The Gray Market

Why Better Artist Resale Royalties Are an Opportunity for Better Business in the Art Market (and Other Insights)

Our columnist explains why it hurts almost all market players to portray resale royalties as a zero-sum game.

Our columnist explains why it hurts almost all market players to portray resale royalties as a zero-sum game.

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, another look at the landscape of incentives…

There is a small group of subjects in the art business with the power to drive opposing parties to the ramparts with surprising ferocity. Among them is an artist resale right (ARR)—the official term for the royalty payout an artist might get when their work changes hands on the secondary market. The new ups and downs of the concept were back in the news cycle last week thanks to a solid survey from John Gapper in the Financial Times.

Based on his reporting and my own conversations, my takeaway is this: While recent advances in technology have brought resale royalties to wider prominence than ever (especially in the U.S.), it’s unlikely that technology will have enough muscle to overturn the status quo on its own. But if the technology can be synthesized with a more holistic argument about an ARR’s value to all sides of the transaction, there is a real chance to change the resale royalties game for good.

To review, different geographical regions and individual nations take vastly different approaches to an artist resale right. For resales made by commercial professionals in the U.K. and much of the European Economic Area, the royalty for artists (who must also be nationals of one of those same countries) is determined as a percentage of any resale of at least €1,000 (or its Sterling equivalent). But the payout is also capped at €12,500 (currently about $12,600), even if the work became the most expensive ever sold.

ARR has no legal mechanism at all in the U.S. The last remaining prospect for it collapsed in 2018, when a federal appeals court rejected the 1977 California Resale Royalty Act. The bill would have compelled professional resellers to carve off a portion of their secondary-market sales proceeds for unique works if they themselves and/or the transaction were based in the Golden State. Instead, its detonation left the world’s largest art market as either a wasteland for artist royalties—or, more optimistically, a blank slate.

As sought-after interdisciplinary artist Hank Willis Thomas told the New York Times, visual artists in the U.S. are among the only artists in any medium who still receive no royalties or residuals from downstream consumption of their intellectual property. Musicians, screen actors, film directors, T.V. showrunners, screenwriters, authors: all directly benefit if their I.P. succeeds in a secondary transaction. The parameters by which this happens differ, but every field gets to it somehow. In my view, most of what separates visual artists from these near-peers is a history of being excluded by the status quo (despite their best efforts).

