The Gray Market

Why the Art Market Is Colliding With Investors’ Biggest, Weirdest New Fixation (and No, It’s Not Crypto)

Our columnist connects the dots between SPACs, NFTs, Paul Ryan, Emily Ratajkowski, and, of course, New Jersey’s Hometown Deli.

Our columnist connects the dots between SPACs, NFTs, Paul Ryan, Emily Ratajkowski, and, of course, New Jersey’s Hometown Deli.

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, checking the thermometer inside and outside the art market…

Over the past week, events in the art and finance markets underscored that buyers are only intensifying their interest in speculative assets as rich countries like the U.S. approach full reopening. The similar heat waves gathering in these adjacent economic sectors indicate where the art trade is heading in the coming months—and why market participants should be extra careful not to lose themselves in the swelter ahead.

Let’s start with a standout feature of spring auction week’s New York return. Premier works by several time-honored artists were instrumental in sending Christie’s and Sotheby’s surging north of a combined $1.5 billion in evening and day sales, but so too was a slew of fiercely contested pieces from ascendant talents. In fact, almost all of the most in-demand artists were ‘80s babies. (All sales figures include premiums unless otherwise noted; presale estimates do not.)

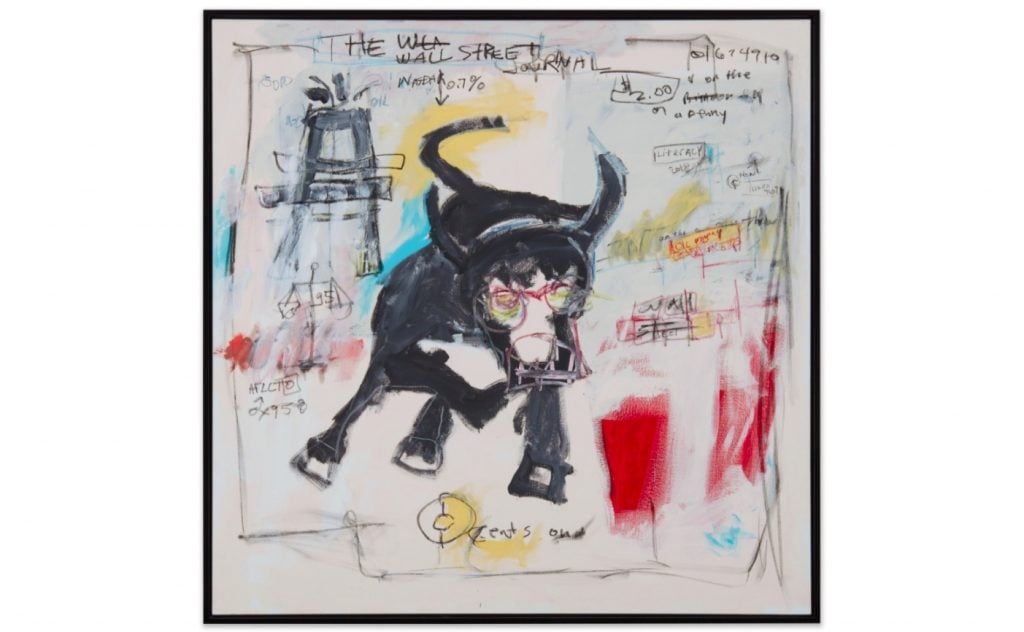

Salman Toor, The Servant (2013). Photo courtesy Christie’s.

Christie’s and Sotheby’s respective evening sales set four personal records for artists under age 40: Nina Chanel Abney ($990,000), Salman Toor ($867,000), Jordan Casteel ($687,500), and Alex da Corte ($187,500). The day sales built at least three more new pinnacles for members of this demo, as my colleague Nate Freeman noted. A Claire Tabouret canvas peaked at $870,000, nearly triple the high estimate; a rare Issy Wood reached $201,600, about 2.5x more than the house’s most optimistic projection; and a Jammie Holmes nude barely missed tripling up its high estimate, landing at $175,000.

