Analysis

State of the Art Market: Trophy Lots and the New Competitive Auction Landscape

A closer look at the market for trophy lots reveals how factors ranging from the location of a sale to the type of auction can affect performance.

A closer look at the market for trophy lots reveals how factors ranging from the location of a sale to the type of auction can affect performance.

Artnet News and Morgan Stanley

This article is part of the Artnet Intelligence Report Mid-Year Review 2023. Marking five years of our biannual Intelligence Reports, this inaugural half-year edition paints a data-driven picture of today’s art world, from the latest market results to the artists and artworks leading the conversation. Read the full report here.

As the fine-art auction market has grown more and more financialized in recent years, it has also grown more and more opaque to nearly everyone except the auction houses, their consignors, a small group of wealthy financiers who have become increasingly pivotal to the sector’s inner workings, and various agents and intermediaries for the aforementioned parties.1 The irony is that the business of auctions has never before delivered such impressive sales totals so consistently, even as it has never before so consistently presented such difficulty to observers hoping to plainly understand (let alone quantify) demand for individual lots, artists, genres, and the overall market.2

In an earlier era, perhaps the greatest impediments to a clear view of the fine-art auction market were mathematical, in that final prices reported by the auction houses included the buyer’s premium, a sizable fee owed by the winning bidder and calculated as a percentage of each lot’s hammer price (i.e., winning bid).3 Buyer’s premiums vary slightly from auction house to auction house, but in general, the percentage declines as the hammer price increases through a series of predetermined price brackets (which themselves differ slightly from house to house and from dominant regional currency to dominant regional currency).4 Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and other houses have also raised their buyer’s premiums multiple times over the years, making historical comparisons of demand in the fine-art auction market even more challenging.5

Auction houses have long preferred to communicate only the larger premium-inclusive prices to the media and the public, a practice that muddies comprehension of the auction market in multiple ways: first, by making it more difficult to seamlessly compare sales results with presale estimates, as the latter omit the buyer’s premium; and second, by intimating that competition for the lots in question was more active than actual bidding reflected.6 The complication radiates outward via auction price databases, which generally log only final, premium-inclusive prices to match each house’s public-facing records. (This is also true for the Artnet Price Database; all prices in this article include the buyer’s premium unless otherwise expressly noted.)

And yet, the houses’ preference for reporting premium-inclusive prices adds only a relatively modest amount of opacity in comparison with an array of extenuating financial circumstances negotiated between houses, consignors, financiers, and various intermediaries for select lots.7 Below, four of the most important such scenarios in the present-day fine-art auction market.

***

The auction house agrees to pay the consignor a guaranteed amount for one or more lots, regardless of the outcome of the public sale. While guaranteed lots are indicated as such to the public in presale materials (typically including a distinct icon in the online lot listing), the actual amount of the guarantee is known only by the house, the consignor, and any agent(s) working on behalf of the involved parties.

In advance of the public sale, the auction house secures an agreement from a third party to bid a certain amount for one or more lots. If the irrevocable bid wins during the live sale, then the irrevocable bidder acquires the lot, typically for that bid plus the buyer’s premium but less a financing fee paid by the house in the form of a discount on the final sale price. If another bidder tops the irrevocable bid, then the irrevocable bidder typically receives a percentage of the difference between their bid and the winning bid. While lots with an irrevocable bid are indicated as such to the public (typically including a distinct icon in the lot listing), the actual amount of the bid is generally known only by the house, the consignor, the irrevocable bidder, and any agent(s) working on behalf of the involved parties. (One minor nod to transparency: when an irrevocable bidder wins a lot, U.S. law requires houses to revise down the final sale price to reflect the discount given as a financing fee.)

The auction house agrees to pay the consignor a percentage of the buyer’s premium for one or more lots. Unlike guaranteed minimum prices and irrevocable bids, enhanced hammer deals still were not specifically indicated to the public by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, or Phillips as of June 1, 2023, and the actual amount paid to the consignor is known only by the house, the consignor, and any agent(s) working on behalf of the involved parties.

A party with a direct or indirect financial interest in a given lot registers to bid on said lot. Examples include a co-owner of the lot and a beneficiary of the estate from which the lot has been consigned. The only scenario in which the house discloses the identity of the financially interested party is when the auction house itself owns the lot in whole or in part. Even in this case, the house indicates to the public only that such an arrangement exists for a lot (typically using a distinct icon in the lot listing); the exact nature or size of the financially interested party’s stake is not detailed to the public.

***

As the definitions above show, these presale deals and ownership complexities create obstacles to understanding not only how much was paid for many lots but also who won them and through what mechanism, as well as which party bore the risk en route to the lots’ acquisition by new buyers. In fact, even the overview above simplifies the landscape to some extent; against the auction houses’ wishes, an unsanctioned secondary market for irrevocable bids has developed among financiers in recent years.12 Further, the above summary does not reflect financial arrangements made on the buyer side, including extended payment terms to attract bidders.

