Analysis

Impressionism Is 150 This Year. Is the Auction Industry Celebrating?

Amid perceptions of dwindling supply, the market for Impressionism has kept humming.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Impressionism’s birth in 1874, when 31 artists, including Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, and Berthe Morisot, staged an exhibition that shocked Paris. Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) inspired the movement’s name, which was coined contemptuously. In an article headlined “The Exhibition of the Impressionists,” critic Louis Leroy lambasted the work, writing that “wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”1

No matter. The Impressionists, and the Post-Impressionists who quickly followed in their wake, went on to become massively popular with the public and a titanic force in the art market. Impressionism has long been a principal area of focus for auction houses, which usually sell the genre alongside the Modern art it went on to inspire.

International institutions are commemorating the sesquicentennial with exhibitions devoted to masters like Monet, Morisot, and Vincent van Gogh,2 along with fresh scholarship that challenges the notion that the movement’s masterpieces amount to “playthings for rich people and fancy museums.”3 In 2023 in Paris, “Manet/Degas” was one of the Musée d’Orsay’s most popular shows of all time4 (later traveling to New York), and warmed the stage for its 2024 blockbuster, “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism,” which celebrates the exhibition that originated the movement.

In the art market, there is a perception that Impressionism has lost its luster over the years—that with prime material in museums, supply has declined alongside demand, as tastes have shifted to Contemporary stars.5 But what do auction statistics have to say? Artnet and Morgan Stanley investigated.

Methodology: Morgan Stanley collaborated with Artnet News using the Artnet Price Database to analyze the fine art market for works by Impressionist artists at auction from 2014 through 2023. All price data is drawn from the Artnet Price Database and includes the buyer’s premium, unless otherwise expressly noted. The Database includes only lots with a minimum estimate of $500 (for original paintings, sculptures, works on paper, photographs, prints and multiples, and installations with an identified artist). For this report, Artnet used publicly available information and its own historical research to create a data set that encompasses the works of approximately 120 relevant artists born between 1821 and 1874, excluding single-nationality Chinese artists. Both Impressionist and Post-Impressionists have been included, since some figures had practices that spanned those two intertwined tendencies. For the avoidance of doubt, all sale records come from the Artnet Price Database, as do all other figures cited in this report, unless otherwise noted. When adjusting for inflation, the Consumer Price Index as supplied by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics was employed.

I. Where Has the Impressionist Market Been, and Where Is It Going?

For decades, some of the biggest headlines in the art market have been generated by chart-topping Impressionist works: Monet’s La Terrasse à Saint-Adresse (1867) fetching £588,000 at Christie’s London in 1967 (about $5.5 million adjusted for inflation) and being acquired for the Metropolitan Museum of Art;6 Degas’s La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans (first exhibited in wax in 1881 and cast posthumously in bronze in 1922) selling for $380,000 at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York in 1971 ($3 million adjusted for inflation), a record at the time for a work of sculpture at auction;7 and Van Gogh’s Landscape with Rising Sun (1889) selling in 1985 at Sotheby’s New York for $9.9 million, then a record for an Impressionist painting at auction ($29.2 million in today’s dollars).8

