By almost any measure, Fort Gansevoort, the gallery that husband-and-wife duo Adam Shopkorn and Carolyn Tate Angel founded in Manhattan in 2015, has been on a winning streak.

In recent years, its artists have entered dozens of museum collections, including those of the Museum of Modern Art and the Met in New York. In late 2019, it opened a second location in Los Angeles, and in 2020, three of its shows graced various best-of-the-year lists, including one by critic Jerry Saltz, who praised the gallery’s “whole presence and program.”

What resonates for institutions, critics, and collectors alike, according to Trevor Schoonmaker, director of the Nasher Museum at Duke University, is Fort Gansevoort’s focus on talents who live and work outside the usual parameters of the art world.

“Adam really has an eye for artists who have been lesser known or underrepresented,” Schoonmaker told Artnet News. Through the gallery, the Nasher recently acquired a painting by the late Cleveland-based, self-taught artist Michelangelo Lovelace, as well as a work of pastel on paper by the Oklahoma City-based artist Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds.

Installation view, Fort Gansevoort in Los Angeles. Photo: Courtesy of Zoya Cherkassky and Fort Gansevoort.

Shopkorn, 43, had been forthright in introducing his artists to the museum, Schoonmaker recalled. “He came to us understanding our commitment to centering artists of color—our own small way of trying to upset the canon.”

Representing artists who’ve had little commercial exposure, many of whom are Black, Indigenous, and working into their twilight years, Shopkorn similarly brands Fort Gansevoort as an outsider to the status quo.

“I’m proud that I never worked at a gallery,” he said. (Nor has Angel, a veteran fashion editor.) But Shopkorn is no stranger to the art market. A New York native and son of a hedge-fund founder, he started collecting art at the tender age of 22. (His first purchase was a Stan Douglas photograph from David Zwirner.) While getting his MBA at NYU’s Stern School of Business, he began art advising on the side.

Along the way, he built a formidable list of blue-chip contacts, an unquestionable ingredient in Fort Gansevoort’s winning formula. Structural privilege aside, Shopkorn also owes his success to refining an unusual approach: he seeks out artists in unexpected places; strategically cultivates relationships with smaller museums; sidesteps formalities by entering through side doors; and appears to have little fear of risk.

“I like to go further out in my boat than all the other boats, and I like to fish by myself,” he told Artnet News, before adding, “I’m not equating artists to fish—my point is that there are so many amazing artists in the world, and I want to find these artists on my own.”

Through his own trial and error, he’s carved out a niche for Fort Gansevoort that strikes the art world as playing by its own rules—while still appealing to its current tastes.

Carolyn Tate Angel. Photo: Fort Gansevoort.

Not How to Look, But Where

Shopkorn and Angel operate Fort Gansevoort out of a three-story townhouse in Manhattan’s meatpacking district, employing a publicist and an in-house staff of three. He generally dislikes doing art fairs and group shows, and prefers to scout new talent on social media, as opposed to Ivy League MFA programs.

“Great artists come out of those schools, but that’s not what I’m looking for,” he said. “I like working with real people—I’m looking for authenticity, for gross oversight, for artists with something to say.”

Describing himself as both impatient and persistent, the gallerist admits to frequently parachuting into artists’ lives. He first saw the work of Israeli-based artist Zoya Cherkassky—cartoon-like depictions of her 1980s childhood in Communist Ukraine—in an Instagram post by the Richmond, Virginia-based curator Amber Esseiva. “I became obsessed,” he said, and boarded a plane to Jerusalem to meet her within “less than 48 hours.”