Houses and consignors have also become increasingly willing to voluntarily withdraw lots attracting relatively weak presale interest in order to prevent them from being publicly bought in (or “burned,” in auction parlance).13 This maneuver boosts sell-through performance at public auction, helps preserve lots’ future resale value for the owners, and can provide appealing inventory for the houses’ private sales departments, which undertake the job of finding buyers for works under more discreet, less pressurized conditions.14

Whether coincidentally or not, the recent rise in presale withdrawals has taken place alongside multiple larger shifts toward opacity in the fine-art auction sector. Major auction houses, including Christie’s and Phillips, have reduced or discontinued production and distribution of physical auction catalogues since 2020.15 This decision has made it even harder to track withdrawn lots, which are typically removed entirely from the houses’ public-facing online records.16 Upon being acquired by telecom magnate Patrick Drahi’s BidFair USA, in 2019, Sotheby’s joined the world’s two other largest auction houses—Christie’s and Phillips—in being privately owned and thus freed from the requirement to publicly report extensive financial results on a regular basis.17 Last but not least, in the summer of 2022, New York City repealed all industry-specific regulations governing auctioneers, thereby allowing houses of all sizes to disclose less information to consignors, bidders, and the general public than before.18

However, at least one certainty remains in this increasingly complex market: every year, fine artworks in the market’s uppermost price echelon have an outsized effect on the overall performance of fine art at auction. More specifically, the availability and performance of so-called trophy lots—works of fine art sold for more than $10 million each—have never been more important.19 In 2022, lots sold for more than $10 million each made up the single largest portion of the fine-art auction market by value, and this price bracket was also the only one to increase in total sales year over year, according to the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.20

The financialized nuances of the fine-art auction market impact the highest-priced lots more than any other sector of the market, whether the focus is on house guarantees, withdrawn lots, or other extenuating circumstances.21 This makes intuitive sense: the higher the stakes, the more inclined sellers and auction houses alike may be to limit their downside risk using the tools available.

The major Christie’s and Sotheby’s evening auctions held in New York in May 2023 provided a sampling of the financial aspects of the 21st-century auction landscape. The executors of the S.I. Newhouse estate negotiated a guarantee to cover all works from the collection offered by Christie’s, including in its latest dedicated single-owner evening sale, on May 11, 2023.22 In contrast, the heirs of the Gerald Fineberg estate opted for an enhanced hammer deal from the same house on all works consigned from the collection.23 The dangers of eschewing house and/or third-party guarantees were exemplified when Picasso’s Femme assise au chapeau de paille (MarieThérèse) (1938), carrying a presale estimate of $20 million to $30 million, failed to sell on a maximum bid of $18.5 million during Christie’s 20th-century art evening auction.24

Sotheby’s, meanwhile, made minimum price guarantees for the star lots in its marquee May evening sales, then accepted irrevocable bids for both works: Gustav Klimt’s Insel im Attersee (1901–02), which hammered at $46 million, slightly above its estimate in the region of $45 million; and Louise Bourgeois’s Spider (1996), which hammered at its low estimate of $30 million.25 Sotheby’s also withdrew Yoshitomo Nara’s 1998 painting Haze Days, despite its status as the anchor lot of “The Now” evening sale; the work had the highest estimate ($12 million to $18 million) of the event but, notably, no house-guaranteed minimum price or irrevocable bid.26

The relationship between the growing importance of trophy lots and the growing financialization of the fine-art auction market is symbiotic. As prices for the most sought-after artworks have escalated to higher levels, the cost of losing such artworks to a rival auction house has escalated in kind, along with the financial arrangements required to win consignments and incentivize buyers.

This dynamic has created something of a feedback loop at the apex of the auction market for fine art: as the owners of highly prized artworks have seen estimates and sale prices in the auction sector rise significantly, the potential for similar (if not greater) gains has motivated them to drive harder bargains when consigning to major auction houses, which must then compete to offer the most favorable terms, incentivizing the houses to offset the corresponding financial risk by negotiating irrevocable bids with third parties. But by ensuring that trophy lots continue to sell for tens, if not hundreds, of millions of dollars through such financialization, the houses arguably put pressure on themselves to repeat the process with the next wave of major auctions.

Recent auction data helps us frame the scale and proliferation of prices, guarantees, and irrevocable bids herein. Across the nine fine-art evening auctions held in Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips’s New York salesrooms in May 2023, the three houses made minimum price guarantees for 87 out of the 332 lots on offer before withdrawals (26.2 percent by volume). The combined low estimate of the 87 guaranteed lots was $730.9 million, an amount totaling roughly 57.1 percent by value of the $1.28 billion aggregate low estimate of all 332 works in those same auctions.27 Yet the houses also accepted irrevocable bids on 85 lots whose combined low estimates reached $663.5 million, equating to roughly 52 percent by value of the aforementioned $1.28 billion aggregate low estimate.28

In terms of the impact on trophy lots, we have utilized the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics to determine that 32 artworks in the above auctions carried presale low estimates of more than $10 million each, with their aggregate low estimates totaling $648 million. Of those 32 lots, we found that 22 of them (68.8 percent by volume) came with house guarantees, and 22 (68.8 percent by volume) also had irrevocable bids. Further, we calculate the combined low estimate of the lots with house guarantees was $489 million, while the combined low estimate of the lots with irrevocable bids was $487 million—meaning each financial arrangement had been made for just over 75 percent of the $648 million low estimate of all trophy lots by value.

Although the data above covers only one seasonal auction cycle in one major auction market, it suggests that trophy lots correlate to the financialization of the fine-art auction sector much more strongly than works in lower price brackets. In the absence of comprehensive public data about the dollar value of guarantees and irrevocable bids, studying the performance of trophy lots becomes perhaps the best proxy for understanding the private machinations that increasingly shape the peak of the public auction market.