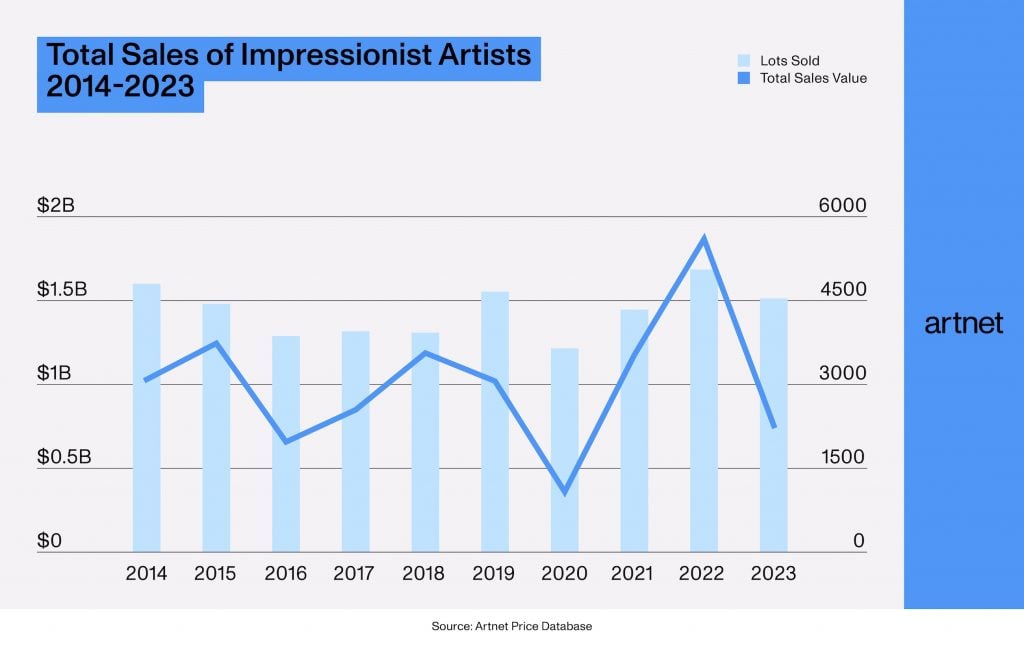

While there has been chatter since at least the mid-1990s of the supply of Impressionist work “thinning to a trickle,”9 the number of lots offered has remained relatively steady, according to the Artnet Price Database, averaging 6,091 lots annually for the decade. Setting aside the two outlier years of 2020 and 2022 (more on this below), genre sale totals have ranged between $656.1 million and $1.25 billion over the decade, with rises and dips reflecting the vagaries of what comes to market in any given year. Meanwhile, sell-through rates climbed from 66.8 percent in 2014 to a high of 77.2 percent in 2021; this number has not fallen below 75 percent in the two years since. The rise speaks, perhaps, to both the sustained demand for the genre, as well as the increasing care that auction houses take in orchestrating successful sales, including via guarantees and withdrawals. (Morgan Stanley and Artnet News took a close look at the financialization of the art market in last year’s Artnet Intelligence Report Mid-Year Review 2023.)10

In Covid-hobbled 2020, total sales of Impressionist art dipped to $349.2 million, but then shot to $1.87 billion in 2022, when a slice of Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen’s collection went to Christie’s, fetching $1.5 billion over the course of one evening, the highest total ever for a single auction. It was led by Georges Seurat’s Les Poseuses, Ensemble (Petite Version), 1888, which sold for $149.2 million, the decade’s top price in the category.11

In 2015, while the global auction market dipped six percent year over year, the Impressionist market grew some 21 percent, to $1.25 billion, its second-best year in the past decade, with Monet and Van Gogh as major contributors.12 That year, the sale of an Impressionist work of art averaged $281,394 at auction, compared to an average of $234,873 for the decade, and a less-robust $165,522 in 2023. In the first half of the decade, sell-through rates came in below 70 percent half the time; in the second half, they have never dipped below 70, and averaged 71.1 percent over the 2014 to 2023 decade. (By comparison, the sell-through rate for Contemporary art averaged 67 percent over the past decade, and topped 70 percent only twice, finishing at 72 percent and 71 percent, in 2021 and 2022, respectively.)

The sale of the David and Peggy Rockefeller estate at Christie’s New York in 2018 made the year the decade’s third-highest at $1.2 billion, helped along by an $84.7 million Monet, Nymphéas en fleur (1914–17). In 2018, the sell-through rate was a bit shy of the decade average, clocking in at 69.7 percent.

The Great Wealth Transfer

An unprecedented intergenerational wealth transfer is underway, with as much as $73 trillion expected to flow primarily from the Silent Generation and Baby Boomers into the accounts of Gen Xers, Millennials, and Gen Zers by 2045.13

Over the past decade, some blockbuster prices have been driven by such generational sellers: 18 out of the top 50 Impressionist prices were achieved in single-seller sales for (or sales billed as “including” the collections of) the Rockefellers, Allen, Anne H. Bass, Perry R. Bass, and Edwin Cox.

