Ghanaian artist Cornelius Annor wants to make his father and namesake proud. Cornelius Annor, Sr. was a well-known sculptor within his native Ghana, but he was never able to see his work shown outside of Accra. His son’s career, on the other hand, has had a decidedly different trajectory.

Annor recently opened his second solo show, “A Fabric of Time and Family,” at New York’s Venus Over Manhattan (open until April 22). For anyone newly discovering the artist, the show’s title carries something of a clue to his work and place in the contemporary art market.

Annor is among a group of Ghanaian artists whose expressive paintings of Black figuration have taken the market by storm over the past five years. Others include Gideon Appah, Kwesi Botchway, Otis Quaicoe, Emmanuel Taku, Amoako Boafo, and Issaq Ismail.

Notably, all began their careers either on the roster or in the residency of Accra’s Gallery 1957, and most went to Ghanatta College of Art and Design, which closed in 2015. All have incurred a bit of speculation drama in the market. And their distinct aesthetics have enraptured the world—kicking Black figuration into heavy rotation and moving the conversation about African contemporary art beyond geopolitical borders.

But what happens when two very different art ecosystems collide? Annor offers an example of how artists and international market players are thinking sustainably amid a frenzy for Ghanaian painting.”

Boafo’s staccato, finger-painted portraits first ignited the market furor for African figuration and the shady and territorial conflict it incurred (here’s a refresher). “I don’t know exactly what I have to do to stop them from selling works at auction,” Boafo said at the time.

His auction median is $425,000, and his record is $3.4 million for the painting Hands Up (2018), which sold at Christie’s Hong Kong in December 2021.

Speculation and flipping hit this group of artists hard between 2019 and 2021—and, in truth, it’s probably why you know their names and why they’ve been covered in the media so heavily. As Laurent Mercier of Maurani Mercier, the Belgian outfit that represents Annor, Taku, and Botchway, said: “What was happening was attracting the wrong collectors who are not collectors. They’re asset managers.”

Mercier said the gallery’s first show with Taku outside of Ghana in 2021 saw “inquiries of 500 people per painting. I mean, we couldn’t handle the email traffic.”

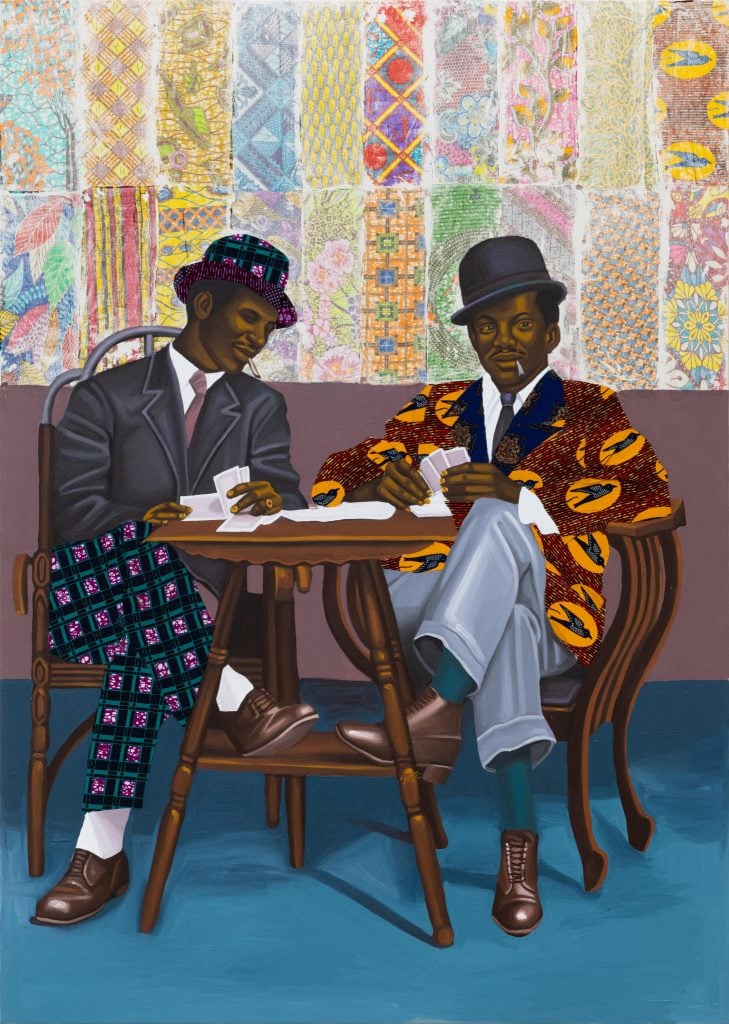

Cornelius Annor, Card players, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and MARUANI MERCIER Gallery

But now, across the industry, Mercier said, “We know who the flippers are,” in part, he added, because the gallery’s been in operation for 28 years.

