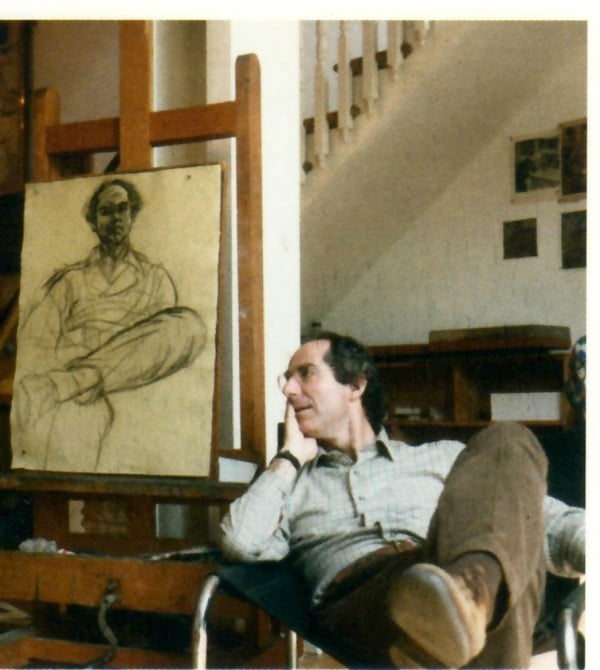

Philip Roth with portrait by Kitaj.

Image: Courtesy of Stephen Ongpin Gallery

——

The Good, Bad and (Very) Ugly of Frieze Week

Picking up from the last piece where my art-minded shrink was more interested in my market than my well-being, I subsequently texted him to halt further sessions—his response was, “I am at Frieze right now but no problem, my door is always open.” To this, I replied, “So is mine if you want to discuss your art issues.”

I’ve now had a physician/collector with an art-infused office discussing Joe Bradley’s latest work (on which, more to follow) while probing my prostate; a mechanic to whom I offloaded my old auction catalogues and who is now making art; and an acupuncturist who asked me to forward an image of the Amedeo Modigliani sculpture I am in the midst of selling (from the love of art for a change), before proceeding to mercilessly poke me full of needles while burning incense into my back (all perfect prep before attending London’s Frieze week). If the 1967 film The Graduate were remade, the word that would replace “plastics” as the nugget of career counseling would be “art.”

Donald Judd, Untitled (DSS 319) (1973).

Image: Courtesy of Christophe Van de Weghe

University of Zurich Executive Masters in Art Market Studies

In the days before Frieze, I was in Zurich for the art market studies seminar I’ve been teaching for a few years at the University of Zurich, a program born of masterpiece-priced masterpieces. Prior to the start of the class, I met with a few bankers, which I was lucky to have the opportunity to do since these days, every time you try to conduct a transaction with HSBC, you are perceived as guilty of impropriety before given the chance to prove otherwise. So much for the unregulated art market. Bankers are the new art world power brokers, not for buying a lot—many are inherently risk averse–but because you can’t deposit or transfer money without a relationship that’s too close for comfort. As a group, they should be on artnet’s Top 200 Art Collectors for this reason alone.

I awoke the morning of the 4-hour lecture with a cold and laryngitis, unable to speak—a promising sign for all—but had to carry on with the show. On a cocktail of boiling water with honey (at a cost of 9 Swiss francs from my hotel room) and Paracetamol, I went from inaudible to possessed, fueled by passion and adrenaline and practically speaking in tongues—don’t ask.

My teaching is like my writing and conversation only more unhinged and uninhibited (if you can bear to imagine). And aside from setting a few off into sound REM sleep, teaching is very conducive to having my thoughts congeal around the dynamic, rapidly changing art world. And I feel compelled to reveal the minutiae that no one will teach and write about: the good, the bad, and the ugly of the art market. It couldn’t have been that terrible: a young student offered me two significant Picassos for sale afterwards for upwards of $150 million and, though I was previously aware of both, I’d give her an A+ for taking the subject to heart.

A Damien Hirst colour chart.

Image: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Private Museums: The New Private Banks

It all appropriately enough began for Damien Hirst back in 1988 at the group exhibition that he curated entitled “Freeze” consisting of his Goldsmiths art school friends. Through sheer force of will and a very British pull-yourself-up-by-the bootstraps-mentality, he made a name for himself as a cultural impresario. A lot has happened since, and much has stayed the same—only grander, to the tune of $38 million in cash. Hirst has just opened his ambitious private London museum, the Newport Street Gallery, introducing a fluid market-affirming and -moving, not-for-profit-institutional-commercial hybrid. He’s out Saatchi-ed Saatchi and Gagosian combined.