Half of the top 10 Impressionist works at auction during the decade came from the Allen sale alone, and half of the top 20 prices came from such single-owner sales.

The 1990s Versus the New Millennium

Nine of the top 20 Impressionist prices over the past decade came in its latter half, with Seurat’s $149.2 million Les Poseuses leading the way.

Correcting for inflation puts these highs in perspective. According to Artnet data, an all-time listing of the top 20 Impressionist prices includes three entries from more than 30 years ago, when Japanese buyers were flush. (These high-water marks have perhaps shaped perceptions of a decline.) Two of these works, when figuring for inflation, went for more than Allen’s Seurat. In 1990, paper magnate Ryoei Saito bought Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Au Moulin de la Galette (1876) at Sotheby’s New York for $85.9 million—$209.6 million in today’s dollars. That same year, Saito bought Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890) for $82.5 million, about $201 million adjusted for inflation, at Christie’s New York.

It is worth noting that, according to Artnet indices, the Impressionist genre exhibits one of the lowest levels of volatility across major collecting categories,14 making it a potential safe harbor in stormy times. Sure enough, amid the recent art market downturn, Hauser and Wirth could be seen selling a $4.9 million Manet in London at Frieze Masters in October 2024.15

II. Artist Case Studies Address Key Developments in the Impressionist Auction Market

1. Claude Monet: A Market Unto Himself

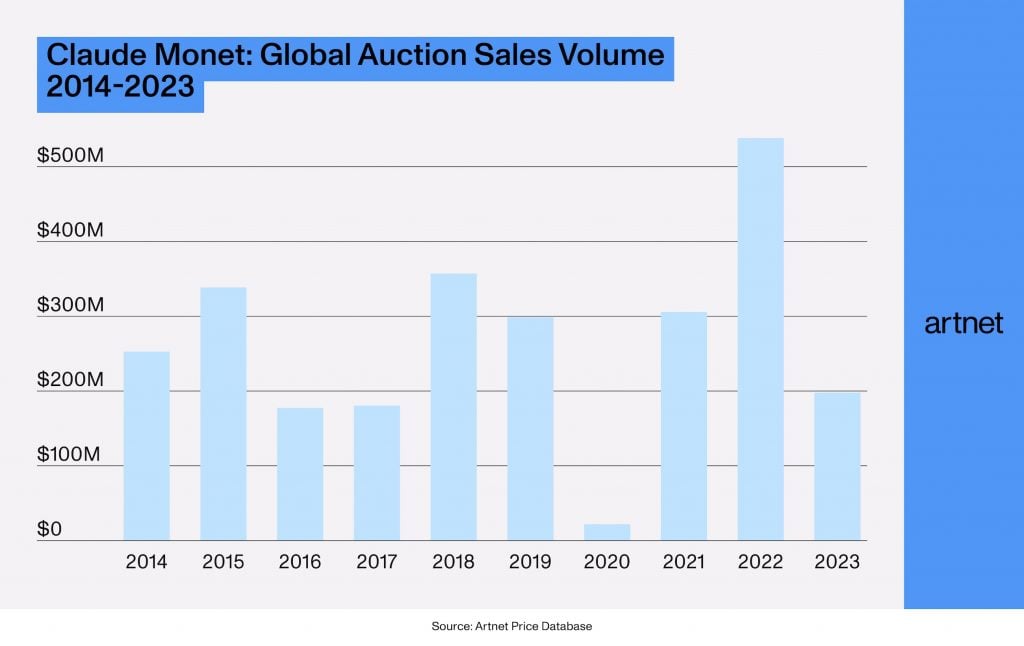

Perhaps the artist most closely associated with Impressionism, Monet has been one of, if not the most, dominant market presence over the past decade. (It helped that he was prolific.) His total sale volume was $2.67 billion on 286 lots sold, for an average of $9.3 million per lot, far outstripping the second in command of total sales volume, Van Gogh, who racked up $984.8 million on 100 lots sold. (The Dutchman did best the Frenchman in average sale price, at $9.8 million for the period.)