Marwan Zakhem, the founder of Gallery 1957, said that he too knows who he’s selling to. “We sold over 800 works in the last three or four years, something like that. We’ve only had four works go into auction.”

Venus Over Manhattan said it has cut speculators off, and in fact, is now seeing institutions interested in the work (Mercier confirmed that the Brooklyn Museum just acquired a piece by Annor).

That being said, “speculation works both ways,” said Zakhem. “Speculation is why a lot of these artists have very successful careers.”

Now, in 2023, Boafo still leads the Ghanaian group in terms of prices achieved at auction and in the primary market. His first showing at Gagosian’s Madison Avenue space opened on the same night as Annor’s exhibition at Venus Over Manhattan.

A source close to Boafo told Artnet News that the works currently on view at Gagosian sold for “max $450,000. He didn’t want to raise them too high.”

Meanwhile, a representative for Gagosian would not disclose pricing, however, they did confirm that the show had sold out before its opening on March 16.

Appah, Botchway, Quaicoe, and Annor are no slouches in the market either. Works in Annor’s show at Venus Over Manhattan are priced between $30,000 and $70,000, and his pieces can fetch up to $110,000 in private sales. While Appah, who currently has an exhibition at Pace London, hovers around $80,000 to $100,000. His Boy with a Spear (2020-22) sold for $90,000 at Frieze London, for example.

Botchway’s works now can run between $120,000 and $150,000 on the primary market. In Emmanuel Taku’s show last month at Maurani Mercier, his works were going for between €38,000 and €55,000 ($41,000-$60,000). As Mercier said, “I could sell a Taku at €150,000 ($164,000). I can do that. But how many? I’m not here for the short term. We want to represent artists for the long run.”

With these sorts of numbers, it makes sense that international blue-chip galleries are circling—and raising prices. Appah went to Pace, Annor was added to Venus Over Manhattan, Quaicoe joined Almine Rech, and Boafo just began showing at Gagosian. At the same time, art advisors, collectors, and drama-watchers sent scores of emails and WhatsApp messages to discuss the roster-hopping. In fact, when one of these artists signed with a blue-chip dealer, it was reported that Gallery 1957 learned about it from a press release. It seemed as though the drama was ignited again.