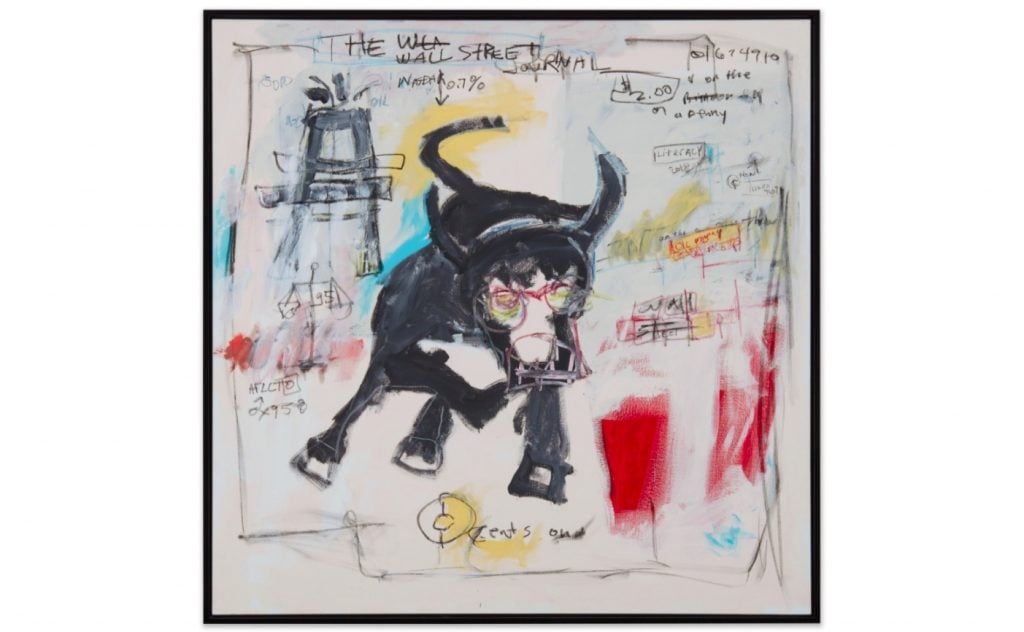

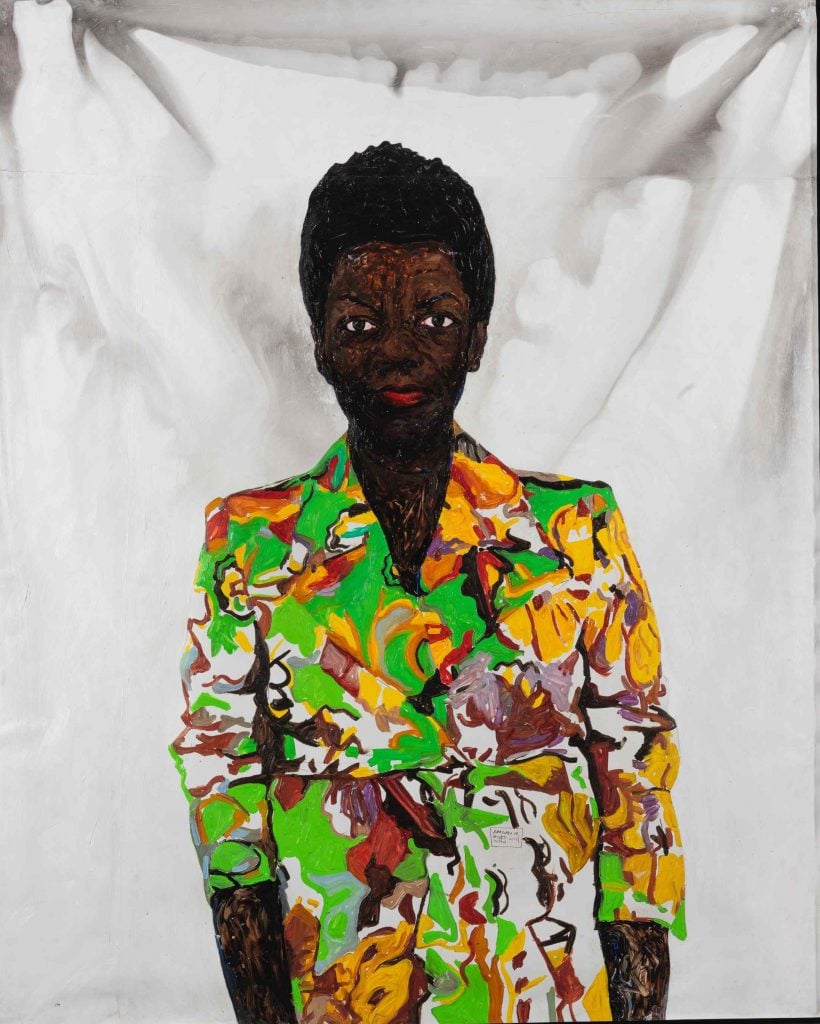

Focusing exclusively on shattered records also obscures the fact that buyers chased hard after multiple lots by the millennials above, as well as their sought-after peers. A trio of paintings by Toor all went for more than three times their presale ceiling in Christie’s day sale. Another Holmes painting (this time of the Wall Street Bull) doubled its high estimate at Sotheby’s. When the smoke cleared, Amoako Boafo’s portrait of Studio Museum director Thelma Golden changed hands at just under $479,000 despite a top expectation of $350,000. Two paintings by the late Matthew Wong both blitzed through expectations, with In Dreams (2016) finding a buyer at $189,000, almost quintupling its high estimate.

Amoako Boafo, Thelma in Colored Blazer (2018). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The point is bidders are once again plunging into trench warfare with one another for the right to pay multiples of the primary-market price for works by the most sought-after young artists in the game. Their behavior also tracks with what investors have been up to lately in another realm of high-variance speculation.

If you’ve never before heard of a special purpose acquisition company (known as a SPAC, pronounced like it rhymes with “jack”) you’re not alone… but you’re in a smaller crowd than you would have been a year or two ago. Andrew Ross Sorkin of New York Times DealBook fame called SPACs “the biggest thing in financial markets of the moment” this February—yes, even amid NFT-mania—and their influence among investors has only grown in the time since.

Beyond leaving their imprint on general wealth-pursuit strategies, however, a handful of recent SPAC-related developments typifies the magnitude of the speculative moment we’ve entered. In that sense, they might just be the alarm screaming loudest about the mounting pressure to overpay for upside opportunities across every market right now—including art.

For the uninitiated, I’m going to hand off the task of summing up SPACs to Bloomberg’s Matt Levine via the May 12 edition of his “Money Stuff” newsletter:

The basic way a special purpose acquisition company works is that a sponsor raises a pool of money and has two years to find a company to take public. If the sponsor finds a company, signs up a deal and gets the SPAC’s shareholders to approve it, the sponsor gets rich—typically the sponsor gets shares in the newly public target company worth 20% of the amount raised. If the sponsor does not do a deal within two years, though, the SPAC’s shareholders get their money back, and the sponsor gets nothing and has to foot the bill for the SPAC’s startup and administrative costs.

This is why SPACs are sometimes referred to as “blank-check companies.” By buying into a public SPAC, investors also give its sponsor the autonomy to pursue whatever private companies the sponsor wants with no oversight—or at least, no oversight until the potential merger has been hammered out between would-be corporate partners. SPAC shareholders get an actual vote at that point, as well as retaining the option to simply sell their SPAC stake back on the market if they think the proposed endgame of the SPAC is trash.

(If you haven’t figured it out by now, everyone talking about SPACs loves to say the word “SPAC” as much as humanly possible. Try it now. Kind of delightful, right? I half-believe that the jargon accounts for at least 15 percent of the cash now sloshing around SPACs, especially when you factor in the opportunity to use even more amusing adjacencies like “SPAC-off”—that is, a bidding war between two SPACs courting the same company.)

Investment in the SPAC space has grown so hot and humid over the past several months that it makes the NFT market feel like a climate-controlled museum vault. Consider that NFT sales during the first quarter of 2021 totaled about $2 billion across major exchange platforms, according to a report from blockchain gaming and collectibles database Nonfungible.com. For argument’s sake, let’s add another billion on top of that to give the benefit of the doubt to some significant platforms (primarily NBA Top Shot, Nifty Gateway, and Rarible) that Nonfungible excluded from its report due to implied suspicions over the integrity of their transaction data.