Monet’s auction record stands at $110.7 million for one of his legendary 1891 haystacks, achieved at Sotheby’s New York in 2019. Six of his all-time top 10 prices at auction have come since 2021, and nine of his all-time top 10 have been achieved since 2016; four were set by pieces held by Allen, Bass, or Rockefeller.

His total sales volume peaked at $539 million in 2022, the banner year for his works, when no fewer than four of his top 10 works came to the block. It dramatically outpaced his second-highest year of 2018, when sales totaled $298.7 million.

Setting aside the pandemic year of 2020, Monet’s annual sales never dipped below $150 million during the past decade; in half the years in the lookback period, it was at or above about $300 million. His sell-through rate, which averaged a robust 84.7 percent over the decade, also attests to unflagging demand: even in 2020, that figure dipped only to 78.6 percent, and exceeded 80 percent in eight out of 10 years, peaking at 92.3 percent in 2019.

2. Mary Cassatt: Women Still Trail Far Behind

Many collectors and institutions have made efforts to redress longstanding gender imbalances, pledging to buy more works by women artists, but perceptions of progress may be overstated. The 2022 Burns Halperin Report, looking back over more than a decade, found that institutional acquisitions of works by women artists peaked in 2009, and that art by women accounted for just 3.3 percent of all auction sales from 2008 to mid-2022.16

