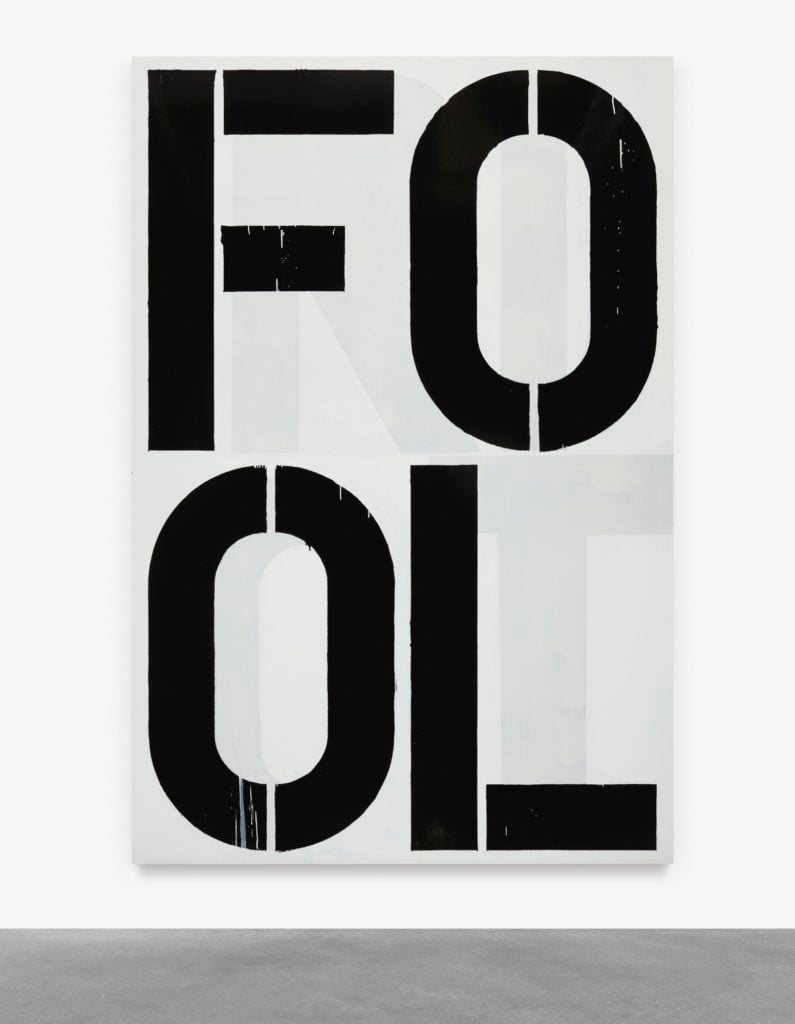

Christopher Wool, Untitled, 1990. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Feeling déjà vu when you look at this work? It’s not in your head. Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale marked the third time since February 2012 that Wool’s Untitled word painting, reading “FOOL” in his now-signature black stenciling, has mounted the block since February 2012. It brought $7.7 million with premium at Christie’s London in its first appearance, then nearly $14.2 million at Christie’s New York in November 2014.

However, the next four and a half years weren’t especially kind to its valuation. Untitled sold for an even $14 million last Thursday—about $165,000 less than in its last go-round.

David Hockney, Pool and Pink Pole, 1984. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The top lot in Sotheby’s contemporary day sale wasn’t just the auction’s most in-demand by price. The small but vibrant oil on canvas, which brought just over $3.1 million with premium, didn’t even get to hang around—literally—until the end of the sale before its winner took possession. Instead, one of the house’s art handlers sauntered in and snatched the piece off the wall in the middle of the action… despite the fact that it was installed directly behind the auctioneer in the salesroom with the plan to stay there for the duration of the sale.

Still, when you consider that the Hockney was just the sixth work offered in a 356-lot sale that ultimately stretched beyond the eight-hour mark, maybe its new owner’s impatience is understandable.