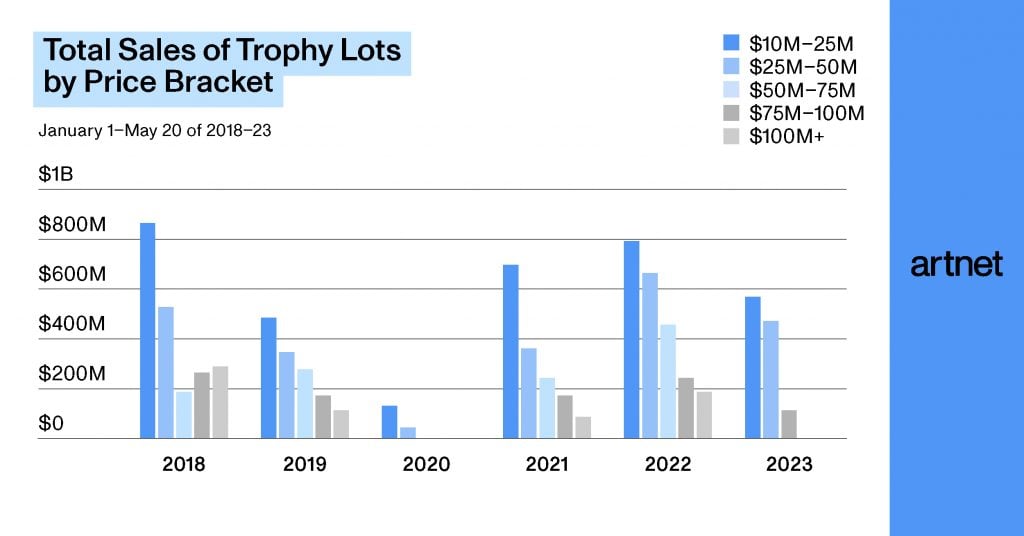

Our analysis looks at the price bracket for lots sold above $10 million from January 1 through May 20 in each year since 2018. In concert with the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics, we separated the broad “trophy lots” price bracket into a series of more specific high-end brackets: lots sold for more than $10 million through $25 million; lots sold for more than $25 million through $50 million; lots sold for more than $50 million through $75 million; lots sold for more than $75 million through $100 million; and lots sold for more than $100 million.

To provide further insight, we examined those price brackets’ interaction with secondary factors, including genre of artwork, city of sale, and type of evening auction (meaning, the regularly scheduled “marquee” evening sales, with the highest-priced lots, held seasonally by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips worldwide, versus premier single-owner collection evening sales). The analysis focuses on fine art, which includes paintings, works on paper, sculptures, prints, photographs, digital artworks, and more, from artists born from 1250 to the present; it excludes decorative art, defined here as encompassing antiques, antiquities, and collectibles of all other types.

Source: Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

The data shows that the trophy-lot category is not quite as top-heavy as one might think: the 15 lots that sold for more than $75 million during the sample period since 2018 made up about $1.5 billion, or only about 17.5 percent, of the $8.8 billion in sales generated by all trophy lots during that period.

In terms of total sales of trophy lots, the only year in the sample period quieter than 2023 was 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic upended the auction calendar. Less than $1.2 billion worth of trophy lots changed hands between January 1 and May 20, 2023—and no lots at all traded for more than $75 million. The only other year in the data set where that happened was, again, 2020.

In fact, the dollar value of trophy-lot sales in 2023 was less than half the $2.4 billion generated by such sales in 2022, when the “Big Three” houses’ usual marquee evening art auctions were supplemented by dedicated single-owner auctions of works from the collections of Texas oil heiress Anne H. Bass; Swiss sibling art dealers and collectors Thomas and Doris Ammann; real-estate tycoon Harry Macklowe and his ex-wife, Linda Macklowe; and David M. Solinger, the first president of the Whitney Museum of American Art who was not a member of the Whitney family. (More details on the sales split between these two categories later.)

In terms of quantity, in only two years were fewer trophy lots sold during the sample than the 53 traded in 2023. Those years were 2019, which saw 51 lots sold for more than $10 million, and 2020, which saw only eight such lots. Supply was especially limited at the top: in 2023, no lots at all had been sold in the price brackets above $75 million by May 20; the only other year for which this was the case was 2020. (More on supply when we look at trophy lot sales by auction type later.)

Source: Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

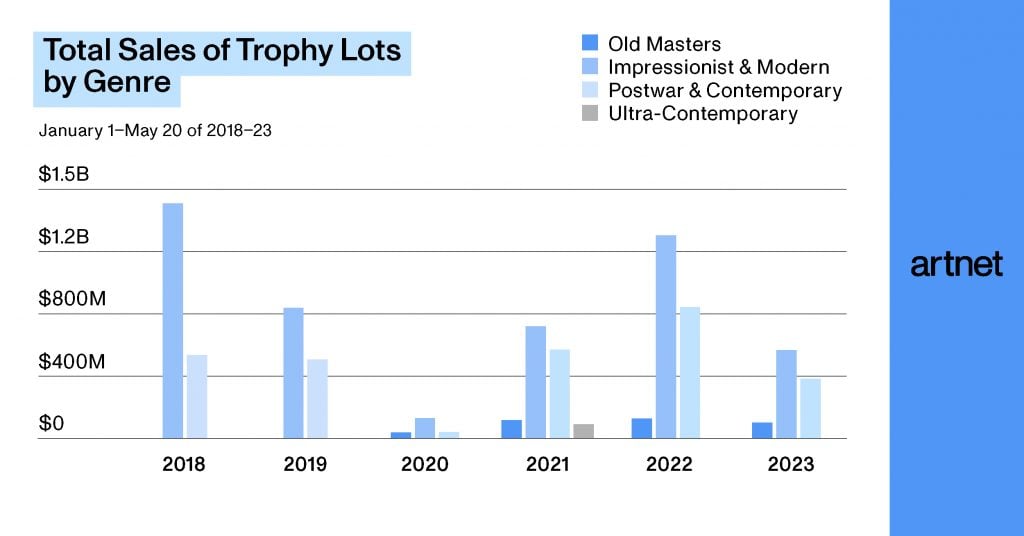

Trophy-lot sales volume remained concentrated in Impressionist and Modern works (defined here as those made by artists born from 1821 through 1910) throughout the data set, especially when it comes to fine artworks sold for more than $50 million. Except in 2020, the Impressionist and Modern genre did not see aggregate trophy-lot sales dip below $600.5 million (the 2023 total) during the sample period, and there were only two years in the past six (2020 and 2023) in which the genre generated less than $325.4 million in sales for artworks traded for more than $50 million each.