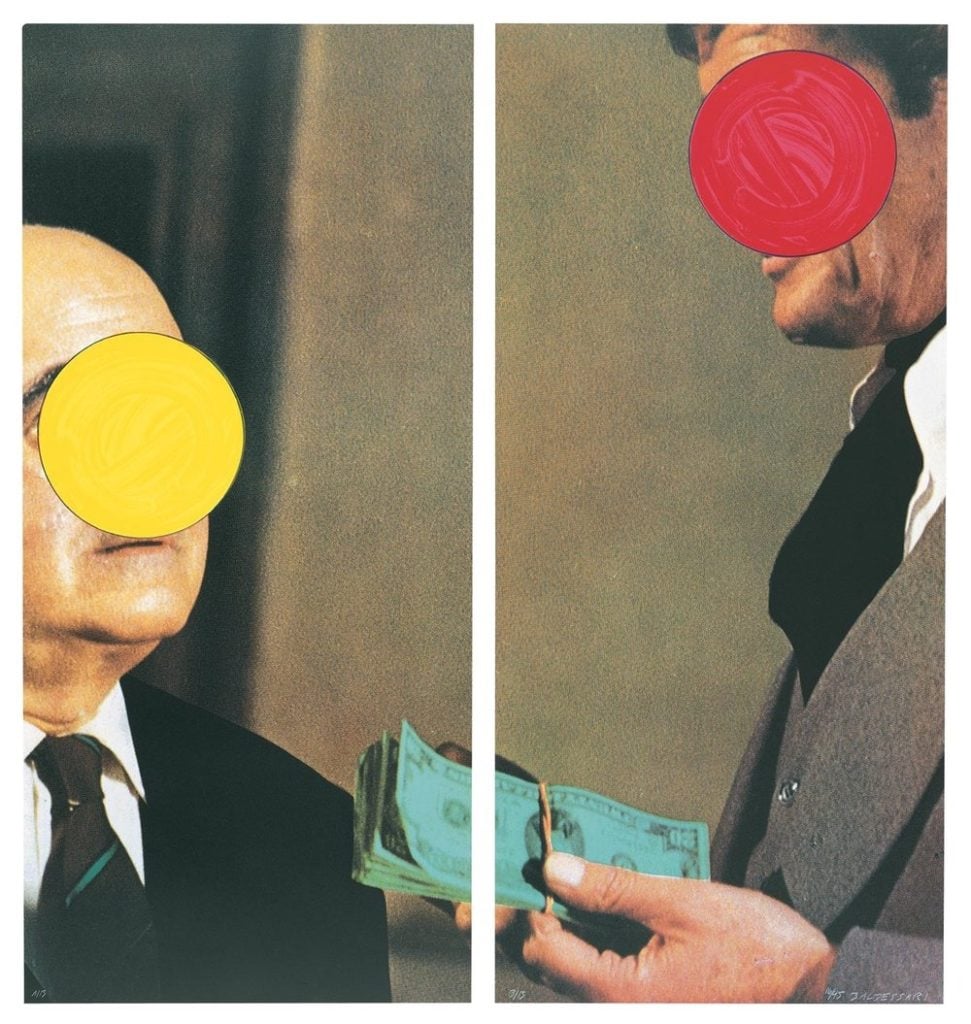

Mock-up draft of the Artist’s Contract in English (ca. 1971). Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

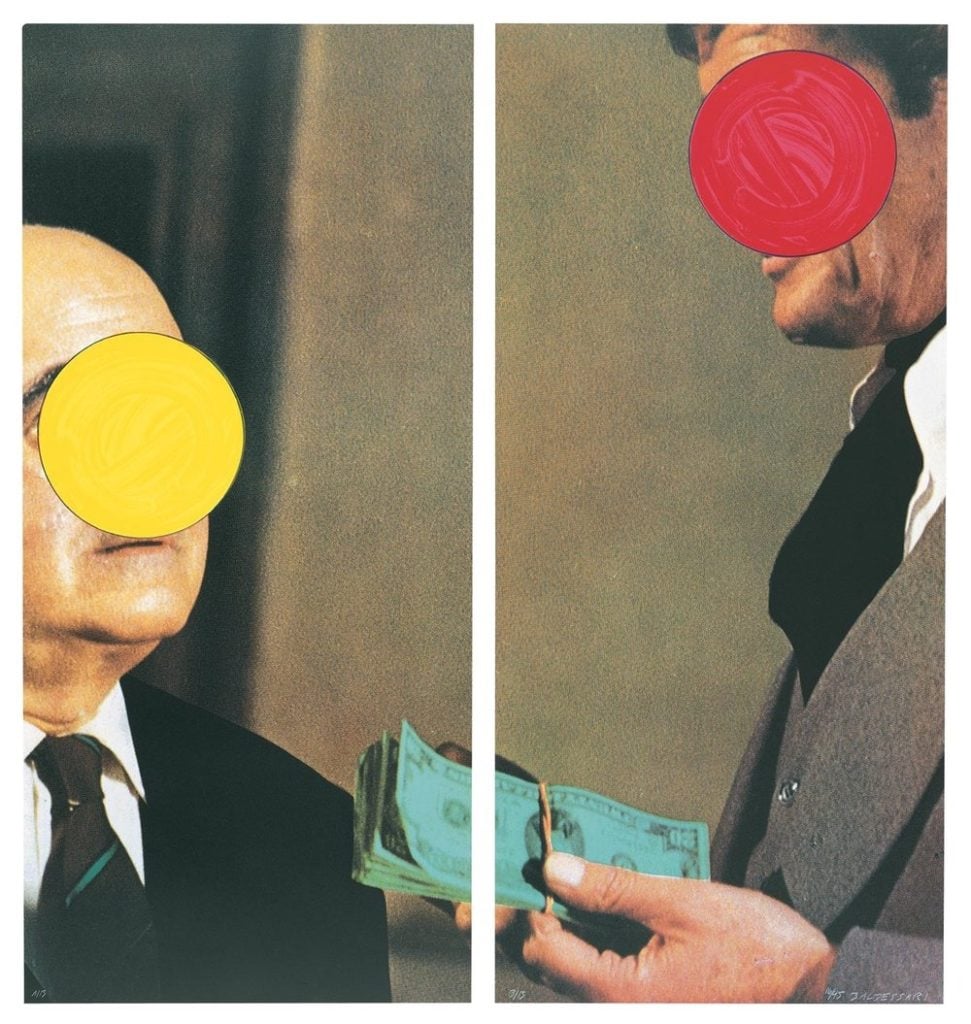

In my cannonball run through press and literature on ARR, I was struck over and over again by the zero-sum thinking that has long dominated conversation on the subject. The source of this tension is obvious. By definition, if U.S. artists were to start receiving a cut of resale proceeds on their work, that cut would have to come out of the pockets of the reseller and/or an intermediary, who together would no longer be hoovering up the net profits they have grown accustomed to.