KAWS, Kurf (Hot Dog), 2008. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Every auction cycle gives us examples of highly similar works that are judged significantly differently in dollars and sense, and this May’s was no different thanks to KAWS (the nom de street of artist Brian Donnelly). Two paintings from his Kurf series, centered on the artist’s X’d-eye reinterpretations of characters from the Smurfs cartoon series, mounted the block at Christie’s and Sotheby’s respective contemporary evening sales. However, Kurf (Tangle), the larger of the two paintings at 72 x 96 inches, carried an estimate of $600,000 to $800,000 at Christie’s. The next night, Sotheby’s offered Kurf (Hot Dog), measuring only 68 x 68 inches, with around twice as high an estimate: $1.5 million to $2 million.

The market found the same level in each case, as the works sold for nearly identical prices of $2.66 million after premium.

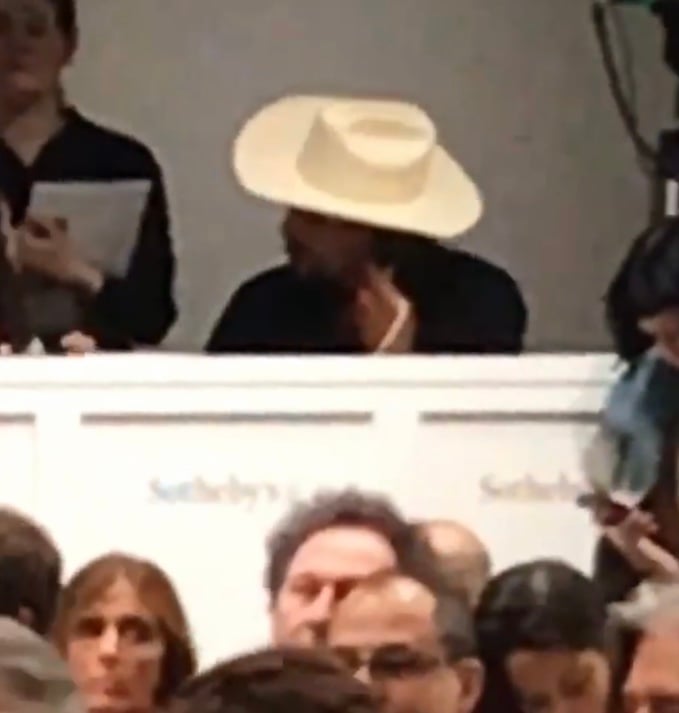

Sotheby’s e-commerce administrator Corey Robinson at the house’s May 2019 contemporary evening sale in New York. Photo by Tim Schneider.

Look, if you think auction-house salesrooms are generally bastions of bold style (excluding overly conspicuous plastic surgery, that is), you desperately need to expand your worldview. But Corey Robinson, an administrator in Sotheby’s e-commerce department, disrupted the stuffy norm at the house’s contemporary evening sale last Thursday when he posted up at the phone bank in an ecru cowboy hat—a much more fashion-forward look than the average bidder in the room probably thought. However, a house spokesperson could not confirm by press time whether Robinson had his horses in the back, or whether their horse tack was attached.