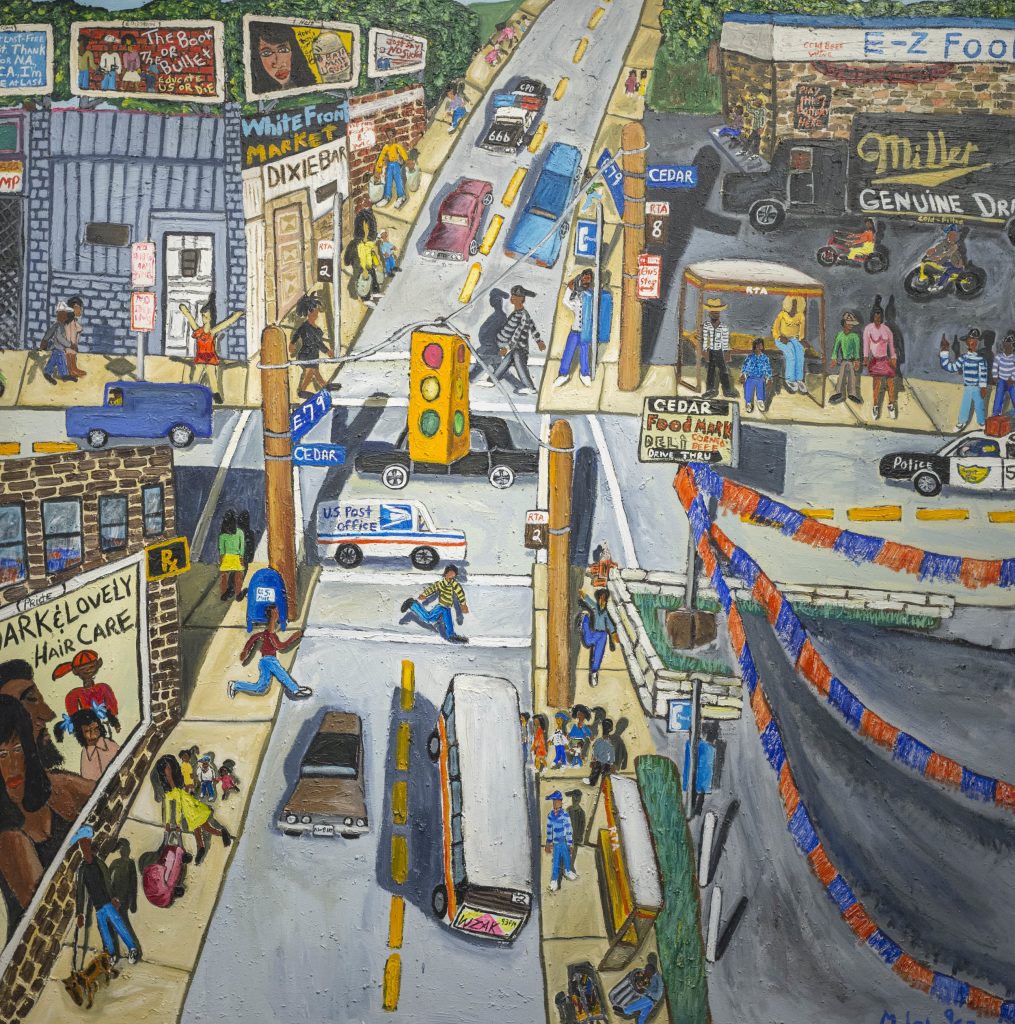

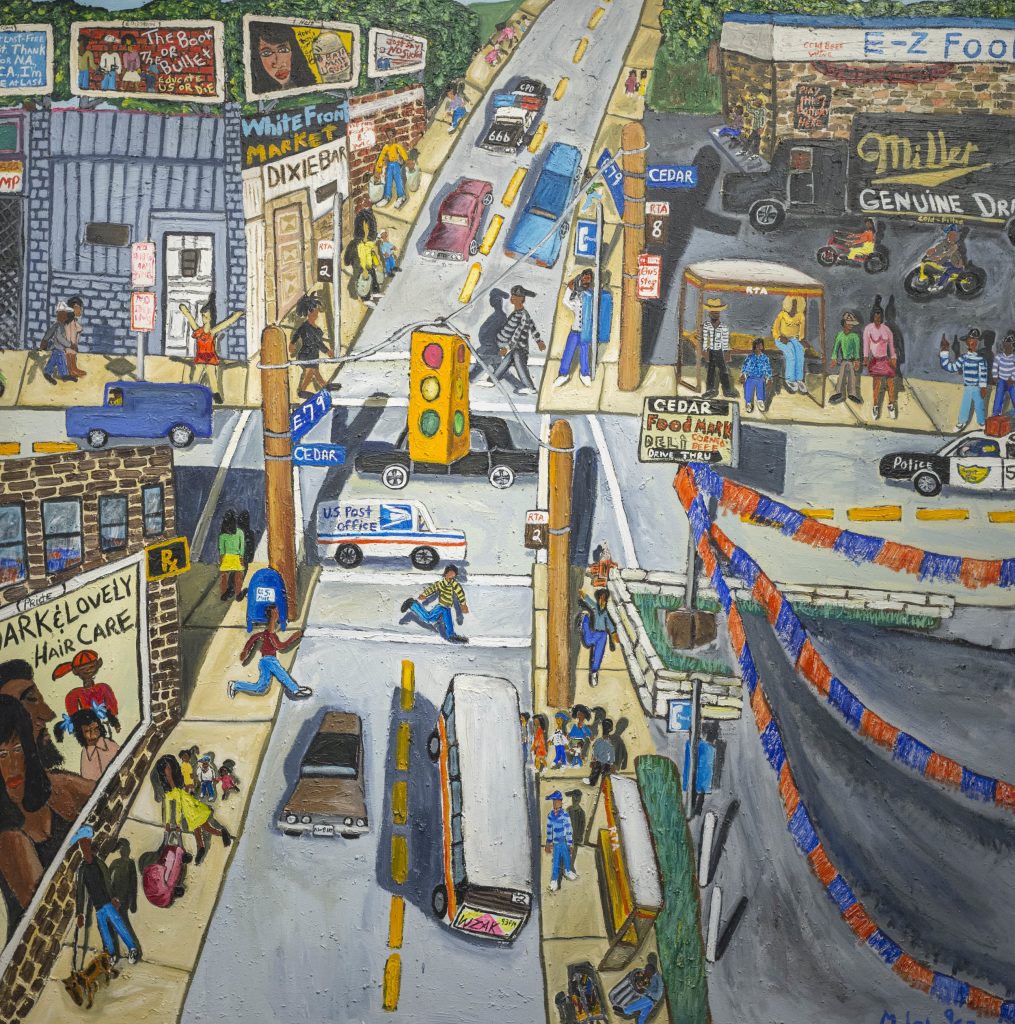

In late 2017, Shopkorn cold-called the late Michelangelo Lovelace to request a studio visit, having spotted one of his paintings while perusing the Cleveland Art Museum’s website (a normal activity for a Saturday night). Lovelace reluctantly agreed, but before allowing Shopkorn to enter his home, asked to see some I.D.

“Yeah, Michael carded him—he didn’t have a lot of trust,” Shirley Lovelace, Michelangelo’s wife of 35 years, recalled with a chuckle. For almost 40 years, Lovelace had captured Cleveland’s racial and economic tensions in acrylic cityscapes while supporting his family as a nurse’s aid. Interested parties courted him over the years, but never fully made good on their promises to further his career. Sometimes, they disappeared with his work and never paid.

Michelangelo Lovelace, At the Intersection of East 79th and Old Cedar (1997). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Shopkorn was different. After presenting the proper I.D., he looked through Lovelace’s vast trove of work and began selling almost immediately. “He must know the right people,” Shirley said.

In 2018, Fort Gansevoort mounted a sold-out exhibition of about two dozen of Lovelace’s paintings, priced between $25,000 and $50,000. The couple, who were flown out for the opening, attended Shopkorn’s surprise 40th birthday in the gallery the next night, where many of the guests bought works.

The artist Hank Willis Thomas, an occasional co-curator of Fort Gansevoort shows, introduced Lovelace’s work to Alicia Keys. Pieces by the artist were acquired by Kansas City’s Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, the Figge in Davenport, Iowa, and several other institutions large and small. Critics at the New Yorker, the New York Times, and Artforum showered him with praise.

Shopkorn became visibly emotional while talking about Lovelace; in April, at age 60, the artist died of pancreatic cancer. As the gallerist recalled what drew him to the work, his description was devoid of artspeak.

“I feel like someone could write an incredibly smart, provocative essay about just the billboards in Michelangelo’s paintings,” Shopkorn said, noting the painter’s frequent use of text. For his part, “I’m like a sucker for ’90s hip hop. He was referencing Jay Z and Drake, and he was referencing the hood. That’s real to me.”