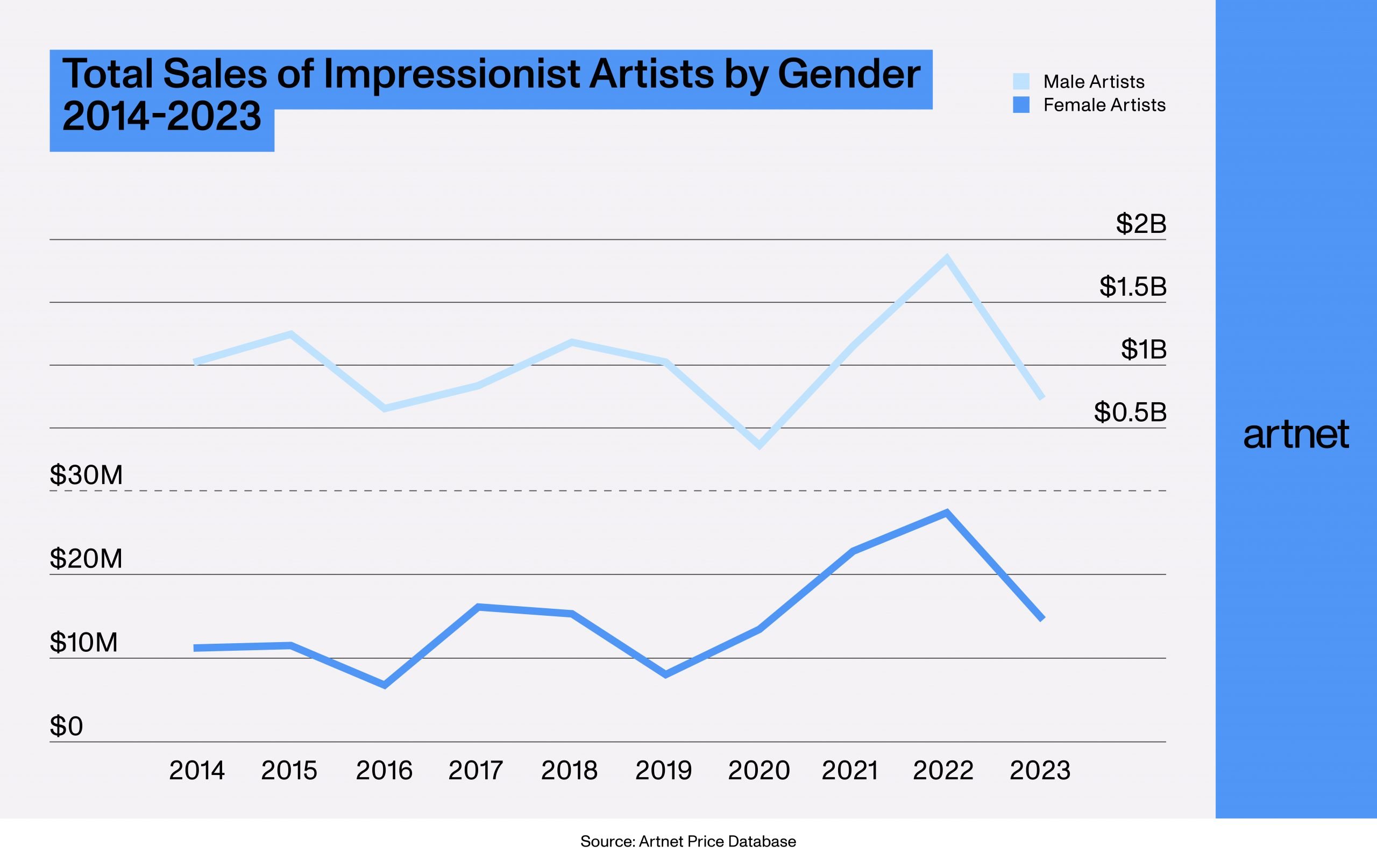

The market for work by women Impressionists in the last decade tells a similar tale, as seen in the below chart. Sales for men in the genre peaked in 2022 at $1.84 billion; the same year saw a total sales volume for women of just $27.4 million, also their peak for the past decade. The top 50 lots of the decade are all by male artists.