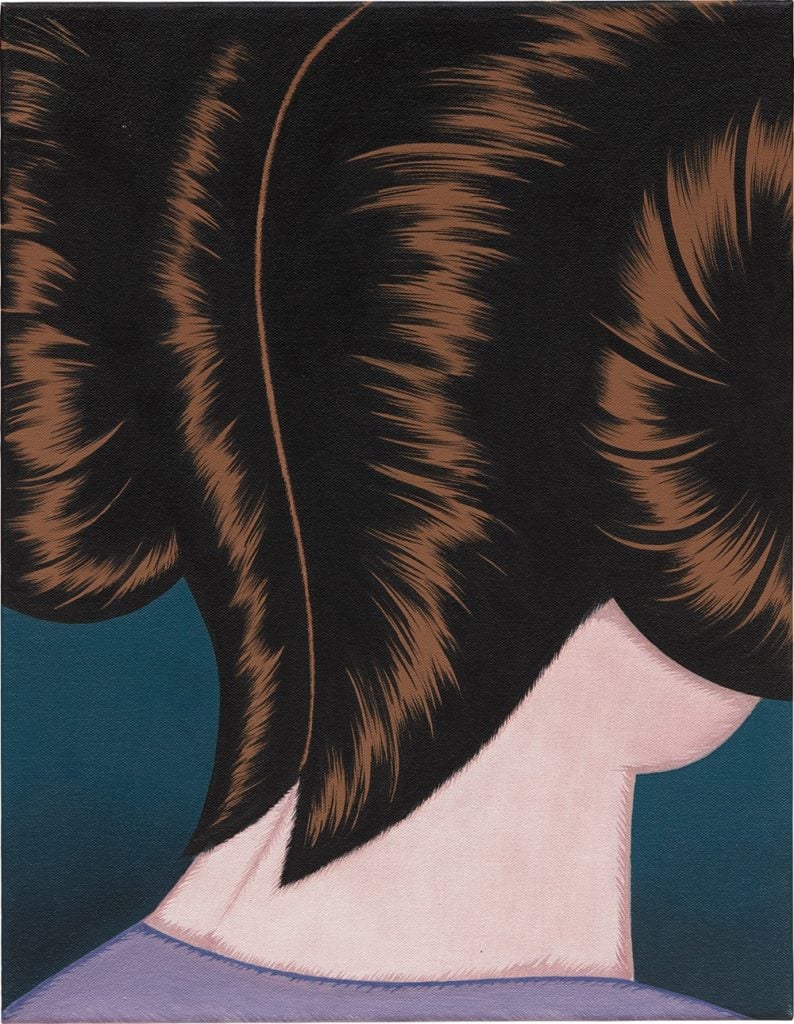

Julie Curtiss, Princess (2016). Image courtesy of Phillips.

A small work by Curtiss, a painter whose first solo exhibition at Anton Kern in New York debuted on April 25, also appeared at auction for the first time in Phillips’s 20th century and contemporary day sale. Princess (2016), the 14-by-18-inch canvas, carried an approachable estimate of $6,000 to $8,000. It was carried out of the auction room at a final price of $106,250. That’s a leap of more than 1,300 percent over its high estimate. We’ve seen this movie before, but for Curtiss’s sake, we hope it ends as one of the best-case scenarios.