Installation view, Fort Gansevoort in New York City. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

An Insider’s Outsider

After graduating from business school in 2006, Shopkorn shuffled between creative gigs (art advising, producing a basketball documentary, organizing public art projects for a friend at the Morgans Hotel Group). Around 2015, Shopkorn noticed a vacant townhouse near Gansevoort Street with “brick walls like a fort,” and imagined turning it into an art space. Acquainted with the building’s owner through both his cousin and his wife, he was able to negotiate “a somewhat fair lease.”

“I didn’t want to be a traditional, purely commercial gallery,” Shopkorn said, and so Fort Gansevoort opened with a decidedly non-traditional business model. The initial iteration was branded as a cultural hub, complete with an industrial pit smoker in the backyard and a small takeout window for pulled pork and chicken sandwiches.

Early presentations included still lives by graffiti artist Ces, paintings by jazz musician Dickey Landry, and multimedia works by movie producers Benny and Josh Safdie, childhood friends of Shopkorn’s. As part of Fort Gansevoort’s high-concept retail boutique, there were also resident artisanal candymakers and organic perfumers.

“Right out of the gate,” Shopkorn conceded, “I knew I had made a number of mistakes.”

Confused visitors didn’t recognize Fort Gansevoort as a gallery, and an understaffed Shopkorn found himself cleaning up barbecue sauce after hours. Two years in, he changed course, getting rid of the retail arm and the barbecue pit, but keeping the townhouse and outsider mindset.

“You have to take a risk, and sometimes it doesn’t work,” he said, expressing no regret.

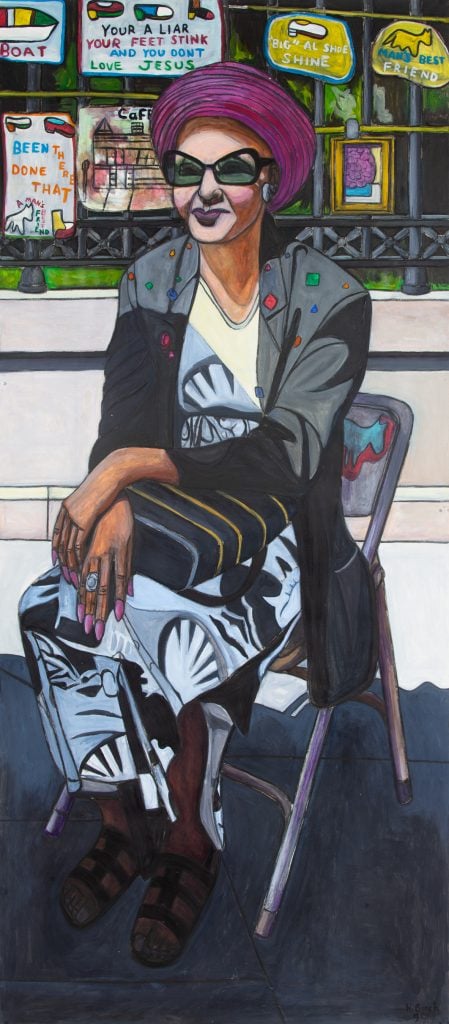

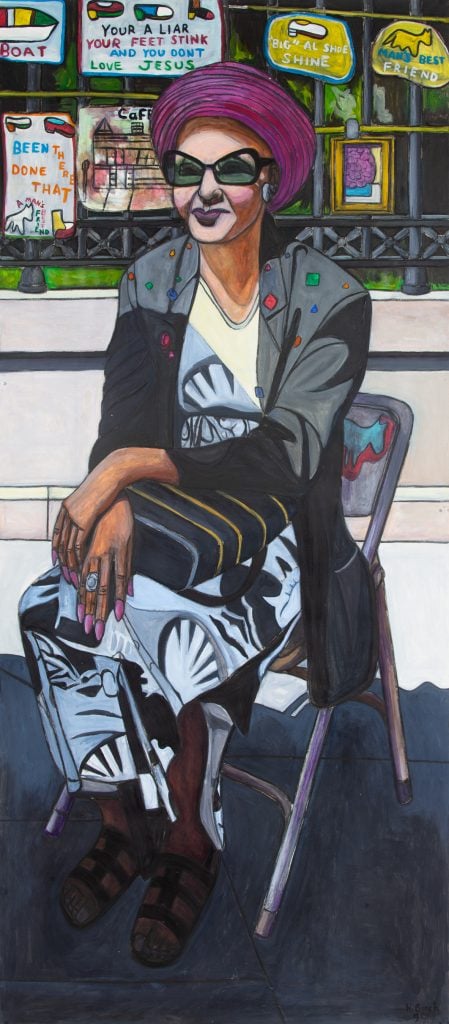

Willie Birch, Woman Sitting in Big Al’s Gallery (1999). Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Branding and Identity