When it comes to implementing resale royalties in the U.S. art market, however, it’s important to recognize that the problem has become almost entirely theoretical. Worse, many, if not most, of the theories and behavioral models being used to justify the status quo lean heavily on twin pillars: conventional wisdom about human behavior, and earlier market conditions that have shifted significantly in the four years since the California Resale Royalty Act met its judicial demise. The only way to map out useful next steps on an American ARR is to update our priors on both fronts.

Let’s start with the conventional wisdom. Almost no one in any walk of life reacts well when you suddenly take away what time and tradition have taught them is rightfully theirs, so it’s fair to anticipate that resellers in the U.S. (particularly the major auction houses) would be dead set against losing part of their revenue to royalty payments. There is at least some hard evidence to back up this notion, too. Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and eBay were the defendants in the lawsuit that ultimately doomed the California Resale Royalty Act; disclosure forms from 2018 through 2021 also indicate that among the issues that Sotheby’s paid lobbyists to address on its behalf was the American Royalties Too Act, which would have enshrined a nationwide resale royalty to artists on works sold under the hammer.

But most of the above happened before the crypto boom. More than a year and several billion dollars in transactions later, resale royalties are indeed an integral component of an NFT market that has attracted widespread attention (and more than a little participation) from buyers and sellers in the art establishment. Whether an artwork was born digital, physical, or somewhere in between, my recent conversations lead me to believe that experiences with crypto art have meaningfully shifted norms and expectations about ARR in general.

Amy Whitaker, associate professor at New York University and co-author (with Nora Burnett Abrams) of the forthcoming book The Story of NFTs: Art, Technology, Democracy, is among those who argue the industry has reached a “fulcrum moment” on resale royalties. “It makes sense structurally for artists to maintain an interest in part of the value that they create,” she said. The convergence of new technology and market experience has just clarified the logic.

Even some decision-makers at the Big Three auction houses are reconsidering the issue. “Through NFTs, auction houses have started to understand that collectors’ resistance level is not what they once thought it was,” said Max Kendrick, cofounder of Fairchain, a platform that uses blockchain-backed records to authenticate, track title to, and facilitate the sales of tangible works that include an embedded resale royalty of up to 10 percent. “There is a silent majority of collectors who support artists and their right to a resale royalty.”

Beyond what those like Kendrick and Whitaker (who is a Fairchain investor) perceive as a soft proof of concept in NFTs, multiple factors play a role here. One is generational change among buyers. Just as younger collectors tend to prefer different artists than their older counterparts, so too do they tend to think differently about how the art market should work. Education is key across generations, as well. To date, Kendrick estimates that 90 to 95 percent of collectors sign onto Fairchain’s pitch “without asking any further questions” once they review agreement terms.

“From our pilot sales through today, the biggest impediment isn’t what collectors think,” he said. “It’s what other people think collectors think.”

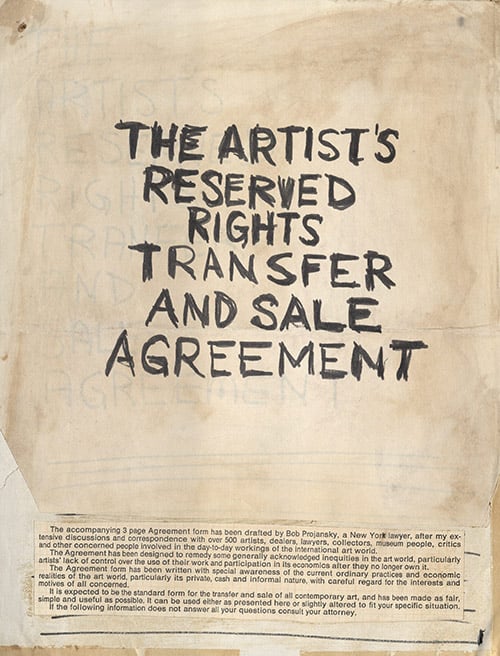

Portrait of art collectors Robert and Ethel Scull as they pose with artists George Segal, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist, at the Scull’s home, November 1973. Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

Crucially, the motivations are bigger than just resale royalties. In a well designed system, royalties reflect a broader alignment of incentives among artists, dealers, and collectors.