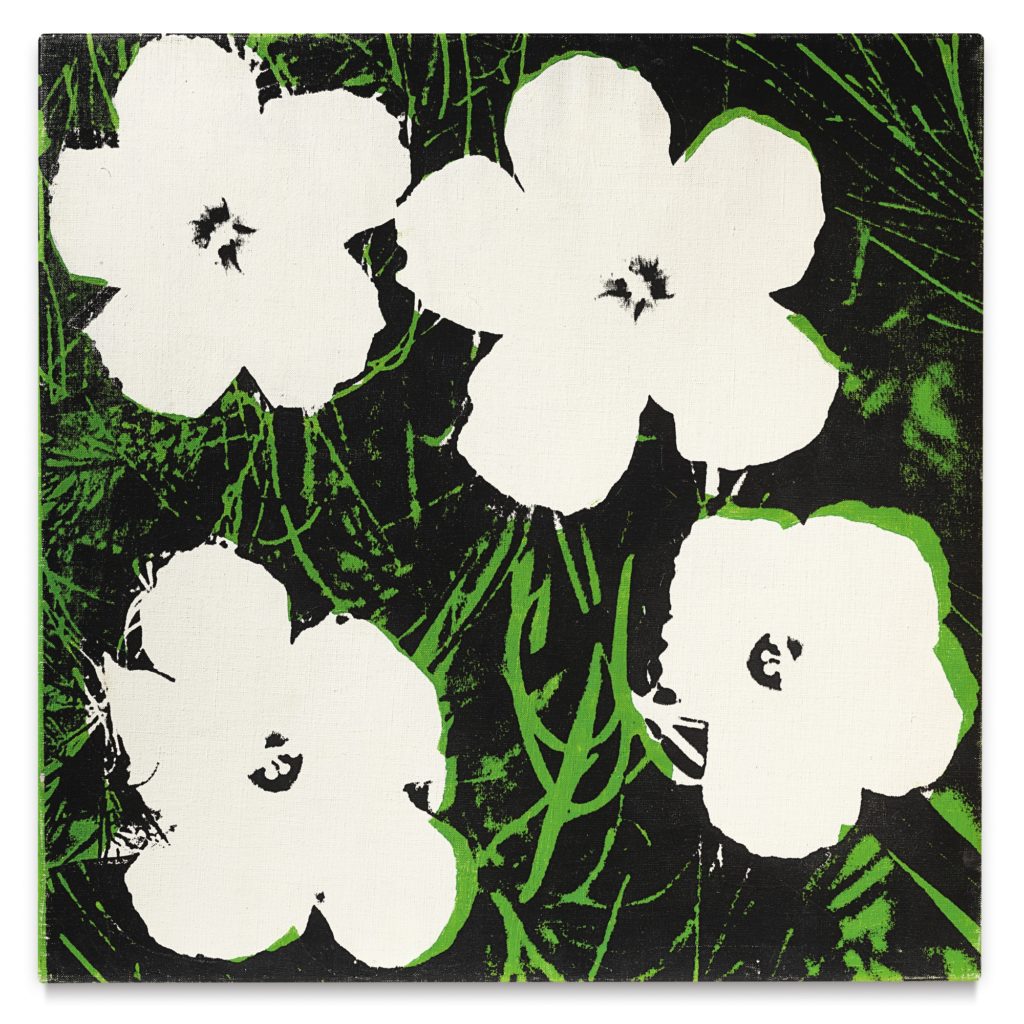

Andy Warhol, Flowers, 1964. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Warhol’s Flower canvases seem to be ubiquitous at auction—55 have appeared on the block since May 1, 2014—so it was a bit confusing when roughly five and a half minutes of bidding propelled this example to a hammer price of $4.75 million, more than triple its $1.5 million low estimate.

But size matters. The majority of the Flower works appearing at auction measure five-inches square or eight-inches square, a fact which casual (or overly busy) observers may not realize when frantically flipping through catalogues or scrolling through online listings. In comparison, this example was colossal (and rare) at 24 x 24 inches.

Still, even among other Flowers of its size, the result was an exception. Before last Thursday, the most expensive work in the series at this scale auctioned in the last five years—blue flowers, if you were wondering—hammered for only $3.6 million at Sotheby’s sale of the Morton and Barbara Mandel collection last May.

For years, Robert Rauschenberg’s auction performance seemed to be out of sync with his towering reputation as a 20th-century master who bridged Abstract Expressionism with Pop art. While peers like Cy Twombly, Mark Rothko, and Francis Bacon have routinely commanded prices upwards of $30 million in the global art market boom, Rauschenberg’s work never rose above $20 million until this season (though prices have in fact exceeded that level privately).

The problem? A lack of supply. That changed when the prestigious collection of Chicago-based philanthropists Robert and Beatrice Mayer came on the block, including Buffalo II, a seminal Rauschenberg work from the early 1960s with striking color and imagery, including then-Senator John F. Kennedy, Coca-Cola, and a bald eagle. Estimated at a minimum of $50 million, it soared far higher, until a one-to-one bidding war pushed the final price to $88.8 million, nearly five times the artist’s previous auction record of $18.6 million set three years ago. Sources told artnet News that Christie’s experts have had their eye on this work for nearly a decade, knowing its rarity and importance.

