Market

The Back Room: The Inaugural Edition(!)

This week in the Back Room: Frieze NY in a flash, a divorce boom makes waves, a fractional art investment primer, and more—all in 7-minutes.

This week in the Back Room: Frieze NY in a flash, a divorce boom makes waves, a fractional art investment primer, and more—all in 7-minutes.

Tim Schneider

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy. The inaugural month’s editions are free, but you’ll have to become a member (and click the “subscribe” box during checkout) to receive it in June and beyond.

A fairgoer uses her phone in the cafe during the first day of Frieze art fair. (Photo by TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP via Getty Images)

It happened: an international array of art-market movers and shakers converged this week to make Frieze New York a reality. (In-person! At scale! In a convention center! Are you tired of this joke yet?) The early returns suggest sales and enthusiasm are bouncing back fast in the U.S.

“It’s not just New York—America is present,” said Hauser & Wirth president Marc Payot at Wednesday’s VIP opening. (He also claimed to have done 12 straight hours of meetings with visitors from Dallas, San Francisco, and elsewhere the day before, marking the first time in my life a humblebrag from a dealer has given me a sense of hope for civilization.)

Heavy hitters from all branches of the industry were present on day one: collectors Howard and Cindy Rachofsky, Don and Mera Rubell, Mike Bloomberg, and Agnes Gund; museum directors Thelma Golden and Richard Armstrong; Christie’s C.E.O. Guillaume Cerutti; and more.

Even NFT sensation Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) put in time at what he called his “first real art fair.” He told Katya Kazakina that “talks are happening” regarding a gallery show. From crypto to cryptic, this guy! Like he’s been in the art world forever…

As for the trade itself, I’ve never been so pleased to run out the cliche that first-day sales were strong, especially in the mid-five and six-figure range. However, sources said a slew of booths sold out pre-sale, including five new Dana Schutz paintings priced between $500,000 and $1 million at David Zwirner.

Other reported day one (or “day one”) transactions included:

● Louse Bourgeois, Blind Man’s Buff (1984) – “around $1 million” (Hauser + Wirth)

● George Condo, The Drifter (2021) – $800,000 (Hauser + Wirth)

● Hernan Bas, The Suspect (2021) – between $350,000 and $400,000 (Lehmann Maupin)

● Ha Chong-Hyun, two paintings – “in the range of” $200,000 to $300,000 each (Tina Kim)

● Cristina Canales’s paintings – “nearly sold out” from $17,000 to $53,000 each (Galeria Nara Roesler)

The opening of Frieze New York 2021 came off as close to a best-case version of the “new normal” as could have been hoped. Yes, health checks and masks were a drag. But much of the industry showed up, timed entry made the experience uncharacteristically pleasant, and sales were brisk. The virus situation makes European fairs a question mark, but Frieze’s success bodes well for the Armory Show and Independent’s return in September.

Happy Divorce! (Photo by Keith Beaty/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

A pandemic-driven divorce boom is shaking up the world of elite wealth—and it should keep the art market jumping well into 2023.

That’s the message in Katya Kazakina’s inaugural edition of The Art Detective, her weekly column sleuthing through the market’s best-kept secrets. (Another Artnet News Pro perk, folks.)

Some of the names parting ways and splitting collections are familiar: Bill and Melinda French Gates, Linda and Harry Macklowe, and even Sotheby’s private sales guru David Schrader, who just finished divvying up a 20-year collection with his ex-partner.

Appraisers are the first to benefit from the acrimony. Divorce-related valuations of fine art and collectibles are up 25 percent compared to just before lockdown, according to Winston Art Group’s Elizabeth Von Habsburg. The reason? You can’t finalize a divorce settlement without agreed-upon asset valuations.

Splitting amicably saves collecting couples money, too, and not just because they avoid paying trial lawyers. Quietly sorting out who gets what means soon-to-be-exes also avoid hefty capital-gains taxes that would come from selling to outsiders.

But if a divorcing couple can’t come to terms privately, they’ll be forced to liquidate at auction, meaning auction-house fees and sales taxes, too. The dueling can even extend to the salesroom. Lawyers agree spouses often wage bidding wars against one another, sometimes strictly to inflict pain—exemplified by one husband threatening to win a piece just so he could burn it on video.