Even the closest competitor to the Impressionist and Modern genre—the Postwar and Contemporary genre (defined here as consisting of works made by artists born from 1911 through 1974)—has lagged significantly behind.

Postwar and Contemporary trophy lots have not outsold their Impressionist and Modern counterparts by value. The closest they came was in 2021, when the sales volume for Postwar and Contemporary trophy lots was $586 million against $727.8 million in sales for Impressionist and Modern trophy lots. The biggest divide between the genres was in 2018, when the $1.5 billion worth of Impressionist and Modern trophy sales topped the equivalent total for Postwar and Contemporary ($546.7 million) by more than $953 million.

Old Master trophy lots have performed better since the pandemic than before, generating at least $80 million in total sales in the sample period of every year since 2021. (We define Old Masters as artists born from 1250 through 1820.) In contrast, only one trophy lot by an Ultra-Contemporary artist (defined as any artist born in 1975 or later) was sold during the sample period: Beeple’s Everydays – the First 5000 Days (2021) in 2021, for $69.3 million. (See the final section of this article for more details.)

Source: Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

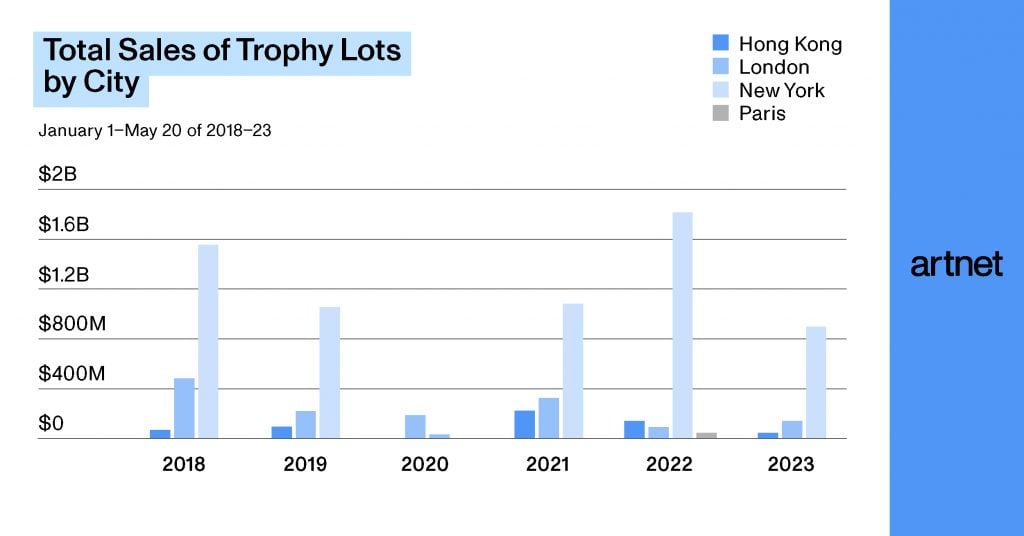

New York City was the dominant market for fine artworks sold for more than $10 million in the studied period. The exception was the COVID year of 2020, when London bested New York by roughly $91 million in trophy-lot sales—a quirk of timing, in that London’s major February evening sales were able to go on as planned, whereas the virus’s subsequent spread forced the postponement and restructuring of the usual marquee evening sales in New York in May.29 Otherwise, London routinely placed a distant second, trailing New York in trophy-lot sales by at least $726.9 million each year during the sample period.

The disparity was especially pronounced when it came to artworks that sold for more than $50 million each at auction. Setting aside 2020, the closest the two hubs were at this price level was in 2023, when New York auction houses sold $120.3 million worth of fine artworks traded for more than $50 million each and London houses sold none at all. London’s apex in such transactions arrived in 2022, when the city’s auction houses sold $187.5 million worth— and New York’s sold $709.6 million worth. New York and London were the only two cities that sold even a single fine artwork for more than $50 million during the period studied. In 2022, London became the only city besides New York where an artwork sold for more than $75 million in any of the past six years through May 20, when L’empire des lumières (1961) by René Magritte found a buyer for more than $79.4 million in 2022.

Except for the industry-wide anomaly of 2020, Hong Kong trended up steadily as a trophy lot sales destination in the period studied. Sales at the top of the market peaked at nearly $213.8 million in 2021. However, they fell by nearly 50 percent year over year in both 2022 and 2023, to $139 million and $67.4 million, respectively. This tracks with a larger drop in supply spread across all price brackets in Hong Kong in 2022—perhaps an effect of the unusually high number of works to have come to auction the prior year—as well as larger strains on the Chinese macroeconomy in 2023.30 Paris has been trending up in this competition lately. Granted, it took until 2021 for the city to sell its first trophy lot: another Magritte painting, La vengeance (1936), which brought roughly $17.4 million in its auction debut. Paris nearly quadrupled its trophy-lot sales year over year, selling three works for a combined $65.4 million in 2022 before coming up empty in 2023.

Source: Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

Although sales of trophy lots in marquee evening auctions at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips peaked in 2018 at just under $1.5 billion, such auctions have delivered less than $1.2 billion worth of such sales only twice during the sample period: the outlier COVID year of 2020 and 2023. Sales of trophy lots in marquee evening auctions were down nearly 43 percent by value year over year through May 20, 2023, with total sales landing at $823.4 million. Notably, no fine artworks traded above $75 million in marquee evening auctions in 2023, while at least two lots sold at that lofty price level in every other year in the data set except 2020.