I wonder if the artists that Rembrandt was so fond of championing and collecting, installed in what was (literally) the biggest private house in Amsterdam, went up in value as a result—until he lost everything, that is. Is Hirst the very first artist to set up an apparatus with the added allure of increasing the markets for the works he so avidly collects in his Murderme collection (the only name that’s worse is “Victim,” the uplifting tag of the charity he founded)?

Case in point, John Hoyland (1934-2011) the opening exhibit, a regional UK abstractionist of which Hirst is the owner of more than 60 canvases—he’s surely the biggest collector. 30, more or less, were on view in the imposing space before a friend on the inside of the Hirst machine bought a few for peanuts at auction. Guess what? Hoyland has been picked up by Pace Gallery and my pal is certain to cash in as a result. It’s only a matter of time before Hirst himself offers some up at Sotheby’s, his auction house of choice, which he may need to do being that a heart-shaped butterfly work, which previously sold for more than £600,000 in 2011, fetched under £400,000 at Christie’s London evening sale last week. By the way, in the museum, Hirst has declared he will not showcase his own works (there are plenty still clamoring to do that). However, erupting out of the Trojan horse is the on-message gift shop mostly filled with tchotchkes. No free lunch at the free museum, but it’s a nice gesture all the same.

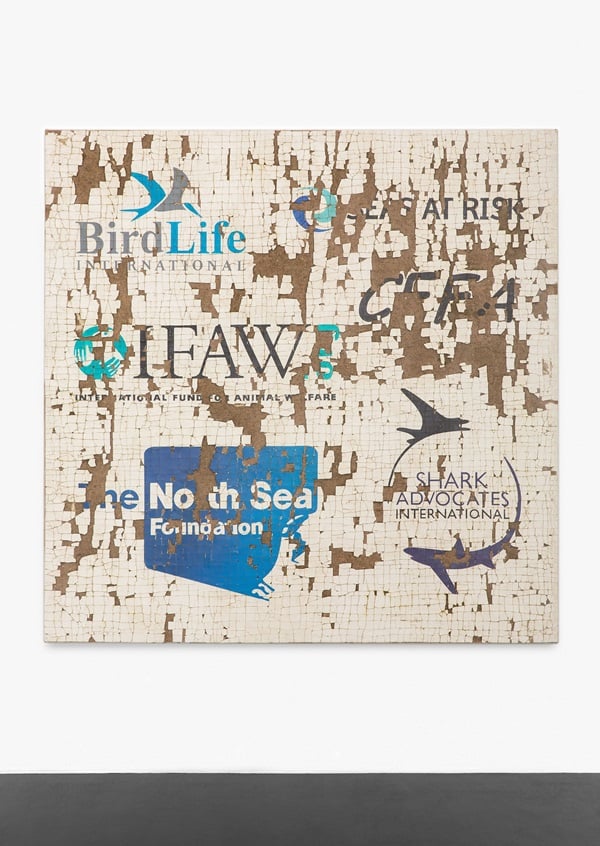

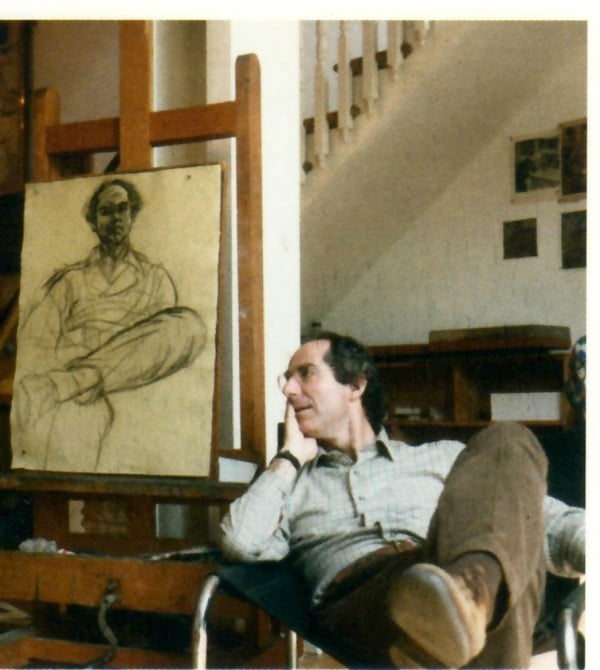

Mark Flood, Shark Advocates (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the Peres Projects

You see, private museums are the new private banks. Bloomberg recently reported that Eli Broad was bullish about the art market: no shit! He just opened his very own self-funded $140 million space in Los Angeles to house his $1 billion (at the very least) collection.

There should be a money-spent-on-private-museums economic indicator, the PMM: private museum money, to reflect the overall sentiment. In return for going public, they get tax and insurance breaks, all the while enhancing values through exposure and self-endorsement. Private museums are akin to the private banks of the Safras and Rothschilds of the distant past, and may soon evolve into the equivalent of multi-family art museum/storage facilities, through which buyers pool their resources to control and reduce shipping, conservation, and buying and selling costs. If it all sounds a bit onanistic, ask any of the Rubells.