Expect 12 to 36 months of art-market action from all this, according to Schrader. Between appraisals, settlement negotiations (or trials), and a pandemic-induced bottleneck in divorce court—to say nothing of the private sales and auctions—the trade is in for a different kind of COVID-related long haul.

A promotional image for Masterworks’s offering of shares in Andy Warhol’s 1 Colored Marilyn (Reversal Series) (1979). Courtesy of Masterworks.

Masterworks, the investment platform securitizing fractional shares in blue-chip paintings, is on a mission to become “the largest buyer in the market” according to founder Scott Lynn. After acquiring more than $100 million in paintings in 2020 alone, and attracting more than 140,000 users to date, the company’s Silicon Valley-style growth strategy is premised on the notion its shareholders can consistently beat the niche art trade through its Wall Street models, proprietary market analytics, and economies of scale.

But art-industry veterans questioned three elements of the Masterworks sales pitch:

● Fee Structure

Is it too much to charge a 10 percent fee inside the initial offering price, a 1.5 percent management fee yearly, and a 20 percent fee on the resale profit when a painting is finally dealt?

● In-House Data Accuracy

Has contemporary art at auction really posted bigger gains and softer losses than the S&P 500, global equities, and other assets since 1995? And is an index tracking repeat sales of U.S. homes really the best model for tracking changes in individual artists’ historical results under the hammer?

● Aggressive Growth

With plans to spend $300+ million on art by EOY—“typically” resulting in its acquiring new work every week—can Masterworks consistently buy low and sell high on top-quality paintings for the long run? Or will this torrid pace prove incompatible with the narrow supply and irregular market conditions of blue-chip art?

“Auction houses were knocking themselves out to get good pictures. I didn’t have any clients coming to me desperate to sell. If you spent $100 million in 2020, were you getting the best opportunities?”

– Megan Fox Kelly, president of the Association of Professional Art Advisors, on Masterworks’s shutdown-era buying spree.

Masterworks acts as a Rorschach test, even for finance-savvy collectors: Do you see great paintings as an asset whose value can be standardized, quantified, and diversified invisibly into a portfolio… or a highly specific, irregular good whose value must be experienced, not just traded? If the former, read the fine print. If the latter, ignore the whole enterprise.

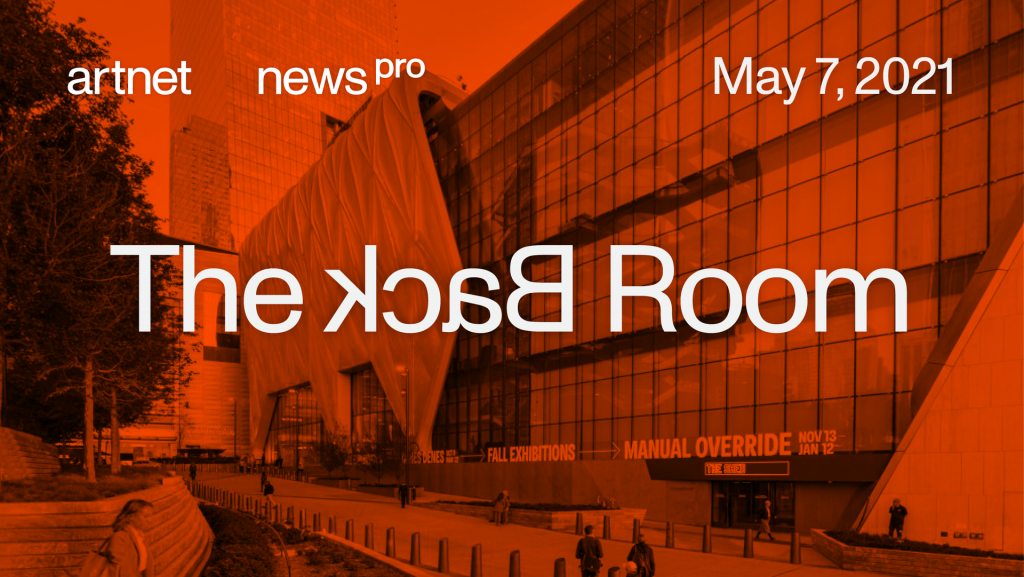

All data © Artnet Analytics 2021.

You read those dates right: global fine-art sales at auction this March ($1.1 billion) were more than one-fifth higher than in March 2019 ($940 million)—a full year before shutdown—according to the Artnet Price Database.

The biggest difference? Fifteen lots sold for $10 million or more this March, against only seven in March 2019.