Rounding up like that might not even be especially aggressive, since NBA Top Shot and Rarible have combined to ring up about $672 million in lifetime NFT sales per crypto-analytics site DappRadar.com. In the end, though, it kinda doesn’t matter once you push SPACs onto the scale: By mid-March 2021, investments in SPACs had soared to just shy of $88 billion, according to SPAC Research.

Another way of saying it: Even the most generous appraisal of the NFT trade in Q1 still gives its investor base about 30X less buying power than the investor base for SPACs. Which raises the obvious question: What’s the appeal? And it turns out the answer ties us right back to the art and collectibles market.

SPAC sponsors are sometimes seasoned investors and entrepreneurs whose business acumen could mean something major for investors’ potential returns. (Mega-collector Michael Ovitz and finance goliath Bill Ackman co-sponsor one, for instance.) But many others are fronted by celebrities with… let’s say “highly variable” business credentials. They include superstar athletes (Shaquille O’Neal, Serena Williams, Colin Kaepernick), pop music figures (Jay Z, Ciara, Sammy Hagar), and even career politicians such as former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

Paul Ryan attends the game on January 11, 2020, at M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore, MD. (Photo by Mark Goldman/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

If some of those names sound a lot like the types you’ve heard cashing in by issuing their own NFTs this year, your pattern-recognition skills are on point. Recall the recent crypto-collectible debuts of Snoop Dogg, Paris Hilton, William Shatner, and NFL tight end Rob Gronkowski.

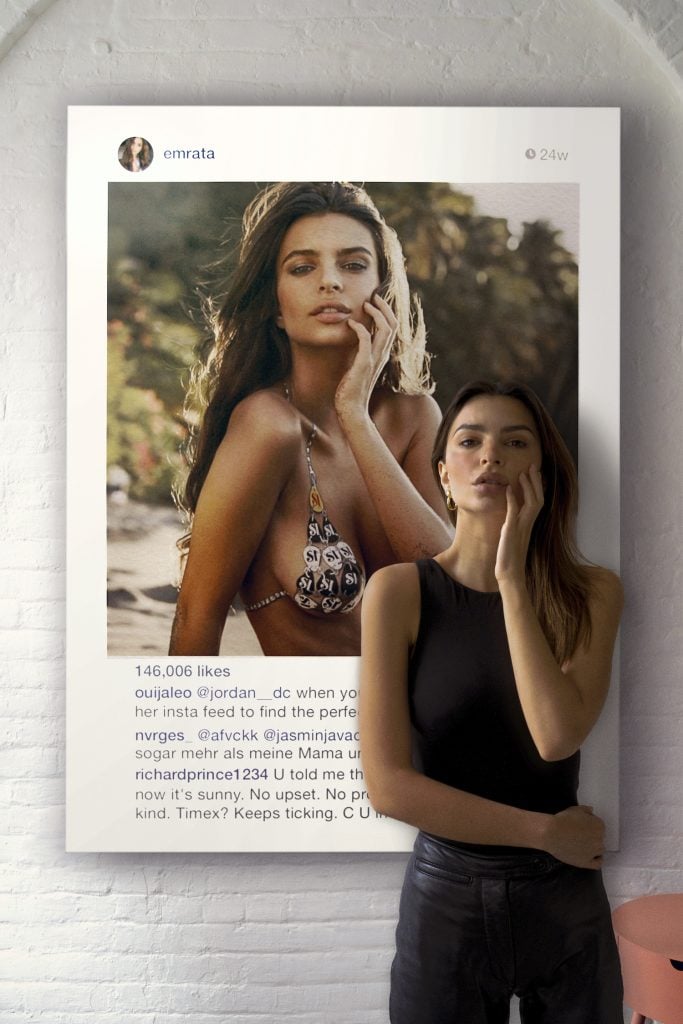

Which leads us back to auction week, believe it or not. Among the explosive results for sought-after millennial artists, Christie’s also notched a big win for an NFT by model and collector Emily Ratajkowski, whose backstory-rich token brought $175,000 after being offered with no estimate in the house’s day sale. But were bidders spurred on more by the perceived long-term value of the underlying digital asset, or by the allure of Ratajkowski’s pop-cultural aura in an overheating market enabled by a historically askew economy?