Frieze and Frieze Masters

Some time ago, my intrepid informer, Deep Pockets (see Part II), and I decided to spend the whole of the Frieze openings suited, booted, and stuffed into stuffy Harry’s Bar engrossed in a 1970’s-style liquid lunch of red wine. After my Zurich teaching extravaganza, for the first time in ages I couldn’t bear to look at art. I was tempted to read of the top ten booths online and skip the fair, but it would have been wrong for me (if not you, too). Besides, though boring and sadly domesticated this year, there’s always loads of info to glean. I won’t mention the alarming call from my wife regarding the three folks who turned up at my house (which I didn’t leave for a few days) for my 3pm appointment. But it was rather too late by then in relation to my lack of timeliness and sobriety to make it to the opening.

Avoiding the Frieze openings onslaught was a godsend, like missing the Black Friday sales that launch the Christmas shopping season; and in any event, the people in town, from museum directors, curators and heavy hitters far outweigh the significance of any art on view. In this business you collect collectors as much as pictures.

When I finally mustered the appetite to visit on the last day, which I did with my 16 year-old, it was more relaxed and well worth it, though tangibly without revelation. Gabriel nailed it when he said, “I was hoping to see something sick (translation: good)…but I didn’t, not a thing.” I overheard someone describing the fair as “hot,” as in boiling and stifling, which it was aplenty, like a clock-less, windowless casino.

Brent Wadden, TBT (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the Peres Projects

Jerry Saltz was in full character chattering away on social media from the comfort if his iPhone in New York, moaning about the blights that are fairs and auctions (even he must find this shtick yawn-worthy by now). Yet as much as I don’t particularly care for the snooty elitism of the Frieze fair proprietors, it’s yet another glorious accumulation of art at a given point in time. It’s enough to visit if you can for the sheer quantity of art. So, why not?

On the Frieze sales floors were Harold Ancart’s (b. 1980) colorful paintings on paper of volcanic landscapes based on a Tintin book cover at Brussels- and Brooklyn-based Clearing gallery, And clearing is what they did. With the works priced at about $40,000 each, you could get in line if you wanted a piece by this Belgian Mark Grotjahn (b. 1968), but even then, you would have been better off forgetting about it. Gallery lists for the likes of Jonas Wood, Ella Kruglyanskaya—I unfortunately sold mine by the time I learned to say her name—Dana Schutz and Math Bass are strictly categorized by a social and financial pecking order rather than anything else.

Hirst took time off from his extracurricular activities (including master planning a UK eco-city, for real) to exhibit his stillborn commercial logo paintings and a Richter-esque color chart work for about $1.2 million (sold!), a poor example of a turgid trope. What was admirable was the Chinese text on the painting delineating the colors of the spectrum, a case of the artist trying to speak directly to a market. Hirst’s enterprise seemingly conducts focus groups to pinpoint unexploited lands to drop (spots) into, made to measure in your indigenous tongue.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled(1981).

Image: Courtesy of Christophe Van de Weghe

Few gallery owners were seen manning their booths on the last day, though an exception was the always lively and nice Javier Peres of Peres Projects in Berlin. Peres proceeded to give me the (fairly unprecedented—for him) hard sell for a Brent Wadden knit work at $50,000 and a Mark Flood painting at $60,000, for both of which, only a year ago, he would have merely added me to the list (far down, no doubt). The market for young art goes from all to nothing, and we are now firmly planted in the land of nothing.

At Frieze Masters were the works of Gutai master Kazuo Shiraga (1924-2008) at Dominique Levy, whose prices seem to have gone up as high as they have abruptly. Shiraga is the artist who played footsie with his canvases—literally had himself strapped into a harness and employed his feet to paint. I think I might prefer the hand of the apprentice to the feet of the master—just playing—I guess I’m a prig for painting. But the prices weren’t very playful: €3.2 million for a work made in 1961 and $5.5 million for another from 1959, all big numbers that are only a recent phenomenon; whether they last is another game. And both were still available at the time of this writing, one, albeit, on hold.

