Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, the past isn’t through with us…

The Duveen Agenda

Few things help put the present-day art market in perspective more keenly than studying key figures from the art market’s past. After reading S.N. Behrman’s biography of the bravura early 20th century art dealer Joseph Duveen over the past few weeks, I’m struck by the ways that a few of Duveen’s signature strategies show what has changed and what has stayed eerily similar about the trade in the 84 years since his death. The split is instructive. It shows that while some key aspects of any era’s art sales are grounded in mutable market conditions, much of it comes down to human psychology, which is all but guaranteed to endure not just from decade to decade but from century to century.

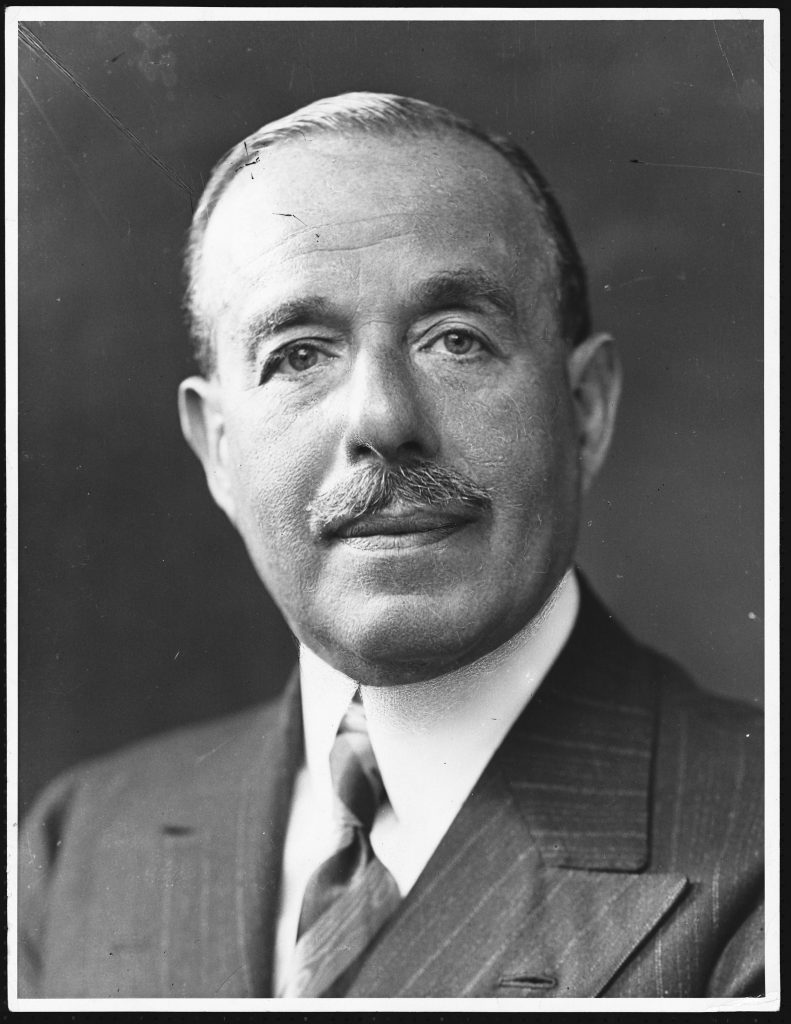

Who was Joseph Duveen? The question enlivened not only Behrman’s 1951 book (which is titled simply Duveen) but several others written to chronicle his life and career in the family business of selling increasingly fine things to increasingly fine people. In just two generations, the Duveen patriarchs progressed from dealing Delft tiles and furniture to window shoppers at an overstuffed storefront in the British port city of Hull, to brokering the sales of the most prized artworks on the planet to British royalty and the American robber-barons whose names still adorn some of the most august cultural institutions in the U.S.

Although Duveen’s father, Joseph Joel Duveen, and his uncle, Henry Duveen, deserve real credit for the rise of the family business, neither of them ever so much as dabbled in selling paintings. It was their son and nephew who pushed the Duveens headlong into the market for fine artworks. After his father and uncle died, Joseph took control of the family business and supercharged it into immortality, becoming the primary (if not the exclusive) dealer to the steel magnate Henry Clay Frick, Arabella Huntington (who, in an unorthodox turn, married both the railroad tycoon Collis P. Huntington and, after his death, his nephew and successor, Henry E. Huntington, founder of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens), and the banker and industrialist Andrew W. Mellon, to name just a few.

