The Gray Market

Donald Trump Is Leading the News Again. Get Ready to See Him All Over the Art World Again, Too

Our columnist fears that what's powering Trump back to the top of the news cycle will also power his image back into the art market.

Our columnist fears that what's powering Trump back to the top of the news cycle will also power his image back into the art market.

Tim Schneider

Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, bracing for an unpleasant repeat…

As has often been the case in the history of the Gray Market, this week’s column is primarily animated by a single question with implications for multiple sectors of the art world. What’s slightly different this time out is that that I want to begin by posing the question directly to artists, dealers, collectors, curators, and everyone else who plays a role in determining the art that the rest of us will encounter across venues in the months and years ahead.

The question is this: Please, for the good of all the other work deserving a spotlight and shedding light on complex issues, can we just not do this whole Donald Trump thing again?

Some of you probably already have a sense of what I mean, but I’ll elaborate for clarity’s sake. Between the Republican primaries in early 2016 and the end of Trump’s term as president in early 2021, the art world in the U.S. almost continuously churned out show after show, and piece after piece, that somehow sought to engage with Trump, his administration, and/or his family. From gallery exhibitions and art-fair booths to biennials and NFT drops, these works tended to style themselves as statements of truth to presidential power. And at times, they felt as hard to escape as they were unable to transcend surface-level critique of a figure who prided himself on baiting the opposition into fits of rage and sanctimony.

If you asked me to honestly estimate the number of Trump-focused artworks that have aged well, I get no joy out of saying that my answer would be zero. This is even after I’ve spent the past couple of days digging back through the archives and checking with other people in search for any evidence that might lead me to a more nuanced opinion. I know I’m not the only one who feels this way, either. And yet, I’m also more and more certain by the day that, like it or not, we’re all in store for another anti-Trump art wave again in the 18 months between now and the 2024 election, if not the end of a second Trump term in 2029.

The main reason? Media outlets of all kinds are already being richly rewarded for shoveling their 2019-era chum recipe to an eager audience of news consumers—and there is an awful lot of crossover between the types of people happily engulfing this reheated sustenance and the types of people who make the U.S. and western European art world go ‘round.

Andres Serrano, Donald Trump (2004). Photo ©Andres Serrano, courtesy Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Brussels.

From a ratings and readership standpoint, Trump’s indictment on 34 criminal charges by a Manhattan grand jury is the best thing to happen to U.S. news producers in more than two years. Compared to the last six months of Trump’s presidency, average monthly traffic plummeted at media outlets across the political spectrum in the first six months of the Biden administration, according to data from Axios. The depth of the drop ranged from 27.3 percent among a collection of far-left outlets to a knee-buckling 43.8 percent among a collection of far-right outlets. (“Left-leaning” and “mainstream” news orgs fared the best of the group but still lost between 16.7 percent and 18.3 percent of their traffic on average.)

The decline in interest turned out to be more than just a blip. Although the partisan acrimony within the American political system has stayed on high, news organizations have consistently failed to draw the same level of audience engagement they regularly did while Trump was flying Air Force One.

Well, the “Trump bump” has returned in a major way over the past few weeks. When the former president turned himself in last Tuesday, the three top American cable news networks (Fox, CNN, and MSNBC) all averaged at least 1.5 million viewers for the first time in months, according to Nielsen. Legacy print media outlets, led by giants including the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal, are once again extruding Trump-based reportage and op-eds with military efficiency. Social media platforms are back to burning bright with political hot takes. Once again, half of the country believes the republic is about to launch into a golden age, half of the country believes the republic is in peril, and the business of news has never been better.

Crucially, the networks were actively courting this kind of response with their programming. Remember all those post-2020 calls for journalistic soul-searching and a better, wiser approach to covering sensationalist politicians? Turns out that they were more appealing in theory than in practice—even for cable execs serving the center and center-left.

This is all the more noteworthy because one of those networks, CNN, is now being led by a new CEO who entered the job aiming to reverse the tabloid instincts of his Trump-era predecessor, Jeff Zucker. Zucker (who exited CNN in 2022 after failing to disclose a romantic relationship with a subordinate) has been repeatedly flamethrowered for promoting Trump the candidate with the same zeal with which he promoted Trump the reality TV star during his days at the helm of NBC, the home of The Apprentice.

But it wasn’t as if Zucker preserved this playbook for Trump alone. Upon his CNN resignation, Patricia Sabga of Al Jazeera wrote that Zucker’s signature was to “[stretch] the definition of breaking news to drip-feed developments and outright speculation surrounding stories viewers became hooked on.” To typify this approach, she referenced an on-air interview in which CNN anchor Don Lemon asked an aviation expert if it was possible that missing Malaysian Airline flight MH370 “could have disappeared into a black hole,” to which the guest responded: “a small black hole would suck in our entire universe, so we know it’s not that.”