Celebrity SPAC sponsors invite a similar question: Are most, or even many, of the investors cramming billions of dollars into these vehicles like clowns into tiny circus cars making a sober fiscal decision? Or are they getting sucked in to dumb-money deals by the gravitational pull of the stars at their centers, whatever universe those stars occupy?

Emily Ratajkowski’s NFT. Photo courtesy of Emily Ratajkowski and Christie’s Images Ltd 2021.

As ever, the answers lie somewhere on a long spectrum rather than on one side or the other of a hard binary. But whether the investment (or “investment”) target is a SPAC, a celebrity NFT, or a hotly pursued work by an ascendant young artist, the ferocity of the chase and the velocity of the resulting prices are driven by already-rich people who got much richer during the shutdown, accidental millionaires who lucked up on crypto or meme stocks, or regular Joes/Janes/Jesses putting stimulus money into what they hope will be high-upside, quick-return alternative trades.

Yet the SPAC news cycle has given us the most glaring reasons to think carefully about how much some of these opportunities are worth flying after—and when it’s time to eject from the cockpit.

As you may have noticed in Levine’s explanation of SPACs, there’s often a troubling spread between their sponsors’ incentives and their investors’ interests. Sorkin noted in a more recent column that most blank-check firms only prevent sponsors from liquidating their 20 percent ownership stake for a year after the merger closes, and “many include a trapdoor” allowing sponsors to cash out early if the post-deal share price of the SPAC stays more than 20 percent above its initial share price for 20 days out of any 30 consecutive days.

That might sound like a low-probability trigger… until you find out that most SPAC shares start their life trading at $10, meaning that if they top $12 for 20 days, many sponsors can grab the bag and GTFO. Sorkin also backed up fears about the divergence in incentives with data, writing that “in a review of hundreds of deals, many sponsors of SPACs appear to be planning to rush for the exits from the outset, and they rarely invest much of their own money in the first place.”

This curious arrangement has generally worked out much better for SPAC sponsors than SPAC investors. According to JPMorgan Chase, sponsors made an average return of 648 percent on their stakes between early 2019 and early 2021, often by flipping quickly. But shareholders who invested in the same SPACs after they executed their mergers, then held on, made an average return of only 44 percent—worse than the upside of buying into a standard index fund tracking, say, the S&P 500.

Redbox movie rentals in Simi Valley, California. (Image courtesy Getty Images.)

The (possible) upside and (more likely) downside were both on view in recent days. DealBook broke news this Monday that a SPAC called Seaport Global Acquisition Co. is preparing to ally with Redbox, the once-ubiquitous DVD kiosk business, at a $693 million valuation. Which could be a brilliant wager on a post-shutdown bounceback for customers hesitant about streaming… or a disastrous bet on an increasingly niche entertainment sector hurtling into a death spiral.

Over the weekend, Bloomberg also reported that five electric-vehicle startups (an especially hot target sector for SPACs) have collectively shed about two-thirds ($40 billion) of their peak market value since going public via different blank-check companies.

And if none of that makes you wary of the froth content in the speculative finance market, let me close by noting Friday’s executive shake-up at New Jersey’s Hometown Deli, the unassuming sandwich shop that stymied investment analysts for weeks by pairing $40,000 in sales since 2019 with a mysterious $100 million valuation (not a misprint!) and institutional shareholders including Duke and Vanderbilt universities. The puzzle was finally solved in late April, when FT‘s Mark Vandevelde learned Hometown’s holding company is actually… a pseudo-SPAC designed to shuttle an Asian company onto a U.S. stock exchange ASAP.

To be clear, I’m not saying that winning a Salman Toor at auction last week is identical to buying shares in a Garden State deli sliding through an SEC loophole. But I am saying that market participants are showing all kinds of signs that they’re chasing returns at full throttle. No matter who you are, it’s worth asking how that race affects your own behavior on the road ahead.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Sometimes you get to ride the bull market to glory, but eventually you’ll just get the horns.