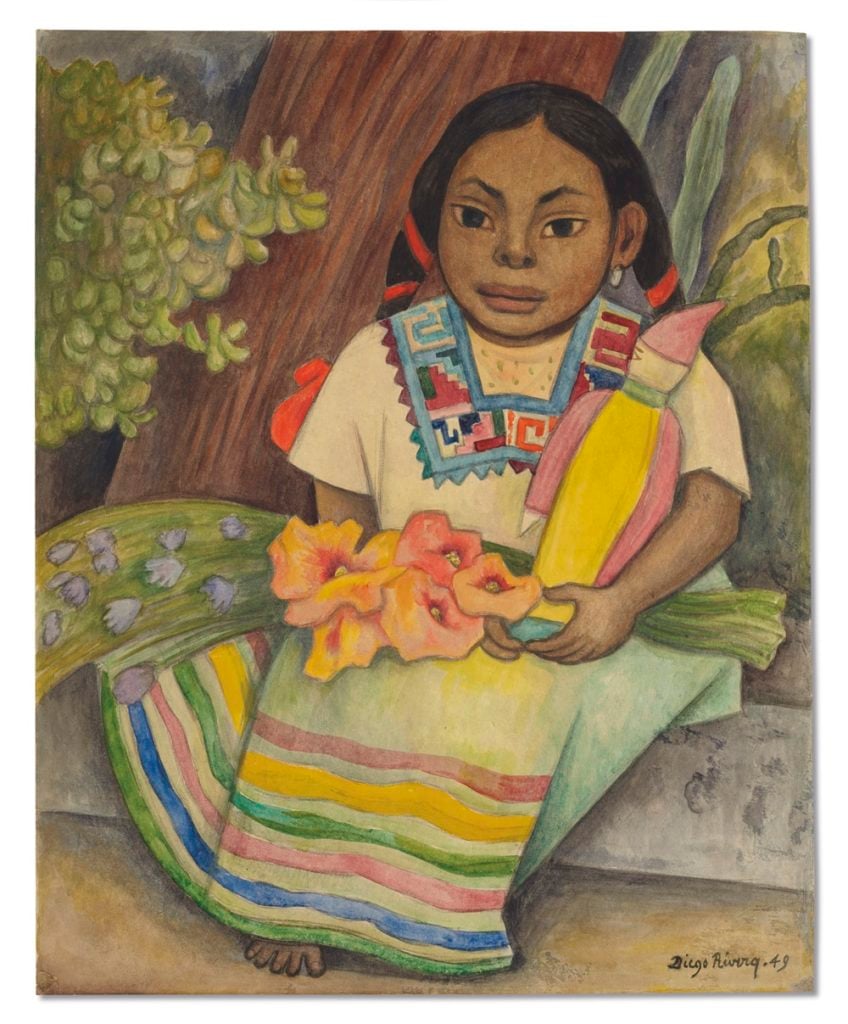

Diego Rivera, Niña sentada con flores (1949). Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Market wisdom has it that the longer a good work has been off the market, the higher price it will fetch once it reappears. So which work in last week’s bevy of sales was held the longest by its owners? According to our estimates, that award goes to Diego Rivera’s Niña sentada con flores (1949), which was purchased by Chicago-based collectors Beatrice and Robert Mayer directly from the artist the year it was made. It remained in their collection for a whopping 70 years before it was sold at Christie’s for $375,000, above its high estimate of $250,000.

KAWS’s Seeing (2018). Image courtesy of Phillips.

Which work sold last week made the fastest trip from the studio to the auction block? It appears to be a tie between a sculpture by market darling KAWS and a painting by artist George Cohen (who, to be entirely honest, we’ve never heard of before).

KAWS’s seated figure inspired by Sesame Street‘s Grover made a pretty penny for its consignor. The work was made just last year as part of an edition of 250, priced at $12,000 each. At Phillips evening sale, it carried an estimate $10,000 to $15,000—and ended up selling for more than quadruple that at $62,500.

Another recently executed work was Cohen’s Two Circles and Three Squares, an acrylic on canvas also created in 2018. It sold for the same price as the KAWS ($62,500) on higher expectations of $30,000 to $50,000.

It should be noted that a number of even more recently executed works were included in the sales, including two completed this spring, but they were intentionally created for auction as part of sales to benefit Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum (at Sotheby’s) and Artadia (at Phillips). The former sale set a new record for Charles Gaines with his mixed media Numbers and Trees: Central Park Series IV: Tree #6, Carmichael (2019), which fetched $475,000.

Another 2019 work for the Hammer, an untitled painting by Laura Owens, sold for $1.1. million, also an artist record. Meanwhile, the final lot at Christie’s evening contemporary sale was a recently completed Jonas Wood painting, Japanese Garden (2019), that was sold to benefit the Global Wildlife Conservation. It was estimated to sell for $500,000 to $700,000 but shattered expectations when it soared to a final premium-inclusive price, and a new artist auction record, of $4.9 million.