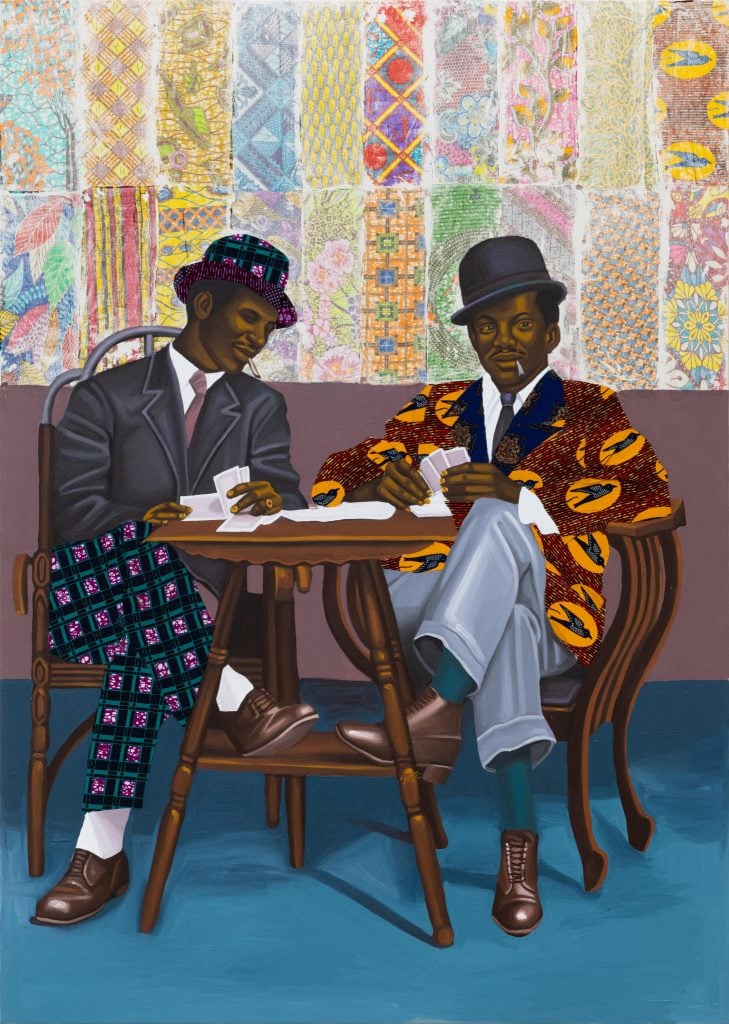

Cornelius Annor, W) ta shi – we have taken our sit, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and MARUANI MERCIER Gallery

I like to see my artist go into good galleries,” said Zakhem, who co-represents many of his artists with galleries based in the U.S., U.K., Europe, or the Middle East, including Venus Over Manhattan, Pace, Mitchell-Innes and Nash, Maurani Mercier, and Efie.

“Within all industries, whether it’s finance, construction, hospitality or the art world, there are going to be people who are hurt, that are going to lose,” he said. “I’ve learned [from] people like Amoako, who will look at me and say, ‘So what? So this guy made $500,000 out of me. You know what, I moved on.’ These guys have figured it out way before we have or the press has or everybody has. They understand what the bigger picture is.”

These days, it seems the art world is reading what is happening in the Ghanaian market in two ways. One take is that blue-chip Western galleries are exploiting these artists and funneling them into a factory model, where canvases are churned out for a competitive supply chain and prices are hiked up so that 400 percent returns can be achieved at auction. In this view, the galleries that helped usher in their success may have been cut out of the picture unfairly.

Conversely, there is the view that these artists are opening up Western art history and correcting the ills of an exclusionary system to include under-represented perspectives (still framed with an eye toward the West).

But there’s also a more novel view, that these artists have figured out how to play the global art market game, building wealth for themselves, their community, and Ghana—without government funding or an organizing body. And most importantly, with their cultural values intact. “That’s what should be the story,” said Zakhem.

They’ve done so by banding together and creating a movement. “They are very generous, so they want to give back to their community,” said Mercier. “What we’ve had over the last five years is the explosion of talent, the explosion of a community that has arisen from this success, and [are] paying back and paving the way for the other hundreds of artists,” Zakhem added.

“This is a moment that they have to grab. And everybody has to coexist in order to make this a really, truly lasting advantage for everybody. And these artists have been doing that,” said Zakhem. “And luckily, Gallery 1957 has been playing a part.”

After all, Ghana doesn’t have a dedicated art museum or many art exhibition spaces. It’s essential for its artists to build in and across Ghana, “where they ply their trade, where they get their inspiration, where they have their family, their friends, and everything around them,” as Zakhem put it.

Many of these artists are investing in Ghana by creating infrastructure and opportunities for young artists and art workers. Boafo was the first to create a residency. Botchway soon followed, with WorldFaze Art Studio, and now Annor’s C.Annor Studio is “a space dedicated to encouraging and supporting young artists.” Even famed palanquin artist Paa Joe is raising funds for his and his son Jacob Tetteh-Apong’s Art Academy. All are training younger artists just as they were mentored themselves.

“We realized that the art market is not only about galleries,” Annor said. “It’s about the world. We need to get our ways out there to be more recognized. That is what is happening.”

“It’s a great family,” Annor said of his artist circle. “We have a broad art community in that group.” In fact, they’re all on a group WhatsApp chat, said artist Yaw Owusu, who is represented by Gallery 1957 and Efie Gallery in Dubai.

Owusu was Zakhem’s first scout when he opened the gallery in 2016, despite the fact that he went to Kumasi Tech instead of Ghanatta, and that he makes sculptural compositions out of the devalued Ghanaian Pesewa coin instead of portraits.

Boafo tried to coax Owusu to come to New York for his Gagosian show (Owusu is currently the artist in residence at Alma Lewis in Pittsburgh). “Everybody knows almost what is happening for everybody,” Owusu said. “And people show up when they can. There is a community where we are celebrating each other.”

This circle, this movement—as Annor’s exhibition title says—is being run the Ghanaian way: all in the family.

“A Fabric of Time and Family,” Venus Over Manhattan, 55 Great Jones Street, New York, until April 22, 2023.