Single-owner sales have become an increasingly large part of the conversation surrounding auction performance in recent years, but their impact on trophy-lot sales has been volatile during the sample period. One year after $590.6 million worth of trophy-lot sales were generated via single-owner evening auctions in 2018—notably, the year that the Peggy and David Rockefeller collection set a then-record for the largest single-owner collection at auction, largely thanks to a dedicated evening sale in May—the same figure for the relevant period dropped to a mere $45.1 million. After an understandably silent showing in 2020 ($0), trophy-lot sales in single-owner evening auctions rose to $142.7 million in 2021. Then, in 2022—when works from the Ammann, Bass, Macklowe, and Solinger collections were the subject of dedicated evening auctions—that number burgeoned more than fivefold, to $746.7 million, before receding to $241.4 million in 2023.

The supply (or lack thereof) of the very highest-priced lots marked the difference between healthy and anemic years of trophy sales in single-owner evening auctions during the period studied. Setting aside 2020, when zero trophy lots were sold in single-owner evening auctions, the three worst-performing years (2019, 2021, and 2023) saw no lots at all sell for more than $50 million each in single-owner evening auctions. By contrast, the best-performing year (2022) saw four such lots bring a total of $394.3 million in single-owner evening sales, while the second-best-performing year (2018) saw three such lots bring $280.4 million. Taken together, the data suggests that any year of high-volume trophy-lot sales in single-owner evening auctions is routinely followed by a down year of the same, a correlation that likely speaks to the reliance of single-owner evening auctions on estate sales of extreme consequence, the timing of which are unpredictable by nature. (The Macklowe auction, the result of a divorce settlement, is the rare exception.)

Although the single-owner evening auctions’ trophy-lot sales were therefore uneven in the relevant period, their volume increased appreciably over time compared with the equivalent in marquee evening sales in the timeframe examined. In other words, the overall supply of artworks selling for more than $10 million each seems to depend more and more on the number of major single-owner collections offered in standalone evening auctions over the time period in question. While the two figures diverged by nearly $1.3 billion in 2019, the differential declined to slightly more than $1 billion in 2021, then to $692.3 million in 2022, and finally to $582 million in 2023. Only time will tell if this trend persists, but it is a relationship that bears watching.

Complementing the macro analysis in the prior section, below are capsule studies of six trophy artworks. All were selected from a list of the 15 highest-priced fine artworks sold at auction during the January 1 through May 20 sample period from 2018 through 2023. Each artwork was chosen for how it illustrates or expands upon one or more major themes discussed.

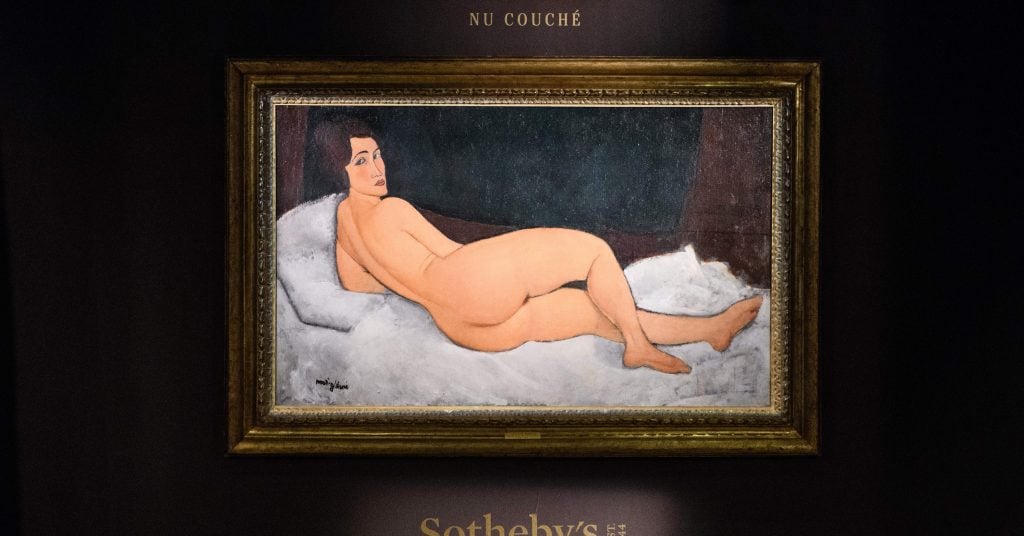

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu Couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917). Photo by Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images.

Based on macro data, Modigliani’s reclining nude represents the platonic ideal of a trophy lot in terms of genre (Impressionist and Modern) and city of sale (New York). Impressionist and Modern artworks accounted for between 55.8 percent and 73 percent of trophy-lot sales by value in every year studied except 2021, when the genre accounted for only 49.3 percent ($727.8 million) of the nearly $1.5 billion worth of sales.

The New York skew was even more pronounced, as auctions in the city sold between 66.1 percent and 85.1 percent of all trophy lots by value in five of the past six years. (Here, the anomalous year was unsurprisingly 2020, when New York houses sold two trophy lots for a combined $29 million, roughly 14.9 percent of the $194.9 million worth of such artworks sold at auction worldwide.)

Nu Couché (sur le côté gauche) is also one of just five lots sold for more than $100 million during the sample period since 2018—and one of just two sold for more than $150 million. However, the high-stakes work hammered at $139 million, considerably below its $150 million presale estimate; it also carried an irrevocable bid.31

Jeff Koons, Rabbit (1986). Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images.