Even on its own, the resurgence in trophy sales would have boded well for supply and demand at the house’s this spring. Add in the bonanza of choice pieces pushed onto the block by marital strife, and signals suggest May will be an epic bounce-back month for the auction market.

Smash the button below for more detailed analysis from Julia Halperin.

“Shortly after I arrived at [MOCA Los Angeles], Eli asked us to print out all of the museum’s financial records from the past several years. I delivered to Eli a two foot stack of accounting records. This would be his weekend reading. Eli was unique in combining this financial acumen with an enthusiasm for the latest artistic innovations.”

– Jeffrey Deitch remembering Eli Broad, whose death at age 87 was announced last weekend.

Ex-Sotheby’s dealmaker Adam Chinn will launch LiveArt Market, a peer-to-peer online sales platform powered by machine learning and extreme discretion, this month. (Wall Street Journal)

Aimed at cutting out the middleman for high-end sales, features will include…

● Free automated estimates via algorithms that crawl auction data

● Control over what data remains anonymous (including a work’s current owner)

● In-house provenance researchers and conservators

● Flat 10 percent buyer’s premium (vs. up to 25 percent at major auction houses)

Veteran collectors (surprise!) have almost no interest in NFTs. (New York Times)

Zona Maco was lively thanks to a focus on local galleries and restriction-free travel from Europe and the U.S. (Artnet News Pro)

Positive outlooks for economic growth and corporate profits have led investors to greet Joe Biden’s proposed tax hikes as follows: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. (New York Times)

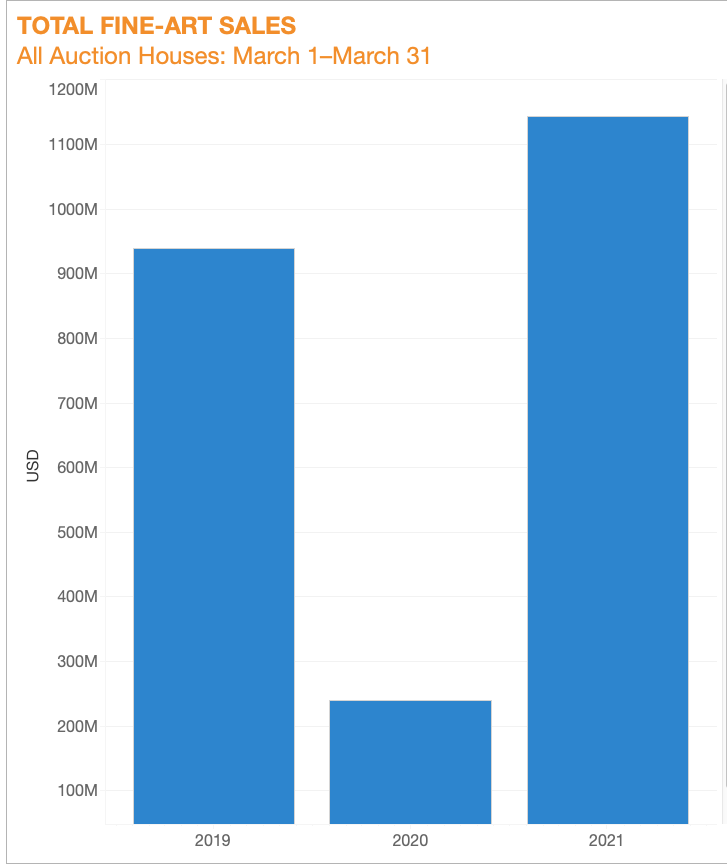

Roy Lichtenstein, Interior: Perfect Pitcher (1994). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd. 2021.

Date: 1994

Seller: Private Collection, New York*

Presale Estimate: $20 million to $30 million

Selling at: Christie’s 20th-Century Evening Sale, New York

Sale Date: Tuesday, May 18

Clocking in above 10 feet by 16 feet, this vibrant example of Lichtenstein’s “Interiors” series epitomizes the value of a sterling provenance. Only the artist himself and his estate held the painting before its current unlisted owner… who sources claim is none other than Larry Gagosian. (A Gagosian spokesperson denied the claim.) What we do know is that the painting is backed by a third-party guarantee, so no matter what happens on auction night, someone will walk away with this bravura painting—and I’ll bet you that someone owns exactly zero NFTs.