Where early shows focused on the work of predominantly white men, Fort Gansevoort 2.0 found success in showing predominantly BIPOC artists making political, figurative work—78-year-old Willie Birch of New Orleans, for example, or Kaylene Whiskey of Australia’s Indulkana community. (Edgar Heap of Birds, one of the gallery’s biggest success stories, said he is no longer working with Fort Gansevoort, though he declined to comment further.)

Shopkorn’s change in approach coincided with the art market’s newfound interest in its own course correction, atonement for its historical exclusion of non-white artists.

Veteran collector and Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) trustee Eric G. Johnson, who recently gifted works by Fort Gansevoort artists to the Met, the Studio Museum, PAMM, and others, said he found the gallery’s outsider approach “compelling.”

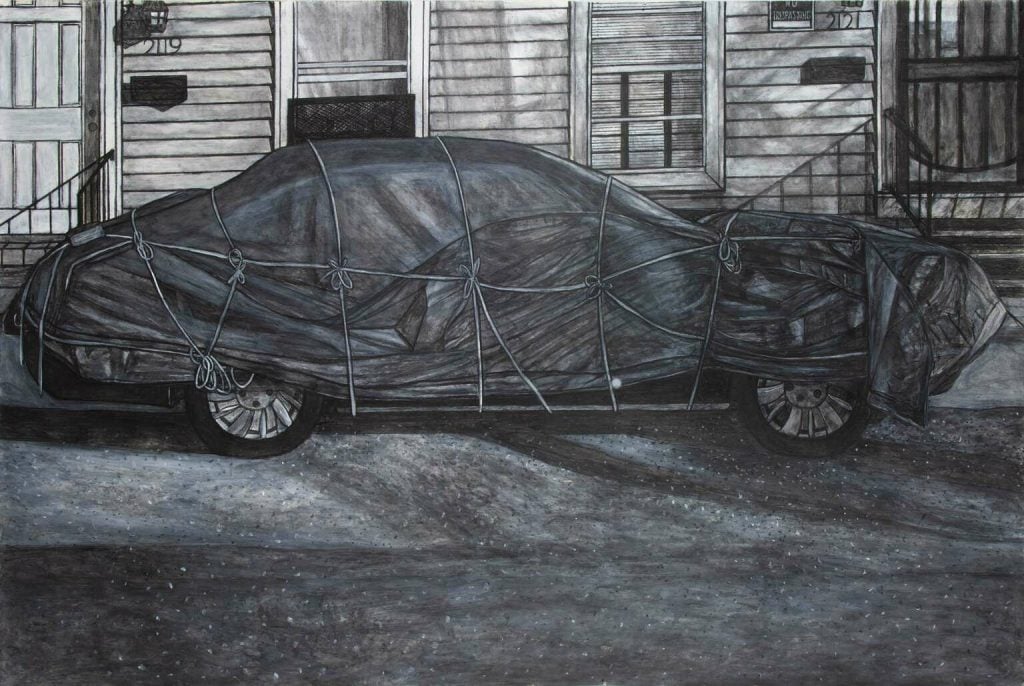

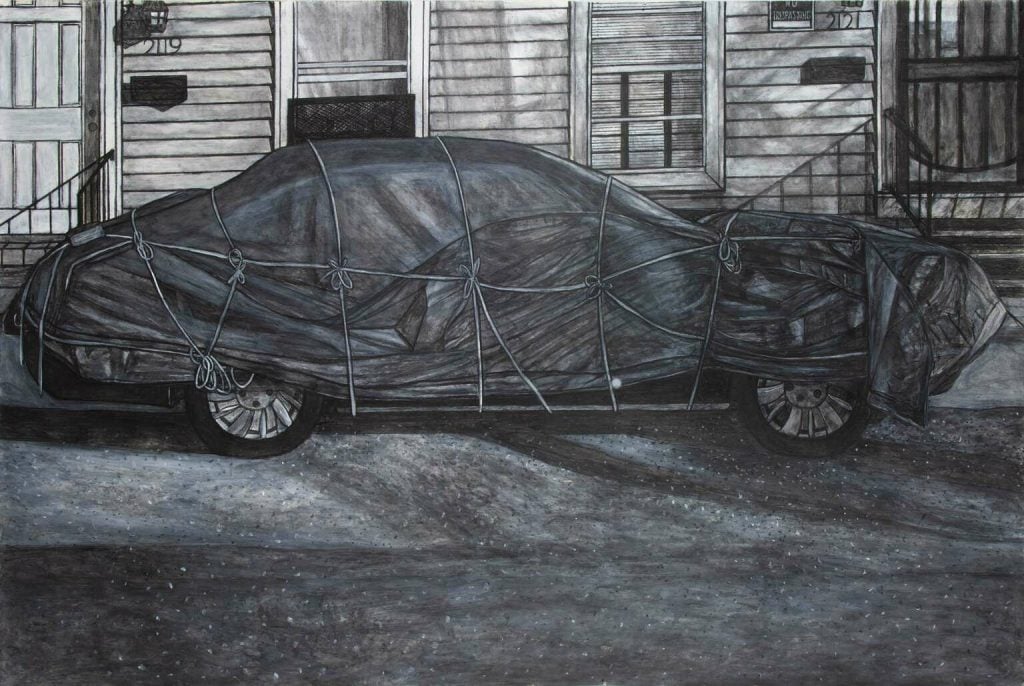

Willie Birch, Covering (2015). Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Dawn Williams Boyd, who joined the gallery late last year, is ambivalent about Black artists becoming “topical,” even “fashionable,” in the art world. “Because of BLM, lots and lots of Back visual artists and other kinds are being pushed to the fore,” she said. “I’m no fool—I don’t expect that to last,” she added, although for now, “I’m a happy camper.”

After more than 40 years of making her cloth paintings—textiles stitched into evocative political scenes—she was contacted by Shopkorn out of the blue in 2020 to consign work. To her surprise and delight, he offered a contract for representation six months later, and asked her what she wanted.

“I told Adam, I’m not making work for people who hoard art, or you have to be somebody to see them,” she said. “I just want ordinary people like me to pay their little money to go to a museum and see my work and say, ‘This speaks to me.’”