Recounting how Duveen did this is where the real fun begins. He created an international network of informants by doling out cash and kind words to the butlers, valets, housekeepers, ship crewmen, and other support staff to as many of the world’s wealthiest individuals as he could manage. He accused rivals of selling forgeries that he knew to be genuine purely because of the damage it would do to their client relations, even if it meant Duveen himself would be dragged into court with a losing case. He sometimes bought works that he believed were beneath his collectors (including then-contemporary pieces by the likes of Monet) for the express purpose of burying them in his gallery’s basement, minimizing the odds that his clients would ever see and potentially thrill to anything other than his Old Masters.

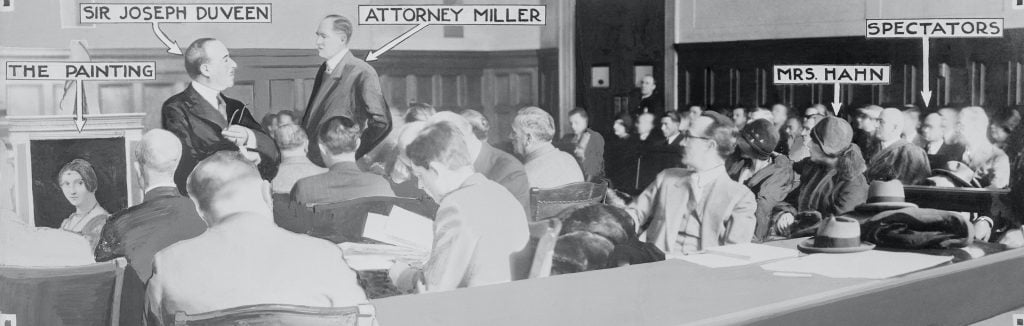

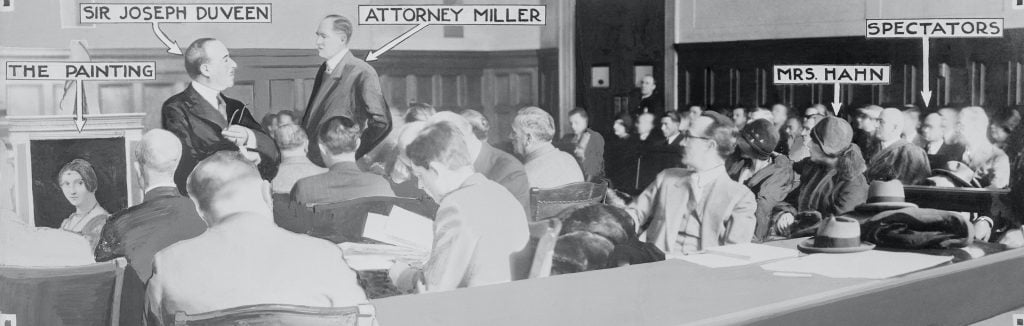

A 1929 courtroom illustration from the slander lawsuit brought against Joseph Duveen by Mrs. Andree Lardoux Hahn, whose sale of a purported Leonardo da Vinci painting to the Kansas City Art Museum was cancelled after Duveen cast doubt on its authenticity. Image credit: Bettman via Getty Images.

In fact, one of Duveen’s signatures was to channel this last tactic into an even more audacious form. It was nothing short of a monopoly mindset. Here’s Behrman on this point:

Professor C.M. Bowra of Oxford has said that Duveen was “the most symbolic figure of the twenties.” Certainly Duveen was a man of his time. It was a time of monopoly, and Duveen outmonopolized the monopolists who were among his biggest clients. In some people, the impulse to own everything appears to be congenital. Beyond the first victories, the horizons widen; they have to control not only the main stream but its tributaries. The impulse becomes a drive that demands the extermination not only of rivals but of potential rivals—a refusal to allow them to live, or even to be born. This temperament is not confined to businessmen. Some artists, scholars, and professional philosophers have it, and even, frozen in the dicta of ideology, some humanitarians; once you’ve palmed truth, it becomes logical to destroy those who don’t share it… Duveen’s career was dominated by this monopolistic drive.

First off, what a paragraph! More importantly, though, it’s important to understand how Duveen acted on this impulse. Strategically, tactically, and financially, he would go to extraordinary lengths to instill in his clients that they could only get the very best works through him, and only when he determined they were ready for them. He did this most often by buying everything he considered to be of real quality before anyone else could manage to do it. Hyper-aware thanks to his web of informants, he bought works privately that his competitors didn’t even know were on the market. He bought pieces at auction, winning bidding war after bidding war. He bought entire collections in bulk even when he was only interested in a small subset of the inventory.

Duveen worked for and against himself on this front by doing one thing over and over throughout his career: paying the highest prices he possibly could. Although Duveen had been generating sales and raising hell in equally notable proportions within the family business since several years earlier, Behrman contends that Duveen’s true introduction to art dealing came in 1901, when he bought his first painting, John Hoppner’s Lady Louisa Manners, for what was then the highest price ever paid for an artwork at a British auction: $70,250. He broke through that ceiling again and again over the next 38 years, and he did so entirely by design.