Judging by coverage of last Tuesday’s events, nascent CNN chief executive Chris Licht’s plan to turn the page on Zuckerism appears to be an idealistic memory. Here’s how Dylan Byers, the veteran media reporter at news upstart Puck, described CNN’s coverage of Trump’s surrender in Manhattan:

This week, CNN has gone all in on the Trump indictment in a manner that befits its historic import—almost all news organizations are doing this, to some degree—but also in a fashion that is at least somewhat reminiscent of Zucker’s CNN, circa 2015. Here, instead of the podium, we have nonstop footage of empty tarmacs, the gates at Mar-a-Lago, the plane landing in New York (captured from a speedboat), the convoy of black SUVs, the throngs of press and protestors, the courtroom doors, etcetera. The CNN anchors and correspondents call the play-by-play while analysts try to provide color commentary and the chyrons trumpet that “SOON: TRUMP LEAVES TRUMP TOWER FOR NY COURTHOUSE,” and then, in a breaking development, switch to announce that “ANY MINUTE: TRUMP LEAVES TRUMP TOWER FOR NY COURTHOUSE.”

Embarrassing as it sounds when put in those terms, the decision was a ratings bonanza for CNN. During a five-hour stretch last Tuesday, the network roped in about 5X its typical average viewership, saw its total audience numbers eclipse those of rival MSNBC, and briefly became the most-watched cable T.V. channel among viewers aged 25-to 54-years-old. The last time CNN reached these levels was the “earliest days of the Ukraine war” in February 2022, according to Byers.

All of this is a very bad sign for what we’re likely to see in the art world soon, especially if Trump once again becomes the Republican nominee for president in 2024—an outcome that looks more and more likely every day. Multiple polls show that he has only become more popular among Republicans after the indictment, widening his already substantial lead on Florida governor and calculating Ivy League mannequin Ron DeSantis. Even if Trump once again loses in the general election, we’re still set up for an extended repeat in more ways than one.

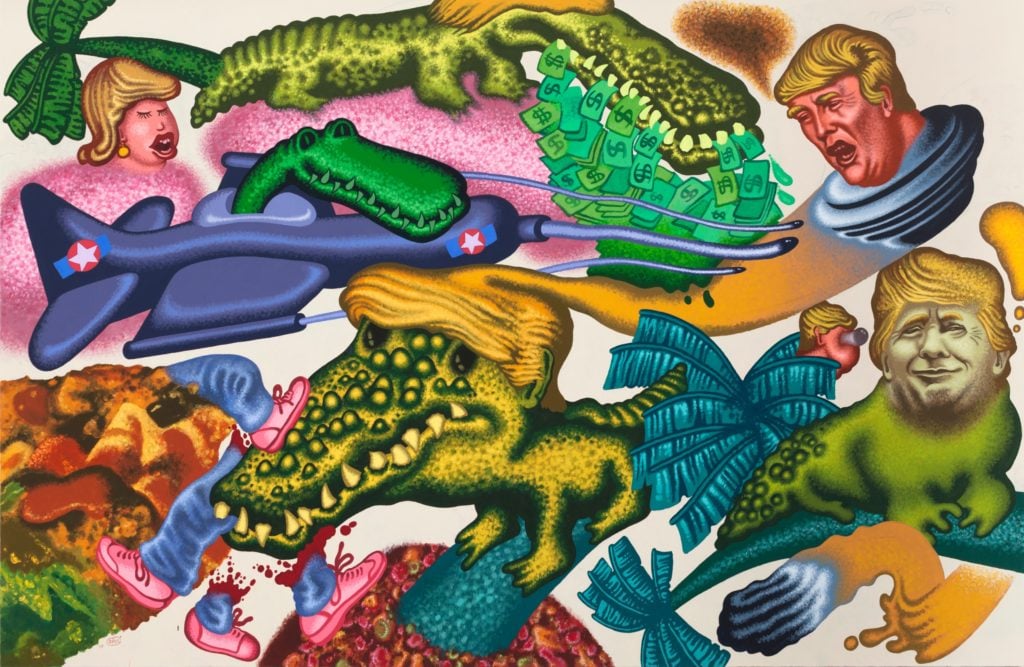

Peter Saul’s Donald Trump in Florida (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Mary Boone Gallery.

To be clear, I think Trump is a terrible person and a worse president. Putting aside the second wave of policy-based havoc that he would unleash back in the White House, his return to the top of the news cycle has already further inflamed the partisan zealotry that has come to define American politics in the 21st century. Whether inside or outside the art world, any person concerned about what would happen if he were re-elected is justified.

To me, however, Trump is mainly an attention-loving avatar inflated by longer-running, even more insidious tensions in American life: class tensions, race tensions, religious tensions, gender tensions, geographical tensions, and more. These conflicts pre-dated his improbable rise to the highest office in the land, and the past two years proved that his disappearance from the Oval Office did little to resolve or improve any of them. It’s just that no one in my lifetime has been as ready, willing, and able to embody the extreme right flank of these existential clashes as Trump.