In 2019, Rabbit became the most expensive fine artwork by a living artist ever sold at auction. Part of the reason this record still stands more than four years later is the gleaming metallic sculpture’s sterling provenance—a major driver of value among trophy lots. Rabbit came to Christie’s from the estate of publishing tycoon and renowned collector S.I. Newhouse, who acquired it from Gagosian in 1992 and kept it in his collection for the remainder of his life. Gagosian, for his part, bought the sculpture from a private collector who had acquired it on the primary market from Koons’s then-gallerist, the famed Ileana Sonnabend.32 This made the May 2019 Christie’s sale not only the first time Rabbit had returned to the market in 27 years but also the first time it had ever appeared at auction, ensuring that it was fresh to market and thus a significant draw to buyers. The work was offered without a house guarantee or an irrevocable bid.

In retrospect, the sale of Rabbit signified that the fine-art auction market had entered an era in which demand for Postwar and Contemporary trophy lots rivaled that for more time-tested works. It marked the first time in the period studied that a work from the Postwar and Contemporary genre sold for more than $75 million. In fact, two such lots found buyers at this lofty price level on the same night: Rabbit, and Robert Rauschenberg’s silkscreen Buffalo II (1964), which Christie’s New York sold for $88.8 million.

The combined $179.9 million brought by that pair eclipsed the equivalent total brought by all Impressionist and Modern lots that sold for more than $75 million that year. (The only entry in the latter category was Claude Monet’s 1891 haystack painting Meules, which sold for $110.7 million at Sotheby’s New York a day earlier.) The Postwar and Contemporary genre repeated this feat in 2022, proving that the dynamic created by Rabbit was not a one-time occurrence.

David Hockney, The Splash (1966). Photo by Daniel Leal/AFP via Getty Images.

That The Splash (which carried a house guarantee from Sotheby’s) was the top-selling fine-art lot during the sample period in 2020 highlights just how anomalous that pandemic year was for the auction sector. At roughly $29.9 million, The Splash would not have been among even the 10 priciest lots in any other year in the period studied.

It was not even a particularly expensive work by Hockney. Consider, for example, that his Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) (1972), sold for an artist record of $90.3 million in November 2018.33 For comparison within the sample period, note that Hockney’s double portrait Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott (1969) sold for £37.7 million ($49.5 million) in March 2018—only the ninth most expensive lot by any fine artist to change hands during the sample period that year.

Due to extraordinary global events that disrupted the auction calendar, many consignors chose to hold their choicest works back from the market in 2020.34 Only eight fine artworks fetched more than $10 million between January 1 and May 20 that year. Notably, six were sold in London during the month of February. The other two crossed the auction block in New York’s January sales of Old Masters and brought a combined total of barely more than $29 million—about $900,000 less than The Splash on its own.

These sales further contextualize how and why London auction houses outperformed New York’s in total sales of trophy lots during the sample period in 2020—again, the only time London has done so since 2018. The Splash was not just the only artwork to be sold in London for between $25 million and $50 million; it was the only fine-art lot to be sold for more than $25 million anywhere in the world in 2020. For comparison, four works were sold in London for more than $25 million during the equivalent period in 2019 and 2022, respectively, while New York auction houses sold at least 12 artworks for more than $25 million each during the sample period of every year under examination, with the lone exception of 2020.

Beeple, Everydays: the First 5000 Days (2021). Photo by Roslan Rahman/AFP via Getty Images.

Everydays – the First 5000 Days, a digital collage backed by an NFT, was responsible for a string of “firsts” and “onlys” among the annual lists of the 15 top-selling fine artworks at auction during the period ending May 20. It is the first and only one made by an Ultra-Contemporary artist (defined as artists born in 1975 or later); the first and only digital trophy lot; the first and only trophy lot sold in an online-only auction; and the first and only trophy lot to be sold directly from the artist’s studio during the sample period.

Experts can debate whether these traits make Beeple’s (aka Mike Winkelmann’s) work a turning point, an exception that proves the rule, or something in between. What is without question is that its unexpectedly high price initiated a surge of interest in NFTs in the fine-art auction sector that has had a lasting legacy. Though results have yet to be repeated at this level, Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips all still regularly offer NFTs in 2023, and nearly two years ago, Sotheby’s even launched a dedicated platform for blockchain-based works called Sotheby’s Metaverse.35

Although it may seem unusual in retrospect that the work carried neither a house guarantee nor an irrevocable bid, it is important to remember that Christie’s started the bidding for Everydays at $100, implying that the work was not considered a trophy lot before the sale.36 Yet it is now in rare company. Across all genres, only 36 works have sold for more than $50 million during the sample period from 2018 through 2023, good for a combined $2.8 billion worth of sales.

As in the Ultra-Contemporary genre, only one Old Master artwork sold at this level through May 20 in each of the past six years: Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, for $92.2 million. Of the remaining 34 fine artworks traded for more than $50 million during the period examined, 25 are by Impressionist and Modern artists, and the remaining nine are by Postwar and Contemporary artists.