Most telling of all, Duveen was known to bid things up even when he was only competing against himself. Early in the book, Behrman recounts how he once asked a minor noble to name her price for a particular artwork, then balked at how low the number was when she complied. He only agreed to buy the work for a multiple of her price.

This might sound like idiocy. In reality, it was cunning. Among Duveen’s many hall of fame quotes about art dealing, none is more memorable to me than “When you pay high for the priceless, you’re getting it cheap.” This would scan as self-aggrandizing if not for the fact that he managed to get the richest people on the planet to believe it. Here’s Behrman again:

How did it come about that the great money men of that era gradually came to accept Duveen’s simple, unworldly view that art was more important than money? One theory is that Duveen had inculcated into them that art was priceless and that when you pay for the infinite with the finite, you are indeed getting it for a bargain. Perhaps it was for this reason that they felt better when they paid a lot. It gave them the assurance of acquiring genuineness, rarity, uniqueness.

Behrman follows this assertion with another art market anecdote from the Gilded Age, this time concerning second-generation American Joseph Widener, the heir to a trolley fortune and one of the eventual founding benefactors of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.:

A lesser dealer had a Rossellino bust for which he had paid $22,000. Joseph E. Widener went in to look at it. The dealer needed money and offered it for $25,000, thinking to tempt Widener into a quick purchase. The moderateness of the price was fatal. “Find me a better one,” Widener said. Duveen would have asked a quarter of a million, and got it.

It’s possible that no one in art-dealing history has weaponized high prices as deftly as Duveen. It wasn’t just that he found a way to finance such knee-buckling deals for individual artworks and entire collections; it was that he marketed his spending so that everyone with at least a passing interest would associate his name with the most valuable artwork on earth. Duveen even regularly tantalized the American press into publishing not only what his most recent major acquisition abroad was but how much it had cost him to get it––a fact that I can’t wait to mention to the next living dealer who scolds me for being gauche enough to ask about prices at an art fair.

Your columnist’s copy of S.N. Behrman’s Duveen. Photo by Tim Schneider.

It’s between Duveen’s hunger for monopoly and his genius for price psychology that we can triangulate the present-day art market. Although the trade is still a niche one in 2023, its scale looks galactic compared to the early 20th century.

Duveen’s central insight at the time was that almost no one with means in the U.S. was using those means to buy great artwork, a market inefficiency memorialized in his quip, “Europe has a great deal of art, and America has a great deal of money.” Implied in this matter-of-fact statement is that there was almost no one else who had recognized the potential value of correcting the mismatch. (I say “almost” because the only rival mentioned multiple times in Behrman’s book is Knoedler & Co., and in Behrman’s telling, Duveen was nearly undefeated against them.) Even the most jaded observer of the 21st century art trade has to admit that we’re well past a point where a single dealer could corner the market on a budding national superpower.

Duveen’s ambitions were also aided by the fact that there was only one genre and region of artwork considered worth paying top dollar for: European Old Masters. In comparison, it sounds like a utopia of choice to have five global mega-galleries and dozens of slightly lesser blue-chip dealers promoting an international array of living artists and estates with equal fervor, to say nothing of the auction houses and private sellers reaching deeper into the past for more high-end opportunities.

That said, Duveen’s insight about the mesmeric quality of a sky-high price on wealthy buyers is evergreen, at least when it comes to artwork and other subjective luxuries. Just as people tend to think cheap wine tastes markedly better if they’re told it’s more expensive, they also tend to think that artwork looks better (and has more meaning) if they know it was extremely costly. Despite all the scholarship and connoisseurship available, at some level we’re all just making arguments to back up our innate preferences within categories where there are no verifiable measures of quality. In this land of intuition and guesswork, price is still a signal that nearly everyone responds to in the same way. We can’t help it. It’s just the way our lizard brains are wired. And it won’t be any different in 2201 than it was in 1901, when Duveen set his first auction record.

This doesn’t mean that every rising art dealer can or should slap a million-dollar price tag on every piece in their inventory. It doesn’t even mean that they can or should pay high for the priceless—even if, like Duveen, a combination of favorable circumstance and wily maneuvering has put them in a position to secure the financing. But it is a reminder that, for a certain class of buyer looking for either incredible luxury or a taste of transcendence, it’s wrong to say that price means nothing. In fact, it means everything.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: we’re always juggling what’s changing and what’s staying the same. But the only chance to do it well is to be honest with ourselves about which is which.