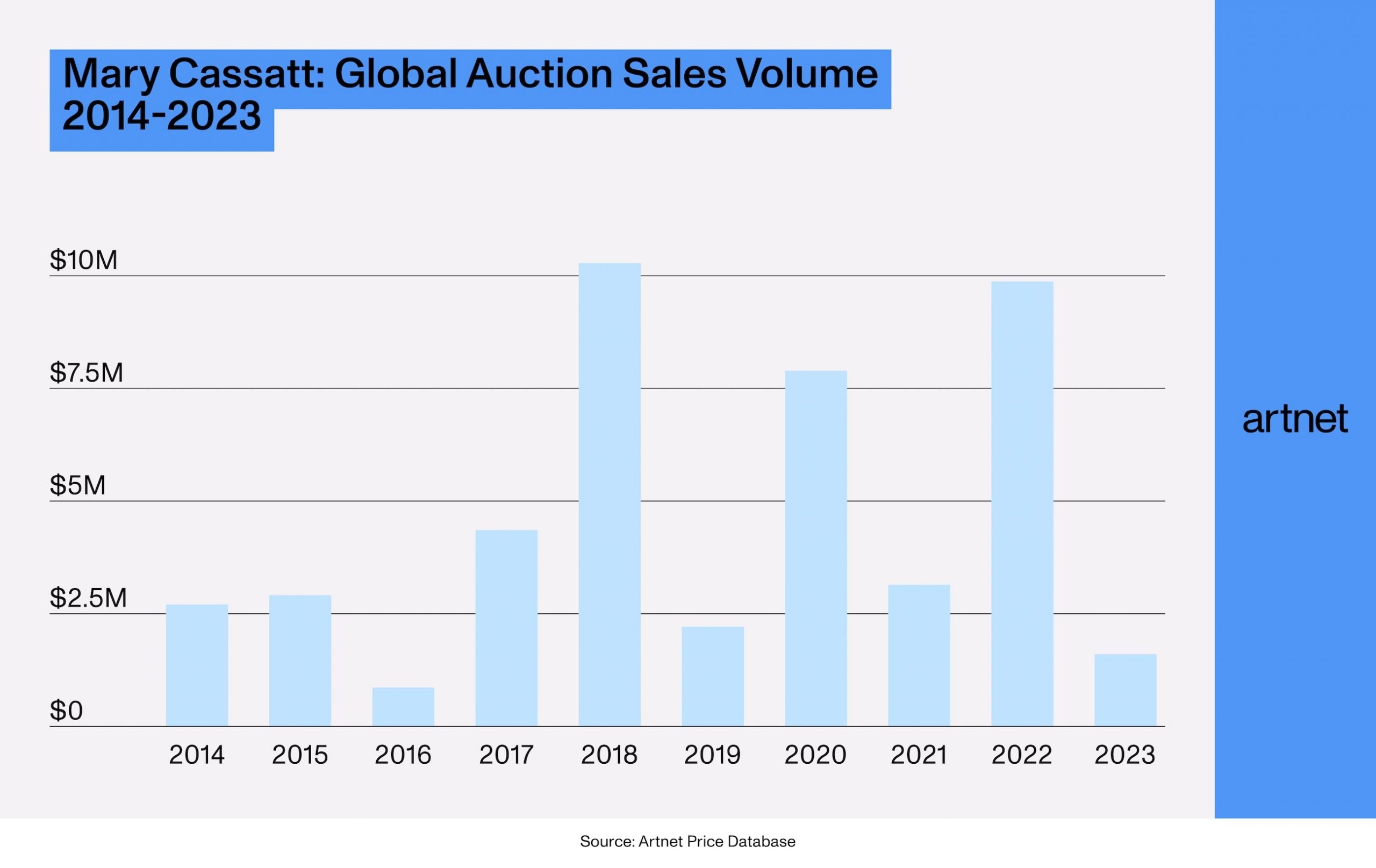

Mary Cassatt’s auction results provide a key example of this gender disparity. Over the past decade, the artist, best known for gauzy renditions of mothers and children, has had sales of just $45.8 million. Degas’s famous back-handed tribute, that he would not “admit that a woman can draw so well,”17 seems to have played out in the marketplace, and Cassatt ranks behind Impressionists with far less name recognition today, like Eugène Boudin, Max Liebermann, and Théo van Rysselberghe. She is the best-selling female Impressionist of the past decade, coming in at number 29 of all Impressionist artists. Just two other women appear in the top 50 Impressionists over the lookback period by sales value: Berthe Morisot and Emily Carr, trailing behind at 33 and 36, respectively.

Cassatt’s auction record high is modest in comparison to best-selling male Impressionists, at just $7.5 million, for her circa 1878 Young Lady in a Loge Gazing to Right, which hailed from the Ann and Gordon Getty Collection and sold at Christie’s New York in 2022. Her strongest year, 2018, saw a total sales volume of $10.3 million, much of it accounted for by two lots: Children Playing with a Dog (1907), for $4.8 million at Christie’s New York, and A Goodnight Hug (1880), for $4.5 million at Sotheby’s New York.

Some 48 of her works have exceeded the $1 million mark, and four of her top prices have been achieved since 2018.

Even as her yearly totals barely punctured the $10 million mark, Cassatt has had major institutional attention, regularly headlining exhibitions. “Mary Cassatt at Work” is on view at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco through January 26, 2025, after a run at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She was also the subject of recent solo outings at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris, and the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto.

The artist’s top-selling work at auction, and two others in her top 10, are works on paper, not painting, the medium that typically commands the highest prices. Young Lady in a Loge was made with pastel, gouache, watercolor, and charcoal with metallic paint; the other two are pastels, a newly popular medium in the 19th century18 that the artist often used.19

A bright spot surveying Cassatt’s performance over the decade: She just had her best year last year, with a whopping 48 percent of works on offer selling for above their high estimate, and only 41 percent selling for less than their average estimate. Both figures were her best for the decade.