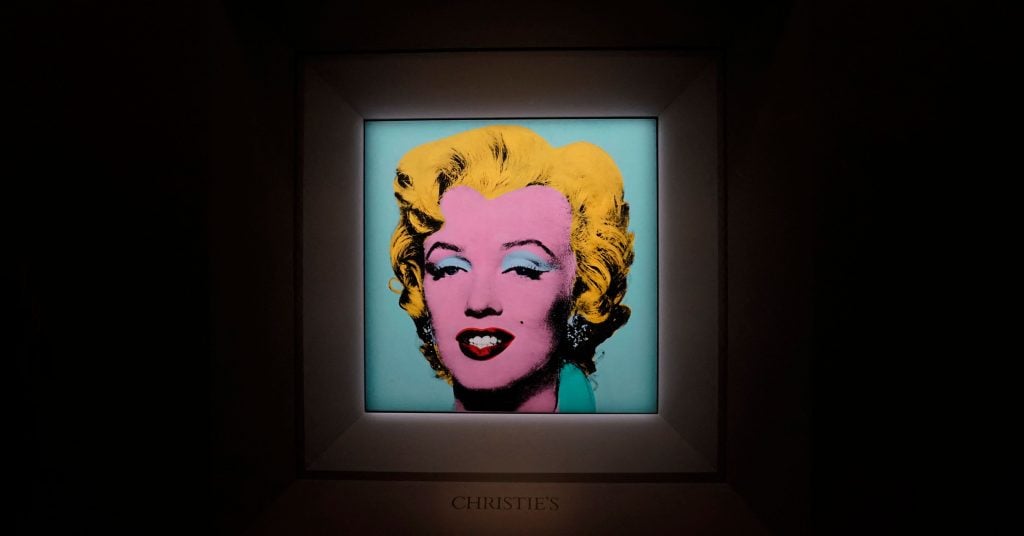

Andy Warhol, Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964). Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images.

Thanks to this transaction, Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn became not only the priciest fine-art lot of any kind sold since Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, which brought $450.3 million in November 2017, but also the most expensive work by an American artist ever sold at auction.37 Exceptional provenance again played a role. The painting passed through S.I. Newhouse’s collection en route to the equally esteemed collection of the Swiss art-dealing Ammann siblings, whose family it stayed in for 36 years before being offered at auction for the first time in 2022.38 It carried neither a house guarantee nor an irrevocable bid, and it is possible that the Ammanns’ executors left money on the table as a result given that the work hammered at just $170 million ($195 million after fees), below its unpublished $200 million estimate.39

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn also reflects the recent importance of single-owner evening auctions within the realm of fine artworks sold for more than $10 million each. In 2022, such auctions generated $746.7 million worth of sales of fine-art trophy lots during the sample period, or 34.2 percent of all such sales by value across all evening auctions staged through May 20. While that share is the highest of any year in the sample, it is not a complete outlier. In three of the past six years (including 2023), single-owner evening auctions accounted for at least 22.7 percent of all trophy-lot sales by value in evening auctions.

Single-owner sales have been an even greater factor when it comes to fine artworks sold for more than $100 million at auction in recent years. Only five such works have traded during the sample period since 2018. Of those five, three were sold in marquee evening sales, generating $371.3 million in total. The other two (including Shot Sage Blue Marilyn) were offered in single-owner evening sales and brought a combined $310 million. Of the $681.4 million worth of fine artworks that traded for more than $100 million each at auction, then, about 45.5 percent of sales by value came from single-owner evening sales, versus roughly 54.5 percent from marquee evening sales.

Zhang Daqian, Pink Lotuses on Gold Screen (1973). Photo by South China Morning Post / Alamy Stock Photo.

Equipped with a house guarantee and an irrevocable bid, this painting was auctioned from the family collection of Chinese textile entrepreneur C.S. Loh, whose wife acquired it directly from the artist in 1973.40 It exemplifies the fine-art auction market’s rise in Hong Kong in recent history, including in the post-pandemic era.

Of the top 15 lots by price in each year of the sample period since 2018, only three were sold in Hong Kong. Pink Lotuses on Gold Screen is the most recent of the transactions; the other two took place in 2021. Together, the trio fetched HK$804.8 million ($103.3 million), or 17.6 percent by value of the $584.3 million generated by all trophy lots auctioned in Hong Kong through May 20 in each of the past six years.

The most expensive artwork sold in Hong Kong during the sample period since 2018 was also by Zhang Daqian, whose Landscape After Wang Ximeng (1947) brought HK$370.5 million ($47.2 million) at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April 2022. Between this earlier transaction and Pink Lotuses on Gold Screen, lots by Zhang accounted for more than half the value (52.7 percent) of the $150.5 million worth of fine artworks sold for more than $25 million each in Hong Kong through May 20 of the past six years.

Discussing trophy lots in Hong Kong also necessitates a word about the globalization of taste. Although three of the four lots sold in the city for more than $25 million each are by Asian artists (Chu Teh-Chun joins Zhang in this group), the second most expensive lot sold there to date during the sample period is a painting by an American artist: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Warrior (1982), which traded for HK$323.6 million ($41.7 million) in a single-lot evening sale at Christie’s Hong Kong in March 2021. Deepening the nuance is the fact that Warrior was won by New York-based dealer Christophe van de Weghe, a reminder that not all lots sold in Hong Kong are bought by bidders based in Asia—and that the city’s growth as an auction market has been an international phenomenon in more ways than one.41

While the quantifiable details of minimum price guarantees, irrevocable bids, and other financial machinations remain opaque to outsiders, their effects are influential at the top of the fine-art auction market, where competition among houses to offer the most sought-after works intensified as prices escalated. Sales of lots above $10 million are therefore unusually indicative of significant new trends and longstanding stabilities alike, as the stakes have become so high that very little develops without both outsized demand and careful financial planning.

In this sense, one can have confidence that a market shift is real when it is reflected in the performance of trophy lots. This applies to such nascent phenomena as the emergence of Hong Kong and Paris as viable auction markets for works priced above $10 million, the sale of the first UltraContemporary trophy lot, and the sizable impact of single-owner evening sales on the marketing and sale of artworks in the highest price brackets.