For a collector to one day benefit from a resale, an artist has to continue to produce compelling work, network with other influential figures in the field, tune out the various demons that could knock them disastrously off track, and much more. The collector and dealer have vital contributions to make, too, from promoting the artist within their circles, to loaning works and/or donating money for prestigious institutional exhibitions, to building collections or programs that will buoy the artist by association.

To return to the example of Fairchain, Kendrick said he explains his business to collectors as a holistic cooperative vision. The resale royalty in a work’s digital contract is much more than a gesture of equity. The collector gains something for agreeing to pay it: a blockchain-backed certificate that ensures the work will stay connected to the artist who created it, meaning a permanent guarantee of its authenticity, provenance, and inclusion in an eventual catalogue raisonné. Which also means that if and when the buyer chooses to resell the work, the royalty they’re paying to the artist doubles as a kind of one-time protection fee to maximize its market value by eliminating some of the core uncertainties that plague auction houses, secondary-market dealers, and their clients.

Fairchain is hardly alone in this general effort. Outside the crypto space, the past few years in particular have seen a surge in initiatives led by artists, galleries, and foundations that frame resale royalties as good business and good policy for all involved. From Gagosian agreeing to donate the sale proceeds of a Titus Kaphar painting to Kaphar’s NXTHVN community-art platform last year, to curator Destinee Ross-Sutton requiring buyers of the works in Christie’s “Say It Loud” sale in 2020 honor an updated version of the Seth Siegelaub–Robert Projansky Artist’s Contract, to the nascent Resale Royalty Awards Program launched by the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, more and more players of note in the art trade are making equitable redistribution a part of a successful market strategy.

These examples illustrate why it is misguided at best to frame ARR primarily in terms of zero-sum payouts. There is an unbridgeable gulf between a buyer who can recognize that acquiring an artwork by a living artist opens what could be a mutually beneficial partnership with tangible and intangible rewards, and a buyer whose primary concern when acquiring an artwork by a living artist is whether they will have a clear path to 100 percent of the net profit on its resale. Of course the latter would resist the prospect of paying 10 percent of its auction price to the creator! But it’s likelier to me that these clients make up a loud, aggressive minority of collector-dealers rather than the vast majority of art buyers.

It’s also why it’s important to watch the entire storied face-off between a young Robert Rauschenberg and collector Robert Scull. After Scull successfully resold the artist’s Thaw (1958) at auction for $85,000 roughly 15 years after acquiring it for a mere $900, a livid Rauschenberg famously accused Scull of profiting unduly off of his creative labor. While summaries of the episode tend to reduce it to an instance of a righteously aggrieved artist speaking truth to power, the tape tells a more complex tale.

Scull rightly points out to Rauschenberg after his outburst that the record auction result will only boost the artist’ primary-market prices going forward, saying, “I’ve been working for you, too. We work for each other.” (You can find the clip online here. The Scull-Rauschenberg episode begins at 27:11 and lasts less than a minute.) Rauschenberg then invites Scull to come to his studio and buy his new work, albeit with the half-jab that Scull should do it “at these prices.” Then, they hug and go their separate ways.

It would be going too far to assume that Rauschenberg fully forgave Scull, but there’s a deeper truth to the frenemy energy that crackled between them in that auction room nearly 50 years ago. The actions of artists, collectors, and dealers have always radiated back onto each other in ways that affected everyone’s individual fortunes. Resale profits are only one thread in that shared network, but they are an important one.

In the ongoing absence of ARR legislation, then, the U.S. could be a laboratory for private-sector initiatives that use resale royalties as one lever to more closely align all parties’ interests. (Those that succeed could even be codified or buttressed by laws later.)

“The larger idea around artist resale royalties is that they are about centering artists in art markets, up to and including all of us having the mindset of artists to try out imperfect solutions… rather than waiting around to give one perfect solution a gold star,” Whitaker said.

If crypto has done nothing else of value, it has at least cracked the door to this possibility. But it will take more than appeals to fairness to convince a critical mass of market actors to walk through and start iterating.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: as a brash young Wayne Gretzky said, you miss 100 percent of the shots you don’t take.