To opponents of all types, these qualities make him a uniquely convenient target (partly because of his desire to perpetually play the victim). No wonder so many artists and art professionals fixated on him like a supervillain between his nomination in 2016 and the end of his term in 2021. When someone’s entire M.O. is to turn themselves into a caricature of what their enemies revile, those enemies don’t have to work very hard to find a justified outlet for their indignation.

Hence, scores of artists at all levels of the commercial hierarchy took to their studios to parody him, ridicule him, “expose” him, #resist him, “call him out,” and more during the four-plus years of his political run, time in office, and ignominius exit. But what did all this artwork accomplish in real sociopolitical terms? Next to nothing, as far as I can tell.

The results were the same even if you expanded the lens to include other forms of cultural production like theater, film, music, and literature. After Joe Biden defeated Trump in the November 2020 presidential election, my colleague Ben Davis diagnosed the problem as follows in a post-mortem headlined “Why the Art World Shouldn’t Be Congratulating Itself on Donald Trump’s Defeat”:

Joining battle at the level of the discourse, the commentariat went through a near-continuous ritual of getting excited and hyping the importance of some cultural figure who had called out the Trump regime: the cast of ‘Hamilton’ or Meryl Streep or Michelle Wolf. This happened even though, it bears repeating, the lesson of Trump’s first election was that figures like the cast of ‘Hamilton’ or Meryl Streep or Michelle Wolf were not nearly as politically consequential as had been thought.

The ensuing mainstream cultural texture… tended to blur together into anti-Trump symbolic theater. It was culture framed as if it were speaking truth to power. But really it was about making the pre-existing liberal audience for media and culture feel that it was still powerful, still tossing crumbs at Ivanka instead of the other way around.

So why did we in the art media spend four years slurping up practically every Trump-related artwork or exhibition that we could find, even those from artists or collectives whose day-to-day practice would otherwise have a hard time getting traction on our editorial calendars? Because a large audience kept clicking on those stories. It was our own version of the “Trump bump” enjoyed by cable news networks, political news websites, and legacy newspapers and magazines until the 45th president retreated to Florida following the January 6 insurrection and Biden’s swearing in. And just like their counterparts at those larger, broader-spectrum news organizations, decision makers in the art media are already charging across the high-dive platform to triple somersault back into the business of Trump-related coverage.

An Ivanka Trump look-alike model vacuums bread crumbs thrown by visitors as part of Jennifer Rubell’s art installation titled “Ivanka Vacuuming” at the Flashpoint Gallery on February 07, 2019 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

There’s another type of consumer to account for in this equation, too: art buyers. While I cannot personally recall seeing a single artwork focused on Trump, his administration, or his family that I would be interested in paying for even if I were a much wealthier person, I also wouldn’t watch cable news coverage of Trump’s arraignment, don’t care what Saturday Night Live or Jimmy Fallon have to say about this (or any other) issue, and would rather be tackled by an NFL linebacker than see Hamilton. I’m just not in the demographic for any of these things.

But there are enough collectors who are to make anti-Trump art commercially viable, at least if what we saw on the editions market, in top-flight galleries, at art fairs as prestigious as Art Basel and Frieze, and even in the parallel economy of NFTs since the 2016 election has been any indication.

Like the news consumers powering the relapse into panting coverage of all things Trump, sales of anti-Trump art represent a classic feedback loop. At its top end are mostly rich, establishment-liberal artists making work that will help rich, establishment-liberal buyers signal their establishment-liberal bona fides to like minds in their social and business circles while simultaneously convincing themselves that the acquisition represents substantive action toward preserving democracy, or fighting for women’s reproductive rights, or salving the humanitarian crisis of immigration at the U.S.’s southern border, or impacting any number of other legitimate societal ills that Trump’s face has come to stand in for to millions of people outside his political coalition.

There is an important exception to be made for artists and dealers who actually funneled the proceeds from sales of anti-Trump works into organizations that have done real good on the front lines of these causes. (If selling total agitprop secures housing assistance for a few more struggling people in America, more power to the artists behind it.) Beyond that, however, the perceived power in making or buying these works was an illusion the first time, and it will be no less of an illusion the second time. The fact that we even have to contemplate seriously a repeat of the Trump phenomenon is proof that the original multiyear surge of anti-Trump art did little, if anything, of real political import. Otherwise, why is Trump once again the most popular presidential candidate for one of the country’s two main parties?

Ultimately, it’s every individual artist, dealer, and buyer’s prerogative if they want to go in for a sequel to the anti-Trump art flood of 2016–2021. I’m not going to knock any hustle based on transactions between fully informed, consenting adults. But since the shared incentives at work in the media and the art market suggest that we’re all on the verge of being thrust back into this obsession again, let’s at least be candid with each other about the fact that it’s mostly just business.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: just because someone should know better doesn’t mean that they will.