The same is true of market dynamics that consistently repeat among trophy lots, including the dominance of the Impressionist and Modern genre, the overwhelming preference for New York as a sales venue, and the continuing rarity of works capable of selling for more than $50 million (let alone for more than $100 million), no matter what financing deals have been struck behind the scenes. The performance of trophy lots cannot tell observers everything about the state of the fine-art auction market, but it nevertheless speaks volumes.

Endnotes

Morgan Stanley Disclosures: This material was published in August 2023 and has been prepared for informational purposes only. Charts and graphs were published by Artnet News in the Mid-Year 2023 Artnet Intelligence Report. The information and data in the material has been obtained from sources outside of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (“Morgan Stanley”). Morgan Stanley makes no representations or guarantees as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or data from sources outside of Morgan Stanley.

This material is not investment advice, nor does it constitute a recommendation, offer or advice regarding the purchase and/or sale of any artwork. It has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. It is not a recommendation to purchase or sell artwork nor is it to be used to value any artwork. Investors must independently evaluate particular artwork, artwork investments and strategies, and should seek the advice of an appropriate third-party advisor for assistance in that regard as Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC, its affiliates, employees and Morgan Stanley Financial Advisors and Private Wealth Advisors (“Morgan Stanley”) do not provide advice on artwork nor provide tax or legal advice. Tax laws are complex and subject to change. Investors should consult their tax advisor for matters involving taxation and tax planning and their attorney for matters involving trusts and estate planning, charitable giving, philanthropic planning and other legal matters. Morgan Stanley does not assist with buying or selling art in any way and merely provides information to investors interested in learning more about the different types of art markets at a high level. Any investor interested in buying or selling art should consult with their own independent art advisor. This material may contain forward-looking statements and there can be no guarantee that they will come to pass.

Past performance is not a guarantee or indicative of future results.

Because of their narrow focus, sector investments tend to be more volatile than investments that diversify across many sectors and companies. Diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss in a declining financial market.

By providing links to third party websites or online publication(s) or article(s), Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (“Morgan Stanley” or “we”) is not implying an affiliation, sponsorship, endorsement, approval, investigation, verification with the third parties or that any monitoring is being done by Morgan Stanley of any information contained within the articles or websites. Morgan Stanley is not responsible for the information contained on the third party websites or your use of or inability to use such site, nor do we guarantee their accuracy and completeness. The terms, conditions, and privacy policy of any third party website may be different from those applicable to your use of any Morgan Stanley website.

The information and data provided by the third party websites or publications are as of the date when they were written and subject to change without notice.

This material may provide the addresses of, or contain hyperlinks to, websites. Except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, the firm has not reviewed the linked site. Equally, except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, the firm takes no responsibility for, and makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to, the data and information contained therein. Such address or hyperlink (including addresses or hyperlinks to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management) is provided solely for your convenience and information and the content of the linked site does not in any way form part of this document. Accessing such website or following such link through the material or the website of the firm shall be at your own risk and we shall have no liability arising out of, or in connection with, any such referenced website. Morgan Stanley Wealth Management is a business of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC.© 2023 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC 5839076 08/2023

Artnet Price Database From Michelangelo drawings to Warhol paintings, Le Corbusier chairs to Banksy prints, there are more than 14 million color-illustrated art auction records dating back to 1985 in the Artnet Price Database. The Artnet Price Database covers more than 1,800 auction houses and 385,000 artists, and every lot is vetted by Artnet’s team of multilingual specialists.

Artnet Disclosures: This Artnet Intelligence Report Mid-Year Review 2023 (“the Report”) was published by Artnet Worldwide Corporation (“Artnet”) in July 2023 and has been prepared for informational purposes only. Portions of the information and data in the Report have been obtained from sources outside of Artnet. Artnet makes no representations or guarantees as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or data in the Report, including from the sources outside of Artnet.

This material is not investment advice, nor does it constitute a recommendation, offer or advice regarding the purchase and/or sale of any artwork. It has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. It is not a recommendation to purchase or sell artwork nor is it to be used to value any artwork. Investors must independently evaluate particular artwork, artwork investments and strategies, and should seek the advice of an appropriate third-party advisor for assistance in that regard as the Report does not provide advice on artwork nor provide tax or legal advice. Tax laws are complex and subject to change. Investors should consult their tax advisor for matters involving taxation and tax planning and their attorney for matters involving trusts and estate planning, charitable giving, philanthropic planning and other legal matters. The Report does not assist with buying or selling art in any way and merely provides information to parties interested in learning more about the different types of art markets at a high level. Any investor interested in buying or selling art should consult with their own independent art advisor.

This material may contain forward-looking statements and there can be no guarantee that they will come to pass. Past performance is not a guarantee or indicative of future results.

Because of their narrow focus, sector investments tend to be more volatile than investments that diversify across many sectors and companies. Diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss in a declining financial market.

By providing links to third-party websites or online publication(s) or article(s) in this Report, Artnet is not implying an affiliation, sponsorship, endorsement, approval, investigation, or verification with any third parties or that any monitoring is being done by Artnet of any information contained within the articles or websites. Artnet is not responsible for the information contained on the third party websites or your use of or inability to use such site, nor do we guarantee their accuracy and completeness. The terms, conditions, and privacy policy of any third party website may be different from those applicable to your use of Artnet website.

The information and data provided by the third party websites or publications are as of the date when they were written and subject to change without notice.

This material may provide the addresses of, or contain hyperlinks to, websites. Except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Artnet, Artnet takes no responsibility for, and makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to, the data and information contained therein. Such address or hyperlink (including addresses or hyperlinks to website material of Artnet) is provided solely for your convenience and information and the content of the linked site does not in any way form part of this document. Accessing such website or following such link through the material or the website of the firm shall be at your own risk and we shall have no liability arising out of, or in connection with, any such referenced website.