Shopkorn delivered, placing cloth paintings in the Met, the Birmingham Museum of Art, and several other institutions, with upcoming solo shows at Syracuse’s Everson Museum, Sarah Lawrence, and the University of Georgia.

For the artist, showing at universities is an opportunity to inspire young people. For Shopkorn, strong relationships with regional museums are “the crux of Fort Gansevoort. They don’t have to jump through as many hoops as these bigger institutions to make things happen.”

Dawn Williams Boyd, The Trump Era: Incarcerated (2019). Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

The Future of Fort Gansevoort

Today, as he continues to work directly with Sugar Lovelace, scanning Michelangelo’s archives and selling his work, Shopkorn feels he has lots left to do.

“I want a museum to have a big survey of his work, 60, 70 paintings,” he said. “And you could put Willie Birch’s paintings next to Alice Neel’s paintings, or Dawn Williams Boyd’s cloth paintings next to Faith Ringgold’s. It’s wildly important to me to give a platform to these undervalued, underrepresented artists. I’m working my ass off to build careers for them, to put them in front of the right people, to talk to more curators, and to keep doing the work that we’re doing.”

Dawn Williams Boyd, for one, is pleased. “I’m reaping the benefits of Adam doing a fabulous job, and he’s reaping the benefits of me doing a fabulous job,” she said. “It’s business.”

Looking ahead to the next 10 years, Shopkorn imagines a future where his program may look very different, where current artists have happily graduated to larger galleries, and Fort Gansevoort is matriculating a new class of completely different artists.

“I don’t believe in this idea of the big evil gallery stealing from the small gallery,” he said. “If I’m very confident with my ideas and my ability to identify talent, I have a strong conviction that there’s no shortage of great artists in the world. All you have to do is look.”