3. Caillebotte: Acquisitions and Exhibitions Fuel a Reassessment

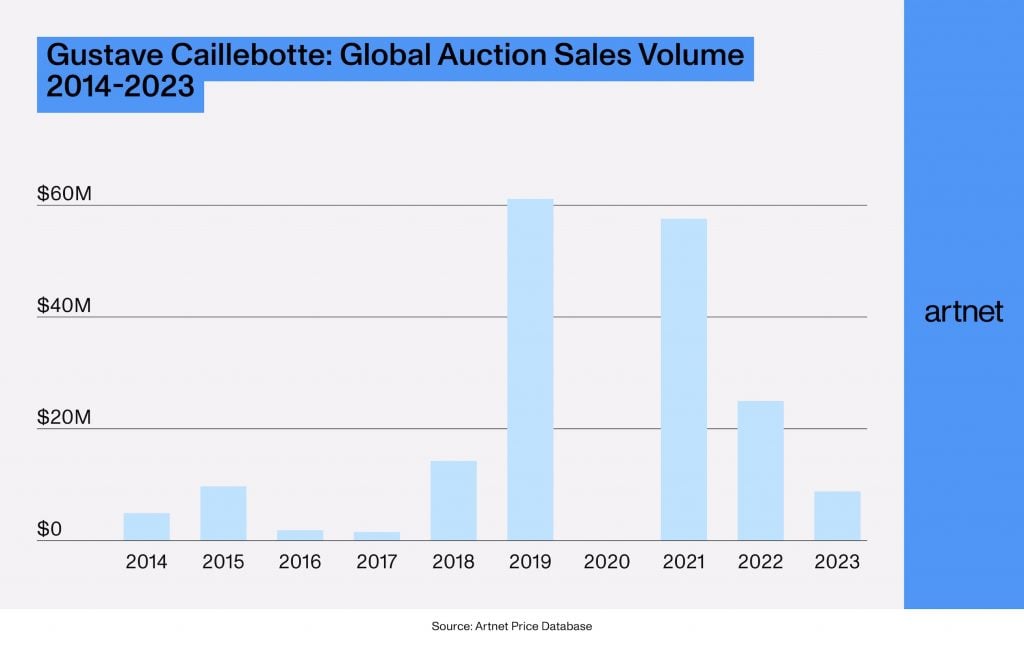

The market for Gustave Caillebotte saw significant spikes in the last decade, amid two touring museum exhibitions. The Frenchman painted variously in Impressionist and realist styles, depicting family scenes, interiors, and portraits. His works are relatively few in number, as he began painting in his late 20s and was dead by 45; after inheriting a fortune, he wasn’t dependent on selling his work, and much of it remains with his heirs.20 Until the Art Institute of Chicago’s 1964 acquisition of his iconic Paris, A Rainy Day (1877), he was a fairly neglected figure. Since 2000, a maximum of eight works has come to auction in any given year.

While no Caillebottes came to auction in 2020, this nadir was bookended by his two strongest years since 2000: In his peak year of 2019, his sales totaled $61.1 million, and in 2021, his sales amounted to $57.5 million. The latter figure was driven almost exclusively by Jeune homme à sa fenêtre (1876), his top-selling work, which fetched $53 million at Christie’s New York.

Such highs may suggest that institutional attention can help boost a market: They came a few years after the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., and the Kimbell Art Museum, in Fort Worth, Texas, co-organized “Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye” (2015–16). “Caillebotte: Painting Men” is currently on view in Paris at the Musée d’Orsay (through January 19, 2025), which organized it with the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, and the Art Institute of Chicago, where it will travel this coming June. This continued spotlight could augur more strong years for Caillebotte on the auction block—if potential sellers choose to come to market to test demand.

CONCLUSION

There has been a realignment of taste toward the art of the present, and a considerable number of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works have found their way into museum collections, which constricts supply.21 But Artnet’s statistics, showing a relatively stable market for this material over the last decade, suggest that there are still some collectors with a yen for these artists, while case studies reveal underlying nuances. Impressionist artists’ markets may also be less likely to soar or fall with the speed of Ultra-Contemporary figures.22 While the stratospheric prices of the late 1980s and early ‘90s may never return, a concentration of exceptional Impressionist sales in recent years demonstrates that the market for this material has not disappeared and continues to hold our attention.