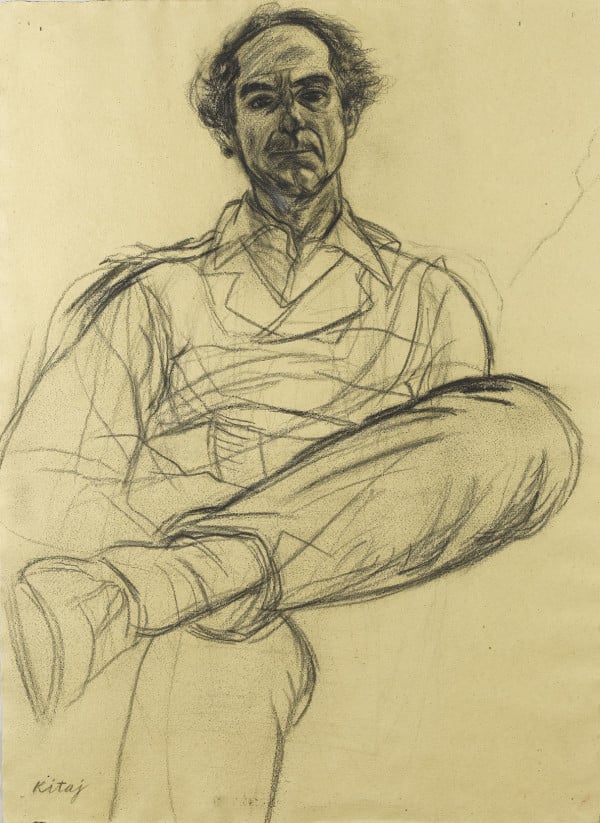

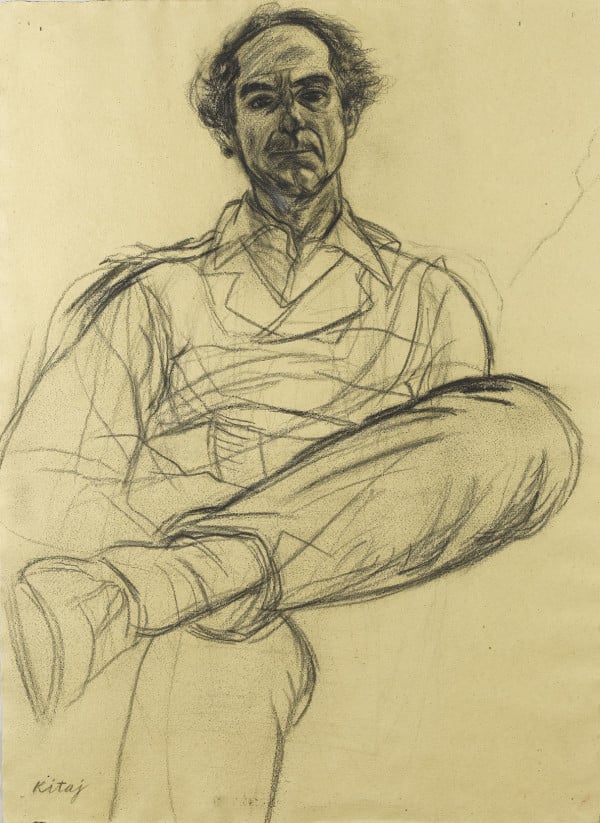

Stephen Ongpin of London is a man after my own heart. A dealer in works on paper from artists spanning centuries (I began my career dealing classic contemporary prints and drawings—not that I’d know a Holbein from a Holiday Inn painting), Ongpin is a dyed in the wool (not Christopher but more on him later) art lover who sells pieces of connoisseurship as much as art. As he stated to me, draftsmanship flows throughout history and influences artists from generation to generation (though you’d be hard pressed to find much of it nowadays) so why not connect the dots? At his booth was an R.B. Kitaj charcoal portrait of the author Philip Roth priced at £150k; though the work went unsold, Ongpin’s passion and knowledge of the work in his gallery was self-evident.

R.B. Kitaj, Portrait of Philip Roth.

Image: Courtesy of Stephen Ongpin Fine Art

Another master dealer at the Masters was Richard Nagy, which featured a breathtakingly stunning booth with German Expressionist drawings hung cheek by jowl on and around reproduction pieces by the architect and designer Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956). When I asked for a press release about the exquisite installation, Nagy snapped, “It’s only about the art.” Hey, wait a minute, you went to the effort and expense of creating something special. Why would you be surprised that it evokes a legitimate response?

The prize for the most creative riposte to a query though goes to Christophe van de Weghe, a talented veteran of secondary land, regarding a work by Jean-Michel Basquiat. When I asked if the 1981 oilstick-on-composition-board work priced at $1.4 million was signed, I was told, “Yes with his footprint.” Touché.

Also pretty seductively alluring was the untitled curved copper wall piece by Donald Judd, which, at $2.8 million, seemed cheap somehow (that’s the relativity of the art world). And, the best overheard line at the fair came from the Gagosian-ite who was flummoxed by the one-person show at their Masters booth (for some galleries, one Frieze was not enough) of the perennially undervalued and underappreciated Richard Artschwager. He could no sooner identity who the artist was than he could what the artist did.

In the end, it was all good—from an informational and visual perspective, it was a lot to take in and digest. But stay tuned for my auction and FIAC recap, it’s even hairier. There’s no shortage of those who will differ, but it’s an undoubtedly good time to be in art.