Endnotes:

2. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/impressionism-at-150-shows-2482318

3. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/impressionism-150-review-2475151

4. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/09/arts/design/olympia-manet-degas-new-york-met-museum.html

6. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/12/05/

82164238.html?pageNumber=57

8. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/04/25/arts/art-sale-sets-record-for-a-van-gogh.html

11. https://news.artnet.com/market/paul-allen-sale-report-2207858

12. https://news.artnet.com/market/top-artists-at-auction-2015-434054

13. https://www.cerulli.com/press-releases/cerulli-anticipates-84-trillion-in-wealth-transfers-through-2045. Cerulli projects that wealth transferred through 2045 will total $84.4 trillion—$72.6 trillion in assets will be transferred to heirs, while $11.9 trillion will be donated to charities.

14. Artnet in the Deloitte Art & Finance Report 2023, 8th edition, p. 317.

15. https://news.artnet.com/market/frieze-masters-sales-report-2549007

17. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/10/04/archives/an-american-in-paris.html

18. https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/mary-cassatt-modernist-mother-child

19. https://huntington.org/verso/2021/03/connecting-mary-cassatts-pastels

20. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150706-caillebotte-the-painter-who-captured-paris-in-flux

21. https://www.barrons.com/articles/old-world-impressionists-impress-with-new-value-1427435131

22. https://news.artnet.com/market/primary-versus-secondary-market-prices-2455677

Disclosures

This material was published in December 2024 and has been prepared for informational purposes only. The information and data in the material has been obtained from sources outside of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (“Morgan Stanley”). Morgan Stanley makes no representations or guarantees as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or data from sources outside of Morgan Stanley.

This material is not investment advice, nor does it constitute a recommendation, offer or advice regarding the purchase and/or sale of any artwork. It has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. It is not a recommendation to purchase or sell artwork nor is it to be used to value any artwork. Investors must independently evaluate particular artwork, artwork investments and strategies, and should seek the advice of an appropriate third-party advisor for assistance in that regard as Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC, its affiliates, employees and Morgan Stanley Financial Advisors and Private Wealth Advisors (“Morgan Stanley”) do not provide advice on artwork nor provide tax or legal advice. Tax laws are complex and subject to change. Investors should consult their tax advisor for matters involving taxation and tax planning and their attorney for matters involving trusts and estate planning, charitable giving, philanthropic planning and other legal matters. Morgan Stanley does not assist with buying or selling art in any way and merely provides information to investors interested in learning more about the different types of art markets at a high level. Any investor interested in buying or selling art should consult with their own independent art advisor.

This material may contain forward-looking statements and there can be no guarantee that they will come to pass.

Past performance is not a guarantee or indicative of future results.

Because of their narrow focus, sector investments tend to be more volatile than investments that diversify across many sectors and companies. Diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss in a declining financial market.

By providing links to third party websites or online publication(s) or article(s), Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (“Morgan Stanley” or “we”) is not implying an affiliation, sponsorship, endorsement, approval, investigation, verification with the third parties or that any monitoring is being done by Morgan Stanley of any information contained within the articles or websites. Morgan Stanley is not responsible for the information contained on the third party websites or your use of or inability to use such site, nor do we guarantee their accuracy and completeness. The terms, conditions, and privacy policy of any third party website may be different from those applicable to your use of any Morgan Stanley website. The information and data provided by the third party websites or publications are as of the date when they were written and subject to change without notice.

This material may provide the addresses of, or contain hyperlinks to, websites. Except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, the firm has not reviewed the linked site. Equally, except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, the firm takes no responsibility for, and makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to, the data and information contained therein. Such address or hyperlink (including addresses or hyperlinks to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management) is provided solely for your convenience and information and the content of the linked site does not in any way form part of this document. Accessing such website or following such link through the material or the website of the firm shall be at your own risk and we shall have no liability arising out of, or in connection with, any such referenced website. Morgan Stanley Wealth Management is a business of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC.

© 2024 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC 4085791 12/2024